On the Garaudy/Abbé Pierre Affair

Someone has passed on to me a comment by Jean Stevenin, a lawyer of the Paris bar: “This is a continuation of the Faurisson affair!” For him, at bottom, the Garaudy/Abbé Pierre affair is (as was the Roques affair or the Notin affair) a growth, a resurgence and a continuation of the Faurisson affair, which began in 1974 and exploded in late 1978.

I have noted the timidity, if not quasi-silence, of our journalists on the subject of the gas chambers. All should have denounced, on the spot, Garaudy's profound skepticism on this matter. But such is precisely the characteristic of the taboo: those who have a mission to preserve it dare not even reveal that it has been profaned. Having penetrated into the holy of holies, Garaudy had discovered that the tabernacle supposedly containing the magic gas chamber was empty. But mum's the word!

An article in Le Point (April 27, 1996, pp. 54-55) shows that the writer has a rather good knowledge of revisionism. It reproduces a fragment of my initial news release on the Garaudy/Abbé Pierre affair (April 19):

It is necessary to call a spade a spade: this genocide and these gas chambers are a fraud. If I were Jewish, I would be ashamed at the thought that, during more than half a century, so many Jews have propagated or have allowed to be propagated such an imposture.

Le Point dropped the eight final words of my text: ” … such an imposture, underwritten by the major media throughout the world.”

Elsewhere in the article the revisionists are described as forming a “minuscule yet stubborn sect.” While the adjectives “minuscule” and “stubborn” certainly apply, the word “sect” is improper because in this case there is no religious belief nor spiritual guide. In France, the number of active revisionists has been minuscule: ten have undertaken and successfully pursued researches and 20 others have dedicated a part of their lives and their means to the support of the ten. The number of revisionists of conviction who have refrained from any involvement amounts to several hundred, while thousands of sympathizers have watched from the sidelines.

How is it that a handful of men and women succeeded in breaking a leaden silence imposed the world over by the richest, the most powerful, the most influential and most feared human group in the West? This group is the Jews. Actually, what did any of us matter compared to Edgar Bronfman alone, the super-rich emperor of alcohol, and president of the World Jewish Congress, who has said that there is no task more urgent than to put an end to revisionism?

The disparity between their strength and our weakness I personally assessed at Oxford in July 1988, on the occasion of one of the most impressive international colloquiums ever organized against revisionism. Its instigator was the billionaire crook Ludvik (or Lajbi) Hoch, alias Robert Maxwell. To undermine this gargantuan enterprise, there were two of us (I repeat: just two): a Frenchman and a Frenchwoman, attended by two other French persons acting with greater caution.

Nevertheless, the participants very quickly felt themselves under a state of siege. Several audacious and rapid actions brought to bear upon the nerve centers of this colloquium derailed the event for the invited guests motoring about in chauffeured Bentleys and lodged in luxury hotels. The British police were on the look-out, but how could they imagine that only two determined individuals, and with so little material and financial resources, were behind an operation with such an impact? By the close of the colloquium, Robert Maxwell, now at the end of his tether, penned an article of vengeance against the British journalists, accusing them of not having accorded the event its proper importance. The title of the article, which appeared in one of newspapers of his publishing empire, was Emile Zola's famous challenge: “J'accuse!”

In these closing days of April 1996, the Garaudy/Abbé Pierre affair is running at full speed. It does not appear ready to subside, even if the two principal parties are trying to distance themselves from revisionism. The Holocaust lobby never forgives the least infraction against its taboo. Excuses, retractions, explanations and flatteries will not assuage the offense against them. They will be without pity. They will flail all the harder at those who, even for a moment, cringe or offer their backsides.

The Garaudy/Abbé Pierre affair makes me both happy and bitter.

I am happy because those who are deeply involved in all this are now finally taking to heart what I've nearly killed myself repeating for almost a quarter century. In late 1995, when I saw that revisionism was making inroads on the Internet, and that Jewish organizations were calling for its censorship, I felt some sense of relief. As the exterminationist historian Jean-Pierre Azéma might put it in his particular manner of speaking: “For Faurisson it's like eating cake, and for Abbé Pierre, consecrated bread.”

This happiness is tinged with some bitterness because, over the past 22 years, these people and their comrades had either insulted me or allowed me to fight alone, or nearly alone. Here again, one might paraphrase Azéma's style: “Faurisson has done, he alone, all the work. For this he has taken plenty of gruff and for nary a brass farthing. Today, they are starting to go through his pockets all the while insulting him.” For my part, I would add that these eleventh-hour laborers, men such as Garaudy and Abbé Pierre, are also engaging in an excessive show of anti-Nazism. What temerity on their part!

One shudders for them over this.

At the conclusion of his television program, Bernard Pivot asks the authors he's invited to appear as guests about their literary preferences, their tastes on all sorts of matters, and then, to wrap up, he solicits their imagination: “If God were to exist, what would you like him to say to you?”

Pivot, whose past and present comportment reveals his trepidation regarding the International League Against Racism and Anti-Semitism (LICRA), is someone who would certainly never invite me to appear on his program. But, just for the heck of it, let us imagine that he does. Here is how I would answer him:

Your questions about my tastes are indiscreet. I will not divulge in public that which resides in the domain of the intimate. Yet the atheist that I am replies to your final question: “I would like God to tell me: here, up above, it is not like it is on earth, and it is certainly not like it is at Bernard Pivot's. Here reigns freedom of expression.”

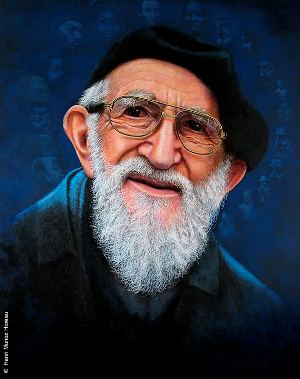

“The gas chambers did exist.” This 1986 French editorial cartoon draws parallels between the forced recantation of Galileo Galilei in the 17th century, and the pressure by authorities in our own era to compel doubters of the orthodox Holocaust story to submit to official dogma. It was drawn by Laurant Fabre (“Konk”), who was expelled from the prestigious Paris daily Le Monde for his nonconformism. Ten years later, it seems to describe Abbé Pierre's predicament.

Through this response I would thus simultaneously confirm that for me, God, our individual survival and the kingdom of freedom of expression are nothing but dreams.

People often ask me about my political views. It is pointless and, unfortunately, typically French. In France, everything oozes politics. How would my political opinions provide support either for the dogma of the existence of the gas chambers or the thesis of their non-existence? Whether I am of the right or the left, philo-Semite or anti-Semite, how could this give rise to a Nazi gas chamber at Auschwitz where there never was one?

During my long wait for this small bit of happiness, tinged with bitterness, I believe I can truly say that I voyaged through hell. I first knew total solitude, before the arrival of a few friends who, for the most part, have remained faithful. At the same time, though, I have also had to defend myself against many of these same friends, who overwhelmed me with their advice and sagacity.

I have lived for many years among friends who considered themselves more cunning than I. They radiated a sense of their own superior understanding of strategy, tactics, diplomacy and psychology. They explained to me the virtues of moderation or the prudence of handling people's minds; they knew how to do this in order to be convincing; they informed me that plain talk presented too many inconveniences, and that instead of stating plainly that the emperor has no clothes, it is better to give people, through subtle and round-about means, the suspicion that perhaps the emperor is not wearing magical garments, in which the crooks are pretending to have swaddled him.

They took the view that I was wrong to regard myself as fighting in a kind of boxing ring, where I knew how to effect only four or five movements and always the same: a right jab, a left jab, a left hook followed by a right hook and then, at the end of it all, a painful uppercut punch. For the few punches given, deftly it seemed to me, I received an avalanche in return, often below the belt, with the full assent of the referees. At the end of each match, more than once I found myself on the mat, groggy and nearly down for the count. Each time I picked myself back up. I tottered. I was declared beaten. Everywhere people were trumpeting that it was over and that one would never again see me in the ring. My friends thereupon offered me a profusion of advice for the future. They put forward the wisest of schemes, which consisted of avoiding any new encounter. Above all, no “Faurisson foolishness!”

I reproach these friends for not having openly proclaimed themselves as revisionists, and for not shouting from the roof-tops that gas chambers and genocide were but a lie, a calumny and a defamation. In France, I found myself alone in saying this and in repeating it publicly. Our adversaries had a field day denouncing a lone man. Considering the impact of a lone revisionist, I am persuaded that, in France at least, if even just a few other revisionists had openly proclaimed their convictions in the wake of the pitiful declaration by 34 historians appeared in Le Monde on February 21, 1979 (a declaration whose contents implicitly confirmed the non-existence of gas chambers) revisionism would have successfully broken out of its obscurity already in the early 1980s.

One day we shall indeed see the end of this seemingly interminable affair. I am putting everyone on notice: I will not change; even if my enemies keep up their intimidation and my friends continue to give their advice. Historical revisionism is an intellectual adventure that I shall endure to the end, and in the manner, good or bad, that I have chosen for myself.

– Mâcon, April 27, 1996

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 16, no. 4 (July/August 1997), pp. 26-28

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a