Talking Frankly about David Irving

A Critical Analysis of David Irving's Statement on the Holocaust

I first became aware of David Irving about 1992 during the period (1988 – 1995) when he acquired the reputation of being a “notorious Holocaust Denier.” The David Irving of that time was an inspiring figure. He espoused the idealism of pursuing truth rather than profit. He was a fearless iconoclast. The fact that he was already a celebrity historian (for example having been discussed in Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five as the author of the book about Dresden, and having appeared on Leonard Nimoy’s In Search Of as an expert on Eva Braun) made his stand for the cause of Holocaust Revisionism all the more impressive. This was a man who had status and something to lose, who was nonetheless championing the most controversial of truths. The persona that David Irving projected in that period resonated with my own ideals and encouraged me to live up to them.

After his testimony for Ernst Zündel in1988, David Irving seemed to be an intellectual hero in full self-actualization. He said in a 1988 speech that he knew that he had “joined the ranks of the damned” and that the next five to ten years would be difficult, but that he would persevere. David Irving’s stand for Holocaust Revisionism seemed to be an expression of his long-evident character as the historian who intended to correct the omissions and distortions of victors’ history. Holocaust Revisionism seemed to be consistent with the essence of David Irving, the logical next stage in the evolution of the heroic historian.

But in retrospect, with greater knowledge, one can see that David Irving’s truth-advocacy was never entirely free of hesitation. While David Irving seemed to be an uncompromising truthteller, one can just barely discern the influence of calculated self-interest and the moistened finger in the breeze, even in his most outspokenly controversial period. The seed of retreat was always there.

For example, in that 1988 speech, wherein David Irving proclaims that he is now an “unbeliever” in the Auschwitz gas-chamber story, and that the whole gas-chamber story is likely false, he balks at blaming Jews for the lie. Instead, he claims that British psychological warfare put out the gas-chamber story “quite cold-bloodedly” — although documents of the British government (visible on Irving’s own site) indicated that the British psychological warfare executive was repeating a story that came to them from Jews. I assume that David Irving learned of all of these documents (unearthed by Paul Norris) at about the same time, whence it follows that David Irving knew, when he said in 1988 that the British had invented the gas-chamber story, that it really came from Jews.

All of this points to a fear of the Jews that was never entirely overcome. Jewish power is, after all, a serious matter for a commercial author who depends on the Jewish-dominated publishing industry for his livelihood.

It seems that David Irving believed that he could minimize conflict with Jews by minimizing Jewish responsibility for the Holocaust-lie. During that 1988 speech, as Irving explains how Jews themselves are supposed victims of the lie, a man in the audience blurts out, “You’re very generous!” In 1988 David Irving was indeed generous in his assessment of the role of Jews in promoting the Holocaust, but that generosity did not save him from Jewish odium and organized Jewish harassment.

In 1996, when Goebbels: Mastermind of the Third Reich appeared, it became clear that David Irving was in retreat, and trying to appease his enemies by writing a book that slammed a leading figure in Hitler’s Germany while showing sympathy toward Jews.

I heard a prominent Holocaust Revisionist at that time remark (privately) that David Irving had been accustomed to living the high life as a famous historian who drove a Rolls Royce, and, contrary to his professed idealism and professed willingness to sacrifice in pursuit of truth, David Irving had embraced Holocaust Revisionism with the expectation that it would be the next big thing in modern historiography, and that he would benefit from having gotten into it early – not realizing how adversely the Jewish backlash would affect his lifestyle and interfere with his career.

In other words, David Irving was never as idealistic as he professed to be. However impressive, however convincing and inspiring he seemed in the period from 1988 to 1995, David Irving was more heroic tenor than hero. This is clearer than ever today.

During the failed libel-suit against Deborah Lipstadt and Penguin Books in 2000, Irving complained extensively about the pecuniary loss that he had suffered as a result of Jewish propaganda against him as a “Holocaust Denier.” With that suit he was trying to escape the label “Holocaust Denier,” and in 2016 he seems to be still trying.

These days, David Irving actually promotes the proposition that there really was some kind of Holocaust, and, although he has not retracted his endorsement of the Leuchter Report (which he himself republished in 1989), on the whole he is not only trying to distance himself from Holocaust Revisionism but indeed working against it.

A big part of the problem with David Irving is the lack of rigor in his reasoning. Because he never bothers to define the term Holocaust, and never specifies how it is supposed to have happened, David Irving is able to say:

“How many died in the Holocaust? … Well the answer is: a lot.”

It is always an inauspicious beginning to a discussion of the Holocaust when the term is left vague and undefined, because it means that every Jew who died of a disease, and every Jewish criminal who was punished, and even every Jew whose whereabouts were unknown after the war, may be counted as a victim of the Holocaust. Anyone who embarks on such a discussion without defining the term has already decided that the number who died in the Holocaust will be “a lot.”

Most of “Talking Frankly” is autobiographic, but in the final segment David Irving presents a revised version of the Holocaust that salvages as much of the genocide-accusation as can be salvaged without contradicting the Leuchter Report. There are three main elements here. The order in which he presents them reflects their importance in retreating from the quasi-heroic stand that he took in 1988. First he makes a partial retreat from his position on Auschwitz; then he asserts that many Jews were killed in the Operation Reinhardt camps; finally, he plays up an alleged mass-shooting of Jews that is supposed to have happened in 1941.

David Irving Increases his Death-Toll for Auschwitz (1:32:38 – 1:35:43)

In 1995, David Irving endorsed a death-toll for Auschwitz of only 100,000 Jews:

“If we look just at the case of Auschwitz, I think probably as many as 100,000 Jews died in Auschwitz, which is a brutal slave-labor camp where they had no business to be. The fact that they died in that camp of ‘natural causes’ – epidemics, mostly typhus – is neither here nor there. Of those 100,000 probably about 10,000 were actually physically murdered in the criminal sense. The rest … fell by the wayside in Auschwitz.” (David Irving, Cincinnati 1995,1:31:50-1:32:22)

The number that Irving gave for the Jewish Auschwitz death-toll in 1995 resembles the estimate, "100,000-150,000" of which "a large number would have been Jews," that Arthur Butz gave in 1989 (A. Butz, JHR, fall 1989).

Irving’s claim that 10% of the 100,000 Jews were murdered, however, was obviously gratuitous (since any SS-personnel discovered to have murdered even one inmate would have been punished) and, in retrospect, a harbinger of his eventual retreat from Revisionism. David Irving in 2009 has this to say about the death-toll at Auschwitz:

“There is a video showing the actual judgment being handed down on them. The judgment was handed down, and in the judgment it says, these people who are guilty today have been the principal officers of a camp, Auschwitz, in which up to 300,000 people of all nationalities met their deaths, came to an end. It doesn’t say they were killed; it doesn’t say they were gassed. It just says they died – up to 300,000.

“Now these, you’ve got to realize this was the Polish courtroom which had all the Auschwitz documents, and all the Auschwitz prisoners to interrogate, and the figure they used in their judgment as they sentenced these men to death was up to 300,000.

“So how, suddenly, did the figure balloon to 4,000,000 on the memorial in Auschwitz in the 1970s and 1980s?

“The Communist director – the Jewish director – of the Auschwitz State Museum, Franciszek Piper, he eventually had that figure chiseled down, and a new monument erected to the 1.2 million killed.

“You notice, it’s rather like Monopoly money, the way they play around with these figures. (1:34:35 – 1:35:43)

Irving here opines about death-tolls claimed for Auschwitz with what seems to be inadequate knowledge of the history of such claims. He implies that there has been wild variation, but the Communist line about how many died in Auschwitz, although universally acknowledged as false today, was quite consistent during the period of Communist rule, as autocratically dictated “truth” ought to be.

The figure of “more than 4,000,000” killed in Auschwitz (which was supposed to include systematically genocided Poles as well as Jews) was promulgated as the official position of the Soviet government on 7 May 1945, and was uncritically repeated by Western news-media (AP, 7 May 1945). The same number was then used by the Communist government of Poland in prosecuting the former commandant of Auschwitz, Rudolf Hoess, at Krakow in March 1947 (AP, 11 March 1947, AP, 16 April 1947).

In the second Auschwitz-trial staged in Krakow, in November and December 1947, 40 other Germans were prosecuted. It is to this trial that David Irving refers. According to the Associated Press, the death-toll alleged at this trial was the same as in the previous Auschwitz-trial, and consistent with the 1945 decree of the Soviet government:

“The prosecution had estimated that 4,500,000 people died from starvation, torturing, hanging and in the gas chambers at Auschwitz….” (AP, 22 December 1947)

If the report of the Associated Press on the second Auschwitz-trial was correct, then the Communist line of (at least) 4 million dead for Auschwitz was consistently maintained until after the collapse of the Polish People’s Republic in 1989, whereafter the figure was reduced to a less outrageously untenable figure (AP, 18 July 1990).

David Irving seems to assume that facts – “all the Auschwitz documents, and all the Auschwitz prisoners to interrogate” – were relevant in the Krakow trials. But Communist show-trials are not about justice; they are about political propaganda. In such trials the prosecutors and judges are on the same team, the defendant is presumed guilty, and a verdict that substantially contradicts the indictment is simply not possible. It means that the report that this trial made a finding of only 300,000 deaths at Auschwitz – substantially contradicting the Soviet line – cannot be correct.

The video to which David Irving refers does exist. It is a Welt im Film newsreel of 8 January 1948. Welt im Film was a propaganda-arm of the British and American occupation-authorities; as a tool of “re-education” it cannot be considered a highly trustworthy source. Why would Welt im Film have misreported the second Auschwitz-trial’s finding? Perhaps because a report of 4.5 million dead in one camp would have sparked incredulity in the German viewers.

Irving has always boasted of his reliance on primary sources, searching for original documents and interviewing eyewitnesses. But in this instance, relying on a newsreel issued by British and American occupation-authorities instead of a document from the trial, he failed to live up to his own espoused principle.

There were gassings at Auschwitz after all! (1:36:54 – 1:39:41)

Within Holocaust Revisionism, David Irving has been most consistent in his support for the findings of the Leuchter Report, which explained that the extant structures at Auschwitz-Birkenau (and Majdanek) could not have been used as homicidal cyanide gas-chambers. Auschwitz-Birkenau, at the time when Leuchter wrote his report, was represented as the most important site of mass-murder of Jews, with an alleged death-toll of 2.5 million Jews (and 1.5 million others) still claimed at that time (M.C. Vita, AP, 7 May 1985). Auschwitz also had great symbolic importance from having been featured in the NBC miniseries Holocaust (1978) which popularized the use of the word Holocaust as a proper noun. Thus, the most important claim of the Jewish Holocaust-legend was shown to be false by the Leuchter Report. It was especially David Irving’s support for the findings of the Leuchter Report, which he republished in a glossy edition under his own Focal Point imprint, that caused Irving to be labeled a Holocaust Denier.

In 1988 it was evident that Leuchter’s finding about Auschwitz had cast a shadow of doubt over the entire Holocaust-narrative for David Irving. In 1988 he used expressions like “six-million fake” and “the whole Holocaust mythology.” Later, in a subtle softening of his position, he used the term “Holocaust legend.” (This was a softening insofar as a legend is not necessarily a lie, nor even false.)

By 2009, however, David Irving has advanced so far in the effort to mitigate his heresy that he alleges limited gassings at Auschwitz. The claim necessarily pertains to structures that no longer exist, which Fred Leuchter consequently could not examine.

The Auschwitz “bunkers,” also called the “white house” and the “red house,” were rumored to have been sites of gassings, but according to revisionist Carlo Mattogno the stories about the white house and the red house vary to such a degree that the identification and location of those structures, and even their existence, is in doubt – although Irving speaks as if what the Auschwitz Museum designates as the locations of the white house and the red house were definitely correct.

As evidence for gassings in the Auschwitz bunkers, David Irving in 2009 adduces an account given by a former deputy-commandant of Auschwitz, Hans Aumeier, which Irving discovered in the British Records Office in 1992.

David Irving saw good reason for not trusting Aumeier’s account when he discovered it. He wrote in his diary in June 1992:

“Finished reading file of interrogations and manuscript by one SS officer, Hans Aumeier, a high Auschwitz official. Once again, like Gerstein, his reports grow more lurid as the months progress. I wonder why? Beaten like Höss or was he finally telling the truth?” (quoted in transcript of Irving-Lipstadt trial, 2 February 2000, also quoted by Guttenplan)

Irving wrote essentially the same in a contemporary letter to Mark Weber, along with an exhortation that revisionists should analyze the file on Aumeier before the Holocaustians get hold of it:

“Working in the Public Record Office yesterday, I came across the 200 page handwritten memoirs, very similar in sequence to the Gerstein report versions of an SS officer, Aumeier, who was virtually Höss’s deputy. They have just been opened for research. He was held in a most brutal British prison camp, the London Cave [Cage] (the notorious Lieutenant Colonel A Scotland)… It becomes more lurid with each subsequent version. At first no gassings, then 50, then 15,000 total. Brute force by interrogators perhaps.” (Ibid.)

Irving also discussed the confession briefly in an endnote from his 1995 tome about the IMT at Nuremberg, where he added this observation:

“The final manuscript (or fair copy) signed by Aumeier was pencilled in British Army style with all proper names in block letters…. Aumeier was extradited by the British to Poland and hanged.” (Irving, Nuremberg the Last Battle, p. 534)

What Irving implies by observing the style in which the confession was written, is that Aumeier did not write it. The so-called document is a creation of the British government, not an authentic statement from Hans Aumeier, Irving implies.

Nonetheless, David Irving today relies on what he knows to be Aumeier’s tortured confession as evidence that Jews who could not be used for labor were gassed in Auschwitz’s white house and red house. Irving diverts attention from that problem by pretending that the real problem is whether the papers recording the tortured confession are genuine:

“So these gassings did occur, if you accept that these papers aren’t fake, and I don’t believe for a moment they are fake.”

The question of course is not about whether the papers themselves are genuine; nobody doubts that CSDIC produced these documents. The question is whether the statements that they contain are accurate, because it is well known, and David Irving knows, that CSDIC extracted false confessions and compelled its prisoners to sign them.

At the time of the libel suit against Deborah Lipstadt and Penguin Books in 2000, the truth about the London Cage was not so well known. Irving’s statements to the court at that time about the torture of German prisoners in British custody consequently met with skepticism. In 2012, however, the fact that CSDIC tortured German prisoners and compelled them to sign false confessions became quite well known, with the appearance of Ian Cobain’s Cruel Britannia: A Secret History of Torture. Although Cobain does not specifically mention Aumeier, the book gives a general idea of what happened in the London Cage, and was favorably reviewed. David Irving's decision to pretend belief in Aumeier's confession was thus ill-fated.

The Operation Reinhardt Camps (1:39:42 – 1:52:20)

“So, is David Irving a Holocaust Denier? I don’t think so….” (1:39:42 – 1:39:47)

Irving says that he is not a Holocaust Denier because he now asserts that millions of Jews were killed in the Operation Reinhardt camps.

Early in his discussion of those camps, Irving makes a bizarre assertion about Holocaust Revisionists:

“And here is where I say I have to cross swords with the main Revisionist body. They don’t want to believe the Reinhardt camps exist. I think the Reinhardt camps did exist.” (1:40:46 – 1:40:57)

This was an astonishing statement. There is no Holocaust Revisionist who says that the Operation Reinhardt camps never existed. On 5 April 2016 I asked David Irving which revisionist claims that these camps never existed, and he was kind and humble enough to respond:

“I don’t know.”

The motive for saying that “the main Revisionist body” denies that the Reinhardt camps existed is obviously to create distance between himself and those awful Holocaust Deniers, but Irving has blatantly overstepped the bounds of truth here (although an audience of university-students might not suspect it). The statement could be used as evidence that David Irving is really not, as he likes to declare, careful about what he says, but one will see that there is no shortage of evidence for that.

Irving introduces the Operation Reinhardt camps this way:

“It was a thieving operation, a looting operation, The Jews were being sent to these camps, and before they were being liquidated, they were being robbed of everything they had. It was a plundering operation.” (1:40:35 – 1:40:46)

The claim that Jews arriving at the Reinhardt camps were stripped of valuables may be true. But the claim that this confiscation was accompanied by mass-murder (“liquidation”) of Jews is sheer speculation.

Irving does not give any information about how the killing in these camps is supposed to have been done. Much less does Irving cite any witness, most likely because the alleged eyewitnesses to mass-murder in the Operation Reinhardt camps, from Abraham Bomba to Yankiel Wiernik, have all been scrutinized and notoriously lack credibility. Irving therefore entirely avoids citing any of those alleged witnesses.

Instead, Irving constructs an accusation of mass-murder totally apart from what the discredited “witnesses” ever said, based on cherry-picked tidbits from documents. On top of that, he also misrepresents some things. But ultimately even this is not enough, and he must rely on invocations of imagination to compensate for the shortfall in evidence. To put it briefly, this is not serious history, much less “real history.” It is very much like the war-propaganda that David Irving used to reject.

Look at how Irving encourages his listeners to fill in their knowledge-gaps by guessing what a document means:

“Now, the Hoefle document of course is very significant. You don’t have to be a rocket-scientist to guess that T, S, and B, are Treblinka, Sobibor, and Belzec, three of these camps.

You don’t have to be a rocket-scientist to guess what is happening to them in those camps. They are not being processed through them; they are being dealt with in them.” (1:46:12 – 1:46:30)

Look at the rhetoric. First, Irving imparts a modicum of respectability to the act of guessing. It is, after all, obvious enough what “T, S, and B” represent. But then Irving asks his audience to “guess” that Jews were mass-murdered. This is an appeal to vain presumption.

If Irving’s evidence were any good, he would not be telling his listeners to “guess” what is happening in the camps.

Based on the surmise that Jews being deprived of valuables were also murdered, Irving puts the Jewish death-toll for the Operation Reinhardt camps for 1942 and 1943 at “2.2 million people or more.” (1:46:54 – 1:47:02)

There are eight or nine documents to which Irving refers in his discussion of the Operation Reinhardt camps:

- an alleged letter from Heinrich Himmler ordering the demolition of Treblinka and the establishment of a farm on the site (putatively to disguise what had been happening there);

- Himmler’s letter to Heinrich Müller about “Jews dying like flies”;

- Himmler’s letter to Ernst-Robert Grawitz about the low rate of cancer-mortality in the camps;

- two inventories of confiscated valuables from 1942 and 1943;

- the Hoefle telegram;

- the Korherr Report;

- a letter from Himmler to Korherr instructing him on how to word the executive summary of the Korherr Report for Hitler;

- alleged memoirs of Adolf Eichmann.

(1)

This is how David Irving describes Himmler’s letter ordering the demolition of Treblinka:

“There is a letter in the private papers of Heinrich Himmler, which says, when the operation in Treblinka is finished, I want the whole site demolished and removed. Nothing must remain. I want the whole site grassed over, and a farmhouse, a farmstead built there in its place, which can be given to some Ukrainian to run.” (1:41:43 – 1:41:49)

It seems that David Irving heard of this letter for the first time when the crown prosecutor asked him about it during his 1988 testimony for Ernst Zündel. Mainstream Holocaust-historiography has always interpreted this letter to mean that Himmler had Treblinka demolished so that the advancing Red Army would not discover whatever had been happening there.

This interpretation appeared in 1945 in the VOKS Bulletin. VOKS, the “All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries,” was an entity created by the government of the Soviet Union. VOKS Bulletin stated:

“Lupine was planted on the site of the camp and a settler named Streben built himself a house there. The house is no longer there, for it has been burnt down since.

“What was the Germans’ purpose in this? They wished to hide the traces of the slaughter of millions of people in the Treblinka hell.” (VOKS Bulletin 1945 #1/2, p. 36)

(These sentences, incidentally, also appear with slight alterations in Treblinka survivor Chil Rajchman’s book Treblinka.) In that early published account, a farmhouse was not built by the SS and turned over to a Ukrainian, as Irving says. Rather, the "settler" built his own farmhouse. But fundamentally David Irving has adopted the 1945 Soviet line on what was done on the site of Treblinka and why.

There is, however, another, completely different explanation for when and why Treblinka was demolished. Already on 5 January 1943 the head of Operation Reinhardt, Odilo Globocnik, submitted a report on “the economic winding-up” of the operation. On 19 October 1943 Globocnik had dissolved all the constituent camps and terminated Operation Reinhardt. (IMT transcript, 5 August 1946) The termination of Operation Reinhardt was thus initiated 20 months, and completed 10 months, before the arrival of the Red Army at Treblinka in early August 1944. Consequently the demolition of Treblinka and the restoration of nature on the site does not seem to have been caused by the Red Army’s approach. Also, consider that Majdanek, which was also under Globocnik’s command, was not bulldozed.

There is disagreement about what the alleged settler's name was. VOKS Bulletin gives the name as Streben. Elsewhere the name is given as Strebel. David Irving, on his website, gives the settler's name as Streibel (which happens also to be the surname of the Bavarian commandant of Trawniki labor-camp) (D. Irving, A Radical’s Diary, 2 March 2007). Whether Streibel or Strebel or Streben, it seems an unlikely name for a Ukrainian. If there really was a settler on the site of Treblinka, and one of those names was his name, he was most likely a German.

On his website, David Irving says that the settler was a Ukrainian who had been a guard at Treblinka – which makes a tidier conspiracy-theory than letting the settler be some random Ukrainian, except that the settler is said to have burned down his farmhouse and departed ahead of the Red Army, which negates the entire purpose of establishing a Ukrainian farmer there to disguise the place.

Obviously the settler, if he existed, did not build his farmhouse, nor move into a farmhouse built for him, with the expectation of burning the farmhouse down and fleeing within a few months. The alleged sinister motive for having a Ukrainian farmer settle on the site is not consistent with what subsequently happened. If this settler existed, the most likely interpretation is that he was hoping that the Red Army would not arrive anytime soon.

It would not seem reasonable to interpret the demolition of Treblinka in 1943 as a destruction of evidence, if it were not already assumed that terrible things were done there. David Irving, citing the demolition as implicit evidence of German guilt, thus engages in circular reasoning.

(2)

An important technique that Irving uses to support the claim of mass-murder in the Operation Reinhardt camps is to claim that documents mean something very different from what they actually say. Irving reinterprets a letter from Heinrich Himmler to Heinrich Müller, which seems to demonstrate Himmler’s concern for the wellbeing of prisoners, as actually demonstrating the opposite. Irving says:

“If you really know how to look at the private papers of Heinrich Himmler, the chief of the SS, you begin stumbling across documents that have been clearly written as part of a coverup.

“September 1942. He writes a letter to the chief of the Gestapo, Heinrich Müller, saying, ‘There’s this very disturbing report in the London Daily Telegraph which has come to my hands, which says that the Jews are dying like flies in our camps. I want you to investigate this and find out just what is going on.’

[…]

“The Germans were in the habit of writing what they called Deckungsschreiben, coverup-letters, letters that would exonerate them in the case that things went wrong – alibis. That letter from Heinrich Himmler to the chief of the Gestapo, Heinrich Müller … is a coverup-letter. (1:42:00 – 1:43:11)

Irving pretends to believe that Himmler wrote this letter to create the appearance that he did not know that Jews were being systematically killed in the Operation Reinhardt camps. The problem, which Irving of course does not mention, is that the report of Jews “dying like flies” was specifically about Theresienstadt – not about the camps that Irving is discussing. The United Press carried the story:

“Fifty thousand Jews from Germany and Czecho-Slovakia have been thrown into the Austro-Hungarian fortress at Terezin and several thousand who are ill or charged with ‘criminal’ acts are in underground dungeons where they are ‘dying like flies,’ a Czech government spokesman said last night.” (UP, 3 September 1942)

Note the untrustworthy source: an unnamed “Czech government spokesman.” Arthur Butz quoted from this report in his magnum opus and commented as follows:

“The only truth in this story lies in the fact that the death rate of Jews was rather high at Terezin (Theresienstadt) due to the German policy of sending all Reich Jews over 65 there. Another category at Theresienstadt was the “privileged” Jews – the war veterans – especially those with high decorations. There were other Jews, many of whom were eventually moved out, but if they suffered, it was not at Theresienstadt. The place was visited by the Red Cross in June 1944, and the resulting favorable report angered the World Jewish Congress “ (Butz, Hoax of the Twentieth Century, p. 99)

Irving commits a multiple misrepresentation here, not only ignoring the lack of substance to the report about Theresienstadt, but also pretending that it was about the Operation Reinhardt camps instead. There are also problems with Irving’s claim that the Germans habitually wrote Deckungsschreiben.

The premise that Irving gives for interpreting Himmler’s letter as disingenuous – that the Germans habitually wrote Deckungsschreiben or “alibis” – is a smear against the German military. It was not only Himmler, according to Irving, who did this. The claim that the Germans were habitually arranging alibis for themselves presupposes that they were habitually committing crimes.

Where does Irving get this?

The term Deckungsschreiben, in a context where it denotes something that someone with responsibilities in the German military would write, is quite rare. It appears twice in Albert Speer’s 1981 book, Der Sklavenstaat. Meine Auseinandersetzung mit der SS (“The Slave-State: My Quarrel with the SS”), where Speer twice attributes the writing of Deckungsschreiben to Wehrmacht-General Wilhelm Keitel.

If Speer attributes this practice to Keitel, it does not follow that the use of such Deckungsschreiben was widespread as Irving claims, since the common (most likely unfair) postwar representation of Keitel has been that he, more than others, was a sycophant to Hitler.

Furthermore, the meaning of Deckungsschreiben as used by David Irving has shifted over the years, in a way that makes it more derogatory. Responding to Rabbi Robert Chevins in 1999, Irving defined Deckungsschreiben as:

“… a letter somebody has obtained from his superiors to cover him, just in case. In the case of the extermination of the Jews, had Hitler given such a verbal order, one would have expected Himmler, or Heydrich, or Mueller, or somebody of that ilk to make a Note for the Record, “just in case”; or, less formally, to have mentioned it in a letter-home, or in a private diary ….” (D. Irving to R. Chevins, 15 July 1999)

There is nothing disgraceful in the proposition that men in positions of responsibility would want a written record of an order that might become controversial later, especially if they are operating within a system like the German military with a high level of discipline, where a man might be put on trial and convicted by his own government if he does wrong and cannot produce “superior orders” as a defense. It is simple prudence to make sure that there is a written record of important orders, in case there is any question about who was responsible.

But what David Irving means today with the word Deckungsschreiben is not that the Germans documented commands, but that they were habitually creating false alibis for crimes, which is a very different matter.

There are so many things wrong with Irving’s interpretation of Himmler’s letter to Müller that the most likely explanation seems to be that he was hoping that nobody would check.

(3)

A letter to the chief physician of the SS, Ernst-Robert Grawitz, who had done a study of the causes of mortality in the concentration-camps, wherein Himmler inquires about the low incidence of cancer-mortality in the camps, David Irving reinterprets as a joke.

I doubt that the letter that Irving is calling a joke actually is a joke. On 11 April 2016 I asked Mr. Irving if there was another example of such a “joke,” and where I could read the text of the letter. He said that he did not have time to give another example of such a joke, but that I could find the Himmler-Grawitz letter in the book Reichsführer! by Helmut Heiber.

I found the text of the letter, and noticed that it included details that were incompatible with Irving’s interpretation. Irving is arguing that the reason why none of the prisoners died of cancer was that they did not live to such an age, but Himmler’s letter includes the premise that there were prisoners in that age-group:

“Besonders bemerkenswert ist diese Meldung, wenn man berücksichtigt, daß es nach dem Stand vom 20. 2. 1945 28 145 männliche und weibliche Häftlinge im Alter von über 50 Jahren gibt….”

“This report is especially noteworthy if one considers that, according to the tally of 20 February 1945, there are 28,145 male and female prisoners over 50 years of age….”

Thus, David Irving’s interpretation of the Himmler-Grawitz letter as a sinister joke ceases to be tenable as soon as one knows all of what the letter says. Obviously he was hoping that nobody would check.

Irving compares his (mis)interpretation of the Himmler-Grawitz letter to a supposed explanation of what is known as the French paradox, i.e. the low incidence of heart-disease among French people. Irving claims that the low mortality from heart-disease is due to a high mortality from cirrhosis of the liver. That is an entertaining parable but it is not true. Although the occurrence of heart-disease among the French is relatively low, and the occurrence of hepatic cirrhosis is relatively high, hepatic cirrhosis even among French people, affecting not more than .5% of the population (The Burden of Liver Disease in Europe, EASL, 2013, p. 10), is not nearly common enough to account for their low rate of heart-disease. David Irving certainly does not let truth get in the way of a good story.

(4)

Irving tells us that among the German documents held by the Hoover Institution are two reports, for 1942 and 1943, on the quantities of valuables confiscated (“loot,” Irving calls it) from Jews under Operation Reinhardt (“a thieving operation,” Irving calls it). Irving tries to parlay an inventory of confiscated wealth into evidence of mass-murder:

“And it makes very grisly reading. The two documents list all the watches, and fountain-pens, and gold coins, and everything that had been taken off all the people that had been passing through Operation Reinhardt…. Very interesting, because it gives you a pretty clear idea of people who no longer need their wristwatches and fountainpens and gold coins. Something is happening to them….” (1:44:41 – 1:45:20)

The two pages were discussed during Irving’s trial in 2000. It is not a fact explicitly stated in the source, but a mere inference, that the valuables were taken without specific justifications from Jews passing through the Reinhardt camps. The pages themselves indicate that the valuables had been stolen by Jews (Irving libel-suit, day 17) before being taken back from the Jews, but Irving does not accept that.

There is also no indication that each wristwatch and fountainpen came from a different Jew. If they came from a relatively small number of Jews that had hoarded large quantities of valuables, that would be very different from what Irving portrays.

Be that as it may, Irving is certainly making too much of it. What is so “grisly” about an inventory of valuables? To call an inventory of valuables “grisly” is reminiscent of the way Auschwitz-believers have interpreted “masses of hair, piles of shoes and mounds of eyeglasses, artificial limbs, suitcases and baby clothes.” (Drusilla Menaker, AP, 19 February 1990). David Irving certainly recognizes the fallacy of this kind of interpretation applied to Auschwitz, and he must therefore understand that he is committing the same sin in regard to Operation Reinhardt.

(5)

Some years ago when Irving started presenting the Hoefle Telegram as evidence for mass-murder, he encountered this obvious criticism, directed to him repeatedly by an irate Paul Grubach:

“Does the Hoefle document, the piece of ‘evidence’ that changed your mind on the Holocaust, does it specifically mention ‘homicidal gas chambers’ or the ‘mass murder of Jews’ in various concentration camps in any spot?

“A simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ will suffice.” (A Radical’s Diary, 12 October 2007)

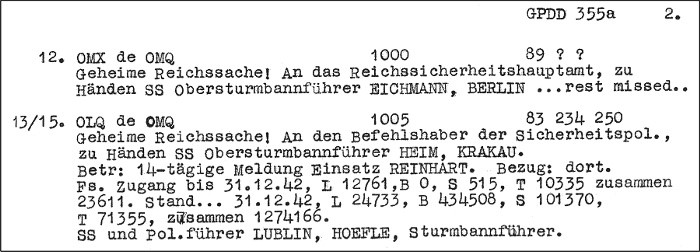

In fact there are three criticisms that can be made of David Irving’s use of the Hoefle Telegram as evidence for mass-murder in the Operation Reinhardt camps. The most obvious point is that the telegram says nothing about killing anyone. Irving offers a criticism of his own, which is that the document carries indications of being fake. I also have a criticism of how David Irving somewhat misrepresents the Hoefle Telegram in this “Talking Frankly” video. I shall explain the last point first.

Early in his discussion of the Reinhardt camps, Mr. Irving mentions Majdanek just once, when he names the camps:

“There was Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka. And on top of that came the camp called Majdanek. You can go and visit all these camps in Poland now, but the reason they’re not on the tourist-route is because there’s nothing to see. There’s no buildings you can see, no execution-walls, no buildings described as crematoria or gas-chambers. There are just bald patches in the middle of a forest.” (1:41:04 – 1:41:26)

Although he mentioned Majdanek, none of what David Irving just said is true of Majdanek. The camp is mostly intact, with several alleged gas-chambers and a (rebuilt) crematorium shown to tourists.

In fact, Majdanek was one of the camps examined by Fred Leuchter. Majdanek is in the original Leuchter Report. Earlier in this talk, Mr. Irving gave a warm endorsement to Fred Leuchter and his findings about Auschwitz, but did not mention Leuchter’s examination of Majdanek and his conclusion that nobody was gassed there.

When Majdanek was captured by the Red Army in 1944, it was “estimated by Soviet and Polish authorities” that “as many as 1,500,000 persons” had died in the camp (W.H. Lawrence, New York Times News-Service, 30 August 1944). The figure of “about 1½ million persons” also appeared in the 1945 indictment of “major war-criminals” (IMT transcript, 20 November 1945). Today, by contrast, a publication of the Israeli Holocaust museum, Yad Vashem, states that only “150,000 people” were ever even incarcerated at Majdanek, where “up to 45,000 prisoners could be housed … at a time.” In 2007 Tomasz Kranz estimated that 60,000 Jews and 18,000 others died in the camp (Yad Vashem publication Majdanek ). At Majdanek, the myth of the Holocaust has been in a precipitous retreat.

Mr. Irving omits to tell his audience that Majdanek is in the Hoefle Telegram. He says “T, S, and B,” but it is really T, S, B, and L. “L” would be Lublin, which is another way to designate the camp at Majdanek, since Majdanek is within the city of Lublin.

Why that omission? Because there is less free play for paranoid imaginings about a camp that is still standing and can be examined, compared to “bald patches in the middle of a forest”:

"To me, that is far more evocative, far more lonely and sinister, when you go into the middle of this forest and suddenly there is a one or two kilometer square bald patch, where nothing seems to have happened." (1:41:28-40)

Majdanek, furthermore, has been thoroughly debunked as a supposed killing-center. David Irving chooses not to mention that Majdanek is in the Hoefle document because he does not want an intrusion of humdrum reality into his imaginative story.

In February 2002, in a polemic directed at Pierre Vidal-Naquet, a Jewish defender of the Holocaust-faith who was reckless enough, even before David Irving, to refer to intercepted and decrypted telegrams from the Second World War as new evidence for the Holocaust, Professor Robert Faurisson wrote:

“In the first place, these telegrams were intercepted and deciphered by British specialists about sixty years ago. At the time, the information that they contained was required to be immediately evaluated and taken into consideration by all interested parties – army, economy, propaganda – and shared with the Americans. All of that was explained in 1981 in F.H. Hinsley’s work British Intelligence in the Second World War: Its influence on Strategy and Operations, Volume 2 (Cambridge U. Press, 1979). Incidentally, one finds on page 673 of this book the following sentence: “There were no references in the decrypts to gassing.” (R. Faurisson, “Pierre Vidal-Naquet à Lyon”, 23 February 2002)

David Irving has long been aware of that sentence from Hinsley’s book; he quotes it to Robert Jan van Pelt in a letter dated 29 May 1997. The entire page from Hinsley’s book is reproduced on Irving’s blog.

In addition to Hinsley's note about the absence of references to gassing in decrypted radiotelegrams, David Irving in 1988 considered it highly significant that no other known German communications contained any such reference either:

“We know exactly what people knew at that time, because the Gestapo kept what are called morale reports, Stimmungsberichte, and these are complete and intact in the archives in Koblenz, and we know exactly what happened because people wrote letters and diaries. And they wrote letters to each other which were intercepted by the British secret service. Millions of letters were intercepted by the British…. We got hold of thousands of sackfuls of private letters written by people, and these letters were then sorted and read and analyzed, and reports were written on the content of these letters, and nowhere – and I’ve read these reports – nowhere is there the slightest reference to any Germans during the Second World War knowing about details of gas-chambers and gas-camps.”

Thus the Hoefle document, if it really were an intercepted communication referring to mass-murder by gassing, would be entirely unique. But the Hoefle document does not say anything about killing anyone, with gas or otherwise.

Faurisson explains that the Hoefle document only seems to be evidence for the Holocaust if one imaginatively “decodes” it instead of simply reading it:

"In 2001 two authors, Peter Witte of Germany and Stephen Tyas of Britain … claimed like so many others that they had just unearthed a 'new document,' although it was an item long known. Their study appeared in the periodical Holocaust and Genocide Studies (vol. 15, no. 3 [winter 2001], pp. 468-486) under the title: 'A New Document on the Deportation and Murder of Jews during ‘Einsatz Reinhardt’ 1942.' […] Since the appearance of their study, the authors have been forced to admit that in reality the document in question is not as new as their title had promised. The British were familiar with it and had deciphered it during the war. But, behold, our two authors think that the deciphering had been only “partial.” For them, the British had seen clearly that there were 'deportations' but they had failed to understand what these deportations meant — the death of all the deportees. In reality the British had noted, just as we can today, that the German text speaks only of 'Umsiedlung,' of 'umgesiedelt' and of 'durchgeschleust.' That is to say, about 'resettlement,' about persons 'resettled,' and about persons 'passed through' the transit camps. The British made nothing more of it, and rightly so."

Once again David Irving, along with Witte and Tyas, engages in circular reasoning. Having interpreted Hoefle's telegram in the light of belief in the Holocaust – which the British experts during the war did not have – they then turn around and use their interpretation as evidence for the belief that generated it.

Each of the four camps mentioned in the Hoefle document, B, T, S, and L, has numbers listed under the categories Zugang and Stand.

On Irving’s site, a letter from Michael Mills says that the word Zugang is problematic because in the jargon of German concentration-camps Zugang, Mills tells us, normally refers to people arriving at a camp to stay, an increase in the camp’s population, not people sent to a camp just to be killed. For example, hardcore Communists segregated from other POWs and sent to Auschwitz for execution were not counted as Zugang. Irving in this talk totally ignores that problem. (M. Mills, “Some Problems with Interpreting that Intercept about Arrivals at B, S,T, L,” 27 January 2002)

Stand appears in the previously discussed letter from Himmler to Dr. Grawitz, where it refers to a tally of (living) prisoners. Himmler writes to Dr. Grawitz that he finds the low cancer-mortality in the camps surprising, because the Stand, he says, indicates that there are many (living) prisoners in the camps of such an age as to be prone to cancer. If we are to assume that the SS used words with consistent meaning to avoid confusion, then Stand in the Hoefle document would most likely refer to a count of living prisoners.

Fundamentally, the Hoefle document only seems to have a sinister significance if one brings sinister assumptions to it. That is to say: if one already believes that the name Eichmann and the security-classification geheime Reichssache imply something nefarious, and that deporting Jews really means killing Jews. Decades of Holocaust-propaganda are the reason why Tyas and Witte could perceive the Hoefle Telegram as incriminating while the experts in Bletchley Park who originally handled the information did not. But why does David Irving see anything sinister in it? He is supposed to be the representative of Real History, the Englishman who has overcome the influence of propaganda.

David Irving’s last point about the Hoefle Telegram is that he somewhat doubts the document’s authenticity. The reasons that Irving gives in 2009 for doubting the document's authenticity seem, at least to a non-expert, very convincing:

“First of all let me say that I’m 80% sure the document is genuine – the Hoefle document – but there’s a 20% nagging, residual doubt. The document contains anomalies. First of all, it and the corresponding document that goes with it are addressed to Adolf Eichmann. Now, Adolf Eichmann is the big name. The one thing I’ve spotted about fake documents … is that they tend to be documents written about big names or by big names or to big names, because that’s the kind of document that document-collectors pay big money for. So it’s a big-name document.

“The next thing is, the wording contained within the document does not conform with German civil-service standards, which were very strictly adhered to. It just says, ‘referring to your message, the answer is as follows.’ German civil service would require that document to say, ‘referring to your message, register-number so and so, 12345, dated January the 10th 1943, the answer is as follows.’ But there is neither a register-number or a date on the document.

“Also, the document has got the highest possible security-classification, geheime Reichssache, and it’s only one of three documents in all the hundreds of thousands of decodes that I’ve read that has that top-secret classification.

“So, we’ve got those minor problems dealing it, and another very, uh, slightly lesser problem is that the totals don’t add up. There’s a digit wrong. So you’ve got a slightly awkward problem. Then you’re left with the nagging suspicion, that is it a coincidence that the seven-digit figure it gives as the grand total is identical to the grand total given in a document called the Korherr document?” (1:47:46 – 1:49:31)

Elsewhere (A Radical’s Diary, 4 October 2007) Irving also points out that the item was “bound into the archive file out of page-sequence” and that it has Reinhardt misspelled.

The strongest point in Irving’s litany of reasons for rejecting the Hoefle document is his observation that the item in several ways “does not conform with German civil-service standards, which were very strictly adhered to.” That alone should suffice to brand the item as a crude forgery. So it seems to this non-expert, at least.

Irving's doubts led him in June 2011 to propose that the document be subjected to forensic tests. He had “an acid exchange” with Stephen Tyas about this. Irving observed:

“He seems very keen that there should not be forensic tests on the Höfle document, or am I imagining that?” (D. Irving, A Radical’s Diary, 11 June 2011)

The next month Irving examines an ostensibly contemporary document referring to the Höfle document, and writes:

“It does seem to clinch the matter of whether the Höfle document is authentic or not, always assuming that this second reference document is not also a fake; but I think that unlikely. My brief examination of the latter document — its paper, other pages, typewriter-face, and pencil jottings on it — strongly suggests that it is contemporary with the other documents in that file.” (D. Irving, A Radical’s Diary, 20 July 2011)

If, however, the Hoefle Telegram is merely an altered document rather than an entirely fake document, that would explain why other documents seem to refer to it.

Someone will ask why anyone would bother to produce a fake document that still does not prove anything. There are possible motives. Suppose that the real telegram from Hermann Hoefle was not addressed to Adolf Eichmann but to the statistician Richard Korherr, who was never accused of any crime. The assumptions about what the message means would be entirely different. Eichmann's name as recipient of the message stimulates the Holocaustian imagination and activates circular reasoning, so that the document is seen as evidence for what is really only assumed to have happened.

Perhaps the Stand for Treblinka was altered. The numbers in the Hoefle Telegram can be made to tally if one assumes that the Stand for Treblinka is supposed to have a 5 on the end that was dropped, but Michael Mills points out that this adjustment makes the proposition that Jews were being mistreated at Treblinka seem farfetched, given the small garrison at that camp. This may be what Irving means by a “very, uh, slightly lesser problem,” since Irving wants to say that Jews were being robbed and killed in all the Operation Reinhardt camps.

On the other hand, maybe the dropped 5 and other anomalies are due to imperfect radio-reception. But, even assuming that the Hoefle Telegram is entirely genuine, it still does not prove what it is supposed to prove.

(6)

The Korherr Report is, for the most part, about the departure of Jews from Europe, and, for the most part, impossible to interpret as being about killing Jews. Korherr’s account of the Final Solution of the Jewish problem begins long before any program of mass-murder is supposed to have begun:

“Jewish emigration from Germany since 1933, in a way a restoration of the migration interrupted in 1870, aroused the special attention of the entire civilized world, especially the Jewish-ruled democratic countries.

[…]

“Altogether European Jewry since 1933, thus in the first decade of the unfolding of National-Socialist German rule, seems to have lost almost half of its population.” (Korherr Report)

Irving summarizes the Korherr Report as saying that only 4 million Jews were left in Europe and that 1.24 million (a misquotation of Korherr’s figure, 1,274,166 Jews) were sent to the camps in occupied Poland for “special treatment” (Sonderbehandlung). How does David Irving want us to interpret that word? By guessing:

“Well you don’t have to be a rocket-scientist to guess what that word means.” (1:50:10-14)

If we are supposed to “guess” that a million or so Jews were killed in the Reinhardt camps, it should be a guess that at least makes some kind of sense. How would it have made sense, when by Korherr’s account there were 17 million Jews in the world, and about half of those that were still in Europe ten years previously had left, to kill gratuitously some, but not all, of the Jews that had not yet left? Are the Germans supposed to have expended resources transporting Jews beyond the boundaries of the Reich only to kill them rather than resettle them, even though the Jewish problem had already been largely solved through emigration?

A “guess” like that would only make sense based on the premise offered by Anglo-American war-propaganda, that the rulers of Germany were criminal lunatics.

Irving invokes a kind of Hollywood gangster-movie interpretation of how things worked in National-Socialist Germany. Hollywood gangsters speak to each other in sinister euphemisms like “the garbage business,” “going to the mattresses,” and “an offer he can’t refuse.” Sonderbehandlung is supposed to be a word said with a sinister wink, like a gangster’s euphemism.

Korherr himself wrote a letter that appeared in the July 1977 issue of Der Spiegel wherein he stated that Sonderbehandlung did not mean anything sinister. Irving testified about Korherr’s complaint in 1988:

“He wrote a very long letter, as I understand it, to the German news magazine, Der Spiegel, a very irritated letter saying he’s fed up with his report always being adduced as evidence that there was a mass murder of the Jews. The report that he wrote was quite a straightforward statistical report and at no stage in his report had he referred to the mass killing of large numbers of Jews …” (David Irving, Toronto 1988)

But David Irving in 2009 ignores Korherr’s complaint.

Irving says that it is puzzling that the Korherr Report does not reckon Auschwitz together with the Operation Reinhardt camps, if Auschwitz was a killing-center. This observation is supposed to support implicitly Irving’s current position that The Reinhardt camps were systematic killing-centers and Auschwitz not.

The obvious reason why Auschwitz was not reckoned with the Reinhardt camps is that the Korherr Report is about deporting Jews. Auschwitz is in Upper Silesia, which at that time was part of Germany, which means that Jews sent to Auschwitz had not yet been deported. The Reinhardt camps however were in the General Gouvernement, near its eastern boundary. Jews sent to the Reinhardt camps were being deported, whereas Jews sent to Auschwitz were not.

(7)

To reinforce the fantasy that Sonderbehandlung has a sinister meaning, Irving claims that Himmler wrote a letter asking Korherr very nicely to replace the word Sonderbehandlung (special treatment) with other words:

“And Himmler didn’t like it. Himmler wrote back to Korherr the statistician at the time – and I was the one who found these letters – and Himmler says: ‘Dr. Korherr, excellent report, well written, a bit too long though. You’ve got to remember, this report’s going to be shown to Adolf Hitler, the Fuehrer. I want you to write a short version. Oh, and that sentence where you say the 1.24 million were subjected to special treatment, I want you to reword that. The 1.24 million were sent through camps in occupied Poland to the east.’ Somebody’s having the wool pulled over their eyes.” (1:50:14 – 1:50:45)

Irving says that he himself discovered that letter, but surprisingly neither an image of the letter nor the text of it appears on his website, although it can be found elsewhere online.

Irving’s representation of that letter is quite loose. In the first place, although Irving says that Himmler wrote the letter, it was in fact written by a member of Himmler’s staff, Rudolf Brandt, an attorney. Furthermore, the letter is entirely cold and impersonal. It contains none of the explanation and certainly none of the cajoling flattery that Irving portrays Himmler addressing to Korherr. Contrary to what Irving says, it contains no mention of Hitler. It is nothing more than a curt bureaucratic instruction about how some of the wording in Korherr’s statistical report must be changed.

Why does Irving say that Himmler wrote the letter when it was really written by Brandt on Himmler’s behalf? Most likely because it gives a greater credibility to the imputation that Himmler was trying to hide something if he handled the matter himself.

The lack of formality with which Irving portrays Himmler addressing Korherr is also perhaps more compatible with the crazy scenario that Irving wants to portray, wherein some officers under Himmler’s command are supposed to have undertaken, at their own whim, the project of mass-murdering Jews, while others did not. As improbable as that picture is in itself, formality and discipline do not harmonize well with it.

(8)

Irving refers to an alleged set of memoirs, supposedly written by Adolf Eichmann, that was handed to him “in a brown paper parcel” in (October) 1991 when he happened to be in Buenos Aires (1:52:20 – 1:55:25).

Here, Irving says that the man who gave him the alleged memoirs was “a man of Flemish origin” who was “close to a friend of Adolf Eichmann” (1:52:41 – 48). On Irving’s own website, however, several sources tell a different story. Irving quotes himself as telling a journalist for The Observer in early 1992 that the man who supplied the alleged memoirs was “a mutual friend” of David Irving’s and the Eichmann family’s. Irving has now backed away from claiming that this man knew Eichmann’s family at all, which makes the authenticity of these alleged Eichmann memoirs seem much less certain.

The explanation for why this third party would have Eichmann’s memoirs is not very convincing. Supposedly Eichmann's family worried about being “raided” again after Eichmann had been illegally abducted and taken to Israel by Mossad in defiance of the Argentine government in 1960, and therefore, it is said, gave the memoirs to a friend who then gave them to this Flemish stranger. (1:53:00 – 19)

A news-report from January 1992 has Wilhelm Lenz of the German Federal Archives saying that initial examination of the alleged Eichmann memoirs indicated that they were authentic. But the same report quotes Tuvia Friedman, contradicting Lenz:

“I believe this is the same manuscript made in the 1950s by the German journalist Zossen.” (AP, 14 January 1992)

Journalist Ron Rosenbaum, who interviewed Irving for his book Explaining Hitler, mentions that Irving cites the German Federal Archives at Koblenz as attesting to the authenticity of the alleged Eichmann memoirs, but responds as follows:

“This is only partially true. A spokesman at the Koblenz archives told my researcher that the ‘memoirs’ appear to be cobbled together from interviews with Eichmann by a sympathetic journalist and other sources.” (Rosenbaum, Explaining Hitler (updated edition), p. 224)

The "sympathetic journalist" would be Zossen (whose article Eichmann in fact denounced as inaccurate during his trial). And the “other sources”? It makes little difference. A so-called memoir that is cobbled together from a journalist’s interview and other sources is almost certainly the work of persons other than the alleged author.

The most puzzling thing about Irving’s account is why the man who presented Irving with the supposed memoirs of Adolf Eichmann attesting to an order from Adolf Hitler to start killing Jews did not try to claim the £1000 reward that Irving had been offering for such evidence since 1977. Irving gives no indication that the man asked for his reward.

Irving says that it was “good luck” to receive those alleged Eichmann memoirs out of the blue, but my suspicion is that Irving was used as a conduit for political propaganda, in this instance and in the case of the “Goebbels Diaries” that lay conveniently waiting for him in Soviet state archives during the same period. These “Eichmann memoirs” contain references to an order from Adolf Hitler to start killing Jews, and also gassing vans. That was the poison in this bait offered to David Irving.

Irving however finds a way to have his cake and eat it too. He accepts the reference to gassing-vans in these memoirs, but rejects the claim in the same memoirs that Hitler ordered the mass-killing of Jews. Irving rationalizes this picking-and-choosing by assuming that Eichmann presciently lied about Hitler in his memoirs so as to create an alibi for himself in anticipation of being kidnapped and put on trial.

Even assuming that Irving is correct about that, one must wonder why the alleged Eichmann memoirs were not revealed at the time of Eichmann’s trial. Keeping them secret negated their purpose, if the purpose was to create an alibi for Eichmann at his anticipated trial.

Irving's argument against the claim that Hitler ordered the Holocaust very easily mutates into an argument against the Holocaust itself. Combined with other information that David Irving supplies, it becomes exactly that:

“Clearly if such an order existed you would expect to find it on paper. You would have expected the British to have decoded it somewhere. You would expect somebody to have written a letter home to their mother saying, ‘Dear Mummy, I have today had to transmit the most terrible order to the SS-Gruppenfuehrers on the Eastern Front.’ This kind of thing.” ( 1:54:30-1:54:57)

Certainly David Irving is correct to say that there would be a written record of it, if Adolf Hitler had ordered the systematic killing of Jews, but not only for the reason that Irving gives, that it is difficult to conceal such things: also because any military officer asked to undertake such enormities would have wanted a written record of the order so that he could defend himself if the action became a matter of controversy. Irving himself indicates this with his discussion of Deckungsschreiben, wherein he says that German officers wanted documentation of orders. We also have Albert Speer’s rebuke that systematic killing of Jews could not take place without Hitler’s knowledge, which means not without Hitler’s order:

“To make such a claim shows a profound ignorance of the nature of Hitler’s Germany, in which nothing of any magnitude happened, or could conceivably happen, without his knowledge.” (Albert Speer, letter to Gitta Sereny, late 1977)

Therefore, the lack of any contemporary written record of an order from Adolf Hitler for systematic killing of Jews really means that no such action was undertaken.

The Rumbula Massacre (1:57:45 – 2:01:38)

David Irving’s mention of his bizarre theory that the Holocaust happened but without Hitler’s will or knowledge serves as a segué into discussion of the putative Rumbula Massacre (which Irving never calls by that name). The Rumbula Massacre is supposed to have been a mass-shooting, a few kilometers from Riga, of most of the Jews from the Riga ghetto. In early accounts the dates vary, but Irving takes 30 November as the date for the story that he tells.

The whole story of the Rumbula Massacre is doubtful, but so far little skeptical attention has been focused on it. Thomas Kues, who did write an article about it a few years ago, stated that “the Rumbula incidents … have hitherto received no attention from revisionist historians” (T. Kues, in Inconvenient History, Vol. 4, No. 4, 2012).

The relative lack of critical attention focused on this episode makes the Rumbula Massacre a convenient retreat for David Irving in his flight from Holocaust Revisionism.

* * *

Irving claims, without citing any source, that on 30 November 1941 Himmler suggested to Hitler that a trainload of Jews sent from Berlin to Riga be simply killed, since there was no place to house them. Hitler supposedly replies, “Out of the question.” Irving alleges that Himmler then had to reverse a plan that had already been set in motion, and phoned Reinhard Heydrich to tell him to cancel the killing of those Berlin Jews.

That is the context that Irving supplies for interpreting Himmler’s handwritten notes from a telephone conversation with Heydrich:

“Judentransport aus Berlin.

Keine Liquidierung.”

These notes seem to have been written by Himmler strictly as mnemonics for himself, and not to communicate anything to others. For that reason, they are extremely laconic and their meaning is not necessarily clear to anyone other than Himmler.

However: there are, before those two lines that David Irving likes to quote, two other lines. Lucy Dawidowicz takes all four lines together as a single coherent note:

“Verhaftung Dr. Jekelius

Angebl[ich] Sohn Molotows.

Judentransport aus Berlin.

keine Liquidierung.”

Dawidowicz understands this to mean that Dr. Jekelius, alleged to be the son of Molotov, is to be arrested, but not killed – unlike, she assumes, the rest of the transport. (Incidentally, Dawidowicz also says that the Judentransport is headed for Prague – where Heydrich is – and not Riga.) (L. Dawidowicz, The Holocaust and the Historians, p.38)

The premise of Dawidowicz’s interpretation is that all four sentence-fragments together form a coherent message, but this is doubtful.

In the first line, Dr. (Erwin) Jekelius is the name of a well known German medical doctor whom Paula Hitler was forbidden by her brother to marry, and who could not remotely be imagined to be the son of Molotov. It would be quite amazing if a putative son of Molotov also happened somehow to have the surname of this German physician. Therefore I conclude that the first and second lines, at least, do not represent parts of a coherent whole.

David Irving does not go as far as Dawidowicz in trying to unify all four sentence-fragments, but he does assume without justification that the act of Liquidierung in the last line has as its object the Judentransport in the penultimate line. There is no reason to assume this.

Furthermore, Liquidierung does not have to mean killing. A very common expression is: Liquidierung des Ghettos – which does not mean killing everyone in the ghetto, but merely relocating them. Himmler’s note could refer to a ghetto that was not to be dissolved at that time. Arthur Butz has suggested that it was the train itself that was not to be liquidated (A. Butz, 5 September 2008). David Irving’s interpretation of Himmler’s jottings is in any case highly doubtful.

It is also an interesting question, if Himmler wanted to countermand an imminent action in Riga, why he would have phoned Heydrich in Prague about it. It seems that he should instead have contacted Friedrich Jeckeln in Riga directly, given the urgent nature of the message. The paradox is all the more glaring, given that Himmler and Jeckeln were in direct communication already; Jeckeln had in fact contacted Himmler directly that morning. It is absurd to suppose, as Irving would have us suppose, that Himmler tried to stop what Jeckeln was doing that day in Riga by going through Heydrich in Prague. But there is that note from Himmler’s conversation with Heydrich that can be given a sinister connotation, and so Irving wants to work it into the story somehow.

There is also a chronological problem with the drama that Irving wants to construct around Himmler’s notes. Irving assumes that the telephone-call to Heydrich (at 1:30PM) resulted from an exchange between Himmler and Hitler, but, as Butz points out, the telephone-conversation happened before Himmler’s meeting (2:30-4:00PM) with Hitler that day.

There is no genuine evidence in this “Talking Frankly” video for Irving’s story that Himmler suggested to Hitler killing a thousand Berlin Jews and then tried to stop Jeckeln in Riga from doing it – much less that those thousand Berlin Jews were machinegunned, as Irving says, “along with 4000 local Jews from Riga” before the countermand was received.

* * *

Lacking good evidence, Irving uses innuendo to generate the belief that those Jews were machinegunned.

Irving refers to the fact that Jeckeln, in his urgent request to Himmler on the morning of 30 November 1941 for more Suomi submachineguns, uses the word Sonderaktionen. Irving tells us that Sonderaktionen means “killing operations,” but this is not at all evident. It is clear, in fact, that a Sonderaktion does not have to involve killing anyone.

It can designate a mass-arrest. When 184 members of the Jagiellonian University of Krakow were arrested on 6 November 1939, the mass-arrest went by the codename Sonderaktion Krakau. In that Sonderaktion, nobody was killed. Jeckeln’s Sonderaktionen, if they were like the one in Krakow, involved rounding up suspected or anticipated troublemakers for preventive detention.

Irving also tries to make the request for submachineguns itself seem sinister. He inaccurately calls them tommyguns to evoke the cinematic association of that word with gangsters:

“You know, like James Cagney, you know, in the movies: tommyguns with the drum-magazines. And the Suomi magazine tommygun was ideal for the killing-operations.” (1:58:58 – 1:59:07)

David Irving may be unaware that anyone other than criminals ever used the Thompson submachinegun. The FBI used them, and even United States Marines.

The utility of submachineguns for Sonderaktionen, meaning mass-arrests, is clear. The weapon’s firepower offers a great intimidation-factor for keeping a recalcitrant crowd under control. The bullet from a submachinegun, issuing from a pistol-cartridge, has low range and relatively little penetrating power, which is desirable in an urban environment, to minimize the danger of killing innocent bystanders.

* * *

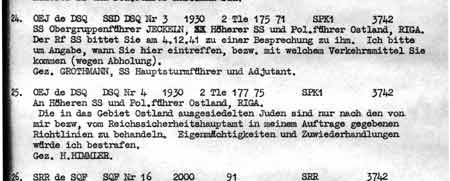

Irving creates the false impression that Himmler referred specifically to the killing of those Berlin Jews:

“Himmler says, ‘The operation you carried out in Riga grossly violates the guidelines laid down by me and Heydrich. Any such further excesses will be ruthlessly punished. You are to report to headquarters.’

“He’s referring to the killing of the Berlin Jews and the local Jews.” (1:59:14-28)

There is no document that Irving cites that really says this. Irving is misrepresenting.

In addition to attributing fictitious statements to Himmler, Irving has misstated the date of the message. Irving says that Himmler’s message to Jeckeln about guidelines was sent on 30 November 1941, but in fact it was sent on 1 December. Mark Weber confirms that the relevant message was sent on 1 December, and comments on Irving’s use of it as follows:

“Particularly noteworthy was a Dec. 1, 1941, order by Heinrich Himmler that, Irving said, apparently was issued following a stern rebuke by Hitler because of an unauthorized mass shooting of Jews the day before near Riga, Latvia, including several hundred Jews who had just arrived by train from Germany.” (M. Weber, JHR, September/December 2001)

Irving moves the message forward to 30 November, the same day as the alleged shooting, probably to make it seem more urgent. If it was sent the day after the alleged shooting then it seems less urgent. In fact it was not an urgent message. It does not even say, as Irving alleges, that Jeckeln did anything wrong. It says nothing about any operation carried out in Riga. Not a word.

Also, Himmler does not say that he will punish anyone. He says that he would punish (würde ich bestrafen). The use of the imperfect subjunctive implies that no act requiring punishment has yet occurred, or in any case that Himmler himself is not presently intent on punishing anyone.

“25: OEJ from DSQ SSD DSQ No 4 1930 2 parts 177 75 SPK1 3742

To Senior SS and Police Commander, Ostland [Baltic Provinces], RIGA [SS Obergruppenführer JECKELN].

The Jews resettled in the Ostland region are to be treated only in accordance with the guidelines laid down by myself or by the Reich Security Main Office. I would punish those who act on their own authority or in contravention .

(Sgd. H HIMMLER)”

Note Weber’s indulgent words: “Irving said, apparently.” What it really means is that the “stern rebuke by Hitler” is something that Irving invented to create an interesting story. The fact that the “stern rebuke” is a product of speculation is evident from how Irving presents it in Hitler’s War:

“Somebody – and this can only have been Hitler himself – had reprimanded Himmler…” (D. Irving, Hitler’s War (web edit), p. 456)

Irving does not really know that this happened. It is a product of imagination.

Incidentally, David Irving told the same story to the court during his libel-suit in 2000. Irving told the court that Himmler’s message to Jeckeln said “explicitly” something that it does not say at all:

“But we know from the late 1941 police decodes … precisely what orders had gone from Hitler’s headquarters, radioed by Himmler himself, to the mass murderer SS Obergruppenführer Friedrich Jeckeln, stating explicitly that these killings exceeded the authority that he, Himmler, himself had given, and by the Reichssicherheitshauptamt….” (“David Irving’s Final Address in the London Libel Trial,” JHR, March/April 2000)

If he would say it in court then perhaps Irving believes his own imaginings.

Since we know that German personnel under Hitler’s government who mistreated Jews on their own initiative were punished, it is inconceivable that Jeckeln could have conducted the alleged Rumbula Massacre and gone without being punished. Jeckeln did confess to crimes in a show-trial put on by the Soviet Union in 1946, but obviously this is no indication of what really happened.

* * *

To add the appearance of substance to his account of the Rumbula Massacre, Irving cites the statement tortured out of Walter Bruns, a prisoner of the London Cage who, according to CSDIC's document, is supposed to have been an eyewitness to the massacre.

An important indication of the untrustworthiness of this statement is that Bruns told a substantially different story when put on trial: at Nuremberg, Bruns testified that he had not witnessed the shooting himself; rather he had heard an oral report about it from two subordinate officers that he was (strangely) unable to identify. (G. Fleming, Hitler and the Final Solution, 1987, p.83)

Irving however, without mentioning this discrepancy, emphasizes the premise that Bruns himself had witnessed the shooting, which obviously makes the story seem more credible:

“In fact on that very day, November the 30th, there is a German army colonel who hears what’s happening to the Jews, outside the town, and he’s lost all his Jews that day, and he’s wondering where his Jewish workers have gone. The local SS guy says, ‘Well if you want to know what’s happening to your Jewish friends, you’d better drive out of town down the road to Dueneberg, to Dvinsk, about eight kilometers and you’ll see what’s happening to your lovely Jews.

“And the colonel, he describes in April 1945 to a prisoner in a British prison-camp, here, near here in Latimer, and he says, ‘So I drove down the road, and there was this open field, and three, two or three pits had been dug out, and truckloads of Jews were being driven up and made to lie down in the pits, sardine-fashion, and they were being machine-gunned to death by these men standing on the rim.

“And the fellow prisoner says, ‘But Herr General’ – because he’s a general now – ‘Herr General, what were the gunners saying? Were they saying anything when they were doing this?’ ‘Oh, yes, all these coarse remarks, these coarse shouts going around. I remember one of them shouting, ‘Look at that one. Look at that beauty.’ And I can see her in my mind’s eye now, a beautiful girl in a flame-red dress.

“And that’s that day, November the 30th, 1941.

“And he says, ‘We discussed it among ourselves, army-officers. Somebody had to tell the Fuehrer, Adolf Hitler, what was going on. None of us wanted to be the one. So we sent for a leftenant and told him to come out later that day, see what was going on and write a report. And we sent his report up to Hitler’s headquarters.’ And that evening the order came that this kind of shooting had to stop immediately, forthwith. From Hitler’s headquarters.” (2:00:02 – 2:01:32)

First: does it make any sense that Jews needed by the German army for work were being taken away by the SS and killed? Not a bit.

The account of the Germans’ behaving like licentious and undisciplined thugs (as conveyed through the description of their banter) is typical war-propaganda, but of course not an accurate representation of how German personnel really did behave. Bruns’ actual statement goes farther in this direction than Irving lets on, alleging that “at Riga they first slept with them [Jewish women] and then shot them to prevent them from talking.” This is really over the top. It is inconceivable that it could have become a common occurrence and common knowledge that SS-men or police under the SS were sleeping with Jewish women and then killing them at their own discretion. They would not have lasted long.

David Irving’s version of Bruns’ account has Hitler being informed by some Wehrmacht officers of what happened, yet there are no negative consequences, neither for Friedrich Jeckeln nor for Heinrich Himmler. If Irving is going to endorse the story of the Rumbula Massacre, including Walter Bruns’ confession, then he is going to have to say that Hitler knew that it happened but punished nobody.

David Irving chooses not to mention that Bruns’ account says that Hitler ordered the Rumbula Massacre. Bruns even says (conveniently) that the written order was shown to him. The purpose of making Bruns tell this story, then, was not only to confirm a story of German atrocities but to pin the blame on Hitler. But you would not know this from Irving’s presentation because he leaves it out.

Bruns’ narrative undermines itself with its own surreality. It says that the Jews “stood in a queue 1½ kilometers long which approached step by step – a queueing up for death.” Certainly, this is over the top. Obviously, Jews in such numbers, under such circumstances, would not have stayed in a queue. No wonder that Irving, trying to preserve Bruns’ credibility, decided to leave it out.

There is also a discrepancy between Bruns’ account of the victims’ being machinegunned (by which I understand automatic fire), and other accounts which say that the “Jeckeln system” of mass-shooting was accomplished with a single bullet to the neck. The latter seems to be the prevalent version of the story.