Could Hitler Have Won? A Thoughtful Look at the German-Soviet Clash Reassesses the Second World War

Book Review

Hitler’s Panzers East: World War II Reinterpreted, by Russell H.S. Stolfi. University of Oklahoma Press, 1991. Hardcover. 280 pages. Photographs. Maps. Notes. Bibliography. Index.

Joseph Bishop studied history and German at a South African university. Currently employed in a professional field, he resides in the Pacific Northwest with his wife and three children. An occasional contributor to a variety of periodicals, this is his first contribution to the Journal.

How close did Hitler come to winning World War II? What was the real turning point in the war, and why? In this pathbreaking revisionist study, Professor Stolfi provides some startling answers to these questions.

If Hitler had played his cards just a bit differently, contends the author – a professor of Modern European History at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California – he could have won the war. German forces came very close to defeating the Soviet Union in 1941. Because Britain alone posed no mortal threat to German power, the defeat of Soviet Russia would effectively have ended the war, resulting in German hegemony over all of Europe. The result would have been a drastic change in the course of world history.

When Americans think of the Second World War, it is understandably most often in terms of the United States role, such as in the D-Day invasion or the war in the Pacific against Japan. Often overlooked or improperly appreciated is the Russo-German conflict, even though it was on the eastern front that most of the fighting took place, and where the war was really decided. The war’s greatest land battles were waged in the east, dwarfing those on other fronts. Three out of five German divisions were destroyed by Soviet forces. By the time American troops landed in France in the June 1944 D-Day invasion – less then a year before the end of the war – the outcome had already been determined.

Treacherous Surprise Attack?

According to the generally-accepted view of this chapter of history, Hitler’s June 22, 1941, “Barbarossa” strike against the Soviet Union was a treacherous surprise attack against a peaceable and fearful neighbor. This view (“proven” at the Nuremberg Tribunal) holds that an insatiably imperialistic Hitler struck against Soviet Russia as part of his mad effort to “conquer the world.”

The truth, Stolfi establishes, is quite different. A mass of evidence, including recently uncovered documents from Russian archives, shows instead that the massive Soviet forces encountered by the German invaders right on the western border areas were poised for their own imminent offensive. Writes Stolfi (p. 204):

Hitler seems barely to have beaten Stalin to the punch … Recently, published evidence and particularly effective arguments show that Stalin began a massive deployment of Soviet forces to the western frontier early in June 1941. The evidence supports a view that Stalin intended to use the forces concentrated in the west as quickly as possible – probably about mid-July 1941 – for a Soviet Barbarossa. Statements of Soviet prisoners also support a view that the Soviets intended an attack on Germany in 1941. The extraordinary deployment of the Soviet forces on the western frontier is best explained as an offensive deployment for an attack without full mobilization by extremely powerful forces massed there for that purpose.

Stolfi’s view is consistent with the detailed revisionist study by Russian historian Victor Suvorov (Vladimir Rezun), Icebreaker: Who Started the Second World War, as well as research by several German historians.

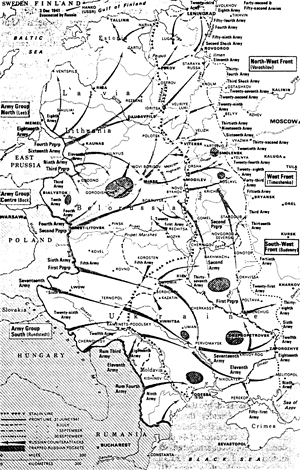

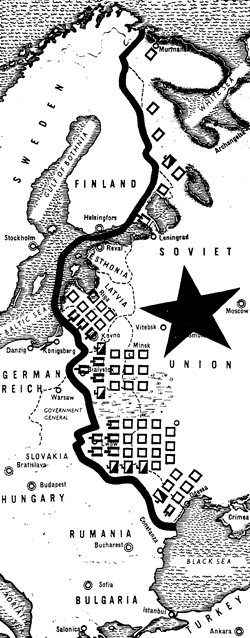

By mid-June 1941, Stalin had concentrated enormous Red-Army forces on the western Soviet border, poised for a devastating attack against Europe. This diagram appeared in the English language edition of the German wartime illustrated magazine Signal.

Hitler’s ‘Greatest Blunder’?

Hitler’s “many detractors,” writes Stolfi (p. 207), often point to his decision to invade Soviet Russia as his greatest blunder. Stolfi emphatically disagrees (pp. 206, 208):

The decision to attack the Soviet Union was the correct decision for Germany in July 1940, for whether or not Britain was defeated in the autumn of 1940, Russia would have to be attacked in the campaign season of 1941 … Hitler made the correct decision at the right time to attack the Soviet Union as early as practicable in 1941. It was the most significant move in his political career. Making that decision in July 1940, he gave Germany a clear chance to win the Second World War in Europe.

As history is revised in accord with the facts, Hitler the insane aggressor becomes Hitler the defender of Germany and Europe, who carried out a preemptive strike against a real aggressor, Stalin, to save his homeland and the West from Soviet tyranny.

Catastrophic Miscalculation?

Other widely-accepted views hold that Hitler, in launching his attack against Russia, grossly underestimated Soviet military capabilities while at the same time overestimating his own, that exhausted German military forces suffered a logistical breakdown within months of the attack, and that road, terrain, and weather conditions precluded a German victory. Stolfi persuasively refutes such explanations as the assumptions of convenient historical hindsight (“it happened that way because it could not have happened any other way”).

German planners, he argues, accurately anticipated both the military strength of their Soviet adversaries, as well as the adverse campaigning conditions. German forces were trained and prepared for precisely the campaign that unfolded, and consequently not only kept to their timetable objectives but in many cases exceeded them. Germany’s panzer and motorized formations, along with her hard-marching infantry troops, rapidly traversed the primitive roads and terrain with no undue difficulties.

Within just a few weeks after launching “Barbarossa,” German forces had succeeded in capturing or destroying eight of nine Soviet field armies, and had essentially shattered the vast Soviet forces facing “Army Group Center.” By July 3, 1941 – just eleven days after launching the Barbarossa attack – the Soviets had lost 935,000 men (killed, wounded or captured), whereas Germans losses were just 54,892.

On a 1900-mile front stretching from the Arctic Circle to the Black Sea, German and allied troops fought Soviet forces in the greatest clash of arms in history. As this map shows, German forces were brought to a halt just outside Moscow in December 1941. Hitler's objective was a line stretching from Archangel to Astrakhan.

Germany’s military formations and materiel were still relatively intact in mid-August, and her engineers were rapidly adapting the Soviet rail network to conform with the European gauge width. Meanwhile, Moscow’s defenses were still chaotic and disorganized. Almost to a man Germany’s officer corps and higher level military leaders were confident that they would soon capture Moscow in a final advance, and win the war in Russia. Even many Russians shared this view. Extensive interrogations of captured Russian officers and troops revealed a widespread belief that the Germans would definitely take Moscow after one more great battle.

Logistically and psychologically, contends Stolfi, German forces were more than adequately poised for a final, successful drive against Moscow – which was the hub of the Soviet Union’s road and rail communications system as well as by far the most important Soviet industrial center. Even taking into account the weather conditions, Stolfi convincingly posits that German forces could have reached their Moscow objective, and even beyond – before the onset of the rain and mud season in mid-to-late October.

A Fatal Decision

What went wrong? Stolfi points to Hitler’s momentous decision in mid-August to divert German forces southward. Overruling objections from several of his generals, Hitler ordered Army Group Center to veer south to first strike into Ukraine and Crimea, smashing the remaining Soviet forces there and capturing major economic and strategic objectives, before resuming the drive on Moscow.

This move, Stolfi asserts, fatally delayed the German offensive and enabled the Soviet forces before Moscow to regroup and strengthen the capital’s defenses. When the Germans resumed the advance against Moscow in early October, they achieved great initial victories, but were also forced to contend with the debilitating autumn rain and mud, as well as shorter daylight hours for campaigning. In early December the German offensive ground to a halt in the Moscow suburbs.

Hitler’s decision in August 1941 to strike south before continuing the drive east, Stolfi believes, was the critically fatal decision of the war. This, and not the later, “anti-climactic” battles of Stalingrad, Alamein, or Kursk, was the war’s real turning point. “…The German failure to seize Moscow in August 1941,” he writes (p. 202), “was the turning point in the Russian campaign. After that, the Germans faced certain defeat in the Second World War, an outcome that altered fundamentally the course of events in this century.”

As impressive as they are, Stolfi’s arguments for this thesis are inconclusive. If Moscow had fallen, would Stalin and the Soviet leadership really have lost popular credibility and authority? Would the Soviet people and troops have become too demoralized to carry on, leading to general military collapse?

Because the nature of the Soviet system and its military was dramatically different than that of Germany’s earlier adversaries, the loss of the capital may not have been as critical as Stolfi contends. Moscow’s fall may not have rendered untenable the strategic position of the strong Soviet forces still fighting in Ukraine or the Leningrad region. A continued German drive eastward might have dangerously exposed the flanks of Army Group Center to crippling attacks from the still formidable Soviet forces in the north and south. Hitler himself believed that Moscow’s capture would not have ended Soviet resistance, but would only have meant a continuation of the war further east or south.

During a visit with some of his Eastern front troops early in the “Barbarossa” campaign, Hitler pauses to speak with a soldier in a back row. Unlike Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill, the German leader quite frequently visited his front-line troops.

Strategic Considerations

Because he did not believe that his generals understood Germany’s immense economic and strategic requirements, or the critical economic and strategic importance of the eastern campaign, Hitler rejected their pleas to push on to Moscow in August 1941.

In this southward drive German forces seized Ukraine, the Donetz basin, and the Crimea, destroying or capturing immense Soviet forces. Added to the earlier captures of Belarus (White Russia), the Baltic lands, and most of European Russia, these new gains denied to the Soviet opponent much of its huge population base as well as a large portion of its resources and industry. These gains deprived the Soviet colossus of a great deal of its ability to mobilize troops and materiel for war, while at the same time greatly strengthening Germany’s economic base and war-making ability.

As it was, Germany’s capture and occupation for several years of vast Soviet territories, with their enormous economic resources, did indeed enable her to resist the Soviet colossus for much longer than many expected. These victories also provided Germany with at least the possibility of victory. In Hitler’s War (London: Focal Point, 1991; pp. 404–405), historian David Irving explains the German leader’s reasoning:

It was most urgent in his [Hitler’s] view to deprive Stalin of his raw materials and arms industry. Besides, a rapid advance southward would encourage Iran to resist the Anglo-Russian invasion which he already knew was in the cards; in any case, he wanted the Crimea in German hands: it was from Crimean airfields that Russian bombers had recently attacked Romania … The army high command continued stubbornly with its plans to attack Moscow. Only later was it realized that Hitler’s strategy would have offered the better prospects … “Today I still believe,” Göring was to tell his captors, “that had Hitler’s original plan of genius not been diluted like that, the eastern campaign would have been decided by early 1942 at the latest.”

Other Imponderables

Not discussed in Stolfi’s study are additional indeterminate factors, such as the arrival several weeks earlier than usual of the Russian winter of 1941–42, a winter that was possibly also the harshest in several decades. Further imponderables include the reaction of Britain and the United States to the fall of Moscow. We simply do not know whether the fall of the Soviet capital would have moved Britain finally to acknowledge German hegemony on the continent and bring her to the negotiating table, or induce the United States to discontinue military aid to Soviet Russia.

Nor does Stolfi deal with the impact of the massive and rapidly increasing American economic and military aid to the Soviet Union, or its possible effect on the Soviet ability to wage war if the Germans captured Moscow.

As it was, the deliveries of US military supplies already in 1941 may have given the Soviets a psychological and material boost sufficient to insure their survival in late 1941.

Historical ‘What Ifs’

Stolfi convincingly demonstrates that the German forces had the capability to at least capture Moscow within this time frame. What will always remain unknown is whether the fall of that city would have automatically led to the collapse of the other fighting fronts in Russia and a German victory, or would merely have been the capture of another major Soviet city in a continuing war.

However fascinating, historical “what ifs” such as Stolfi’s can be misleading. In contrast to his provocative thesis, consider this possible scenario: Hitler seizes Moscow in September 1941, but his victorious Army Group Center is threatened with encirclement by the vast remaining Soviet forces deployed in the north and especially the south, striking pincer-like at its flanks. To avoid a catastrophic encirclement, Hitler is forced to withdraw and relinquish Moscow – and a 1941 victory over the Soviet Union eludes him. Decades later, historians assail Hitler’s decision to take Moscow directly, arguing that if only he had struck south first, destroying the large Soviet forces there, and seizing the economic wealth of that region, before striking against Moscow, he would have won the campaign and the war.

Seemingly endless columns of Soviet troops captured in the great military victories during the first months of Germany's “Barbarossa” offensive are marched to internment camps behind the lines.

‘Siege Mentality’

Stolfi contends that Hitler made decisions in keeping with a “siege mentality” based on Germany’s harrowing First World War experience of geographic encirclement and economic strangulation. Hitler was acutely conscious of the severe limits to his nation’s natural resources and its disadvantageous geographical place in the world. He thus made military decisions with thoughtful regard for these paramount economic and territorial considerations. Hitler, writes Stolfi (p. 211), “was a popular dictator, extraordinarily concerned about his personal popularity and the potential strain on it from the economic rigors of war. He was an uncompromising idealist who saw Germany secure as a great power only by the acquisition of enough contiguous space to ensure economic autarky [self-sufficiency].”

In this regard Stolfi cites (p. 221) Hitler’s “Operation Barbarossa” directive of December 18, 1940. “The final objective of the operation,” Hitler ordered, “is to erect a barrier against Asiatic Russia on the general line Volga-Archangel [Arkhangelsk],” essentially “a line from which the Russian air force can no longer attack German territory.” What these words show, comments Stolfi, “is Hitler’s astoundingly conservative cast of mind, pivoting around a Germany-under-siege mentality.”

While Hitler stated his intention “to crush Soviet Russia in a rapid campaign,” and anticipated a quick Russian campaign that would be concluded by the late summer or fall of 1941, he also foresaw German rule clearly limited to the territory west of the Volga river, apparently accepting a residual Soviet regime to the east. Hitler envisioned a mighty, economically self-sufficient European “fortress,” under Germany hegemony, that would be able permanently to withstand a siege by residual Soviet, British, or American forces.

As further evidence of this mentality, Stolfi cites (p. 222) Hitler’s words at a high-level conference on November 29, 1941 – that is, at a moment when Moscow seemed ready to fall: “If we accomplish our European missions, our historical evolution can be successful. Then in the defense of our heritage, we will be able to take advantage of the triumph of our defense over the tank to defend ourselves against all attackers.” To help insure a successful defense of this projected eastern barrier, at this meeting Hitler ordered a shift in production toward antitank weapons over tanks. Hitler’s words at this conference, Stolfi comments (p. 222), “reveal an outlook one can characterize as concerned and cautious, representing siege thinking.”

Stolfi rejects the conventional propaganda image of Hitler as a largely incompetent dictator driven by hysterical hate and limitless lust for conquest. Actually, the author shows, this “concerned and cautious” leader acted with intelligence and reason, giving thoughtful consideration to economic objectives and the capture of strategic areas to insure his nation’s survival. It was the often cautious Hitler who had to restrain his generals, and not the reverse.

Sense of Urgency

The author contrasts this “siege thinking” with another aspect of Hitler’s temperament – a remarkable sense of urgency. Stolfi stresses (pp. 205–206, 203–204):

Hitler’s political forcefulness and sense of timing to get things done quickly to reach his foreign policy goals were important elements in the remarkable string of foreign policy and war successes from 1935 to 1940.

… Hitler cannot be faulted for lack of forcefulness or pace in his foreign policy; rather, he was a paragon of concentration, force, and speed. While making his foreign policy decisions he was assailed by fears, doubts, and procrastination, but he always overcame them. He impressed his decisive will on his foreign policy opponents from 1935 to August 1939 and achieved every goal without recourse to war… When Hitler reached his greatest decision [to attack Soviet Russia], it was with the same forcefulness and sense of urgency that characterized the past.

Hitler’s Blitzaussenpolitik [lightning swift foreign policy] advances and apparent lightning wars complemented one another … Regarding his decision to attack the Soviet Union, one marvels at the consistency of pattern, the fanatical sense of urgency, and the sensitivity of the policy to time … Hitler must be seen as attacking the Soviets to achieve the National Socialist Weltanschauung (world view) and end the war in Europe by seizing European Russia and smashing Soviet communism.

Other Possible Turning Points

Unlike Stolfi, some historians maintain that Germany could still have won the war in the East in 1942 or even as late as mid-1943. Some scholars point to the German defeat at Stalingrad (February 2, 1943) as the war’s turning point, at least psychologically. Yet even as late as July 1943 Germany was still able to seize the strategic initiative in launching the “Operation Citadel” offensive at Kursk-Orel, a clash that was to prove the greatest tank battle in history.

In Scorched Earth (London: 1970), historian Paul Carell contends that a German military victory against the Soviet Union was still possible as late as the summer of 1943. German forces, he argues, could have prevailed at Kursk, thus retaining the strategic initiative to pursue further victories, but were disengaged prematurely. Carell explains (pp. 87–95):

Just as Waterloo sealed the fate of Napoleon in 1815, putting an end to his rule and changing the face of Europe, so the Russian victory at Kursk heralded a turning-point in the war and led directly, two years later, to the fall of Hitler and the defeat of Germany, and thus changed the shape of the entire world. Seen in this light, Operation Citadel was the decisive battle of the Second World War.

Russian women are pressed into service digging anti-tank trenches outside Moscow as part of the effort to defend the Soviet capital against approaching German forces, summer 1941.

Dispelling Propaganda Myths

Hitler’s Panzers East is a solid, well-referenced work with an excellent bibliography that makes good use of archival and interview sources. Written in a clear, dispassionate style, this balanced book is refreshingly free of the all-too-common gratuitous Hitler-bashing or Germanophobia. Unfortunately, numerous textual and date errors show that the manuscript was not carefully proofread. Brought out by a respected academic publisher, professor Stolfi’s book has deservedly earned respect and acclaim. Military History (Oct. 1993) lauded it as “reasoned, intelligent and well-informed,” and Publisher’s Weekly called it “a credible reevaluation of the war.” It received reserved commendation from the American Historical Review (June 1993).

While it focuses on the eastern campaign, Hitler’s Panzers East is a useful antidote to the seemingly endless blizzard of polemical nonsense that often passes for reputable history about the Second World War. Stolfi deftly demolishes many common propaganda myths about Hitler and wartime Germany’s military leadership, as well as widely accepted misconceptions about Soviet policy and intentions.

This book further serves to help discredit popular myths, especially widespread in the United States, based on propaganda “documentaries” and such slanted historical works as William Shirer’s bestselling Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Finally, Hitler’s Panzers East points up the yawning chasm between the popular Hollywood image of Hitler and the Third Reich, and the growing consensus of objective 20th-century historians. It is another revisionist milestone that shows how much progress has been made, and how much more work still needs to be done.

“A good character carries with it the highest power of causing a thing to be believed.”

—Aristotle, Rhetoric

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 15, no. 6 (November/December 1995), pp. 38-44

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a