The Rise and Fall of Historical Revisionism following World War I

World War I was a tremendous disaster. While estimates vary, most experts agree that over 8 million combatants were killed and another 21 million were wounded.[1] The United States suffered over 116,000 deaths including those attributed to disease and accidents. For the US, it was the costliest war since the American Civil War. However tragic for Americans, US casualties were less than one-tenth those of the major European powers – Germany, Austria-Hungary, Russia, Britain and France.[2] Beyond its direct impact, its hatreds, machinations, secret deals, and even the terms of its peace resulted in the even more catastrophic Second World War. So staggering was the influence of the Great War that the entire power structure of the world began to shift.

Despite the calamity, there were those at the time who were resolutely idealistic about the causes it was said to have served. Colonel House assured President Woodrow Wilson that no matter what sacrifices the war exacted, “the end will justify them.”[3] Similarly, the catchphrase for the conflict “the war to end war” coined by British author and commentator H. G. Wells suggested a higher purpose, one that imparted meaning to the horrific death toll. Wells blamed the Central Powers for the coming of the war, and argued somewhat naively that the defeat of “German militarism” could bring about an end to war.[4]

Upon Germany’s conditional surrender, the victorious Allied Powers betrayed their lofty talk of a new world order of freedom, justice, and everlasting peace and refocused their energies on economic revenge. At the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, Germany was forced to accept guilt for the war’s origin and to pay nearly unlimited reparations. In addition, the German military was reduced to a domestic police force and portions of its land were commandeered to establish new nations in Eastern Europe. The territories of Alsace and Lorraine were ceded to France. German colonies were stripped away and handed over to the victorious Allies.

At the Conference, Wilson gained approval for his proposal for a League of Nations. While unhappy with the overall results, Wilson remained hopeful that a strong League could prevent future wars; he returned to the US to present the Treaty of Versailles to the Senate. The opposition from the Senate under the leadership of Henry Cabot Lodge was fierce. Lodge viewed the League as a supranational government that would impair the power of the American government to determine its own affairs. Other opponents believed the League was the sort of entangling alliance the United States had avoided since George Washington’s Farewell Address, which counseled against just such. Ultimately, the treaty would go down to defeat with Senate Democrats voting against it due to changes added by Lodge and the Republicans.[5]

It was around this time that several historical revisionists emerged on the scene. While “revisionism” has been applied to various periods and conflicts, it was the conclusion of the First World War that brought the term into general use. The revisionists were intent on understanding the real cause of the war and to “revise” the punitive Treaty of Versailles and especially the “War-Guilt Clause.”

In July of 1920, historian Sidney Fay wrote the first of a series of articles on the origins of the war.[6] Fay demonstrated the inequity of the war-guilt clause aimed at Germany. Not only had the Kaiser not decreed war upon the June 28, 1914 assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, he left on his planned vacation cruise on July 6, not expecting any “serious warlike complications.”[7] Fay concluded that a declaration of Austrian guilt would be far closer to the truth than the war-guilt clause of the Treaty of Versailles.[8]

Fay’s article had significant influence. The most important conversion however was that of Harry Elmer Barnes.[9] As a graduate student, Barnes had advocated intervention in Europe even prior to Wilson’s request that congress declare war. Historian Warren Cohen recounts that Barnes noted in a private correspondence that Fay’s article “undermined his faith in what his elders told him in much the same manner as had his earlier discovery of the non-existence of Santa Claus.”[10]

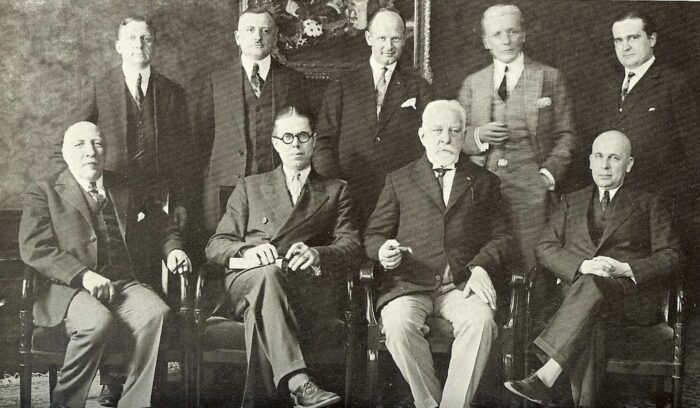

Seated: right to left: Alfred von Wegerer, Baron Rosen, Barnes. Standing: second from left: Friedrich Thimme, editor of Grosse Politik.

Source: Arthur Goddard ed., Harry Elmer Barnes: Learned Crusader (Colorado Springs: Ralph Myles, 1968).

Barnes’s discovery of Fay (a colleague at Smith College) would launch him into a lifelong battle for truth in history. Barnes recalls,

While I wrote some reviews and short articles dealing with the actual causes of the first World War between 1921 and 1924, I first got thoroughly involved in the Revisionist struggle when Herbert Croly of the New Republic induced me in March 1924, to review at length the book of Professor Charles Downer Hazen, Europe since 1815. This aroused so much controversy that George W. Ochsoakes, editor of the New York Times Current History Magazine, urged me to set forth a summary of Revisionist conclusions at the time in the issue of May, 1924. This really launched the Revisionist battle in the United States.[11]

Barnes was clearly influenced by the idealism of his age. His entry into the Revisionist controversy was fueled by more than simply historical accuracy for its own sake. Barnes was convinced that an accurate evaluation of the causes of World War One was necessary for peace in the 1920s and beyond. In fact one might say that the Revisionist cause for Barnes was “truth to end all war.”[12]

Following Barnes’s article in the New York Times Current History Magazine, scholarly periodicals and large publishing houses sought Revisionist material for publication. By the end of 1924, Professor Fay’s Origins of the World War, J.S. Ewart’s Roots and Causes of the Wars, and Barnes’s Genesis of the World War were all in print and defining the Revisionist position on the war in the United States.[13]

In his own assessment of the early days of Revisionism, Barnes wrote of the growing number of Revisionists around the world:[14]

“American Revisionists found allies in Europe: Georges Demartial, Alfred Fabre-Luce, and others, in France; Friedrich Stieve, Maximilian Montgelas, Alfred von Wegerer, Herman Lutz, and others, in Germany; and G.P. Gooch, Raymond Beazley, and G. Lowes Dickinson, in England.”

The interest in Revisionism spread from academic journals to the popular press. The Nation and New Republic were frequently publishing Revisionist articles. H.L. Mencken, editor of The American Mercury was delighted by Barnes’s work. In the April 1924 issue, Mencken published Barnes’s portrait of Woodrow Wilson. Controversialist Mencken gleefully commented that the article would rank Barnes alongside Judas Iscariot.[15]

Acceptance in the popular media was a major objective for Barnes. Barnes wrote:[16]

“The present writer has devoted his own efforts in the field of war guilt publications primarily to the task of bringing the facts revealed by scholars to bear upon public opinion and upon the policies and achievements of statesmen.”

For Barnes, only sufficient popular interest in Revisionism would be able to shift popular opinion and thereby result in policy change. Only such foreign-policy change would allow peace and goodwill among nations. In the preface to his In Quest of Truth and Justice, Barnes went so far as to write, “historical research is of little or no ultimate value unless its results have some actual bearing upon the improvement of the well-being of man in some aspect of his life.”[17] Barnes was therefore upset that his Genesis of the World War, despite becoming the Bible for American Revisionists, did not attain the distribution he had hoped for.[18]

It was now clear that Barnes viewed himself in a struggle with uncooperative booksellers, an uninformed public, and those historians who toed the official line – whom he would dub “court historians.” In 1928, Barnes vented:[19]

“A major difficulty has been the unwillingness of booksellers to cooperate, even when it was to their pecuniary advantage to do so. Many of them have assumed to censor their customers’ reading in the field of international relations as in the matter of morals. Not infrequently have booksellers even discouraged prospective customers who desired to have the Genesis of the World War ordered for them.”

Barnes described the early days of Revisionism as “precarious.” The shift from an academic to a public audience was sometimes met with fierce opposition. During a lecture he gave in Trenton, New Jersey, he was physically threatened by opponents in the crowd.[20] Barnes met with similar resistance in Massachusetts where his Genesis was even banned from the public library in Brookline.[21]

As the 1920s roared to a close the primary focus of the revisionist controversy shifted from the war-guilt clause to the question of why America had intervened in the conflict. Historians including C. Hartley Grattan and Charles Beard added their voices to the debate.

With the passage of time, emotions cooled about the Great War. Warren Cohen commented on revisionism of the late ‘20s:[22]

“What better way could there have been for the younger generation to undermine the pretensions of the previous generation than by demonstrating that the cause for which their elders had been willing to fight and die had been worthless, a fiction created by ‘myth-mongers.’”

It was little wonder that in 1935 when Walter Millis’s Road to War was published that it instantly became a best seller. Barnes commented on Millis’s achievement:[23]

“It was welcomed by a great mass of American readers and was one of the most successful books of the decade. Revisionism had finally won out.”

This fleeting victory of Revisionism may be most clearly illustrated by the anti-interventionist sentiment embraced by the American public in the 1930s and right through the run-up to the attack on Pearl Harbor. With the war-drums beating throughout Europe, the Revisionists valiantly attempted to point out the similarities to 1914. In a last-ditch effort to keep America out of the impending war, a group of scholars and personalities formed the America First Committee in 1940. Its membership included Harry Barnes, Charles Lindbergh, Herbert Hoover, Gerald Ford, Walt Disney, Henry Ford and John F. Kennedy among others.[24]

The Revisionists kept up their opposition to interventionism. Charles Beard wrote an article, “We’re Blundering into War” for The American Mercury in which he wrote:[25]

“The United States should and can stay out of the next war in Europe and the wars that follow the next war.”

C. Hartley Grattan argued:[26]

“No American shall ever again be sent to fight and die on the continent of Europe.”

As late as November 1939 (two months after the German invasion of Poland), Barnes warned:[27]

“The moment we join the war, the New Deal and all its promises of a ‘more abundant life’ will fold up, as did the New Freedom of Woodrow Wilson in 1917.”

On December 9, 1941, two days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the America First Committee ceased to exist. Despite the efforts of the Revisionists, historical revisionism proved not a powerful enough force to prevent another world war.

Since World War Two, public attitudes on the interwar Revisionist controversy have been largely reversed. The battle for a proper revision of the causes of World War One was not lost because of new evidence, but rather because of new attitudes shaped by events, real or contrived, of World War Two.[28]

World War Two was initially a disaster for Revisionism and for the world. Cohen notes that the “revisionist interpretation of American intervention in World War I is in disrepute, the revisionist studies of America’s road to war from 1914-1917 are considered of little use to students of American diplomatic history.”[29]

Rather than attacking the Revisionist interpretation of World War One, the argument could be made that the Revisionists’ efforts failed for being “too little too late.” Had America not intervened, had the war-guilt clause of Versailles not been dictated, the destruction of the Second World War might never have happened. In his final article on World War One, Barnes theorized:[30]

“Had we remained resolutely neutral from the beginning, the negotiated peace would probably have saved the world from the last two terrible years of war. Whenever it came, it would have rendered unnecessary the brutal blockade of Germany for months after the World War, a blockade which starved to death hundreds of thousands of German women and children. This blockade was the one great authentic atrocity of the World War period. In all probability, the neutrality of the United States would also have made impossible the rise of Mussolini and Hitler – products of post-war disintegration – and the coming of a second world war.”

Today the conduct of interventionism has resulted in an American empire that stretches beyond its means and stirs agitation and animosity around the globe. The media and an ignorant but well indoctrinated public mock the very ideas of “isolationism” and revisionism but are left wondering why American troops are engaged and dying in perpetual wars for perpetual peace. The idealism of the 1920s has been exchanged for a pessimism that fails to even consider ways to address the decline of a once-great nation.

All would do well to recall that the historical revisionist movement set out to prevent the bloodshed of a second world war and all the wars that followed. The revisionists of World War One should be remembered as heroes who set out to discredit misleading myths that ultimately led to more war and hatred among nations, and honored by the revival and continuation of their crucially noble struggle.

Notes:

| [1] | Revisionist scholar Harry Barnes cited a slightly higher figure for known dead. In his article “The World War of 1914-18” he cites some 9,998,771 dead and another 6,295,512 seriously wounded and another 14,002,039 otherwise wounded. See Willard Waller, ed., War in the Twentieth Century (New York: Revisionist Press, 1974 [1940]), pp. 92-93. |

| [2] | WWI Casualty and Death Tables. Online: http://www.pbs.org/greatwar/resources/casdeath_pop.html |

| [3] | Ralph Raico, Great Wars and Great Leaders: A Libertarian Rebuttal (Auburn, Ala.: Ludwig Von Mises Institute, 2010), p. 43. |

| [4] | Online: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_war_to_end_war |

| [5] | The Treaty of Versailles and the League of Nations. Online: http://www.ushistory.org/us/45d.asp |

| [6] | Sidney Fay, “New Light on the Origins of the World War, I. Berlin and Vienna, to July 29,” American Historical Review, XXV, pp. 616-639. |

| [7] | Warren I. Cohen, The American Revisionists: The Lessons of Intervention in World War I (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967), p.36. |

| [8] | Ibid. |

| [9] | Ibid. |

| [10] | Ibid. |

| [11] | Harry Elmer Barnes, “Revisionism and the Promotion of Peace,” in Barnes against the Blackout: Essays against Interventionism (Costa Mesa, Calif: Institute for Historical Review, 1991), p. 278. |

| [12] | Cohen, op. cit., p. 39-40. |

| [13] | Barnes, op. cit., “Revisionism and the Promotion of Peace,” p. 278. |

| [14] | Ibid., pp. 278-279. |

| [15] | Cohen, op. cit., p. 65. See Barnes, “Woodrow Wilson,” The American Mercury, I (April, 1924), pp. 479-490. |

| [16] | Harry Elmer Barnes, In Quest of Truth and Justice: De-Bunking the War Guilt Myth (Colorado Springs: Ralph Myles, 1972 [1928]), p. viii. |

| [17] | Ibid. |

| [18] | Ibid., p. ix. |

| [19] | Ibid., p. x. |

| [20] | Barnes, op. cit., “Revisionism and the Promotion of Peace,” p. 279. |

| [21] | William L. Neumann, “Harry Elmer Barnes as World War I Revisionist” in Harry Elmer Barnes Learned Crusader ed. Arthur Goddard (Colorado Springs: Ralph Myles, 1972), p. 275. |

| [22] | Cohen, op. cit., pp. 85-86. |

| [23] | Barnes, op. cit., “Revisionism and the Promotion of Peace,” p. 279. |

| [24] | America First Committee. Online: http://www.nndb.com/org/039/000057865/ |

| [25] | The American Mercury, XLVI (April, 1939), p. 395. |

| [26] | Cohen, op. cit., p. 210. |

| [27] | Harry Elmer Barnes, “When Last We Were Neutral,” The American Mercury, XLVIII (November, 1939) p. 277 quoted in Cohen. p. 216. |

| [28] | Cohen, op. cit., p. ix. |

| [29] | Ibid., p. 240. |

| [30] | Harry Elmer Barnes, “The World War of 1914-1918” in War in the Twentieth Century, ed. Willard Waller (New York: Revisionist Press, 1974 [1940]), p. 97. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 6(3) 2014

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a