Being Jewish: Remembering the Holocaust

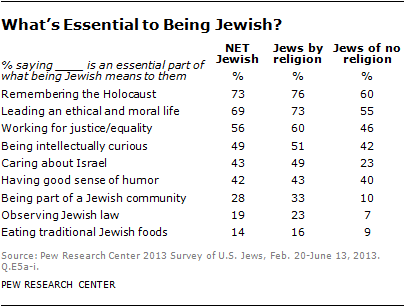

In 2013, the Pew Research Center conducted a major survey, A Portrait of Jewish Americans, among American Jews to ascertain various group characteristics and opinions. In that study’s Chapter 3, “Jewish Identity” (tinyurl.com/ok8jp4d), a striking finding emerged that must be of great interest to Holocaust revisionists everywhere: “Remembering the Holocaust” is an important element of “being Jewish” to more Jews than is any of a list of eight other surveyed elements, including “Observing Jewish law” and even “Caring about Israel” (see table on next page). This finding could go a long way toward helping revisionists understand the common and vociferous opposition evinced by many Jews against revisionism.

As for revisionism, it is by no means our position that the Holocaust should be forgotten (much less, of course, “denied”). To the contrary, revisionists tend to remember the Holocaust far more, and better, than the modal American or Jew. Revisionists advocate a more-accurate—more-measured, in two senses of the word—remembering of the Holocaust, one that, among other things, repositions it better in the context of the times, places and people involved in it, as well as the times, places and people of the present. Some revisionists might favor some toning-down of remembrances of the Holocaust along with extensive reshaping of the factual assertions involved in the more-common manifestations of the sentiment, and above all, perhaps, complete abandonment of all imputation of guilt to any person who did not take an active, personal hand in the commission of atrocities. To start with, this would instantly exonerate anyone and everyone who had not yet been born at the time, along with virtually everyone who was not in Europe during the period in question.

Returning to the central sentiment of Jewish identity, “remembering,” strictly defined, is an internal feeling, not an external demonstration, and much less the subject of laws such as France’s Loi Gayssot providing criminal penalties for any person assertively failing to “remember” the subject in legally permissible terms. “Remembering” in this sense is certainly not what the word implies in the survey question, nor in the meaning intended by most of those responding to the survey. The word “Celebrating” would serve better except, of course, for the connotation that word has of a happy observance of a positive occasion. Had the question been worded “Defending, perpetuating and enforcing the story of the Holocaust,” the response would have been of much greater pertinence to revisionist concerns.

Returning to the central sentiment of Jewish identity, “remembering,” strictly defined, is an internal feeling, not an external demonstration, and much less the subject of laws such as France’s Loi Gayssot providing criminal penalties for any person assertively failing to “remember” the subject in legally permissible terms. “Remembering” in this sense is certainly not what the word implies in the survey question, nor in the meaning intended by most of those responding to the survey. The word “Celebrating” would serve better except, of course, for the connotation that word has of a happy observance of a positive occasion. Had the question been worded “Defending, perpetuating and enforcing the story of the Holocaust,” the response would have been of much greater pertinence to revisionist concerns.

At the same time, the number of respondents choosing an item so reworded might be considerably less than the number who chose the item as actually worded. It most emphatically does not follow that every Jew, or even most Jews to whom “Remembering the Holocaust” is an important part of Jewish identity in fact wishes to defend, perpetuate or enforce the regnant story of the Holocaust, especially where non-Jews happen to be concerned. And, as the survey explores in considerable detail in other sections, being (or being seen as) Jewish itself is not necessarily of paramount importance to every Jew, so in those quite numerous cases, again, the force behind the “remembering” is diminished.

It is impossible to disentangle opposition to Holocaust revisionism from the assertion of Jewishness, nor from the philo-Semitism displayed by large segments of the American population. Every revisionist, particularly those such as myself who have numerous Jewish friends and relatives, must develop and constantly heed an exquisite sensitivity toward the indoctrination that American Jews and non-Jews alike have been subjected to all their lives teaching them not only the particulars of the (literally) unbelievable atrocities visited by Germans upon Jews during and prior to World War II, but also to impute equally evil motivations to any person who would express doubt as to any of those particulars.

For my part, when I am in the company of a Jew(s) to whom I ascribe good will and intelligence (a large proportion of the Jews whom I know well enough to make such judgments), I speak of my interests in The Subject virtually the same way I would with any group of similarly disposed Gentiles. Far be it from me to deny my (Jewish) interlocutors credit for rising above the tribal prejudices among which each of us was raised in one way or another. Obviously, when I am careless or unlucky, my approach raises disapproval along with the expected disagreement—reflexive reactions precede more-thoughtful ones in the best of us, to say nothing of those of us who are more typical of our species. In virtually every such case, especially as my companions themselves recognize that their initial reactions might not withstand dispassionate contemplation, I’m able to refine and define not only my exact views of the matters at hand, but also, very importantly, the specific sentiments that underlie my inquiries and conclusions arising therefrom.

On the recent occasion of the “70th anniversary of the Holocaust,” the Pew Center published on its Fact Tank webzine an article (tinyurl.com/ouy8zdj) titled “70 years after WWII, the Holocaust is still very important to American Jews,” a headline reflecting a profound misapprehension of the history of “Holocaustography” in the US and around the world. The undoubtedly young headline writer simply didn’t realize that the Holocaust was an almost-undetectably minor subject among Jews and Americans alike sixty years ago and much of the time since, as I well remember myself. In Israel in particular, the very numerous real and false Holocaust “survivors” were often maligned with the nickname “soap,” recalling the myth of Nazis making soap from the fat of boiled-down Jewish corpses. Survivors there and then were, with some justification, suspected not just of seeking unearned sympathy, but further of collaboration or even worse offenses enabling their survival. What a difference a half-century makes!

It simply will not do for revisionists to suppress or misrepresent their views on Holocaust history in the company of most American Jews—to do so is an insult to their intellects and integrity. After all, thoughtful Jews are very much to be found in the ranks of revisionists ourselves, although they might be granted a pass for being discreet among their co-religionists.

But an awareness of the findings of the Pew survey should not be overlooked, either. Even if revisionists do not regard Jews or Jewishness to be enemies of our beliefs, it should be kept in mind that many Jews are taught in no uncertain terms that revisionism is, indeed, their enemy. This trend is as likely to become worse in the near future as it is to abate, which latter it certainly must do in the (very) long term.

Bibliographic information about this document: Smith’s Report, No. 215, September 2015, pp. 1-3

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a