To Kill a Taboo

Review

Spotlight. Open Road Films, 2015, 129 mins.

The eternal enemy of truth—and history—is taboo. Taboo is the enveloping social process by which knowledge is contained by suppressing its expression. First among those subjected to taboo are the direct witnesses to the knowledge, and first among these are those who have suffered from it but survived in condition to render testimony. This winner of the 2016 Academy Award for Best Picture is about the breaking, initially in Boston, of a well-enforced taboo against publicly charging Catholic priests with molesting children of their parishioners, an offense whose commonplaceness vastly exceeded the assumptions of Catholics and non-Catholics alike. And this may have been the primary effect of the taboo: not the absolute concealment/denial of the offenses, but rather suppression of awareness of their pervasiveness.

Taboo disinforms history profoundly—always has and always will. This is why attack upon and defeat of taboo offers such enormous potential for the improvement of historical understanding and the dissemination thereof. George Orwell once wrote, “Journalism is printing what someone else does not want printed: everything else is public relations.” Analogously, revisionism is revealing what violates some taboo or other: everything else is … what? Nattering?

And taboos there are aplenty, but in the arena (yes, it is an arena) of history today, none looms larger than the bedrock of Jewish nationalism, the Holocaust. This review, then, will counterpose the destruction of the taboo against priestly pederasty in the first years of the present century with the efforts ever since World War II to overcome the global taboo against correcting the history underpinning the story everyone knows as the Holocaust. There are as many differences between these two as there are similarities; the differences can be quite as illuminating as the similarities.

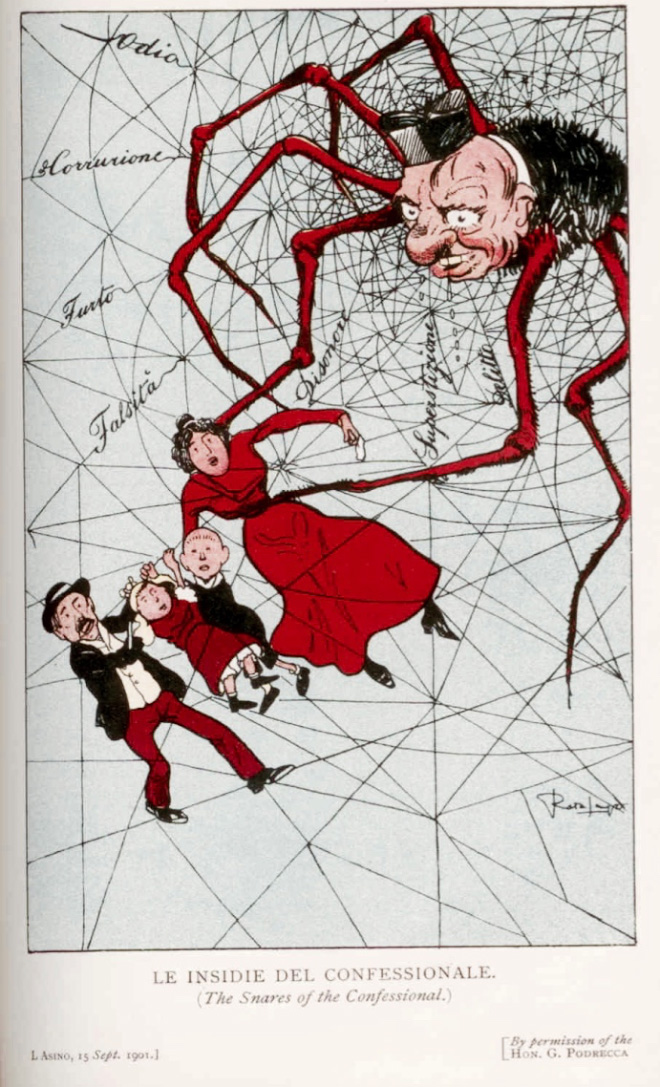

The most-salient point of comparison is indeed a difference: the assault on clerical concupiscence begun by the Boston Globe in 2001 has been won, hands-down, by the attackers of the taboo. The decades-long assault on the towering edifice of the Holocaust, on the other hand, today faces counter-assaults, legal, financial, reputational, and physical stiffer not only than they ever have been in the past, but more-draconian by far than any brought to light against the heroes of the film here reviewed. Indeed, to find doctrinal enforcement comparable to that imposed on Holocaust revisionists today, one has to go back to the times of the Inquisition, a project, ironically, of that very Catholic Church that plays the loser in the drama depicted in the film.

A point of similarity between the two dramas is that in both cases, the champions of the taboo are palpably aligned with specific religions. In the one case, it is the standing institution of the Catholic Church that opposed publication of the sins of its agents, while in the other it is the ubiquitous agency of worldwide Jewry that harbors the often-invisible defenders of the ramparts of Holocaustery. The Catholic Church has surrendered in the present drama, and is doing penance for its institutional sin of deception as it, above all others, knows how to do. At such time as the Holocaust taboo is defeated, more-likely with a whimper than with a bang, there will be no surrender, ever. Rather, in keeping with the character of the counter-insurgency thus far mounted, there will be the usual assortment of would-be victims shrugging, looking about innocently and intoning, “Who, me?”

Compared with the offensive “defense” offered by the advocates of Jewish victimhood, the defense of the Catholic Church was utterly passive. In no case, at least as portrayed in the film, did the defenders of the Catholic taboo threaten anyone with loss of career, prestige, funding, much less life or limb, as martyrs of Holocaust revisionism have not only been threatened with, but in fact, time after time, have actually sustained. The pages of this journal report case after case of these. Likewise, no protagonist in the portrayal here reviewed even sustained accusations of “anti-Catholic” or “anti-clerical” motivations, in contrast to the “anti-Semitic” and even “Neo-Nazi” accusations faced now as in the past by inquirers into the facts of the Holocaust. No violence is anywhere to be seen in the film here reviewed, something of a phenomenon itself in today’s cinema.

The saga was marked at a number of points by contact with the regnant legal system, that of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Contacts of this nature for Holocaust revisionists are almost without exception adverse, even when the defendant is not forced to admit the violation of some law, such as those against “Holocaust denial” now on the books of most of the countries of Europe. The heroes of Spotlight, on the other hand, had the law solidly on their side, and despite recalcitrance exhibited by the occasional clerk or other functionary in the court system, their motions (in cases in which they were not defendants, nor plaintiffs) were upheld and the decisions in their favor greatly aided their project.

It is no doubt critical to the course of events that the person in real life whose assumption of the editorship of the Globe, Martin Baron, was Jewish. The movie makes no bones about the fact of the character’s Jewishness, as perhaps it could not in view of all the characters’ bearing the name of the real person each portrays. Even the casting is frank: Baron is played well by Liev Schreiber, a Jew in real life who has often portrayed overtly Jewish characters in other films. But Baron’s Jewishness in this situation never appears as any sort of enmity for the Catholic Church or Christianity; it always appears convincingly that Schreiber is at worst out to kill an ancient and pernicious taboo, which will elicit cheers from every revisionist. The real person, in any case, appears to be Jewish in the secular, heredity sense and has never engaged in unseemly advocacy in favor of his religion or its client state, and his portrayal in the film adheres to this description.

Although the film offers no hint of it, the sins covered up by the broken taboo are almost certainly ancient, and they are in no way confined to the Catholic or Christian religions nor even, ultimately, to religion itself. Sexual (not to say, reproductive) prerogatives have ever inhered in those whose position in the social power structure has enabled them to exploit them. Not only have kings, princes and priests forever enjoyed peccadillos, other males (primarily) have seized upon power opportunities all the way down to footsoldiers of victorious invading armies. Feudal lords availed themselves of the rights of seigniorage, while Mohammed Himself took a three-year-old to bride, so it is told. The traditions of the defeated taboo of Spotlight are far more ancient, and widespread, than the movie could possibly have hinted, even if it had tried. What changed was the social power structure, and the role of current, accurate information in the present age.

Who is to say that the pagan priests who offered up the burnt bodies of “virgins” to the gods did not pre-empt those very gods in consuming those purported virginities, as their anointed proxies, of course, in advance of the burnt offerings? The gods might or might not be gods, or even real, but the priests were unquestionably human.

Likewise, the Holocaust is no recent invention, nor is victimology, Jewish or otherwise. It has been abundantly demonstrated in these pages how both the mantra of the Holocaust and the magic number of Six Million preceded the conflict between Germany’s National Socialists and Jewry by decades. The entire basis of Christianity is in fact a (single) martyrdom, since claimed by latter-day millions, and martyrdom maintains an especially prominent position in today’s Islam where it is most embattled.

The incident of the defeat of a millennia-old taboo against priestly opportunism is stark, but it is also ephemeral. It constitutes a step on the part of the believing multitudes from mysticism toward an awareness of facts, not only in their qualities and contexts, but in their pervasiveness among their own vast numbers.

Such an awareness is being awakened among the masses as to those others who incessantly seek after their minds and hearts, be those governments, religions, insurgents, thieves or a whole host of other seductors. If and as such awareness grows, and becomes more-discerning as to the deceptions undertaken and the rewards sought thereby, the taboos of the Holocaust face but a straitened future.

They will die, possibly even in our own lifetimes, but we will be challenged to detect just when that was.

There may be no movie. Or if there is, it may win no Academy Award.

Opponents of taboos regarding present conditions or historical legends alike will find Spotlight a gratifying experience; the good guys not only win, but they live to reap laurels for their victory. The casting and acting are well above average and the script, which hews reasonably closely to actual events, seems quite credible.

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 8(2) 2016

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a