Manny Steinberg’s Outcry

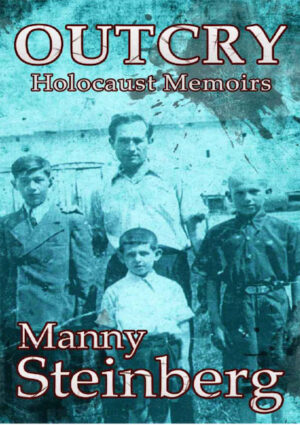

Welcome back dear readers for our next inquiry into a Holocaust memoir. Today’s guest is Manny Steinberg and his memoir is Outcry: Holocaust Memoirs (Amsterdam Publishers, 2015). Approaching 1,400 reviews with 81% rating it five stars on Amazon, this merits a look.

Welcome back dear readers for our next inquiry into a Holocaust memoir. Today’s guest is Manny Steinberg and his memoir is Outcry: Holocaust Memoirs (Amsterdam Publishers, 2015). Approaching 1,400 reviews with 81% rating it five stars on Amazon, this merits a look.

Mendel “Manny” Steinberg was born in 1925 in Radom, Poland. In 1942 his ghetto was liquidated and he spent the rest of the war years in various camps including Auschwitz, Vaihingen and Neckagerach. After liberation he moved to America in 1946 along with his father and brother.

Before we move on with the content, two things should be pointed out. First, Steinberg begins with this declaration:

“The following pages recount my real-life experiences and memories, but the names in my story have all been fictionalized.” (p. 2)

Usually this is for privacy protection, although he does not explain why it is needed, or if there is some other reason.

Second, there are problems with the chronology as given. Born in 1925, Steinberg would have been 16-17 years old in 1942. He mentions this year of his first deportation as follows:

“Our miserable existence in the Ghetto ended in June of 1942.” (p. 63)

But after this he claims several times that he was 14 years old. Later he writes:

“Three long years had been spent in this prison camp and now I was to leave it, destination unknown. I had reached the age of seventeen, and although I would have still been considered a boy, the experience of living through this hell had aged me considerably.” (p. 94)

So we arrive at 1945 and yet after a few pages we read the following:

“After several days, we finally reached our mysterious destination. It was Auschwitz, the most infamous of the concentration camps. Here the gas chambers were said to work day and night to keep up with the mass murdering.” (p. 100)

This is impossible as the camp had been evacuated in January of that year. If Steinberg was indeed 17 when he was sent to Auschwitz, this was in 1942 and he could not have spent 3 years in the first camp (near Radom) as he claims. The confusion continues with one last remark:

“I was nineteen years of age and in many ways still a boy.” (p. 164)

This after he moved to New York in 1946, when he was 21 years old. So it seems that at least Steinberg has not reconciled his dates/ages. Anyway, let’s see what he has to say on the extermination story.

The first time he hears about it is as follows:

“Some of the Polish men working on the trains were in sympathy with the Jews and passed on information. They told of how a chemical that smelled like chlorine would be sprinkled inside the cars. When the prisoners urinated, a deadly gas would form, suffocating them to death.” (p. 74)

This is the story of the “trains of death” made known by Jan Karski,[1] which was nothing but propaganda and today has vanished from history, although Karski himself still appears here and there.

After this, Steinberg heard from a friend that his mother and his youngest brother had been killed at Treblinka. When he asked for proof his friend told him what he had learned from another friend working on the railroads. The train had gone to Treblinka, where only 40% of the people arrive alive to be delivered “to the gas chambers and crematorium” (p. 75). In short, the proof came from the information of a friend, of a friend, of a friend…

So, what was Steinberg’s own experience?

“At the gate to Auschwitz was a group of German doctors. They were wearing white aprons spotted with blood. They resembled butchers, and that is exactly what they were. Only the meat was now human instead of animal. I watched their bloody hands and thought of the Jewish people they had tortured, killed, mutilated and experimented on. They had no feelings about us. We were just another group of Jews to be sorted. The young separated from the old, the well from the sick. Then another gas lever to be pulled for the unfortunate ones selected to die.” (p. 100)

Doctors with aprons stained by blood at the selections remind one more of a horror film, not to mention that such a detail would not have gone unnoticed by others. Even Elie Wiesel with his geysers-of-blood stories never wrote anything quite like that. Steinberg continues in the next paragraph:

“We were told to remove our clothes and put them in a pile at our feet so that a physical examination could be carried out. I heard someone be addressed as Dr. Mengele and knew that this was the end.”

Clothing removal during the selections is also unheard-of. Furthermore if Steinberg was deported in 1942 he could not have seen Mengele who was at Birkenau after May 1943. But Steinberg gives even more fanciful details. After the selection, in order to drown the cries of those selected to die, a group of naked (!) Gypsy women banged on drums (p. 101)! And here’s what followed:

“For the first time I saw the tall chimneys with the reddish smoke billowing out from the top. They were the crematoriums. As soon as people arrived in the cattle cars, they were taken to the gas chambers. Older people that were too weak to walk or young children who had not learned to walk yet were thrown onto trucks with hydraulic lifts. The trucks would drive over to the crematorium, reverse up to it, and then use the hydraulic lift to make the people slide to a fiery death. Prisoners were given a piece of soap and told that we could take a bath if we wanted. This would have been a great treat, but of course we were afraid. We knew that this had been used to lure people into the gas chambers. On the soap were the letters ‘RJF’. The ‘R’ was for ‘Rein’, German for pure. The ‘J’ for ‘Jew’ and the ‘F’ for ‘Fett’, German for flesh.” (p. 102)

He also adds that he had the task of removing the gold teeth from the dead as well as cutting the hair of the women killed but stops right there without further details.

Anyway, after these “questionable” statements, here is something more believable. It’s January 1945 and Steinberg is in another prison camp:

“One day a group of German officers arrived in the camp and began making a special selection of prisoners. We were given a medical examination and I was one among some six hundred who were loaded onto trucks and hauled away. As usual, we had no idea where we were going. One thing I did know: we were all sick. Some of us were skeletons, others had an unhealthy bloated appearance, but all were undernourished and in rags. We were a sad sight. We were all sure that we were on the way to be exterminated at last. What else were we good for? We said our goodbyes to each other and waited for the ordeal to be over. Just let this death sentence be quick, I prayed. During this trip, we talked about what we had done before the war, where we had lived, about our families and our lives before we had been forced into concentration camps. Each person talking in their own language, with everyone’s words intermingling. We all held hands and there was much sobbing. Suddenly the long line of trucks came to an abrupt halt. I tried to peek under the canvas to see where our journey had ended.” (p. 130)

Thinking that the gas chamber was waiting for him, he hesitated. But:

“The canvas cover was taken off the truck. My heart was beating very fast. I clasped the hand of the prisoner next to me and tearfully said goodbye. As my eyes adjusted to the light my mouth dropped open at the sight before me. Stretchers! A long line of stretchers with men waiting to help us! My God! Could this really be true? Was help here at last? Immediately I was lifted, yes lifted, off the truck, placed on a stretcher, covered with a blanket; a warm blanket and taken to wooden barracks that were set up as part of a recuperation center. As we moved along, I realized that I would be given medical help, perhaps more food, that I now had the chance to live. I thanked God silently. As I was carried into the barracks, my eyes caught sight of the supplies and equipment intended for us. There were rows of bunks, and in each bunk was an occupant covered with their very own blanket. There were windows, it was clean and attendants were waiting on the prisoners. I closed my eyes for a minute and thought perhaps I had died and gone to heaven. The feeling of a real blanket over my body, the first one in five years, gave me a sense of real luxury. I snuggled into it and tears of joy ran down my face. A little human kindness after all the years of cruel treatment. This was more than I could stand without giving way to my feelings. For the first time in all these long and torturous years I felt safe; all was well and I would survive. The danger of extermination and fear vanished. Surely they would not go to the trouble of getting me well and then exterminate me. My chances of survival seemed better than at any other time. A feeling of great happiness came to me and I slept.” (p. 131)

Summary

Books like this are praised to the skies and offered all the time as evidence of the Holocaust. And yet a simple reading of them reveals passages that would make any historian run away. The single fact that in 2015 the soap story is still offered as eyewitness testimony without even an editor’s comment, proves the total bankruptcy of the Holocaust story.

Editor’s note: Amsterdam Publishers, a self-proclaimed “Specialist in Holocaust memoirs,” is not a publisher in the traditional sense; it is a provider of publishing services to authors publishing their own works, their website explains. Before the advent of the Internet, such operations were called “vanity publishers.” Instead of paying their authors, their authors pay them. In this case, they even offer ghost-writing services by “various of [their] authors.” It evidently is quite a lucrative business.

[1] Theodore J. O’Keefe, “A Fake Eyewitness to Mass Murder at Belzec“, The Revisionist, No. 1, Nov. 1999, CODOH series; https://codoh.com/library/document/a-fake-eyewitness-to-mass-murder-at-belzec/

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 2018, Vol. 10, No. 2

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a