Filip Müller’s False Testimony, Part 3

The following article was taken, with generous permission from Castle Hill Publishers, from Carlo Mattogno’s recently published study Sonderkommando Auschwitz I: Nine Eyewitness Testimonies Analyzed (Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield, 2021; see the book announcements in Issue No. 2 of this volume of Inconvenient History). In this book, it features as Sections 6 and 7 of Part 1. The other sections of Part 1 are included in the two previous issues of Inconvenient History. References to monographs in the text and in footnotes point to entries in the bibliography, which is not included in this excerpt. It can be consulted in the eBook edition of this book that is freely accessible at www.HolocaustHandbooks.com. Print and eBook versions of this book are available from Armreg at armreg.co.uk/.

6. The Cremation Furnaces at Birkenau

6.1. Müller’s Task

As seen earlier, Müller was a stoker (Heizer, furnace operator) at the Main Camp’s crematorium, but he claims to have clumsily set them on fire, which is a nonsensical tale. He then informs us (Müller 1979b, p. 50):

“During the first few months of 1943 it served simultaneously as a training centre for a new team of stokers. They were to be employed in the crematoria of Birkenau which were then being built. About twenty Jewish and three Polish prisoners were instructed in the duties of a crematorium worker by Kapo Mietek.”

However, during the Lanzmann interview, he said the opposite (2010, p. 108):

“La: You, for example, you were a fireman?

Mü: Fireman.

La: How long was the training for such work?

Mü: Yes, well, there was, there was no training. To do this activity or any activity in the crematorium, especially in the extermination sites, you needed neither a specialization nor anything close to it.”

The story of the training course at the Main Camp’s crematorium has already been told by Tauber, who claims to have stayed there from the beginning of February to March 4, 1943:[1]

“Our group, which totaled 22 Jews from Block XI and 4 Poles assigned to our group, was called ‘Kommando Krematorium II.’ We did not understand this denomination at the time, but then we were persuaded that we had been sent to Crematorium I for a month’s practice to prepare for work in Crematorium II.”

Hence, Müller and Tauber found themselves together for a month at the Main Camp’s crematorium, but they ignored each other in their respective statements.

It is not clear why a similar training course was not also undertaken for the 8-muffle furnace of Crematoriums IV and V, which had a rather different structure, operation and management than that of the double- and triple-muffle furnace of Crematorium I and II/III, respectively.

However, if we take Müller’s word for it, it can be assumed that Müller at least observed the furnaces of Crematorium II and became a stoker in Crematorium V (according to his deposition during the 97th hearing of the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial and his interview with Lanzmann, 2010, p. 50). He had thus become an expert in cremation furnaces and cremation at Birkenau. All that remains is to examine his pertinent statements.

6.2. Crematorium II

When he testified during the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial, Müller said practically nothing about the Birkenau cremation furnaces, and it is not even known what he knew about them back then. Nyiszli reported that Crematorium II/III had 15 separate furnaces, each in a single structure (Mattogno 2020a, pp. 38, 195f.). In his book, Müller wrote that there were “Five ovens, each with three combustion chambers” in Crematorium II, but a few lines later, Nyiszli’s suggestive powers took over Müller’s imagination once more (Müller 1979b, p. 59):

“Its fifteen huge ovens, working non-stop, could cremate more than 3,000 corpses daily.”

The question of the furnaces’ cremation capacity caused Müller quite some chagrin. Nyiszli, in his boundless megalomania, had written the following about that (Mattogno 2020a, p. 43; emphases added):

“The bodies of the dead are reduced to ashes in 20 minutes. The crematorium works with 15 furnaces. This means the cremation of 5,000 people a day. Four crematoria are in operation at the same capacity. Altogether 20,000 people pass each day through the gas chambers and from there into the cremation furnaces. The souls of twenty-thousand innocent people fly off through the gigantic chimneys.”

Incredibly, he believed that the four Birkenau crematoria each possessed 15 individual furnaces, in total 60! In the German translation “Auschwitz. Tagebuch eines Lagerarztes”, the translator or editor did not dare to repeat all this nonsense, and the above passage was modified (meaning falsified) as follows (Nyiszli 1961, No. 4, p. 29; emphases added):

“There are fifteen furnaces in a crematorium. This means that several thousand people can be burned every day. The crematoria often operated in day-and-night shifts. A total of 10,000 people can be transported from the gas chambers to the cremation furnaces every day.”

From Nyiszli ‘s thermotechnically absurd data – the cremation of three corpses at once in one muffle within 20 minutes, plagiarized by Müller in reference to the Main Camp crematorium[2] – results a theoretical capacity of Crematorium II/III of 3,240 corpses within 24 hours. The capacity of 3,000 corpses Müller claimed was perhaps derived from a grossly approximate calculation, but we also have to consider the related statements by Jankowski, another primary source for Müller’s plagiarism:[3]

“Crematoria II and III had 15 furnaces [muffles] each with a daily capacity of 5,000, and Crematoria IV and V had 8 furnaces [muffles] each, which cremated a total of about 3,000 corpses every day. Altogether in these four furnaces [i.e. crematoria] about 8,000 corpses could be cremated a day.”

Having opted for the cremation capacity given in the aforementioned false translation of Nyiszli ‘s claims – 10,000 corpses per day – Müller was forced to increase Jankowski ‘s data proportionally:

- Crematorium II/III: from 2,500 to 3,000; together from 5,000 to 6,000

- Crematorium IV/V: from 1,500 to 2,000; together from 3,000 to 4,000.

However, in 1946 he had asserted that Crematorium IV (=V) could burn “only about 1500 people every twenty-four hours” (Kraus-Kulka Statement).

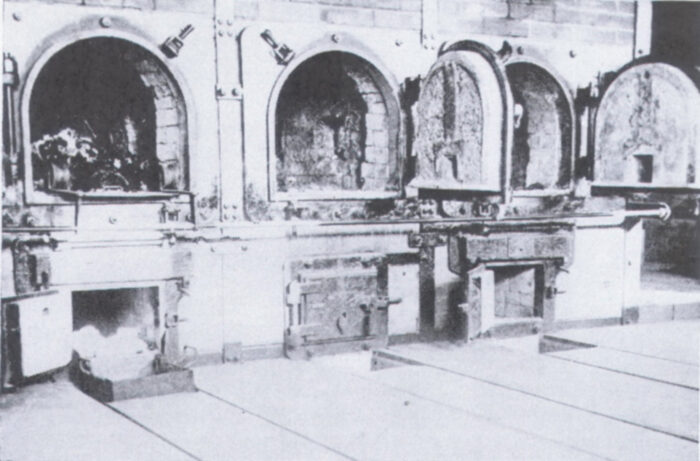

What did the stoker Müller know about the cremation furnaces? Virtually nothing. About the triple-muffle furnaces, he wrote (Müller 1979b, p. 59):

“Outwardly the fifteen arched openings did not significantly differ from those at the Auschwitz crematorium. The one important innovation consisted of two rollers, each with a diameter of 15 centimetres,[4] fixed to the edge of each oven. This made it easier for the metal platform to be pushed inside the oven.”

This is the pair of guide wheels (Laufrollen) located in front of the muffles, which ran on a folding frame that was welded to the anchor bars of the furnaces with a holding iron bar (Befestigungs-Eisen). It is clearly visible in the photograph of the Buchenwald crematorium published by Kraus-Kulka (see Document 15). As noted earlier, this device was nothing new at all, as it was also installed on the double-muffle furnaces of the Main Camp’s crematorium. Without these wheels, it would have been impossible to introduce the corpse-introduction device into the muffle without seriously damaging the refractory-clay grate.

The most-striking difference between the two furnace models, in addition to the obvious fact that the triple-muffle furnace model had one more muffle, was the gas generator: as explained earlier, the double-muffle furnaces had two gas generators in a single-wall structure as wide as the furnace itself, whereas the triple-muffle furnaces were equipped with two single gas generators installed behind the two lateral muffles, while the furnace masonry behind the central muffle was flat.[5]

In a generic context (without reference to any gassing) Müller writes (1979b, p. 82):

“Every oven had been fired since morning. We were ordered to keep the fires going which meant feeding them with two wheelbarrowfuls of coke every half hour.”

The triple-muffle furnace had two gas generators, each with a grate capacity of 35 kg of coke per hour,[6] as I will explain below.

The context makes it clear that Müller meant two wheelbarrows for each gas generator, since two wheelbarrows in ten gas generators making little sense. A wheelbarrow of coke corresponded to about 60 kg,[7] so that each gas generator would have been overloaded with 240 kg of coke per hour, hence almost seven times more coke than it could consume in an hour.

Müller says nothing about the structure and functioning of the triple-muffle furnaces, and it is clear that he had no knowledge about them. He evidently was unaware of the most-elementary facts, such as this type of furnace having precisely two gas generators placed behind the two lateral muffles, three interconnected muffles, a single blower that simultaneously fed cold air into all three muffles, and a single smoke damper. This self-proclaimed stoker did not even know the proper technical terms relating to cremation furnaces, that is, the names of the tools he claims to have worked with for many months on end.

In his book, Müller dropped the absurd story of the flame-spewing chimneys, which was so dear to many witnesses not just of the immediate post-war era. Instead, they merely emitted smoke and fumes (Müller 1979b. pp. 65, 107), although there is one reference to flames reaching the open air through the chimneys (ibid., p. 95):

“The raging flames rushed into the open air through two underground conduits which connected the ovens with the massive chimneys.”

To Lanzmann ‘s question whether the chimney of Crematorium II smoked, Müller replied:

“No, not always. Even when the chimney, that is, when the crematorium was in use, the smoke was not always so strong, that people would guess what was going on.” (Lanzmann 2010, p. 39)

Shortly after, however, he contradicted himself in a blatant way, asserting that the inmates of the Family Camp “often saw the flames from the chimney of the crematoria” (ibid., p. 62).

6.3. Crematorium V

Müller claims to have worked in this facility for a long time as a stoker, so he had to know perfectly the furnaces installed there. He said the following during the interview with Lanzmann (2010, p. 50):

“La: Yes, you were a fireman.

Mü: Yes, in Crematorium 5.

La: Yes, and what exactly was your job?

Mü: Well, the job of this fireman consisted of… he had to (remove) the corpses… that is to keep the ovens clean, to remove the ashes of the corpses…

La: With what?

Mü: With a… it was a big scraper. It was always like this, that the ovens were… there were three corpses per oven.

La: Three corpses?

Mü: Yes.

La: Together.

Mü: Together. And now let’s say if there were eight ovens in Crematorium 5, you can easily imagine, there are three new… every 20 minutes, that is, you have…

La: The burning time was 20 minutes…

Mü: The incineration time was about 20 minutes.

La: That’s quite long, isn’t it?

Mü: Yes, and so that, if you add it up, with eight ovens, there were 24 in 20 minutes, so that in one hour, you could incinerate 72 people.”

As noted earlier, these claims are thermotechnically absurd. Furthermore, these data show a maximum capacity of (72 corpses × 24 hr/day =) 1,728 corpses within 24 hours, but Müller attributed to Crematoria IV and V a capacity of 2,000 corpses in 24 hours, which, as I will explain later, had no relationship with his fantasies about a cremation technique he called “express work”.

He describes the 8-muffle cremation furnace and its operation as follows (Müller 1979b, pp. 95f.):

“In the middle [of the furnace room] stood two big rectangular oven complexes, each of which had four burning chambers. Between the ovens were the generators which lit the fire and kept it going. The coke fuel was brought in in wheelbarrows. The raging flames rushed into the open air through two underground conduits which connected the ovens with the massive chimneys. The force and heat of the flames were so great that the whole room rumbled and trembled. A couple of sweaty, soot-blackened prisoners armed with metal scrapers fitted with wooden handles were busy raking out a whitish glowing substance from the bottom of one of the ovens. It had gathered in grooves which were let into the concrete floor under the flux-holes of the oven. When it had cooled somewhat it was grey-white. It was the ashes of human beings who had been alive yesterday and had left the world after an agonizing martyrdom, without anyone taking any notice.

While the ash was being raked out of one lot of ovens, the ventilators of the one next to it were being switched on and the preparations made for a new batch. Indeed a largish number of corpses were lying on the wet concrete floor. […]

In front of each oven lay a metal trough, in the front of and under which a squared timber had been pushed diagonally, and behind there were two poles like those of a stretcher. As always, a bucket of water was poured over the trough first, then two prisoners laid three corpses on it while, with a loud rattling, the oven door was cranked up like a metal curtain. One in front and one behind, pairs of prisoners lifted up the stretcher and put it on the rollers in front of the entrance [muffle door], and pushed it into the oven. When it was pulled out an iron fork was pushed against the corpses so that they stayed inside the oven. When the oven door had been cranked down again the cremation began.”

The description is mostly correct, but some elements are described in a somewhat confused way, while others invented.

The structure of the loading stretcher is almost incomprehensible. As I have explained elsewhere,[8] this device called Trage or Tragbahre (stretcher), Einführtrage (introduction stretcher) or Leichentrage (corpse stretcher) consisted of two parallel side rails consisting of steel tubes 3 cm in diameter and about 350 cm long, on whose front half, the one that was introduced into the muffle, a slightly concave steel sheet 190 cm long and 38 cm wide was welded. Onto this metal sheet, the corpse was placed. The rear parts of the two side rails, which made up the handles, were further apart from each other for better handling (49 cm). At the front half, the distance between the two side rails was the same as the guide rollers (Führungsrollen), so that they could rest and roll exactly on them.

Müller calls the concave steel sheet a “Trog” (“trough”); as for the pieces of “squared timber” (“Vierkantholz”) placed underneath it, he does not explain that it was used to lift the stretcher at the front in order to place it onto the rollers.

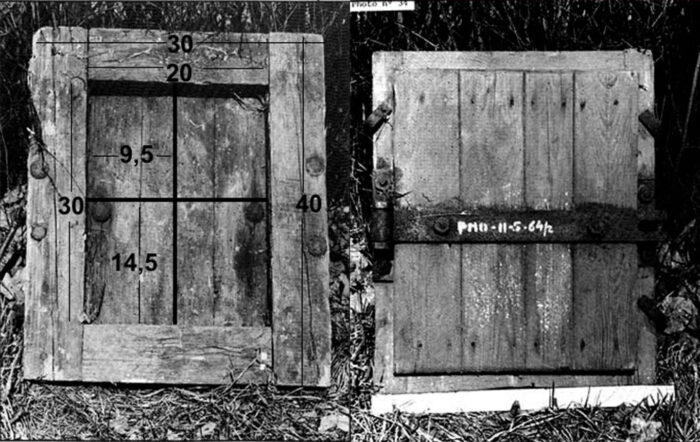

The technique of introducing the stretcher into the muffle is more or less correct, but loading the muffle with three corpses at once is absurd, as I have visually demonstrated elsewhere.28 On the other hand, the 1945 Polish photographs of the ruins of Crematorium V, which were also accessible to Müller, clearly show the introduction stretcher, a loading roller and the stokers’ tools, including a U-shaped and a V-shaped iron tool (Müller’s “iron fork”) and an ash scraper.[9] Another, close-up photo shows the stretcher resting on rollers welded to an anchoring bar of the furnace. Below it one can see the openings of the ash chambers of two muffles, with the lids of the combustion-air ducts to the right of each ash-door opening.[10] In front of the opening of the right ash-door one can see the collection pit for ashes extracted from the ash chamber, similar to the pits of the triple-muffle furnace.[11] In the foreground are lying several pieces of squared timber, presumably those used to lift the stretcher and place it on the roller.

The bottom of the ash chamber was not made of concrete, but of refractory bricks, and it also had no grooves, which would have made it difficult to extract the ash accumulated inside with the scraper, which looked like a small hoe, but with a much-wider and ‑lower blade.

The doors of the 8-muffle furnace were called Muffelabsperrschieber (muffle closing dampers). They weighed 46 kg each, and ran vertically inside a wall structure located above each pair of muffles at the front of the furnaces (Pressac called them “guillotines”). They were operated by means of pulleys fixed to the ceiling beams, wire ropes and counterweights (Mattogno 2019, pp. 237f.).

Müller mentions the ventilators of the 8-muffle furnaces also elsewhere (also as “fans,” Müller 1979b, pp. 94, 95, 98f.) and explains their purpose as follows (ibid., p. 136):

“While in the crematorium ovens, once the corpses were thoroughly alight, it was possible to maintain a lasting red heat with the help of fans, in the pits the fire would burn only as long as the air could circulate freely in between the bodies.”

However, unlike the 3-muffle furnaces, the 8-muffle furnaces were not at all equipped with blowers (Druckluftanlagen), since they were of a very-much-simplified design,[12] so that the “ventilators” or “fans” mentioned by Müller are pure fantasy, like their alleged purpose – to keep the muffles red-hot. They merely fed cold(!) combustion air into the muffle, as explained earlier. This portentous lie alone proves that Müller never worked as a stoker of an 8-muffle furnace of the Auschwitz type.

He also describes the instructions allegedly given by Oberscharführer Peter Voss for increasing the cremation capacity of the furnaces in the context of the alleged gassings of the Family Camp (ibid., p. 98):

“‘To get the stiffs burnt by tomorrow morning is no problem. All you have to do is to see that every other load consists of two men and one woman from the transport, together with a Mussulman and a child.[13] For every other load use only good material from the transport, two men, one woman and a child. After every two loadings empty out the ashes to prevent the channels from getting blocked.’ Then he continued menacingly: ‘I hold you responsible for seeing to it that every twelve minutes the loads are stoked, and don’t forget to switch on the fans. Today it’s working flat out, understood?’”

In 1944, Voss was allegedly Kommandoführer of the Crematorium IV “Sonderkommando” (Lasik, p. 302), therefore he should have known the crematoria well, but the naive instructions given above betray a total ignorance of these facilities. As I have explained extensively elsewhere, the triple- and 8-muffle furnaces were designed for the cremation of only one corpse at a time in each muffle, and their geometry reflected this. Therefore, the simultaneous cremation of several corpses in one muffle would not have increased the capacity of the furnaces, which results both from previous experience and from thermotechnical facts.[14]

Another gross nonsense is the provision to extract from the furnaces the ashes – evidently those of the cremated corpses – after every other load, that is after having cremated (5 + 4 =) nine corpses, two of which are said to have been children, in order to prevent “the channels” from getting blocked. What “channels”? The only “channels” emanating from the triple- and 8-muffle furnaces were the smoke ducts connecting the furnaces with the chimney. In the triple-muffle furnaces, the smoke duct started from two lateral openings in the center muffle’s ash chamber, where theoretically huge amounts of ashes could have obstructed it (see Document 5a in Part 2), but in the 8-muffle furnace, which is what Müller is talking about here, the ducts started from openings in the outside walls of the four outside muffles, where no ash could ever block them.[15] The ashes instead fell through the openings between the bars of the refractory-clay grate into the underlying ash chamber, from which they were extracted with a scraper through a special ash-extraction door. So how could the ashes end up in the “channels”?

On the final directive (the operations to be performed every 12 minutes) I will dwell below.

Müller then developed this thermotechnical delusion extensively. The nonsense he utters is so great that it is necessary to quote the text in full, despite its length (Müller 1979b, pp. 98-100):

“Under the direction of the Kapos, the bearers began sorting the dead into four stacks. The largest consisted mainly of strong men, the next in size of women, then came children, and lastly a stack of dead Mussulmans, emaciated and nothing but skin and bones. This technique was called ‘express work’, a designation thought up by the Kommandoführers and originating from experiments carried out in crematorium 5 in the autumn of 1943. The purpose of these experiments was to find a way of saving coke. On a few occasions groups of SS men and civilians visited the crematorium to watch the experiments. From conversations between Voss and Gorges we gathered that the civilians were technicians employed by the firm of Topf and Sons of Erfurt who had manufactured and installed the cremation ovens.

In the course of these experiments corpses were selected according to different criteria and then cremated. Thus the corpses of two Mussulmans were cremated together with those of two children or the bodies of two well-nourished men together with that of an emaciated woman, each load consisting of three, or sometimes, four bodies. Members of these groups were especially interested in the amount of coke required to burn corpses of any particular category, and in the time it took to cremate them. During these macabre experiments different kinds of coke were used and the results carefully recorded.

Afterwards, all corpses were divided into the above-mentioned four categories, the criterion being the amount of coke required to reduce them to ashes. Thus it was decreed that the most economical and fuel-saving procedure would be to burn the bodies of a well-nourished man and an emaciated woman, or vice versa, together with that of a child, because, as the experiments had established, in this combination, once they had caught fire, the dead would continue to burn without any further coke being required.

As the number of people being gassed grew apace, the four crematoria in Birkenau, even though they were working round the clock with two shifts, could no longer cope with their workload. According to the makers’ instructions the ovens required cooling down at regular intervals, repairs needed to be done and the channels leading to the chimneys to be cleaned out. These unavoidable interruptions resulted in the ‘quota’ of no more than three corpses to each oven load being kept to only very rarely.

The decision as to whether it was to be ‘express’ or ‘normal’ work was taken by the Kommandoführers. If outsiders or perhaps even the Lagerkommandant arrived at the crematorium for an inspection we switched over to normal work immediately. […]

Once the visitors had gone ‘express work’ continued at the usual pace, significantly raising the output of the ovens.”

To begin with, the expressions “express work” and “normal work” were invented by Müller and are not confirmed by any documents.

The alleged cremation experiments in Crematorium V in the autumn of 1943 are another fable, as are the arrival of SS commissions and civilians. As for the “technicians employed by the firm of Topf and Sons of Erfurt,” it is known that the creator of the triple- and 8-muffle furnaces was the engineer Kurt Prüfer, who was also responsible for their installation in Birkenau. In this capacity, he went to Auschwitz several times. His last visit in 1943 took place in late summer of 1943, in September (see Mattogno 2014, pp. 30-34). To properly assess Müller’s various claims, a brief excursus is necessary.

As soon as Crematorium II came into operation in the last third of March 1943, the three forced-draft blowers of the chimney overheated and were irreparably damaged. Eng. Prüfer and his colleague Karl Schultz, who had designed the combustion-air blower for the triple-muffle furnace, were summoned to Auschwitz on March 24 and 25 in order to discuss what to do. It was decided to remove the forced-draft systems. This work was carried out by the Topf fitter Heinrich Messing between May 17 and 19. But the Central Construction Office had already noticed earlier that the damage was even more serious: it involved the refractory lining of the chimney and the smoke ducts, which had collapsed or was damaged and had to be rebuilt. The entire affair, which I have extensively exposed in another study, dragged on for months and produced many documents. I summarize the essential points.[16]

The damage to the chimney and the flue ducts occurred in the latter half of March but was discovered only in the following month, as the Central Construction Office requested Prüfer to send a new project for the chimney lining at that time. Work on the demolition of the damaged refractory lining began a few days after the arrival of Robert Koehler’s letter of May 21, probably on May 24, after Bischoff ‘s telephone conversation with Prüfer; it stopped on 1st June, but it was not possible to carry out further repairs, because the new design of the chimney lining had not yet been received. This design project was assigned to Koehler Co. whose personnel were surely present at Auschwitz on May 29, and it is probable that Koehler took part in the demolition job. In the Topf letter of July 23 it is said that Crematorium II had been out of service for six weeks, hence since June 11, but any cremation activity surely ended earlier than that, because one cannot imagine any incinerations being carried out with workers present inside the chimney; therefore, cremations must have stopped around May 24. The crematorium was possibly used normally until the damage was discovered, but, keeping in mind the Central Construction Office’s experience with the Main Camp’s crematorium, it is difficult to believe that operation would have been at full load later on. In fact, between April 24 and 30, 1943 all windows of the furnace hall of Crematorium II as well as those of the adjoining rooms were being painted. Repair work on the chimney lining began after June 19 – when Koehler had not yet received Prüfer ‘s new design – and was essentially concluded on July 17, 1943, but it was still necessary to repair the flue ducts. Work probably ended only in late August, because on August 30 the Central Construction Office asked the Supplies Administration (Materialverwaltung) for the supply to Crematorium II of various paint products for use by the inmate paint shop.

On September 10, 1943, Prüfer went to Auschwitz to discuss the question of liability for the damage to the chimney and smoke ducts and their payment.

The story of the Topf experimental commission is also refuted by the invoices that this company sent to Auschwitz, which attest to all the work performed by it at the camp.[17]

It can therefore be asserted with certainty that cremation experiments were never carried out in the Birkenau crematoria in order to establish the coke consumption and the durations of cremations.

Müller, as I remind the reader, testified during the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial that he had been transferred to Crematorium II in the early summer of 1943 and remained there until the end of the summer, after which he was sent to Crematorium V. In contradiction to this, he wrote in his book (Müller 1979b, p. 65):

“A few days later our team was ordered to work in crematorium 3 which from the outside looked exactly like crematorium 2.”

This is clearly a mere artifice enabling Müller to claim that he was an “eye”-witness also regarding events unfolding in Crematorium III.

The fact is that, when Müller claims to have arrived at Crematorium II in late June/early July 1943, this facility was completely out of operation, as the extensive repair work on chimney and smoke ducts was still in progress, but he knew nothing of this when concocting his story.

Resuming the examination of his account, the purpose of the experiments allegedly was to ascertain the coke consumption and the durations of cremation with various types of corpses. It must be remembered that at the claimed time Müller claims to have been a stoker in Crematorium V, which means that he personally must have been involved in carrying out these claimed experiments. That this is a mere literary fiction is confirmed by the fact that he says absolutely nothing about the results of these purported experiments: how much coke did a cremation during the “normal work” regimen require? How much during the “express work” regimen? How much “to burn corpses of any particular category”?

Regarding the durations of cremations, he only generically mentions the absurd duration of 20 minutes, which should be that obtained during the “normal work” regimen. About the “express work” regimen, he limits himself to saying that it was “significantly raising the output of the ovens,” but he gives no numbers.

It is not even clear whether the cremation capacity he attributes to Crematoria II/III (3,000 corpses per day) and Crematoria IV/V (2,000 corpses per day), and therefore whether his claimed total of 10,000 per day was reached under “normal” or “express” conditions. In fact, in this regard, he becomes entangled in an inextricable contradiction. From his data for the first pair of crematoria (three corpses in a muffle within 20 minutes) results a cremation capacity of 3,240 corpses within 24 hours against the 3,000 he declared, and for the second pair of crematoria results a capacity of 1,728 corpses in 24 hours, against his number of 2,000. Hence, for Crematoria II/III, the calculated capacity is larger than his claimed average, making it look like this was the result of an “express work” regimen, whereas for Crematoria IV/V it is smaller, making it look like the result of a “normal work” regimen. Be that as it may, the difference between these two regimens is not very significant. Apparently, Müller based it more on combustibility than on the number of corpses per batch, because he considers the cremation of four corpses together in one muffle to be exceptional.

For Müller the experiments were limited exclusively to the type of corpses to be cremated. He knew nothing of the main methods to influence the speed and efficiency of a cremation – and this is no small thing for a stoker. In fact, he never mentions the elementary activities of the stoker, for example, the adjustment of the chimney damper to increase or decrease the draft, the regulation of the fire in the gas generator by appropriately adjusting its air supply, the regulation of the air flow in the muffles by means of the air-channel closures.

Experiments officially requested from the Topf company by the camp administration would have made sense only if the furnaces had been equipped with the necessary technical devices necessary to monitor and interpret numerous parameters, that is, at least of:

- an electric pyrometer to measure and record the muffle temperature,

- a device to measure the chimney draft;

- a device to measure the hearth draft;

- a combined CO/CO2 gas tester to both ensure economical combustion and detect smoke development;

- various thermometers to measure the temperatures in the ash chamber, the smoke duct and of the combustion air fed into the muffle.

By way of comparison, see the real cremation experiments performed in the crematorium of Dessau between 1926 and 1927 by German Eng. Richard Kessler (Mattogno/Deana, Vol. I, pp. 61-73).

In his extensive ignorance, Müller considered cremation an automatic process that required external interventions at specific times rather than depending on the course of the process, which could vary from corpse to corpse. In fact, claims that instructed to “poke” (what? The coke? The corpses? Both?) every 12 minutes and turn on the fans. Since the air blowers, where they existed (the double- and triple-muffle furnaces), were used to feed cold air to the corpse inside the muffle, poking the coke would probably help kindling the combustion inside the hearth a little – although this benefit is basically canceled out by the simultaneous entry of cold air through the open hearth door – but turning on the air blower simultaneously would definitely cool down the muffle, hence slow down the cremation!

Here, however, Müller speaks of the 8-muffle furnace, which was devoid of any “fans” (blower).

And what does every 12 minutes mean anyway? If Müller meant 12 minutes from the introduction of the corpses into the muffles, there would have been nothing to “poke,” because the evaporation of the water contained in the corpses would have only just begun. “Poking” the coke on the hearth grate, on the other hand, would have been of little use, because given a defined hearth capacity and a full load of coke in it, the amount of heat and combustion gases produced by the hearth depended on the amount of air fed through the hearth, hence on the chimney’s draft and on the proper adjustment of the hearth’s air-channel closure, not on getting poked. Such a 12-minute interval is also completely inconclusive, because 12 minutes is not a factor of 20 minutes, the claimed cremation time. Anything poked every 12 minutes would have happened at different phases of each subsequent cremation.

Müller’s assertion that, “once they had caught fire, the dead would continue to burn,” applied to all types of corpses, as long as the temperature inside the muffle did not drop below 800°C, which is necessary for the combustion of proteins (ibid., p. 31). But the continuation of his sentence – “without any further coke being required” – is simply wrong, because even after the entire refractory mass of these furnaces had reached operating temperature, they could not function without further heat input, by merely feeding on the bodies themselves. In fact, the initial endothermic, meaning heat-absorbing, phase of cremation required a very large quantity of heat, as shown by the experiences conducted with civilian furnaces.[18] Müller’s idea that, once the furnaces had reached thermal equilibrium, cremation proceeded by itself without further consumption of any fuel, is therefore a technical absurdity. Jankowski also insisted on this legend, specifically with regard to the 8-muffle furnace in Crematorium V (see Chapter 8):

“In each opening of the furnace, three corpses were introduced with stretchers that moved on rollers. When the furnaces were properly heated, the corpses burned by themselves for weeks on end.”

I have discussed this particular absurdity in depth in another study, to which I refer (Mattogno 2020c, Chapter 18, pp. 171-179).

Returning to Müller, the different combustibility of various types of corpses was a fact known since the 1930s. Since 1931, Eng. Friedrich Hellwig had found that, out of 100 corpses, 65 burned normally, 25 with difficulty, and 10 with great difficulty (Mattogno/Deana, Vol. I, p. 106).

In 1933, Eng. Hans Keller wrote (ibid., p. 91):

“There are corpses which burn easily and thus require a short time for the cremation. But there are other corpses that do not want to burn, requiring three hours and even longer. This variability shows up also in the composition of the gas and in the temperature. Corpses burning easily will initially produce up to 16%, even 17% of CO2; with corpses that are difficult to burn, this value goes down to 4%.”

Subsequent experiments conducted by the same engineer in the early 1940s showed that body fat was one of the main elements of the combustibility of corpses (ibid., pp. 71-73; Mattogno 2020c, pp. 174f.).

In Birkenau, the proportion of corpses that burned badly had to be prevalent for obvious reasons: Jews deported from Europe’s ghettos and collection camps were usually undernourished, and camp inmates who died of diseases were often very emaciated. Therefore, a cremation duration of 20 minutes – so widespread in anecdotal tales about Auschwitz – is even more of an utter absurdity.

Although cremation experiments were not carried out in the Birkenau crematoria, it is still possible to imagine that some elementary knowledge of thermotechnics and the experience acquired led the stokers to carry out a rational distribution of the corpses in the furnace muffles – not several adult corpses in a single muffle, though – for instance by combining emaciated bodies with more-or-less-normal bodies in alternating, interconnected muffles. In fact, both in the triple-muffle and in the 8-muffle furnaces, all the muffles were interconnected. In the triple-muffle furnace, the gases produced by the two gas generators entered the outer muffles, and from these, through special openings in the dividing walls, they flowed into the central muffle, from where they passed into the smoke duct and into the chimney. In the 8-muffle furnace, each of the four gas generators fed a pair of interconnected muffles. The combustion products of the gas generator entered the first, outside muffle, from which they passed into the second muffle, then exited through the smoke duct. Given this structure, even if we limit the issue exclusively to the combustibility of the corpses, it was not irrelevant to introduce a certain type of corpse into the first and a different type into the second (or third) muffle. The choice could therefore only concern the placement of an emaciated corpse and a more-or-less-normal one in alternating muffles, but Müller displayed no knowledge of this.

All this confirms that his narration is a senseless, invented tale with no basis in reality.

7. The Extermination of the Hungarian Jews and the Cremation Pits

7.1. The Repair Work of April 1944

On March 18, 1944, Hitler met the Hungarian regent Miklós Horthy at Schloss Klessheim, near Salzburg. As a result of this meeting, Horthy agreed to make available to the Third Reich 100,000 Jewish workers and their families (Braham 1963, p. 363). The figure was then doubled: on May 9, Hitler ordered 10,000 troops to be withdrawn from Sevastopol in order to guard the approximately 200,000 Jews. These Jews were to be sent to various concentration camps of the Reich, where those fit for labor among them would be employed in the “interceptor construction program” (NO-5689), a desperate German attempt to turn the tide of the war by regaining air superiority in Europe. In these agreements lie the origin and purpose of the deportation of the Hungarian Jews, which clearly had no exterminating purpose.

A letter of May 4, 1944 by Edmund Veesenmeyer, the plenipotentiary of the Reich in Hungary, already mentioned a plan to deport 310,000 Jews (NG-2262). From May 17, Hungarian Jews began to pour into Auschwitz, and deportations continued until July 11. The number of Jews deported from Hungary eventually amounted to 437,402, but no more than 398,400 of them reached Auschwitz, even though the actual number is probably closer to about 321,000. It is documented that at least 107,200 of them were declared fit for labor. Since it is known that 30-33% of the deportees belonged to this category, the total number of Hungarian Jews arriving at the Auschwitz Camp would be around the lower number just mentioned. Of these 107,200 deportees, about 28,000 were registered in Auschwitz, while the remaining 79,200 were transferred to other camps through the Birkenau transit camp (see Mattogno 2007).

In the imaginative narrative of the Auschwitz resistance groups, this deportation essentially aimed at extermination, so they invented frantic preparation activities by the SS at Auschwitz. Müller jumped on this propaganda bandwagon and told it this way (1979b, p. 124):

“In addition to several prisoner teams civilian workers from a factory in Upper Silesia were called in to overhaul the crematoria. Cracks in the brickwork of the ovens were filled with a special fire clay paste; the cast-iron doors were painted black and the door hinges oiled. New grates were fitted in the generators, while the six chimneys underwent a thorough inspection and repair, as did the electric fans. The walls of the four changing rooms and the eight gas chambers were given a fresh coat of paint.

Quite obviously all these efforts were intended to put the places of extermination into peak condition to guarantee smooth and continuous operation. What mystified us not a little, however, was the beautification of crematorium 5, where everything in sight was whitewashed.”

According to Müller, these repair works were carried out between April 7 (ibid., p. 120) and before the end of the month, when rumors spread of the imminent arrival of Hungarian Jews (ibid., p. 124).

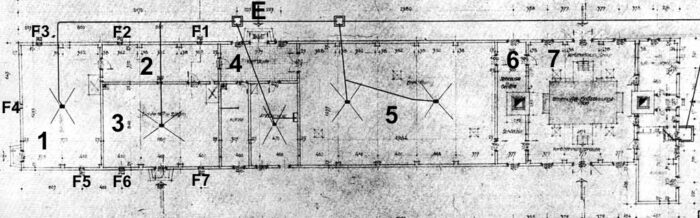

The documents show the following, however (Mattogno/Deana, Vol. I, p. 245). On April 13, 1944, the Central Construction Office ordered the locksmith workshop of the DAW (Deutsche Ausrüstungswerke; an SS-owned handicraft business) to “overhaul 20 furnace doors and 10 scrapers at Crematoria II and III.” The job was completed on October 17, 1944. In early May, damage to the brickwork was discovered, certainly in the smoke ducts or the chimneys, because on May 9, the head of construction of Concentration Camp II (Birkenau) asked the camp headquarters for a “permit for entry to Crematoria I-IV” to be issued for the Koehler Co., because that firm had been ordered to execute “urgent repairs on [the] crematoria.” At the end of the month, more damage struck the furnaces. On May 31, the crematoria administration at Birkenau ordered DAW to repair two muffle doors and five closures, plus other minor jobs. The repair work was done between 20 June and 20 July. A later order, dated 7 June 1944, concerned “required repairs on Crematoria 1-4 between 8 June and 20 July 1944.” The job ended on September 6, 1944.

Thus, in April 1944 there was only one repair concerning furnace doors, which Müller knew nothing about, who claimed only that those doors were merely painted. All the other jobs he mentioned are completely invented: filling cracks, installing new grates (muffles or hearths?), inspecting the chimneys, overhauling the fans. The subsequent damage to chimneys and/or smoke ducts is equally unknown to Müller, starting with that which occurred in early May, even before the arrival of the Hungarian Jews.

The last phrase in the above quotation from Müller’s book – “everything in sight was whitewashed” – is an abridged, sanitized translation of the original German sentence, which reads (1979a, p. 197):

“For not only were the firebricks of the two furnace complexes painted there, but also the joints between the bricks on the walls were painted white.”

This statement is in direct conflict with his self-proclaimed status as a former stoker, therefore a cremation expert by practice, because it makes no sense that “firebricks” (“Schamottziegel”) of the 8-muffle furnace were painted, because this type of bricks was obviously inside the furnaces (in the muffles, ash chamber and gas generators), while the external layer, paintable at will, consisted of ordinary bricks. Nor does it make sense that “the joints between the bricks on the walls were painted white” as well, which presupposes the presence of exposed bricks. As is clear from the building description attached to the handover negotiation of Crematorium V of March 19, 1943, however, the interior walls of that facility were “plastered and whitewashed brick masonry”.[19]

7.2. The Gassings

Müller emphatically summarizes the tally of the alleged extermination of the Hungarian Jews (1979b, p. 143):

“Since the previous night 10,000 people had perished in the three gas chambers of crematorium 5 alone, while on the site of bunker 5 with its four gas chambers corpses were burnt in four pits. In addition, in crematoria 2, 3 and 4[20] with a total of five gas chambers and thirty-eight ovens work went on at full speed. Taking this kind of ‘plant capacity’ into consideration it will be readily understood how it was possible to exterminate about 400,000 Hungarian Jews within a few weeks.”

Müller is silent that there was a transit camp in Birkenau through which, as mentioned earlier, at least 79,200 unregistered Hungarian Jews passed, to which another 28,000 registered deportees must be added, which means that, from an orthodox point of view, at least 107,200 deportees were spared the “gas chamber.” In 1979, the 1964 edition of the “Kalendarium” of Auschwitz was still unchallenged, in which Danuta Czech ignored the Birkenau transit camp, and considered all Hungarian Jews deported to Auschwitz who had not been registered as having been gassed. Since just over 29,100 had been registered (Mattogno 2007, p. 4), the balance of gassed people was assumed to have been (437,402 – 29,100 =) about 408,300, or approximately 400,000, a figure also influenced by the statements of former Camp Commandant Rudolf Höss, who had mentioned this figure.[21]

It is clear that any true “eyewitness” of the “Sonderkommando” could not have omitted such an important fact in good faith.

The expression used by Müller – “Since the previous night” – indicates that he was talking about an entire day of 24 hours of activity; therefore, about 10,000 people had been gassed in Crematorium V within 24 hours.

There is a parallel passage in his book, German edition, that provides further details (1979a, p. 215):

“Since the previous evening, three transports had disappeared in the gas chambers of Crematorium V at an interval of about four hours and were gassed. After the screaming, moaning and groaning had ceased, the gas chambers were vented for a few minutes. Then the SS men drove in inmate units to remove the bodies.”

The sanitized English edition cuts that paragraph short to just one sentence (1979b, p. 135):

“Since last night three transports had disappeared into the gas chambers of crematorium 5.”

“A few minutes” of ventilation is ridiculous, because Crematoria IV and V did not have any mechanical ventilation systems, and the structure of the facility made any passive ventilation very difficult. Under such circumstances, even the ventilation time prescribed by the contemporary German “Guidelines for the Use of Prussic Acid (Zyklon) for Destruction of Vermin (Disinfestation)” – 20 hours[22] – would have been insufficient to remove all toxic fumes, so a ventilation time of just a few minutes is utter nonsense. (The question is explored further in Chapter 9.)

In such conditions, driving “Sonderkommando” inmates into the gas chambers would have been catastrophic, especially since they allegedly did not wear any gas masks. I noted earlier that Müller describes the smell and taste of hydrogen cyanide, which assumes he was not wearing a gas mask. In this regard he explained to Lanzmann (2010, p. 111):

“La: They had no gas masks?

Mü: Yes, at times there were gas… the gas masks, but the filters, which were used, weren’t appropriate for this situation, so that breathing in the, in the gas masks was impossible.

La: Impossible?

Mü: Yes, very minimal. Yes, restricted to just a very short time.”

The gassing of a transport within four hours is a fiction even from the orthodox perspective. Müller explains: “During the day-shift there were, on average, 140 prisoners working in and round crematoria 4 and 5,” which were broken down as follows:

- 25 corpse “bearers” cleared the gas chambers and carried the bodies to the pits;

- 10 “dental mechanics and barbers” extracted gold teeth from corpses and cut women’s hair;

- 25 corpse “bearers” arranged the corpses in the cremation pits in three layers;

- 15 “stokers” carried out the cremation;

- 35 inmates made up the “ash team” responsible for removing the ashes from the pits and transporting them to the “ash depot” and pulverizing the bone residues.

The remaining 30 inmates were divided into two teams: “a smaller group” took care of the victims’ clothes, the others “ worked in crematorium 4, where operations went on ‘normally’” (Müller 1979b, pp. 136f.).

In practice, if these three batches of gassed deportees contained the 10,000 deportees mentioned in the quotation at the beginning of this subchapter, then within four hours over 3,300 deportees had to enter the gas chambers, be gassed and subsequently their bodies taken away by 25 inmates outside the crematorium, to the cremation pits at a distance of at least 10-20 meters, as I will clarify in the following subchapter. Each one would have to drag 133 corpses, and this operation alone, even if it had taken only two minutes back and forth, would have lasted more than four hours. The claimed workforce was simply inadequate.

In the passage I quoted above, Müller states that in Crematorium V “three transports” were gassed, but he also says that “each transport had up to 5,000, 5,000 people on it.” (Lanzmann 2010, p. 47). If that was so, three transports would have amounted to 15,000 people, not 10,000. According to his indirectly claimed percentage of deportees alleged gassed (400,000 out of about 437,000 deportees in total), which is 91.5%, the actual number of victims to be processed from these three transports would have been about 13,700.

7.3. Cremation Pits and Air Photos of Birkenau

Müller relates that in early May 1944, as part of the preparations for the claimed gassing of the Hungarian Jews (Müller 1979b, pp. 125f.):

“Soon after his arrival Moll ordered the excavation of five pits behind crematorium 5, not far from the three gas chambers.”

On this issue too, two of Müller’s colleagues, Tauber and Dragon, had testified in a similar vein. Tauber had mentioned the cremation pits already in his interrogation by the Soviets of February 27, 1945, albeit vaguely and claiming that there were four of them rather than the canonical five:[23]

“In the summer of 1944, many people were exterminated; for the extermination, 4 crematoria and 4 large fires [больших костра] were operating, French and Hungarian members of the resistance were exterminated.”

The legend of members of the French Resistance being exterminated in Auschwitz was in vogue in 1945. The Jewish historian Filip Friedman wrote that 670,000 [sic!] “‘Terrorists,’ meaning patriots and partisans from France” were transported to Auschwitz and murdered in the summer of 1944 (Friedman, p. 74), and in 1956, Jan Sehn still spoke of “members of the French resistance movement” who were allegedly sent to Auschwitz during the months of May to August 1944 (Sehn, p. 118).

In a subsequent interrogation, Tauber did not know much more about the cremation pits, and only corrected the number and eliminated any reference to the French partisans:[24]

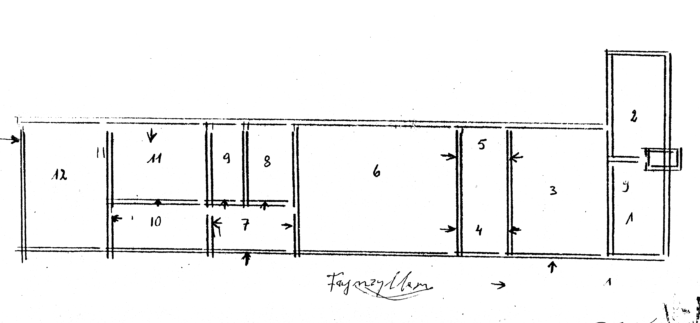

“In May 1944, the SS ordered us to dig five pits in the courtyard of Crematorium V, in the area between the drainage ditch and the crematorium building, in which the corpses of the gassed people were cremated who had come with the Hungarian mass transports.”

Dragon, on the other hand, had a more-vivid fantasy, as he also indicated the size and cremation capacity of the pits:[25]

“However, because the crematoria were not very productive, pits were dug next to Crematorium V for the cremation of the gassed Hungarians. There were 3 larger and 2 smaller graves.”

“At the beginning of May 1944, transports of Hungarian Jews began to be gassed and cremated in Crematorium V. The corpses of the gassed of some of the first transports were cremated in the furnaces of Crematorium IV, because at the time the chimneys of Crematorium V were out of order. Eventually the Hungarian Jews were burned in pits dug for this purpose near the building of Crematorium No. V. Five pits 25 meters long, 6 meters wide and 3 meters deep were dug. About 5,000 people were burned in the pits a day.”

Hence, the pits were all the same size after all. He evidently did not remember having declared shortly before that three of them were of a larger, and two of a smaller size.

Müller was liberally inspired by his colleagues. According to him, the first two pits were 40-50 meters long, 8 meters wide and 2 meters deep, hence with an average surface of (45 m × 8 m =) 360 m², and a volume of (360 m² × 2 m =) 720 m³. Towards the middle of May, Moll is said to have had another three pits dug in the courtyard of Crematorium V, and another four in the vicinity of “bunker 5” (Müller 1979b, pp. 132f.). Müller does not indicate their dimensions, but he told Lanzmann that the five pits at Crematorium V measured about 40 meters long, 8 meters wide and over 2.5 meters deep. They were located 10-20 meters away from the building, and in each one, 1,200-1,400 corpses could be burned within 24 hours. Regarding the pits at “bunker 5,” he claimed that 1,400 corpses could be cremated in each of them within 24 hours (Lanzmann 2010, pp. 51f.). This confirms that, for Müller, all of the nine claimed pits had similar, standardized dimensions, so we can start with these data (I use the depth given in his book, 2 m): total area of the five pits near Crematorium V (360 m² × 5 =) 1,800 m², total volume (1,800 m² × 2 m =) 3,600 m³; for the four pits near “bunker 5”: (360 m² × 4 =) 1,440 m², (1,440 m² × 2 =) 2,880 m³.

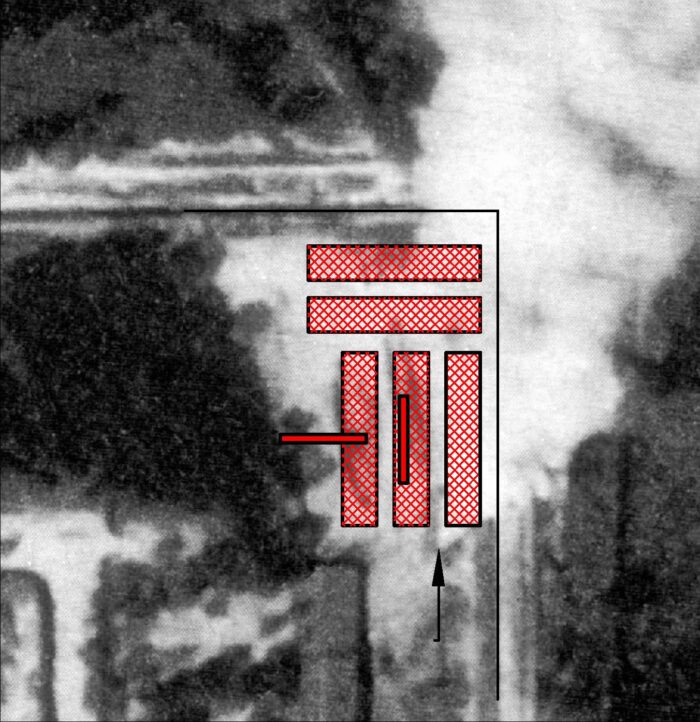

In a separate study dedicated to the claimed 1944 outdoor cremations in Birkenau (Mattogno 2016a, pp. 57-79), I documented that in the various air photos taken by U.S. and British reconnaissance aircraft during the period of the claimed peak of Jewish extermination (May 31, June 26, July 8, August 20, 23 and 25 and September 13), there is not the slightest trace of cremation pits, smoking or non-smoking, in the vicinity of the alleged “Bunker V.” In the northern Courtyard of Crematorium V, on the other hand, there is only one smoking surface, but it is very small, of about 50 m². As for the images, I refer to the respective photo documents in that study, but here it is worth reproducing a section enlargement of the photo showing the area of the Birkenau Camp, taken by an aircraft of the Royal Air Force on August 23, 1943 (see Document 17), which shows the only smoking site of the entire camp (see Document 18). To give an idea of the size, the building that can be seen partly on the left, entirely in Document 16, was Crematorium V, 12.85 meters wide and 67.50 meters long, hence with a surface area of 867.3 m². Therefore, if Müller’s claims were true, there would have been a total area of cremation pits measuring 1,800 m² in the northern courtyard of Crematorium V, which is more than twice the area covered by Crematorium V. To this, we would have to add the space between those pits required to tend the fires (move corpses, firewood and cremation remains), and the space required to store the immense amounts of firewood needed. Here I won’t go deeper into this topic.

Müller does not resist the temptation to tell another atrocious anecdote that was part of the legend spread about Auschwitz. Among Moll ‘s pastimes was this (Müller 1979b, p. 141):

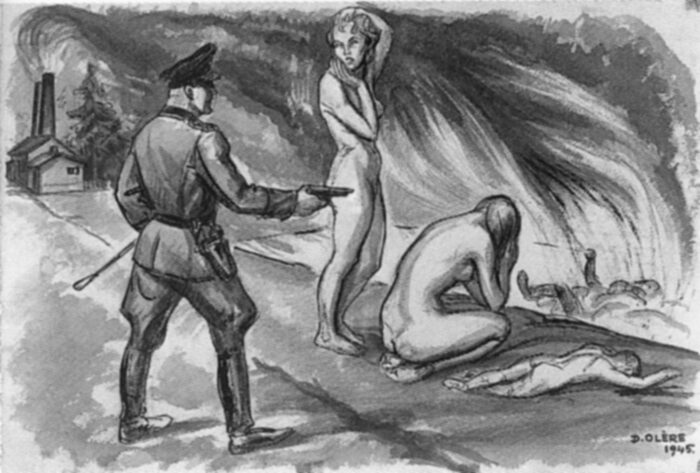

“Like a meat inspector he would stride about the changing room, selecting a couple of naked young women and hustling them to one of the pits where corpses were being burnt. Faced with the sight of this pit of hell the women were distracted. They stood at the edge of the pit, rooted to the spot, gazing fixedly at the gruesome scene at their feet. Moll who was watching them closely got a tremendous kick out of their terror. In the end he shot them from behind so that they fell forward into the burning pit.”

Why would Moll have picked out two deportees and kill them separately in a cremation pit? It would be a rather childish sadism. In fact, this story uses a theme of another camp legend: the mass shooting of deportees with a blow to the nape of the neck at the edge of the cremation pits. The most-prominent and fervent “eyewitness” and supporter of this legend was Nyiszli, who told this tale in exhaustive detail in Chapter XIII of his 1946 book (Mattogno 2020a, pp. 57-60). When this absurd story was later abandoned, it left exactly the anecdote in question as a “sadistic” residue. It was turned into “art” by another self-proclaimed “Sonderkommando” member, David Olère, in a painting from 1945 (Olère, p. 79; see Document 19), and it is clear that Müller’s story is a simple commentary on the scene painted by Olère: precisely two women on the edge of a burning pit, one of whom looks away from it; behind them, Moll, with gun in hand, is about to kill them. The scene is purely imaginary. In reality, the women on the edge of the pit would have burned alive due to the fire’s intense heat, without any intervention by Moll needed, who himself would have gotten seriously burned as well.

However, this picture is important because it locates the cremation pit in relation to Crematorium V, which can be seen in the background. The longest side of the pit is parallel to the crematorium, meaning it follows the east-west direction.

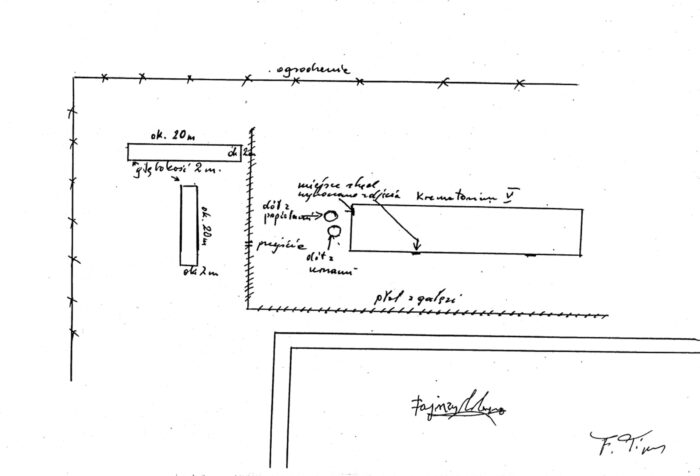

The aforementioned air photo irrefutably shows that the story of the five cremation pits is a patenthetic lie. In this context, it is important to underline that a colleague of Müller, Jankowski, gave a testimony in this regard, which is in direct conflict with Müller’s claim:[26]

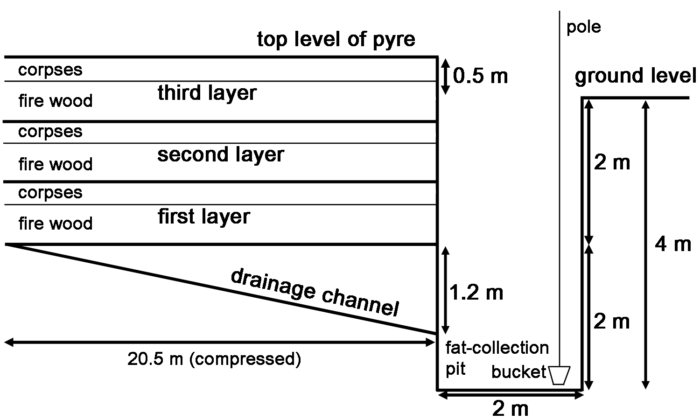

“The cremation pits, of enormous capacity, were located west of the gas chambers of Crematorium V, at a distance of a few tens of meters. There were two pits, and each could hold about 2000 corpses. The corpses were placed on layers of wood, alternatingly corpses of men and women, because they burned better that way. Corpses of children were also burned there. The cremation pits operated at the same time as the furnaces. Outflows [= drainage channels] of human fat had been dug in the pits, but I could not verify that the fat was collecting in them – the corpses simply burned completely.”

The attached drawing (see Document 20) gives the pits’ dimensions (20 m × 2 m × 2 m) and their location. In Document 21, I have scaled Müller’s five pits, with the minimum dimensions of 40 m × 8 m, in an arrangement compatible with the available space, as well as Jankowski ‘s two pits, which would have existed in the same place and at the same time. The contradiction could not be more glaring: in the northern courtyard of Crematorium V, there were five pits with minimum dimensions of 40 m × 8 m × 2.5 m (320 m², 800 m³), which a maximum capacity of 1,400 corpses within 24 hours, if we follow Müller; for Jankowski, however, there were only two pits, measuring 20 m × 2 m × 2 m (40 m², 80 m³). Although Jankowski ‘s pit had only 10% of the volume of the pits claimed by Müller, its cremation capacity was inexplicably 40% larger!

There is another drawing, by an unknown author, which also has as its subject Crematorium V (Dałek/Świebocka, Drawing 18; see Document 22). That it is precisely this facility is evident from the fact that it is surrounded by trees (Crematorium IV was located in an open space). The building, seen from the west, is drawn quite correctly: it shows the lower annex which contained the supposed gas chambers, and the structure of the crematorium proper with its two high chimneys (although the three dormers on the roof did not exist, and the doors and windows are very rough). This drawing depicts another theme of the camp’s black propaganda: a column of Jews is escorted to the crematorium, approaching the building from the west (the editors commented it with: “Do gazu,” “Into the gas”), but west of Crematorium V there was only the camp fence. There is no cremation pit in this drawing.

7.4. The Cement Platform

Within the context of the imaginary cremation pits, Müller adds another fable, which he lays out as follows (1979b, p. 133):

“In this connection Moll had thought up a new technique to expedite the removal of ashes. He ordered an area next to the pits adjoining crematorium 5 and measuring about 60 metres by 15 metres to be concreted; on this surface the ashes were crushed to a fine powder before their final disposal.”

This also refers to May 1944. Such a platform, which had to have a minimum thickness of some 10 cm for the claimed function, would have had an area of 900 m² and a volume of at least 90 m³. Even if it had been ordered by Moll himself, the Central Construction Office necessarily would have been in charge of implementing it. According to the bureaucratic practice in force at the time (see Mattogno 2015, 2016b, pp. 23-28) – leaving out Office Group C (Construction) of the SS Economic and Administrative Main Office, which issued the relevant construction orders –, at the local level every construction project of any type initially required to define an official construction site, identified by a number and a name (e.g. Crematorium II was BW 30 – Krematorium). For its realization, any and all construction sites required various documents: location sketch (Lageskizze), project description (Baubeschreibung), cost estimate (Kostenvoranschlag), floor plan (Lageplan), explanatory report (Erläuterungsbericht), handover negotiation to the camp administration (Übergabeverhandlung), notification of completion (Meldung der Fertigstellung).

The execution of the work, which was carried out by the Central Construction Office through the various labor units of its workshops, also required the completion of other paperwork: request to the supply’s administration (Anforderung an die Materialverwaltung), the project assignment (Auftrag), labor cards (Arbeitskarten), receipts (Empfangsschein) and the delivery slips (Lieferschein). The prisoners’ work was accounted for by the camp administration and billed to the Central Construction Office with an invoice (Rechnung). For almost all known projects ever built by and at the Auschwitz Camp, at least some of these documents have survived.

That said, there is not the slightest hint in connection with Müller’s concrete platform in the Central Construction Office documentation, and it does not appear in the list of construction projects either.

The air photos of Birkenau, starting with the very-clear American ones of May 31, 1944 show no trace of this platform (see Mattogno 2016a, Docs. 18 + 23, pp. 162, 167). Furthermore, no orthodox Holocaust “expert” who has analyzed these photographs (Dino A. Brugioni and Robert G. Poirier, Mark van Alstine, Carroll Lucas, Nevin Bryant; ibid., pp. 50-57) reported to have identified it.

The claim that such a platform existed is therefore unfounded and moreover refuted by air photos. In other words, it is simply a fairy tale, but in this specific case it is also another case of plagiarism. In fact, in the typewritten transcription of Höss ‘s handwritten declaration of March 14, 1946 we read:[27]

“After cleaning out the pits, the remaining ashes were crushed. This happened on a cement slab where inmates pulverized the remaining bones with wooden pounders.”

This alone suffices to put to rest definitively the tall tale of the cremation pits, but Müller seasons it with such enormous nonsense that it is an affront to intelligence. Nevertheless, his claptrap is usually accepted as sacrosanct truth by orthodox Holocaust historians, and this is precisely what makes the following discussion necessary.

7.5. Excavation and Transportation of Excavated Soil

As we have seen before, the five phantom pits in the courtyard of Crematorium V are said to have had a total volume of 3,600 m³. It is known by experience that the volume of soil increases by 10-25% when excavated (Colombo, p. 237). Therefore, the actual volume of the excavated soil was at least 3,960 m³, assuming the minimum expansion value. What happened to this soil? Müller explains it more than once (1979b, p. 127):

“The soil which we had dug out was loaded on to wheelbarrows and, under the watchful eyes of our tormentors, wheeled away at the double.”

“Even removing the soil, which had become even heavier due to the rain, became more exhausting and time-consuming.” (1979a, p. 207; omitted from the English edition, 1979b, p. 130)

“Together with a few others, I had to use wheelbarrows to remove the rest of the excavated soil that was still lying around the edge of the pits.” (1979a, p. 209; cut short in the English edition, 1979b, p. 131, to “I […] was ordered to remove earth in wheelbarrows instead.”)

The place where the soil was deposited is never indicated by Müller, but it had to be so far from the pits as not to hinder the necessary cremation operations for which they were dug.

The “Explanatory Report on the Preliminary Project of the New Construction of the Waffen-SS Prisoner-of-War Camp, Auschwitz, Upper Silesia,” states that the soil of the Birkenau area, beneath the topsoil, consisted of chalky clay with small amounts of sand and gravel.[28] The specific weight of dry clayey soil ranges from 1,700 to 2,000 kg per cubic meter (Colombo, p. 65). Under the minimum value, the 3,960 cubic meters of soil that needed to be hauled away weighed some 6,732,000 kg. Since the Birkenau Camp was located on swampy meadows, the soil by force must have been wet, hence its weight must have been considerably higher. Assuming a load of 60 kg of soil per wheelbarrow (which exceeds 90 kg with the weight of the wheelbarrow),[29] at least 112,000 trips would have been required to remove this quantity of soil. Müller does not specify how many inmates were involved in this work, but states that by the middle of May the “Sonderkommando” consisted of 450 inmates (1979b, p. 132). In fact, on May 15, 1944, the strength of the crematoria staff (“Heizer Krematorium”) was 318 inmates, guarded by 4 guards(!), of whom 157 worked in Crematoria IV and V,[30] probably 78 in one and 79 in the other.

By way of comparison, the company Ing. Richard Strauch of Krakow, in its response to a tender for drainage works in Construction Section II of Birkenau which it sent to the Central Construction Office on October 1, 1942, calculated the following times for each inmate:

- Loosen and put on the edge [of the canal] 1 cubic meter of shovable soil: 0.95 hours

- Load 1 cubic meter of soil onto a dump truck: 0.84 hours

- transport 1 cubic meter of soil by dump truck up to a distance of 50 m and tip over: 0.16 hours.

In total: 1.95 hours per cubic meter.[31]

For the 3,960 cubic meters of soil mentioned above, when hypothetically employing the aforementioned 79 detainees for 10 hours a day, these operations, which supposedly started in early May 1944, would have required (3,960 m³ × 1.95 hrs/m³ ÷ [10 hrs/day × 79 inmates]) ≈ 10 days. Here, however, a dump truck was envisaged for transporting the soil, while the case narrated by Müller, as I have already pointed out, would have required 112,000 wheelbarrow trips. This means that roughly half the work force would have done nothing else but hauling soil from the pits to wherever it was deposited. Taking this into account basically doubles the time it would have taken to excavate these pits, thus lasting toward the end of May 1944.

Since the first Hungarian Jewish deportees arrived in Auschwitz on May 17, 1944, the timing of the preparations for the alleged extermination is completely upset.

Furthermore, there is not the slightest documentary trace of these gigantic works. In particular, there is no sign in the air photos of the nearly 4,000 cubic meters of excavated soil piled up near the alleged cremation pits.

7.6. The Pit’s Structure and the “Recovery of Human Fat”

Among the resistance-propaganda nonsense that Müller retold, the tall tale about the recovery of human fat in the cremation pits is undoubtedly the grossest. Since I have dealt extensively with this topic in a specific article (Mattogno 2014a), I will repeat here only the essential points.

Müller’s related statements are quite lengthy, so I summarize how his imaginary cremation pits were structured. As mentioned earlier, their dimensions were 40-50 m × 8 m × 2 m. From the center, two channels 25-30 centimeters wide which “sloped slightly” ran transversely towards the two edges of the pit and ended in two “collecting pans,” one on each side, dug at the bottom of the pit (1979b, pp. 130-132). The arrangement of the pyre was as follows: a layer of “old railway sleepers, wooden beams, planks, and sawdust,” covered with dry fir branches, then, above it, a layer of 400 corpses, placed side-by-side in four rows; then two more similar layers, so that the pyre contained 1,200 corpses (1979b, p. 137). The last layer “protruded about half a meter out of the pit,” which evidently meant that the pyre rose half a meter above the surrounding terrain (1979a, p. 219; omitted from the English edition; 1979b, p. 137). Cremation lasted five or six hours (1979b, p. 138). The claimed five graves therefore had a cremation capacity of (1,200 × 5 =) 6,000 corpses in five to six hours.

Here Müller imaginatively reworked the fairy tales bandied about already in 1945, expressed by colleague Tauber in the following manner:[32]

“At first wood was placed in the pit, then 400 corpses alternating with branches, they were sprinkled with gasoline and set on fire. Then the remaining corpses [coming] from the gas chambers were thrown into it, from time to time the fat of the corpses was poured back. A pyre burned for about 48 hours.”

Müller does not indicate the dimensions of the two fat “collecting pans,” so we must turn to the only witness who provides them, precisely Tauber:32

“The pyres for burning the corpses were placed in pits, at the bottom of which, for the entire length of the excavation, there was a channel for the access of air. From this channel, there led a branch to a hole 2 x 2 x 4 m deep.”

With these data, half of the cremation pit was 22.5 meters long (based on the average length of 45 m), 2 meters of which were occupied by the collection pit. If we assume a slope of some 6% for the fat-collection channel,[33] it descended to a depth of (20.5 m × 0.06 =) approximately 1.2 meters from the bottom of the cremation pit, and the bottom of the fat-collection pit was 2 meters below the pit’s bottom, hence 80 cm deep from where the collection channels entered it. I illustrated the structure of a (mirror) half of this pit in Document 23.

The average body-fat content in normal men (average weight 70 kg) and women (average weight 60 kg) aged 25, 40 and 55 amounts to approximately 16.8 kg.[34] The people allegedly gassed, however, came from ghettos or collection camps where food was notoriously scarce. In the Minnesota Starvation Experiment, which was performed between November 1944 and December 1945, 36 volunteers subjected to it lost 67% of their total body fat (Mattogno/Kues/Graf, p. 1265). For the presumed gassing victims, half of that loss can be assumed, hence a loss of 33.5% of body fat or approximately (16.8 kg × 0.335 =) 5.6 kg, corresponding to (16.8 – 5.6 =) 11.2 kg of remaining body fat. Pressac and van Pelt agreed that the average weight of the claimed gassing victims was 60 kg,[35] quite in line with the average weight indicated above (65 kg).[36] This results in a total quantity of fat of (1,200 corpses × 11.2 kg/body =) 13,440 kg.

The specific weight of animal fat is 0.903 (Gabba, p. 406), therefore 13,440 kg of fat correspond to approximately 14,880 liters.

In an empty cremation pit, this fat theoretically would have been uniformly distributed at the rate of (14,880 L ÷ (41 m[37] × 8 m)] = some 45 liters per square meter, corresponding to a uniform layer of 4.5 centimeters. Due to the viscosity of liquid fat, if such an amount were poured evenly into a concrete container of identical size as the cremation pit here discussed, only a small part of it would flow into the outflow channel, and only if the bottom were slanted on both sides towards the channel.

But according to Müller, the bottom of the pit was flat, so only that part of the liquid fat which had flowed directly into the channel would have collected in it, i.e. (41 m × 0.275 m × 45 l/m² =) about 507 liters, about 253.5 liters per collecting well. If this measured 2 x 2 meters, therefore four square meters, the liquid fat would have filled it only up to a height of (0.2535 m³ ÷ 4 m² =) about 6 centimeters: how then would it have been possible to scoop it out with a bucket?

The dry wood required for the cremation of a 60-kg body amounts to around 160 kg, equivalent to about 304 kg of green wood.[38] Therefore, the fat had to flow through (1,200 bodies × 160 kg/body =) 192,000 kg of wood and, due to its high viscosity coefficient, would have largely adhered to it, therefore the quantity that would have poured into the two collection wells would have been enormously less than the 507 liters calculated above.

According to the manual of Eng. John H. Perry, the autoignition temperature of pork fat is 343°C (Perry, p. 1584). Other authors speak of a temperature of 355°C (DeHaan/Brien/Large, p. 235). At and above that temperature, fat will ignite by itself and will keep burning without the need for any ignition. But the flash point of fat is actually as low as 184°C (Perry, p. 1584). This means that, at and above this temperature, liquid fat emits vapors in such quantities that its mixture with air ignites in case of an ignition source, such as a spark, embers or an open flame. The autoignition temperature of dry wood, in comparison, is normally around 220-250°C (Giacalone, p. 1268) or 270°C (Richardson, p. 41). On the other hand, the minimum temperature required to form sufficient combustible gases from a corpse so the corpse actually ignites and burns is about 600°C. Below this temperature, the corpse will only carbonize (Kessler, p. 137). It is therefore impossible that liquid human fat collects at the bottom of a pit filled with a blazing wood fire hot enough to consume corpses. Any fat at the surface of a human corpse placed in a fire will ignite and burn off completely and instantly where it surfaces, without ever having the chance of reaching the bottom of the pit. But even if any drop of fat would ever fall to the bottom – which would be filled with red-hot glowing embers – it would burn off swiftly rather than flow anywhere.

No-less-absurd is Müller’s account of how this fat was scooped up by inmates (1979b, p. 136):

“As the heap of bodies settled, no air was able to get in from outside. This meant that we stokers had constantly to pour oil or wood alcohol on the burning corpses, in addition to human fat, large quantities of which had collected and was boiling in the two collecting pans on either side of the pit. The sizzling fat was scooped out with buckets on a long curved rod and poured all over the pit causing flames to leap up amid much crackling and hissing.”

Here the following remarks apply:

- Considering that the fire consisted of three superimposed layers of wood and corpses inside a pit two meters deep, it is clear that pouring oil, methanol and human fat onto the pyre’s surface would not have solved the problem of the lack of combustion air in the center layer and even less in the bottom layer of the pyre.

- These fuels would have already ignited on top of the first layer of wood and corpses, without giving a sensible heat input to the interior of the pyre.

- It must be kept in mind that we are dealing here with a cremation pit of at least 328 m², in which 1,200 corpses with 192 tons of dry wood were burning at a temperature of at least 600°C. How was it possible to get anywhere close enough to the edge of such a pit in order to throw a bucket of fuel into it, which would have caught fire already inside the bucket when merely approaching such an inferno? (This is particularly true for wood alcohol.)

- The boiling fat was allegedly collected with “a long curved rod”; since the pit was two meters deep, and the collection pit was even deeper (the bucket had to be immersed into the liquid fat), plus adding at least one and a half meters of handle so that a man operating it could do this while standing up, these rods had to be at least 4 meters long. If a bucket full of grease was attached to their end, it could have been lifted out only by holding the rod vertically, as illustrated in Document 23. This means that it would have been impossible to lift the bucket up from a distance. In practice, the fat-recovery worker would have remained for a few minutes at the very edge of the collection pit, merely two meters away from an 8-meter-wide wall of blazing flames. He would have been fatally burned.

In summary:

- The cremation pits did not exist.

- Even if they had existed, the recovery of human fat would have been impossible.

7.7. Further Cremation-Pit Fantasies

In this context, Müller inserts further fantasies, some plagiarized, some invented by himself.

From Höss ‘s statements he draws two other elements. First of all, with a slight retouch, the duration of the combustion in the pits (ibid., p. 138):

“The process of incineration took five to six hours.”

The only experimental data comparable with such an alleged mass cremation result from the burning of animal carcasses during the bovine spongiform encephalopathy epidemic (BSE) that struck England between 1986 and 2001, when in multiple places hundreds of animals were burned together on very long pyres. From the pyres described in detail it appears that the burning capacity of these fires was 8 kg of offal per square meter of fire in one hour (Mattogno/Kues/Graf, p. 1295). From this it can be deduced that a possible mass cremation of 1,200 corpses (72,000 kg), if considering a surface area of the pyre of (41 m[39] × 8 m =) 328 m², would have required ([72,000 kg ÷ [8 kg/m² × 328 m²] =) about 27 hours, or more than a day. It is therefore way longer than the five to six hours fantasized by Müller.

Model 4b of the coal-fired Kori Furnace for the destruction of slaughterhouse refuse (animal carcasses), the largest built by that company in the early Twentieth Century, took 13.5 hours to incinerate 900 kg of offal on a grate with the dimension 0.92 m × 2.9 m = 2.66 square meters.[40] This corresponds to [(900 kg ÷13.5 hrs) ÷ 2.66 m² =] 25 kg offal per hour and square meter. Müller’s cremation pit would have had a capacity of [(1,200 × 60 kg ÷ 6 hrs) ÷ (328 m²) =] 36.6 kg/hour per square meter, an astounding efficiency for a mere camp-fire-style pyre compared to a high-tech furnace!

Moreover, Tauber mentioned a much-more-realistic cremation duration of 48 hours in his deposition quoted earlier.

Müller also copied the following story from Höss (1979b, p. 137):

“Not infrequently the stoker team was reduced to half its number because fires could not be lit at night on account of black-out regulations.”

And here is what Höss wrote about that (Höss 1959, p. 215):

“Because of enemy air attacks, no further cremations were permitted during the night after 1944” (In the original “ab 1944,” meaning after the beginning of 1944)