The Gulag: Communism’s Penal Colonies Revisited

Daniel W. Michaels is a Columbia University graduate (Phi Beta Kappa, 1954) and a Fulbright exchange student to Germany (1957). Now retired after 40 years of service with the U.S. Department of Defense, he writes from his home in Washington, DC.

During the twentieth century it became common practice for nations to detain citizens whose loyalty to the state was considered unreliable or suspect in times of war or “national emergency.” To sequester such persons Britain, the United States, and Germany all established centers, variously called (often depending on who won and who lost) relocation centers, detention centers, labor camps, concentration camps, or death camps. Depending on circumstances, the treatment of inmates varied from benign to cruel. Such facilities in these countries were, however, temporary measures undertaken during times of national peril. Only in the Soviet Union, where such camps were collectively known as the Gulag (an acronym in Russian for the Main Directorate of Corrective Labor Camps and Colonies), were they a permanent and integral part of the government.

Beginning in the 1970s, British researcher Robert Conquest and Russian Nobel laureate (and former Gulag detainee) Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn did much to alert the world to the horrors of the USSR’s vast penal empire. Conquest’s readership has been limited largely to historians and the better educated, while today Solzhenitsyn’s monumental Gulag Archipelago is scarcely read at all, except in a condensed version. Over the past decade, however, their pioneer work has been supported and elaborated on by serious studies compiled by survivors of the Soviet camps and by Russian, French, and German scholars. The most important of these (and the basis for this essay) are: The Gulag Handbook by Jacques Rossi; Sistema ispraviltel’no-trudovykh lagerey v SSSR. 1923–1960 (The System of Corrective Labor Camps in the USSR, 1923–1960), by a team of Russian researchers; Ralf Stettner’s recent study of the Gulag under Stalin; former Gulag administrator D.S. Baldaev’s Gulag Zeichnungen (Sketches from the Gulag); Avraham Shifrin’s somewhat older Guidebook to Prisons and Concentration Camps of the Soviet Union; and the powerful Black Book of Communism, by Stéphane Courtois.[1]

For whatever reason, American researchers have seemed content to relegate the “Gulag archipelago” to the dustbin of history. Pitifully for the reputation of the United States and Great Britain, all too many of their scholars, writers, artists, and politicians ignored, or even sought to justify, the Soviet camps when Communism ruled Russia. Their infrequent condemnation of the Soviet penal system was all too often on behalf of Communists who had fallen from favor. In 1944 Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s vice president, Henry Wallace, visited one of the worst and most brutal of the Soviet penal camps, Magadan, lauding its sadistic commander, Ivan Nikishov, and describing Magadan as “idyllic.”

The effects of confinement at hard labor, with its poor diet, exposure to the elements, and abuse by guards, are clearly evident in this picture of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn taken at a Gulag camp in 1946. He would spend seven more years in the camps, and three additional years of internal exile. Solzhenitsyn's later writings on the Gulag, including the fictional “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” and “The First Circle” and the literary-historiographical “Gulag Archipelago,” helped him win the Nobel Prize in 1970 and four years later resulted in his expulsion from the Soviet Union. In 1994, after the collapse of the Communist regime, Solzhenitsyn returned to Russia.

Workings of the Gulag

Organizationally the Gulag was subordinated to the secret police entity of the day (successively, Cheka, GPU, OGPU, NKVD, MVD, and KGB, from the last of which emanate many of the leaders of today’s Russian Federation). The founder of the Soviet secret police, Feliks Dzerzhinsky, expressed the guiding principle of the Cheka in 1918: “We represent in ourselves organized terror – this must be said very clearly.” All subsequent Soviet governments have rigorously observed that principle. In one consequence of that rigor, conditions in the camps of Communist Russia were typically far more brutal than those of the dreaded Siberian exile under the Tsars.

If France had one notorious penal colony – Devil’s Island – the Soviet Union had hundreds. Of several thousand work camps of various types, more than five hundred were officially ITL (for “ispravitel’no-trudovoy lager”), corrective labor camps and penal colonies. The first of these was established in 1917; eventually the ITL camps extended across the breadth of the USSR, from the severe arctic conditions of the far north to the scorched plains of Central Asia. Or, as Solzhenitsyn put it: “from the Cold Pole at Oy-Myakon to the copper mines of Dzhezkazgan.”

Since the camp system was essential to the Soviet economy, the inmates were put to work in every aspect of hard labor – in railroad construction, road building, canal building, forestry, mining, agriculture, construction sites, etc., under conditions that were usually inhuman and unhealthy, and oftentimes deadly. Women, though housed in separate barracks, often shared the same work camps as the men – and worked side by side with them at the same labor. There were special camps for children, for mothers with babies, and other exceptional cases. Psychiatric wards (psikhbol’nitsy) “treated” other intractable “enemies of the people.”

In 1943, with the “Great Patriotic War” raging, the Communists introduced an even severer category of labor camp, the “katorga” (hard labor camp), within the ITL system. Prisoners assigned to a katorga were assigned the hardest work and received the lowest rations and the least medical attention. (The word “katorga” stems from in Tsarist times, when hard labor, along with “ssylka,” or Siberian exile, were standard, though much milder, punishments.)

As was the practice in the Soviet civilian sector in general, and long predating the German use of similar slogans in their concentration camps, the importance and joys of work were proclaimed and extolled by countless slogans posted in the camps: “Work is a matter of honor, fame, courage, and heroism”; “Shock work is the fastest way to freedom”; or, more ominously, “No work, no food.”

The basic daily food ration (the “payka”) ranged from 400 to 800 grams of bread, which accounted for more than half the prisoner’s daily calories (1200–1300). This amount varied, depending on whether the prisoner was a shock worker or a Stakhanovite, an invalid, in isolation, etc. The most productive workers received a food bonus of fish, potatoes, porridge, or vegetables to supplement his bread. (Coincidentally, the American Morgenthau Plan for occupied Germany called for the allotment of about the same number of calories [1300] a day per German.) The UN World Health Organization sets the minimum requirements for heavy labor at from 3100–3900 calories per day.

Little known today, Naftali Frenkel, like Solzhenitsyn, was a prisoner in a Soviet penal camp. While an inmate, however, the one-time Jewish timber magnate devised a system of labor exploitation that led to the deaths of millions of prisoners in Soviet penal camps, and earned him a life of ease as a high-ranking officer in the NKVD. Solzhenitsyn wrote of Frenkel in “The Gulag Archipelago: Two”: “have the feeling that he really hated this country!”

The inmate population reflected a cross-section of the USSR: Christian and Muslim clergymen, “kulaks” (or independent farmers), political dissidents, common criminals, “economic criminals,” the remnants of the old elite, Communists who had fallen from favor, ethnic minorities, the homeless, “unpersons,” “hooligans,” and persons who had been, once too often, tardy at work.

Within the camps of the Gulag, inmate society came to be broken down into categories that depended on the prisoner’s particular crime. Most political prisoners or counterrevolutionaries were referred to as “58ers” for having violated Article 58 of the criminal code; common criminals were called “urki” or “blatnyaki”; less violent criminals accused of violating some aspect of the civil code were categorized as “bytoviki”; individuals accused of undermining Soviet economic laws were referred to as subversives or pests – “vrediteli” in Russian; trustees or “pridurki” in the camps, those most likely to survive their imprisonment, acted as camp service personnel. All inmates were referred to as “zeki,” the acronym for the Russian word for prisoner.

Reform, Soviet Style

Of all those who helped devise and perfect the slave labor system of the Gulag, special mention must be made of Naftaly Aronovich Frenkel. Frenkel, a Jew born in Turkey in 1883, had been a prosperous merchant there, but after the Bolshevik revolution he moved – as did an appreciable number of Jews – to the Soviet Union. Based in Odessa as an agent of the State Political Administration, Frenkel was responsible for the acquisition and confiscation of gold from the wealthier classes. The unscrupulous Frenkel was unable to resist this temptation, however, and in 1927 was arrested, on orders of the Moscow central office, for skimming off too much gold for himself. Convicted of economic crimes, he was sent to the Solovetsky Special Purpose Camp (or SLON, as it was designated by the Soviet bureaucracy), a bleak Arctic penal colony. Frenkel’s special talent for improving inmate work efficiency was quickly noticed by the camp officials there, and it was not long before he was ordered to explain his ideas and methods to Stalin personally. His main proposal was to link a prisoner’s food ration, especially hot food, to his production, essentially substituting hunger for the knout as the main work incentive. Frenkel had also observed that a prisoner’s most productive work is usually done in the first three months of his captivity, after which he or she was in so debilitated a state that the output of the inmate population could be kept high only by removing (killing off) the exhausted prisoners and replacing them with fresh inmates. Another method of stimulating enthusiasm for work among prisoners – and at the same time culling the camp population by killing off the weak – was quite simple. When the prisoners were called out on a work detail, they fell into line. The last man in to line up would be shot as a laggard (“dokhodyaga”), one weakened enough to be useless for work. These policies would ensure a constant inflow of new prisoners, providing fresh labor while weeding out opposition to Stalin and his party.

So pleased was Stalin with Frenkel’s ideas on the efficient exploitation of inmate labor that he made him construction chief of the White Sea Canal project, and later of the BAM railroad project. In 1937 Stalin appointed Frenkel head of the newly founded Main Administration of Railroad Construction Camps (GULZhDS). In that capacity, Frenkel was called upon to provide railroad transport facilities to the Red Army in the 1939–40 “Winter War” against Finland, and for the duration of Soviet participation in the Second World War. He was eventually awarded the Order of Lenin three times, named a Hero of Socialist Labor, and promoted to the rank of general in the NKVD.

The methods instituted by Frenkel in building the White Sea-Baltic Sea Canal became the standard operating procedures for most subsequent labor camps, including the BAM (Baltic-Amur Magistral) railroad project, the Dalstroy (Far East Construction), Vorkuta, Kolyma, Magadan, and countless other hell holes. Working on the BAM project after the war, the inmates noted that many of the rails were marked “made in Canada” – a reminder of the aid given by the Western powers to support the Soviet war effort.

Welcome Guests

The number of inmates varied over time. Thus, for example, there were roughly 300,000 prisoners in Soviet labor camps as early as 1932, a million in 1935, and two million by 1940. (President Roosevelt officially recognized the Soviet Union in 1933, extending the hand of friendship to its leader just as Stalin was starving and imprisoning millions of his subjects in Ukraine and Russia.) During the war, Stalin displayed his own brand of clemency by permitting some one million inmates to serve in various Red Army penal units. These were employed in clearing out minefields, not infrequently by walking through them at gunpoint, and in other hazardous tasks. Nevertheless, the population of the Soviet concentration camp system rose precipitously in 1945–46.

From 1939 on, the Gulag filled up with nationals from the USSR’s enemies: Finns, Poles, Germans, Italians, Romanians, and Japanese, many of whom were held for years after 1945. Although, technically, German prisoners of war were under the jurisdiction of GUPVI (Main Directorate for POW and Internee Affairs), they were nonetheless used no differently than other Gulag inmates. Indeed, in the first few years of the war the death rate for POWs exceeded that for non-POWs in the camps. Comparatively few German were taken alive before Stalingrad.Most were shot out of hand, many of them mutilated. Of the 95,000 German POWs captured at Stalingrad, only 5,000 survived to return home. Of the dead, some forty thousand did not survive the march from Stalingrad to the Beketovka camp, where 42,000 more perished of hunger and disease. Particularly murderous treatment was inflicted on SS POWs, many of whom, along with remnants of the Vlasov forces, were imprisoned and died on Wrangel Island.

By the war’s end, the USSR held 3.4 million German soldiers prisoner. Under the provisions of the Yalta Agreement, the U.S. and U.K. had agreed to the use of German POWs in the Soviet Gulag as “reparations-in-kind.” Thus, rather than repatriate them to their homeland, Stalin began incorporating this captive human booty into the work camps in the summer of 1945. Recognizing that the German prisoners of war were productive workers, Stalin ordered that they be given food rations proportionate to their work. The ration included 600 grams of black bread every day, spaghetti, a little meat, sugar, vegetables, and rice. Officers got somewhat more, while, naturally, Axis “war criminals” got less. Nonetheless, between 1941 and 1952, almost a million German POWs died in the camps. The last of the surviving POWs (10,000 men) were released from the Soviet Union in 1955, after a decade of forced labor. Approximately 1.5 million German soldiers from the Second World War are still listed as missing in action. Of an additional 875,000 German civilians abducted and transported to the camps, almost half perished.

When the war ended in May 1945, British and U.S. civilian authorities ordered their military forces in Germany to deliver to the Communists great numbers of former residents of the USSR, including men who had taken up arms with the Germans against the Soviets, prisoners of war, forced and voluntary workers in the German wartime economy, and numerous persons who had left Russia and established different citizenship many years before. This “repatriation” of 4.2 million ethnic Russians and 1.6 million Russian POWs from defeated Germany was augmented, as noted above, by a great influx of German POWs and the arrival of large numbers of civilians abducted or deported from Germany and Eastern Europe. Tens of thousands of Lithuanians, Latvians, and Estonians were deported to Soviet camps, to be replaced in their homelands by Soviet settlers. While most repatriated ethnic Russian civilians, chiefly the women and children, were eventually reincorporated into Soviet life, the Russian POWs and the Vlasov men were put under the jurisdiction of SMERSH (Death to Spies), which sentenced about a third of a million to serve from ten to twenty years in the Gulag. In 1947, swollen by the dictates of Yalta and by Operation Keelhaul, the total number of Gulag prisoners hit its peak at about nine million.

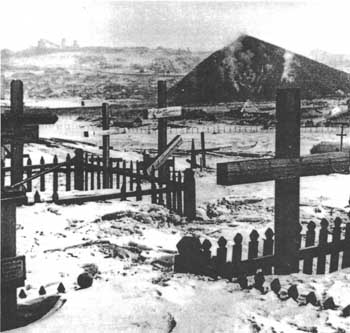

A cemetery at a coal mine in the Vorkuta complex of penal camps, 1956. The Latin crosses may mark the graves of some of the tens of thousands of Poles, many of them veterans of the underground Home Army, deported by the Soviets at the end of the Second World War. Some estimates put the mortality rate of the Poles in the Vorkuta mines at fifty percent.

After Stalin

After the war, the most wretched and hazardous work continued to be relegated to the inmates of the Gulag. Thus, under the direct supervision of secret police chief Lavrenty Beria, thousands of Gulag inmates were used to support the Soviet nuclear bomb project by mining uranium and preparing test facilities on Novaya Zemlya, Vaygach Island, Semipalatinsk, and dozens of other sites. Later, the Soviet navy employed Gulag prisoners to rid decommissioned nuclear-powered submarines of radioactivity.

In 1953, the year of Stalin’s death, the Gulag held around 2.7 million prisoners. Over the next two years the number of inmates fell rapidly – which is not to say that the Gulag withered away under Stalin’s successors.

Danchik Sergeyevich Baldaev, an MVD major who worked in the Gulag from 1951 until his retirement in 1981, has published a book of drawings depicting the travails and agonies of Russians and others declared “enemies of the people” in the post-Stalin Gulag. Baldaev’s book is arranged thematically, with sections on camp organization, tortures and cruelties, sex, food and housing, climatic conditions, common and political criminals, and so on. Despite his own past and the horrors of his topic, he succeeds in depicting the entire pathology of the Communist camps and their overlords in an almost clinical manner, starkly and without theatrics.

As Baldaev makes clear, while officially the KGB administered the operation of the camps, unofficially, inside the barracks, common criminals (murderers, rapists, and psychopaths of every variety) ruled, using and abusing the women and the weak. Calling themselves “vory v zakone” (literally, thieves within the law, the type of which is a ceremonially installed criminal leader who decides disputes and divides spoils), these thugs were Mafiosi of the lowest type.

Women in the Gulag were preyed upon from all quarters. During their transport to the camps they were often raped on the transport ships or in the railroad cars. Upon arrival at their destination they would be paraded naked in front of the camp officials, who would select those they fancied, promising easier work in exchange for sexual favors. These officials, according to Baldaev, preferred German, Latvian, and Estonian women, who most likely would never see home again, over native Russian women, who might. Women not selected by the camp officials became “prizes” for male (and sometimes lesbian) criminals. Besides the everyday tortures of starvation, work exhaustion, exposure to the cold of the far north, and physical abuse, the more intractable prisoners of either sex might be subjected to isolation, impalement, genital mutilation, or, more mercifully, a bullet in the back of the head.

Empire of Death

It is estimated that more than thirty million prisoners entered the Gulag during the half century in which it flourished. Not all of them perished, of course. Short termers, especially, might endure their five-year sentence and be released. In some cases, however, prisoners who had served their time in the Gulag were denied return to their homes, and forced to live out the remainder of their lives in towns near the camp. Robert Conquest, who of Western scholars has done the most to investigate and to reveal the crimes of the Soviet regime, estimates that one out of every three new inmates died during the first year of imprisonment. Only half made it through the third year. Conquest estimates that during the “Great Terror” of the late 1930s alone, there were six million arrests, two million executions, and another two million deaths from other causes in the camps. It is Conquest’s belief that, by the time of Stalin’s death in 1953, about twelve million had perished in the Gulag. Certain investigators, such as the late Andrei Sakharov, have put the figure much higher, from 15 to 20 million. These apparent discrepancies result from honest historians studying crimes, committed in a closed society, of a magnitude never before seen, without reliable documentation.

A grotesque ritual evolved for the thorough disposal of the wasted bodies of inmates who had succumbed to hunger, exhaustion, exposure, and malnutrition. A wooden marker with the deceased inmate’s identification number was affixed to his left leg, and gold teeth or fillings pried out. To ensure that the death was not feigned, the skull of the inmate was smashed with a hammer, or a metal spike driven into the chest. The near naked corpse would then be removed from the camp area and buried in an unmarked grave.

Voices against Oblivion

In recent years various German groups have, with the cooperation of the Russians, been establishing memorials for the German civilians and soldiers who died in the Soviet Union. Recently, a Russian Jew, Aleksandr Gutman, produced a documentary film in which he interviewed four German women from East Prussia who as young girls had been raped by Red Army troops, then transported soon after the war to a particularly hellish outpost of the Gulag, no. 517, near Petrozavodsk in Karelia. Of the 1,000 girls and women who were transported to that camp, 522 died within six months of their arrival. These women were among tens of thousands of German civilians, men and women, deported, with the acquiescence of the Western powers, to the Soviet Union as German “reparations-in-kind” for slave labor. One of the women interviewed by Gutman remarks: “While the diary of Anne Frank is known throughout the world, we carry our memories in our hearts.” Recently, German philanthropists established a memorial cemetery for those women who perished in slave pen no. 517.[2]

After rejection by numerous film festivals due to its “controversial” nature, Gutman’s Journey Back to Youth (Russian title: Puteshestviye v yunost) was finally accepted by the 34th International Film Festival in Houston, Texas, where it won the top prize – the Platinum Award – for 2001 (the film subsequently earned the U.S. International Film and Video Festival’s Gold Camera award). When Gutman attempted to show the documentary in New York City, however, it opened and closed to such taunts as: “He should be killed for making such a movie. Shame, a Jew describing the sufferings of Germans.”

The Perversion of Memory

Today we Americans, from children to dotards, are bombarded with Holocaustiana, a saturation that borders on, and in some case results in, Holocaustomania. Yet rarely are we informed of the cruel purposes and the sadistic workings of the Soviet labor camps. More than half a century after the end of the Second World War, the U.S. Justice Department maintains a special branch – the Office of Special Investigations – exclusively dedicated to the investigation, prosecution, and deportation of former Axis soldiers and officials. Most of those who have been prosecuted served as low-ranking guards at wartime German camps. But no such American office has ever been created to hunt out the officials who headed and ran the Communists’ camps. The most recent book on the Gulag, Smirnov’s System of Corrective Labor Camps, lists more than five hundred camps with their administrative officers through the 1960s. More than a few may well be U.S. citizens today. If our leaders were suddenly to be fired with the same passion for pursuing Soviet persecutors that they have for tracking old Nazis and alleged terrorists, Smirnov’s book might be the place to start.

While many of Germany’s concentration camps have been preserved (some would say enshrined), and are evidently intended to be maintained in perpetuity as memorials to their former inmates and to the wickedness, not only of their jailers, but of the entire German people, the far more extensive Soviet Gulag camp system has in the past decade continued to disappear from the Russian landscape, and from collective memory.[3]

Recent attempts of former inmates of the Soviet labor camps to establish (at the very least) a museum of the Gulag have been frustrated by higher authorities. As Yuri Pivovarov, director of the Institute of Social Science Research at the Russian academy of Sciences, puts it: “People simple do not equate the ethical and moral horrors and shame of Nazism with those of Communism.” Many who now object to the idea of a museum were formerly high-ranking Communist officials, who today steer Russia into the New World Order. Then, too, the Soviet Union was never conquered, and thus never subject to conquerors’ demands.

Among the Forgotten

Not long ago the well-known British travel writer, Colin Thubron, trekked across Siberia. During his journey Thubron deliberately departed the usual itinerary to view the ruins of two notorious Gulag camps: Vorkuta and Kolyma.[4] In his recent book In Siberia, Thubron describes them with a grim lyricism:

Kolyma was fed every year by sea with tens of thousands of prisoners, mostly innocent. Where they landed, they built a port, then the city of Magadan, then the road inland to the mines where they perished. People still call it the ‘Road of Bones.’ … Kolyma itself was called ‘the Planet,’ detached from all reality beyond its own – death.

Of his visit to the dread Vorkuta, Thubron writes:

Then we reached the shell of Mine 17. Here, in 1943, was the first of Vorkuta’s katorga death-camps. Within a year these compounds numbered thirteen out of Vorkuta’s thirty: their purpose was to kill their inmates. Through winters in which the temperature plunged to -40 F, and the purga blizzards howled, the katorzhane lived in lightly boarded tents sprinkled with sawdust, on a floor of mossy permafrost. They worked twelve hours a day, without respite, hauling coal-trucks, and within three weeks they were broken. A rare survivor described them turned to robots, their grey-yellow faces rimmed with ice and bleeding cold tears. They ate in silence, standing packed together, seeing no one. Some work-brigades flailed themselves on in a bid for extra food, but the effort was too much, the extra too little. Within a year 28,000 of them were dead … Then I came to a solitary brick building enclosing a range of cramped rooms. They were isolation cells. Solzhenitsyn wrote that after ten days’ incarceration, during which a prisoner might be deprived even of clothing, his constitution was wrecked, and after fifteen he was dead.

Departing Vorkuta, Thubron stumbled on a stone on which a message had been scratched. It read:

“I was exiled in 1949, and my father died here in 1942. Remember us.”

Notes

| [1] | Jacques Rossi, The Gulag Handbook (New York: Paragon House, 1989); M.B. Smirnov, et al., Sistema ispraviltel’no-trudovykh lagerey v SSSR. 1923-1960 (Moscow: Zven’ya, 1998); Ralf Stettner, Archipel Gulag: Stalins Zwangslager: Terrorinstrument und Wirtschaftsgigant [The Gulag Archipelago: Instrument of Terror and Economic Giant] (Munich: Ferdinand Schöningh, 1996); Danchik Sergeyevich Baldaev, Gulag Zeichnungen (Frankfurt am Main: Zweitausendeins, 1993); Avraham Shifrin, The First Guidebook to Prisons and Concentration Camps of the Soviet Union (New York: Bantam Books, 1982); and Stéphane Courtois, et al., The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression (London: Harvard University Press, 1999). |

| [2] | Aleksandra Sviridova, in V novom sverte (In the New World), a Russian-language newspaper published in New York, May 18–24, 2001, pp. 14–15. |

| [3] | Only recently, however, Dr. Judith Pallot, a geography lecturer at Oxford University, reported that at least 120 “forest colonies” (forced labor camps) dating from the Stalin era are still being used to house tens of thousands, all of them common criminals as opposed to the mix of former years. The camps Dr. Pallot reports on are located in the Perm region of the Northern Urals. The average yearly temperature in that region is about minus 1° C (c. 30.8° F), although during the long winter from October to May it falls as low as minus 40° C (c. -40° F). As in Czarist times, many prisoners choose to remain as settlers in the vicinity of the camps when their sentences have ended. Michael McCarthy, “Thousands of Russian Prisoners Are Still Suffering in the Gulag Archipelago,” in http://www.independent.co.uk. |

| [4] | Colin Thubron, In Siberia (New York: HarperCollins, 1999). |

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 21, no. 1 (January/February 2002), pp. 29-36

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a