Escape from Auschwitz

When it comes to Holocaust survivors we almost always tend to think about Jews. It can’t be helped actually as it is only Jews who appear on the media. But Jews were not the only ones sent to concentration camps. There were others as well. Today we will have a look at the testimony of one of them: Russian POW Andrei Pogozhev and his book Escape from Auschwitz (Pen & Sword, 2007).

When it comes to Holocaust survivors we almost always tend to think about Jews. It can’t be helped actually as it is only Jews who appear on the media. But Jews were not the only ones sent to concentration camps. There were others as well. Today we will have a look at the testimony of one of them: Russian POW Andrei Pogozhev and his book Escape from Auschwitz (Pen & Sword, 2007).

Pogozhev was sent to Auschwitz in October 1941 and then transferred to Birkenau. In November 1942 he managed to escape along with other prisoners and in 1965 he testified at the Auschwitz Trial. Let’s see what he witnessed regarding the exterminations.

It’s May 1942 and Pogozhev writes:

“It was in those days of pan Olek’s sickness, during visits from his numerous comrades, that I first discovered the Fascists had begun mass extermination – not only of prisoners but also of whole transports of people. Apparently the main extermination effort had shifted to Birkenau. They’d set up a ‘bath-house’ with pipes and a ‘shower’ grid and turned it into a gas chamber. People would be sent inside as if for a shower, then locked in and gassed. […] Fires cremating corpses after gassings in the ‘bath-house’ burned day and night at Birkenau. The fires and gas chambers were serviced by ‘Sonderkommandos’ [‘Special Units’ – trans.], specially formed from prisoners held outside the camp. No one knew exactly who they were.” (p. 97)

In 1942 there were no crematoriums in Birkenau and the only gas chambers according to the official story were Bunkers 1 and 2, or Little Red House and Little White House. Those were simple farmhouses outside the camp that had been converted into gas chambers. The corpses were then buried in pits. Pogozhev continues:

“Early July 1942. Birkenau is meshed with barbed wire, giving it the appearance of a huge spider’s web. I can see that a central road divides the camp in two. On the right sprawls a vast area under construction – the gouged ground ready for new drains and foundations. Meanwhile, prefabricated wooden huts stand already completed. On each of them shines a bright enamelled square containing large, black German script: ‘Pferde Baracken’ – ‘Horse Barracks’. On the left of the road I see the entrance to the women’s camp. Behind it, separated by barbed wire, is that of the men. In both these compounds big new structures have been built alongside the original brick barracks – they look just like the stables opposite. Now I look straight ahead: the only road crossing the camp from east to west terminates at a small grove immediately beyond its limits – the gas chambers and crematorium are situated there. This is the appearance of the Birkenau camp – ‘Auschwitz II’ – as our truck approaches. I am one of a large group of prisoners being driven from Central Auschwitz …” (p. 104)

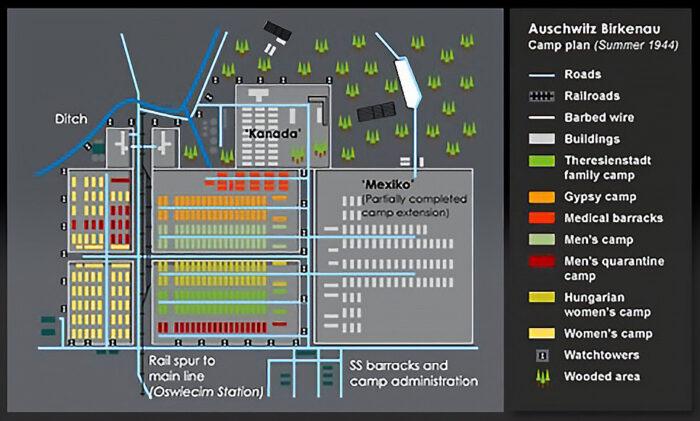

Here a map (of reality on the ground) is needed (North to the right):

As one would enter the camp, the women’s barracks was on the left of the road, but the men’s was on the right and not behind them. Also the grove was not visible from the main road, as it was a little further to the north. Referring to Bunker 2, Pogozhev places also a crematorium there, which he clearly distinguishes from the pits. For example:

“Away to our left, pyres were blazing deep in the Secret Grove. Further beyond, the crematorium was puffing out black smoke.” (p. 146)

He continues on the Sonderkommandos and their duties (pp. 115-122):

“The first Sonderkommando was formed at the end of 1941. It dug pits and carried out mass burials of bodies which, for some reason, hadn’t been taken to the crematorium. The burials were done in Birkenau. The second Sonderkommando was formed in March 1942. The men of the Sonderkommandos lived in isolation in the main camp, so no one could tell what they were doing in the forest, which grew right up to the camp grounds on its northwestern side. This secrecy led to the most incredible rumours – many of them contradictory. Even we, who’d grown used to atrocities, couldn’t believe these horror stories. Some rumours reached my ears when I was in the hospital, and there we had even less idea what was going on in Birkenau.”

But despite the secrecy he claims that:

“We quickly got acquainted with the Sonderkommandos and established good relations, not only with the Kapos of the teams, Weiss and Goldberg, but also with many ordinary crew members, who knew Polish and Russian.”

Now here’s what he claims he witnessed:

“On my return to Birkenau I’d been placed in the ‘Wascherei’ crew – in the washhouse. My duty was to hang out linen to dry after washing. The washhouse was situated in the south-western corner of the men’s camp, and watching over the drying linen I could see the adjacent grove. There, hidden behind the trees, I could make out silhouettes of people and the outline of a building. Black puffs of smoke – sometimes with bright tongues of fire – rose from this wooded area behind the camp day and night, dissipating in the air or settling on the ground as a grey coating. We nicknamed this place where pyres were burning the ‘Secret Village’ or ‘Secret Grove’.”

As we already saw in the map, the men’s camp was far from the grove. The only way to observe the site of Bunker 2 would be from the Sauna, which was behind the Kanada section and right next to the camp fence.

“At the end of July 1942 (or the beginning of August) both Sonderkommandos were merged and transferred to permanent accommodation in Birkenau. They were allocated a separate barracks-stable next to the fence. One end of the barracks was boarded up, the other faced a watch tower with an SS guard. Two men were chosen from the Soviet POWs for around-the-clock guard duty at the Sonderkommando barracks. To my great surprise one of those two happened to be myself. […] After a few days, in spite of the strict prohibition, we – and not only we – knew at first-hand what was happening in the ‘Secret Grove’ behind the camp; knew what the Sonderkommandos were doing and who was involved. The rumours were fully confirmed. One Sonderkommando – more numerous than the other – dug pits for mass graves – burying the evidence from pyres, gas chambers and crematoria. The other one serviced the first gas chamber, which was set up like a bath-house. Corpses were burned in the crematoria and on pyres. Everyone in the crew had his duties clearly spelled out. Each man knew what he was supposed to be doing. And no corpse would be burned (either in the crematorium or on the pyres) until it had undergone a thorough examination.”

Of course, there never was any crematorium there, proving that the rumors were not fully confirmed but fully worthless. And an even better example for this can be found a few paragraphs later:

“Here was an astonishing puzzle! We’d heard stories from Sonderkommando crewmen about how the gas dosage used for mass extermination – fatal for adults – sometimes failed to kill babies. Indeed, the younger they were, the more signs of life these infants displayed: they’d lose their voice and move their arms and legs silently. The Bull could casually finish those kids off with his pistol. There were cases when he and another SS-Mann took kids by the legs and threw them into the flames of a pyre. Few could witness this kind of sadism and remain sane.”

Summary

With a rather sensational book cover Pogozhev gives us a sensational account of his experiences but with surprisingly few details on the crimes committed. Whereas in other parts of the book there are tedious details about all sorts of things (even entire long verbatim dialogues between prisoners), the extermination part is much briefer despite his claimed close contact with the Sonderkommandos. Pogozhev is unaware of the term Bunker, their number, their internal arrangement, the gassing method, or the location or number of pits, not to mention the claim of a non-existent crematorium.

Finally, in the Epilogue he concludes:

“Auschwitz! The whole world knows that name: the place where Fascists exterminated 4 million people from all over Europe in four years.” (p. 167)

With rumors, contradictions, and horror stories, Andrei Pogozhev proves himself to be a worthy servant of the Motherland.

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 2018, Vol. 10, No. 2

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a