German Nationalist Jews During the Weimar and Early Third Reich Eras

The presence of many Germans of Jewish descent in the German armed forces of the Third Reich comes as a revelation to many. The recent book Hitler’s Jewish Soldiers: The Untold Story of Nazi Racial Laws and Men of Jewish Descent in the German Military,[1] by Bryan Mark Rigg, shows that up to 150,000 part-Jews fought for the Third Reich, including some of high rank.

These part-Jews or Mischlinge were part of a graduated classification of those of Jewish descent under the Reich Citizenship Law, which determined to what extent Jewish heritage affected one’s rights under the National Socialist regime. The designation of several types of Mischlinge was proclaimed in 1935. Half-Jews who did not follow Judaism or who were not married to a Jewish person on September 15, 1935, were classified as Mischlinge of the first degree.One-quarter-Jews were Mischlinge of the second degree. While the Yellow Star of David was required to be worn by Jews after September 14, 1941, Mischlinge were exempt.[2]

However, less recognized than the Mischlinge and Hitler’s so-called “Jewish soldiers” were the Jews, including many World War I Jewish veterans, who were German nationalists.

Marxists and Zionists Were Aberrations among German Jews

German Jews were the most assimilated of Europe’s Jewish populations. Most identified themselves entirely with the German nation, people, and culture.[3] Jews who were Marxists and subversives of other types, disparaging not only Germany, but also traditional morality, were among the most conspicuous and vocal of Germany’s Jews. Hence, they were ready subjects for the anti-Semitic writers and agitators in Germany who could point to Jews being in the forefront of a myriad of anti-German movements and ideologies that proliferated especially in the aftermath of World War I.

Many Jews fought with distinction during World War I. Of the 96,000 Jews who fought in the Germany army, 10,000 were volunteers. 35,000 Jews were decorated, and 23,000 were promoted. Among the 168 Jews who volunteered as flyers, Lieutenant D R Frankl received the Pour le mérite. Twelve thousand Jewish soldiers died in combat.[4] It is from among such Jews that a new seldom-recognized German-Jewish nationalist movement emerged.

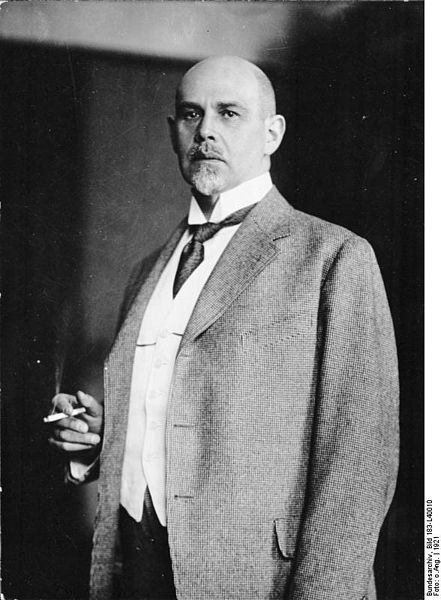

The prominent Jewish businessman and foreign minister (1922) Walther Rathenau urged German Jews to become German and “not to follow the flag of their philo-Semitic protectors any longer.” There should be “the conscious self-education and adaptation of the Jews to the expectations of the gentiles.” He further repudiated “mimicry” and sought rather “the shedding of tribal attitudes which, whether they be good or bad in themselves, are known to be odious to our countrymen, and the replacement of these attributes by more appropriate ones.” The result should not be “Germans by imitation” but “Jews of German character and education.” Furthermore, he advocated a willed change in the Jewish physiognomy and way of bearing, to physically renew the Jews over the course of several generations, away from the “unathletic build, narrow shoulders, clumsy feet, and sloppy roundish shape.” In character the German Jews, noted Rathenau, rarely steered a middle course between “wheedling subservience and vile arrogance.”[5]

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-L40010 / CC-BY-SA [CC-BY-SA-3.0-de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons

From conservative opinion, Oswald Spengler regarded Rathenau with esteem, a regard that Rathenau returned.[7] Rathenau’s assassination by members of the Rightist paramilitary Freikorps in 1922 represents perhaps the first shot in the tragedy of German Jews who regarded themselves above all as Germans during the Weimar and Third Reich eras. Jews being widely associated with Communism and the new Soviet Union, it was assumed that Rathenau’s signing of the Treaty of Rapallo with the Soviet Union was a conspiracy between Jewish capitalists (represented by Rathenau) and Jewish Bolsheviks. Rather, this was a measure of realpolitik that was designed to make gains for Germany in bypassing the Versailles diktat, and was a formative move in what became a pro-Soviet orientation among much of the German Nationalist Right, especially with the rise of Stalin, a course that Spengler had himself suggested the possibility of: an Eastern orientation for Germany.[8] As for the Treaty of Rapallo, Trotsky was so aggravated by what he saw as concessions to Germany that he resigned as commissar for foreign affairs, rather than continue with negotiations with “German imperialists.”

The Jews of anti-Semitic stereotype were conspicuous. They were guilty of playing into the hands of uncompromising anti-Semites, which also suited the agenda of the then-insignificant Zionist movement in Germany. Indeed, from the birth of the Zionist movement, there has always been a symbiosis between anti-Semitism and Zionism to the point where Zionist agencies have provided the mainstay for neo-Nazi groups.[9] As will be seen here, briefly, the same symbiosis existed between the National Socialist party and the Zionists in Germany while both repudiated the German nationalists of Jewish descent. Until then, Zionism had received such opposition from Jews in Germany that Herzl’s original plans to hold the First Zionist Congress in Munich had to be changed to Basel.[10]

Weimar Jewish Influences

What then were the grievances of Germans against Jewish influences on the German political and cultural body? While the “philo-Semites” mentioned by Rathenau insisted then, as now, that Jews are eternally guiltless, the anti-Semitic movement that had been building in Germany, and was marked by a cultural basis that was most famously articulated by Richard Wagner,[11] objected to the Jewish over-representation in movements that were subversive to traditional morality, which also included the economic realm.[12 ] Weimar seemed to be the regime of the Jews.

A publication of the German League of Anti-Communist Associations, which appears to have been a National Socialist organization, is instructive as to the period. According to this, Jewish doctors were in the forefront of campaigns and legal defenses in favour of abortion, heralded by the abortion case of two Jewish doctors, Friedrich Wolf and Kienle-Jakubowitz, which was defended by a support committee including many Jews, including Dr Magnus Hirschfeld, founder of the Institute for Sexual Science, and therefore one of the pioneers of sexology.[13 ] Much of what was deemed indecent then, behind the façade of “science”, was also linked with Communist groups. Jews were prominent in all manner of Leftist parties,[14] and in the press, where they ridiculed the war veterans and any notion of patriotism.[15 ]

Nationalist German Jews

Max Naumann, chairman of the Verband Nationaldeutscher Juden (League of Nationalist German Jews), said of the Jewish influence in the press in 1926:[16]

“Anyone who is condemned to read every day a number of Jewish papers and periodicals, written by Jews for Jews, must on occasion feel an increased distaste, amounting to physical nausea, for this incredible amount of self-complacency, of slimy stuff about “honour”, and exaggeration of the duty to “combat anti-Semitism” which is understood in these circles in the sense that, at the slightest reference, the sword should be drawn if any Jew whatever is meant.”

Disingenuously, the German League of Anti-Communist Associations, quoting Dr Naumann, states of his League of Nationalist German Jews that “unfortunately this association did not succeed in acquiring any influence.” They then state, “It has not occurred at all to the majority of the Jews to adapt themselves to the forms of their German hosts…”[17]

Most German Jews were acculturated. What soon transpired is that the National Socialists were as avid as the hitherto inconsequential Zionists in Germany that German Jews should not become “good Germans.” Dr Naumann’s association of German Jewish nationalists was banned while the Zionist agencies in Germany were not only permitted to continue operating but enjoyed close relations with the new regime.

Naumann, a lawyer, had served as a captain in the Bavarian Reserve during World War I,[18] and was awarded the Iron Cross First and Second Class. The League of Nationalist German Jews, Verband Nationaldeutscher Juden (VNJ) was founded in 1921.

Naumann and his followers held that the Ostjuden immigrants were responsible for anti-Semitism. It was a widely held opinion. Furthermore, he stated that when the authorities did not act against such Jewish agitators and subversives, loyal German Jews were duty-bound to do so, in their interests and in German interests, which were one.

In 1920 Naumann and three other colleagues called on Ludwig Holländer, head of the primary German-Jewish organization, Centralverein, of which Naumann was a member, to express concern that the organization encouraged Jews to make political decisions based on Jewish rather than German interests. Naumann was a member of the right-of-center German People’s Party, and considered the Centralverein to be favoring other parties. It is notable that the Centralverein, like Naumann, was opposed to Zionism, and Holländer appealed to these common sentiments, however an invitation from Holländer for Naumann to write an article on his concerns fell through, as the article was regarded as too partisan in favor of the German People’s Party.[19]

Naumann regarded this rebuff as proof that the Centralverein supported the Democratic Party, and he began to oppose the organization for what he considered its party-political partisanship. An article written by Naumann for the People’s Party Rhineland newspaper, Kőlnische Zeitung, entitled “Concerning German Nationalist Jews” and reprinted as a pamphlet late in 1920, laid out Naumann’s doctrine. Here Naumann explained three types of German Jews: (1) The Zionists, whose proselytising among the youth demoralised the German-Jewish community and whose international connections seemed to justify claims of an international Jewish conspiracy; (2) The great majority of German nationalist Jews whose standpoint in politics was always German and never Jewish; and (3) an amorphous group whose loyalties were divided between German and Jewish interests.[20]

Of the German nationalist Jews, the doctrine that Naumman claimed for them has its roots in the German romanticism of Fichte, Herder, et al, in defining a nation as a matter of common consciousness rather than common blood. In this respect the National Socialists were a nationalist departure from the roots of German nationalism, more akin to the racial theosophy that arose in Austria-Hungary prior to World War I, while Naumann’s concept of nationalism seems to have been more in accord with the German national tradition.

The third group, which Naumann referred to as the “in-betweeners” (Zwischenschichtler) he regarded as being the real support base of the Centralverein, and the outlook included a hypersensitivity to“anti-Semitism”, including justifiable criticism of Jews.[21] The reaction of the Centralverein was dismissive and they claimed also to represent “German nationalist Jews.” Naumann responded that the Centralverein after twenty-seven years had been a failure both in negating the causes anti-Semitism and in forming a German identity among Jews. They had failed to respond to the challenge of the influx of Ostjuden, whom Naumann described as “the dangerous guest.”[22]

In response to the failure of Naumann and the Centralverein to reach agreement, Naumann and eighty-eight others founded the League of German Nationalist Jews, Verband nationaldeutscher Juden (VNJ) on March 20, 1921.[23] The League was vehemently opposed to Marxists and other subversive, anti-patriotic and pacifistic tendencies among Jews, to Zionism and to extending support to the Ostjuden, whose presence fostered anti-Semitism. To the VNJ, the Eastern Jews gravitated to communism and Zionism and other organizations and doctrines that “stand in opposition to everything German.” These foreign Jews were also involved in speculative capitalism. [24] Their actions had brought reaction against all Jews in Germany, and it was the duty of German nationalist Jews to fight these interlopers when the police would not or could not.[25]

The German Nationalist Jews actively opposed Zionist propaganda, and organized a boycott of a film on Palestine in 1924. In Breslau they persuaded the owner of the movie house to cancel the second screening of the film, stating that the money it raised was destined for an English-held land, and was therefore unpatriotic. In 1926 the “Naumannites”, as they were called, sponsored a lecture tour by an ex-Zionist, Robert Peiper, on the theme “The Truth about Palestine.”[26] Naumann urged Zionists in Germany to forswear German citizenship, and declare themselves a “national minority,” as the claims of “anti-Semites” that Germany was being taken over by Jews would seem justified, and there might come a time when they would have that status forced upon them under less favorable circumstances.[27]

Naumann advocated that Jews support patriotic parties regardless of the anti-Semitism of those parties, and that the example of Jewish German patriotism was the best way of combating anti-Semitism: i.e. by countering the source within the Jews themselves, rather than defending Jews regardless of their actions. As seen previously, it is a view that seems akin to that advocated by Walther Rathenau. Therefore the VNJ, without endorsing any party, prompted Jews to vote according to German interests.[28]

In 1925 the youth wing of the League’s Munich branch came to the defense of General Ludendorff, implicated as a leader of the Munich putsch with Hitler, when the General had been criticized by the Centralverein, although the League leadership was not supportive of Ludendorff.[29] The League also combated “anti-Semitism” within the German People’s Party, but the crucial difference between these German Nationalist Jews and other Jewish organizations was that it recognized that Jews were not invariably guiltless of the charges levelled against them for disloyalty and subversion, and advocated working with these “anti-Semitic” parties, rather than confronting them.

Although at least two League members remained members of the Centralverein committee, the Centralverein and the VNJ were increasingly antagonistic towards each other, and “the liberal Jewish press in Germany was virtually unanimous in concluding that the Naumannites were ‘Jewish anti-Semites’”, states Niewyk, who remarks that the Jewish leadership were fearful of alienating the socialist movement. The Centalverein went on the offensive in opposing Naumann, who responded by libel suits against leaders of the organization.[30] The Centalverein was largely successful in preventing Naumann from advocating among German Jews. In 1930 the VNJ’s “German List” of candidates for the Berlin Jewish community’s representative assembly drew less than 2% of the vote. The circulation of the VNJ’s newspaper never exceeded 6,000 according to Niewyk.[31]

From 1932 the Naumannites gained renewed attention by focusing on the anti-Semitism of the National Socialist party, and the illegitimacy of the National Socialists as German patriots. The Naumannites saw an “idealistic essence” in National Socialism that was obscured by racism, and considered that Hitler would outgrow Judaeophobia. The Naumannites advocated that Jews should join non-Nazi nationalist organizations, which could nonetheless aid the Nazis, and perhaps diminish the influence of the more vitriolic of the anti-Semites. Naumann supported the “German socialism” that had been a feature of the Right, and not only among the National Socialists. Oswald Spengler for example had advocated a type of “ethical socialism” that would place the German state above class and other factional divisions.[32] Like Spengler, Naumann opposed German Social Democracy and Marxism, and was concerned at the number of Jews involved with the Left.[33]

Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-13167 / CC-BY-SA [CC-BY-SA-3.0-de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons

It is here relevant to note that in the 1932 presidential election the National People’s Party candidate, standing against Hitler, was Lieutenant Colonel Theodor Duesterberg, second in command of the monarchist-nationalist veterans’ organization, the Stahlhelm. Duesterberg was attacked by Goebbels’s newspaper Der Angriff because of his Jewish background. Officers of the Stahlhelm responded that “if Duesterberg is of Jewish origin, the absurdity of racial discrimination is proved inasmuch as Duesterberg was an outstanding officer on the war front and was delegated by true Germans as their candidate for president of the German Republic.”[35]

While Duesterberg claims he was unaware of his Jewish background it is the supportive reaction of his fellow veterans that is of interest, while Ludendorff, like the Nazis, denounced him, which resulted in his withdrawal from the second run-off of the presidential race. Duesterberg resigned from his position in the Stahlhelm following his defeat in the presidential elections, and the revelations as to his Jewish background, but his resignation was rejected. The Jewish Telegraphic Agency reported at the time:[36]

“Leaders of the Stahlhelm have labelled as absurd that racial descent should be regarded as in any way inimical to Duesterberg’s continuation in office and have not hesitated to denounce the Nazi campaign against him on this score as deliberate provocation. For this reason, the praesidium of the Stahlhelm did not accept the proffered resignation of Duesterberg and prevailed upon him to remain in office. Leaders of the Steel Helmet are not desirous of acknowledging that the Nazi campaign against Duesterberg has had any repercussions in the Steel Helmet camp. This is said to explain the silence which is being maintained on what transpired at the meeting of the praesidium.”

The Stahlhelm further stated of Duesterberg:[38]

“We are aware that Duesterberg’s father in 1813 volunteered as a soldier for the liberation of Germany and was awarded the Iron Cross. Duesterberg himself was wounded in the Expedition to China.[37] Subsequently he fought in the World War in the most dangerous places.”

Although being offered, and declining, a position in Hitler’s first Cabinet, Duesterberg was arrested during the Night of the Long Knives in 1934 and interned at Dachau, but was released, dying in 1950.

German Jewish Nationalist Youth Organizations

In 1932 a three-way split between Leftist and Rightist factions in the German Jewish youth organization Kameraden resulted in the formation of the Black Squad (Schwarzes Fähnlein) by 400 conservative-nationalist members. The Black Squad sought to revive the medieval Teutonic martial ethos.

In 1933 a young Jewish theologian, Dr. Hans-Joachim Schoeps, established a 150-member “German Vanguard – German Jewish Followers” also devoted to martial values. In April 1933 the Black Squad and the German Vanguard aligned with the VNJ and the National League of Jewish Frontline Veterans into an Action Committee of Jewish Germans that hoped to negotiate with the National Socialist regime on a new dispensation for German Jews. This organization, like the VNJ and the other German Jewish nationalist groups, was outlawed by the National Socialist regime in 1935.[39 ]

Schoeps adhered to the German Conservative Revolution movement that emerged in the aftermath of World War I. Among the influences on Schoeps from this milieu were Stefan George, Ernst Jünger, Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, Ernst Niekisch, Carl Schmitt, Oswald Spengler, Otto Strasser, and others. Schoeps never repudiated his Rightist sentiments in the post-1945 era, writing in 1960 that Spengler’s “Prussian socialism” remained valid.[40]

Schoeps sought an accord between patriotic German Jews and National Socialism, writing in his newspaper The Vanguard that National Socialism can renew Germany, and that German Jews should be brought under a new organization representing them as German patriots.[41]

German Jewish Nationalist War Veterans

The German Jewish World War veterans had their own association, Reichsbund jüdischer Frontsoldaten (RjF), that was, like the League of German Nationalist Jews, opposed to Zionism, Marxism and all other manifestations of subversion. From 1930 until 1934 Ludwig Freund, general secretary of the RjF, “gave lectures all over Germany with titles such as ‘Community of the Frontlines – Community of the Volk’ to audiences of non-Jewish veterans.” They also opposed the influx of Ostjuden.[42]

RjF was founded in 1919 to counter claims that German Jews had shirked their military duty during the World War. Despite its repudiation of this basic National Socialist allegation, the RjF, like the Naumannites, hoped for an accommodation with the Hitler regime for German Jews. Generally, fascism had arisen throughout Europe in the aftermath of the World War primarily from war veterans. It should be no surprise that fascism also emerged from Jewish war veterans, and that Jewish veterans also joined fascist movements, especially in Italy where by the mid-1930s one-third of the adult Jewish population were members of the National Fascist Party, and 230 Jews participated in the March on Rome.[43] Ettore Ovazza, scion of a wealthy family who, with his two brothers and fifty-year-old father had enlisted with the Italian army to fight the world war, founded a “stridently pro-fascist journal” and physically led an attack on Zionist Jews.[44]

While there is nothing inherent in fascist ideology that prohibits Jewish support, the anti-Semitic element of German National Socialism was a common feature of German romanticism, which as noted, had reached its most cogent expression from Richard Wagner. The Hitlerites were heirs to that legacy, as well as to pre-war anti-Semitic and racial doctrines in Central Europe.[45]

The RjF, states Caplan in his study of the subject, “claimed to be models of the tough, self-confident, and disciplined ethos they believed to be necessary for the survival of German Jewry. As the first ever German-Jewish military elite, they sought to transmit their military masculinity to the rest of the German-Jewish community through youth and sports programs, the commemoration of the Jewish war dead, and the promotion of Jewish cultivation of German soil.”[46] Unlike the Naumannites and other German-Jewish nationalists, the RjF cannot be dismissed as marginal. By the mid-1920s the RjF had 35,000 members and was the third-largest organization of German Jews.[47 ]

Caplan writes of the generically fascist character of the Jewish war veterans (as with other war veterans in Germany who joined the Hitlerites, the Stahlhelm and the Freikorps), that they “offered a popular platform for the battle against the pitfalls of big-city life at a time of rapid social transformation. Falling birth rates, alcoholism, and the spread of nervous disorders had already been diagnosed by the turn of the century as indicators of social and cultural degeneration. The German military defeat and its revolutionary aftermath exacerbated this sense of crisis and added to the list of perceived symptoms.”[48]

Relations with the Third Reich

As indicated by the vehemence of the National Socialist campaign against the esteemed head of the Stahlhelm, Lieutenant Colonel Duesterberg, there was not much room for optimism that the regime would accommodate even the most loyal of German Jews, other than that Germans of partial Jewish descent were categorized and some categories were granted a tolerable status under the 1935 Reich Citizenship Law.

Caplan states that although the Hitlerites remained an enemy, “nevertheless, the leaders of the RjF also subscribed to a political ideology that incorporated all of the elements generally associated with fascism – militarism, extreme nationalism, anti-bolshevism, and middle-class desires for a strong state that would transcend divisive parliamentary structures.”[49] That German Jewry ended up choosing Zionism rests squarely on the shoulders of the National Socialist regime, which favored Zionism as a doctrine that likewise opposed assimilation of Jews into the national community.

With the accession to Office of the National Socialists, the RjF believed that it was essential that they assume leadership of German Jewry. Despite their opposition to the Nazis from the start due to the Nazi propaganda that sought to deny the Jewish role in the World War, the values the RjF espoused for German Jews, and especially for the young, were in accord with the doctrines the National Socialists expounded to “Aryan” Germans. As long “as the state seemed to honor the link between military service and German citizenship – and even longer – the RjF sought to cooperate with the Hitler regime in the construction of a viable Jewish community in the Third Reich. […] the ideology, language, and tactics of the RjF reflected a fascist, anti-Zionist agenda that transcended rhetorical pandering of the oppressed to the oppressor.”[50]

The RjF now proclaimed itself specifically against Zionism, dropping its hitherto neutral stance. The RjF become more active than ever in the first years of the regime, and its popularity increased at the expense of the oldest and largest of the Jewish organizations, the Centralverein. Jews were increasingly antagonistic towards the Centralverein’s “passivity in response to Zionism”[51] in a Jewish population where Zionism had never taken root. Liberalism was diminishing drastically among the German Jews also in line with the decline of Liberalism in Germany generally in the aftermath of the world war. With the demise of Liberal hegemony among German Jews, the choice was between Zionism and the fascism of the RjF.

While Ludwig Freund left Germany in 1934, Dr Leo Loewenstein, chairman of the RjF, a scientist by profession, who had served as a captain in the Bavarian Army Reserve, attempted from 1933 to 1935 to “persuade Hitler by mail to allow patriotic Jews, and the young generation in particular, to be absorbed into the German Volksgemeinschaft,” to allow Jewish youth to participate with German youth in athletic contests and to allow Jews to serve in the German armed forces. [52] While there was no reply from Hitler, Loewenstein did succeed in April 1933, by appealing to President von Hindenburg, “in having Jewish civil servants with frontline service during wartime exempted from losing their jobs.” However the exemption was revoked with Hindenburg’s death later that year.[53]

When world Jewish organizations declared a boycott of German goods in 1934,[54] and established the World Jewish Economic Federation to deprive Germany of foreign capital, the RjF reacted swiftly, condemning the actions of Jewish leaders far-removed from Germany, writing to the US Embassy in Berlin denying, “as German patriots,” allegations that Jews in Germany were being subjected to “cruelties.” While acknowledging that excesses had occurred that are unavoidable in any kind of revolution, they commented that where able, the authorities have sought to prevent these. The RjF also condemned the “irresponsible agitations on the part of the so-called Jewish intellectuals living abroad.” These had “never considered themselves German nationals,” but had abandoned those of their own “faith” at a “critical time” while claiming to be their champions.[55] The same day the RjF issued a worldwide address to frontline veterans, stating that the propaganda against Germany was politically and economically motivated. They pointed out that the Jewish writers used as propagandists had hitherto been the same propagandists who had “scoffed at us veterans in earlier years,” and called on “honourable soldiers” to repudiate the “unchivalrous and degrading treatment meted out to Germany…”[56]

The choice of Germany’s Jews between German nationalism and Zionism was decided by the regime for the Jews, in favor of Zionism. While approximately 600 newspapers were officially banned by the National Socialist regime during 1933, and others were pressured out of existence, Jüdische Rundschau, the weekly newspaper of the Zionist Federation of Germany (ZVfD) was permitted to flourish, and by the end of 1933 had a circulation of 38,000, four to five times more than in 1932. Jüdische Rundschau was even exempted from newsprint restrictions until 1937. The Zionist newspaper was not subjected to the same censorship as other German newspapers. They were the only newspaper in the Third Reich permitted to advocate an independent political doctrine. In 1935 the Zionist youth corps was the only non-Nazi body permitted to wear uniforms. With the 1935 Nuremberg Laws, German Jews were prohibited from raising the German flag, but could raise the Zionist flag.[57] German-Jewish nationalists were not wanted in the Reich, including the Jewish war veterans’ organization, whose German nationalist doctrine could have won over at least a significant proportion of German Jews who had rejected Liberalism and had not been inclined towards Zionism.

Both the German Vanguard and the League of German Nationalist Jews were dissolved in late 1935, while the RjF endured until the end of 1938.

Schoeps’s prior contacts with the anti-Hitler National Socialist Otto Strasser, and the “National Bolshevik” Ernst Niekisch made him suspect and he emigrated to Sweden in 1938. After the war he established a celebrated career as a theological scholar. He also remained an active monarchist, and as a leader of the National Association for the Monarchy (Volksbund für die Monarchie), called for the restoration of the State of Prussia in 1951, and was involved in forming subsequent conservative movements and periodicals. He died in 1980 in Germany.

Freund, of the RjF, emigrated to the USA in 1934 and returned to Germany in 1961. Far from having repudiated his Germanness like the many Jews who turned to Zionism, he was one of the first three men to be awarded the Adenauer Prize in 1961 by the German Foundation for his work in the “revival of a healthy national feeling on the basis of necessary self-respect” and for the “protection of the rights of the German Volk, in spite of the wrongs done him in his own Fatherland,”[58] such nationalistic sentiments and awards being condemned by Der Spiegel.

Conclusion

German Jews had rejected liberalism for the same reasons as other Germans had turned to the Right, hoping for a national renewal of the Fatherland. Zionists had not made significant inroads, and while German-Jewish nationalist organizations such as those of Naumann remained small, they maintained a challenge to the mainstream Jewish organizations. The RjF was not marginal, however, and was gaining support for its form of fascism that sought to fully identify Jews with Germany. They were undertaking in particular a program among the Jewish youth of the type that had been sought by Rathenau, to recreate a Jewish youth that was robust, martial and patriotic. The German Zionists undertook a similar program in the interests of creating vigorous youth pioneers for Palestine.

If the RjF had been permitted to proselytize among German Jews they would have captured the majority of that community for Germany, despite the anti-Semitism that existed to varying degrees among the National Socialists. Jews had for centuries undertaken a process of acculturation reflected in the many Jews who fought for Germany during the world war. Unfortunately, the most conspicuous Jews, promoted no less by the anti-Semitic press than by their own followers, were the likes of Rosa Luxemburg, Willi Münzenberg, the wealthy publisher of the Communist press Karl Radek, Kurt Eisner, et al., until Communism became synonymous in Germany,[59] as in much of the rest of the world, with Jews. However, only 4% voted for the Communist Party, and 28% for the Social Democrats. Most were moderate liberal-democrats.[60] There was also a widespread, vigorous dislike, one might say even hatred, for the “Eastern Jews” that were coming into Germany, especially after the war, whom Rathenau condemned with such vehemence. The “liberal” Jews were just as offended by the manners of the Ostjuden as anyone else.

The Jewish German nationalists sought acculturation, the continuation of a process that had been taking place for centuries. In the Zionists, the National Socialists had allies as opposed to assimilation as themselves. While the Zionists continued collaborating with the Third Reich even during the war, German-Jewish nationalists were suppressed, although a significant number of Mischlinge maintained their patriotism and were able to serve Germany, including Hitler’s original bodyguard and SS commander Emile Maurice, first commander of what became the SS who, over Himmler’s objections and due to Hitler’s insistence, remained an honored officer of the SS, as did his brothers.[61]

The National Socialists maintained a type of Manichean outlook that saw the Aryan in mortal combat with the Jew as a conflict between God and the Devil, a synthesis of biology and theology that had since the late 19th century portrayed the Jews as less than human, or bestial spawn, expressed in the New Templar theosophy of Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels.

Where most German Jews saw the Ostjuden as a danger to Germany, or at best an embarrassment to themselves, the National Socialists did not distinguish between them. While only a minority of Jews supported the Left, the National Socialists focused on the conspicuous Jewish presence in the Communist movement, and in other anti-German movements. Most particularly, the Third Reich did not accord status to Jewish war veterans, and the regime chose Zionism over German-Jewish nationalism.

Notes:

| [1] | Bryan Mark Rigg, The Untold Story of Nazi Racial Laws and Men of Jewish Descent in the German Military (University Press of Kansas, 2002). |

| [2] | Raul Hilberg, Documents of Destruction (London: W H Allen, 1972), pp. 18-24. |

| [3] | Amos Elon, The Pity of It All: A History of the Jews in Germany 1743-1933 (Allen Lane, 2003). |

| [4] | “Die Gangbarsten Antisemitischen Lügen (Einiges zur Widerlegung),” Abwehr-Blätter, XLII (October 1932), cited by Hilberg, op. cit., p. 11. Online: http://periodika.digitale-sammlungen.de/abwehr/Blatt_bsb00000940,00203.html |

| [5] | Walther Rathenau, “Hear, O Israel!”, Zukunft, No, 18, March 16, 1897; in Paul R Mendes-Flohr and Jehuda Reinharz (editors), The Jew in the Modern World: A Documentary History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), p. 232. |

| [6] | “The Ghetto Comes to Germany: Ostjuden as Welfare Cause,” East European Jews in the German-Jewish Imagination, Committee on Jewish Studies, University of Chicago Library, http://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/webexhibits/RosenbergerEastAndWest/TheGhettoComesToGermany.html |

| [7] | Spengler to Rathenau, May 11, 1918; Rathenau to Spengler, May 15, 1918, in Spengler Letters 1913-1936 (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1966), pp. 62-63. |

| [8] | Oswald Spengler, “The Two Faces of Russia and Germany’s Eastern Problems,” Politische Schriften, Munich, February 14, 1922, cited in: K R Bolton, Thoughts and Perspectives Volume Ten: Spengler, Troy Southgate, editor (London: Black Front Press, 2012), p. 124. |

| [9] | K R Bolton, “The Symbiosis between Anti-Semitism and Zionism,” Foreign Policy Journal, November 1, 2010, http://www.foreignpolicyjournal.com/2010/11/01/the-symbiosis-between-anti-semitism-zionism/ |

| [10] | “The First Zionist Congress and the Basel Program,” Jewish Virtual Library, http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org |

| [11] | Richard Wagner, Judaism in Music, 1850, http://users.belgacom.net/wagnerlibrary/prose/wagjuda.htm |

| [12] | Werner Sombart (1911), The Jews and Modern Capitalism (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Books, 1982). |

| [13] | Jewish Domination of Weimar Germany 1919-1932 (German League of Anti-Communist Associations (Berlin: Eckart-Verlag, 1933), p. 12. |

| [14] | Ibid., pp. 21-29. |

| [15] | Ibid., pp. 15-16. |

| [16] | Max Naumann, 1926, cited in Jewish Domination of Weimar Germany, ibid., p. 15. |

| [17] | Ibid. |

| [18] | Donald L Niewyk, The Jews in Weimar Germany (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2001), p. 165. |

| [19] | Ibid. |

| [20] | Ibid., p. 166. |

| [21] | Ibid., p. 167. |

| [22] | Max Naumann, Vom nationaldeutschen Juden (1920), cited by Niewyk, ibid. |

| [23] | Niewykj, ibid. |

| [24] | Max Naumann, “Dennoch!”, 1922, cited by Niewyk, ibid., p. 170. |

| [25] | Max Naumann, 1923, cited by Niewyk, ibid. |

| [26] | Niewyk, ibid., p. 171. |

| [27] | Max Naumann, Von Zionisten und Jüdisch-nationalen (Berlin, 1921), pp. 26-48; cited by Niewyk, ibid. |

| [28] | Ibid., p. 172. |

| [29] | Ibid. |

| [30] | Ibid., p. 173. |

| [31] | Ibid., p. 175. |

| [32] | Oswald Spengler, Prussianism and Socialism, 1920, http://archive.org/details/PrussianismAndSocialism |

| [33] | Niewyk, op. cit., p. 175. |

| [34] | Ibid., p. 176. |

| [35] | “Duesterberg, Stahlhelm Leader, Candidate for President, Says He Is of Jewish Origin,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, September 7, 1932. |

| [36] | “Confirm Proffer of Duesterberg Resignation; Stahlhelm Prevails on Him to Remain,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, September 9, 1932. |

| [37] | Boxer Rebellion. |

| [38] | “Stahlhelm Headquarters Reveal Duesterberg Became Ill when Jewish Origin Revealed,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, September 14, 1932. (Duesterberg had a nervous breakdown as a result of the vitriolic Nazi campaign against him). |

| [39] | Niewyk, op. cit., p. 176. |

| [40] | Richard Faber, Deutschbewusstes Judentum und jüdischbewusstes Deutschtum – Der Historische und Politische Theologe Hans-Joachim Schoeps (Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2008), 103 ff. |

| [41] | Hans-Joachim Schoeps: Bereit für Deutschland: Der Patriotismus deutscher Juden und der Nationalsozialismus (Berlin: Verlag Haude & Spener 1970), pp. 106, 114. |

| [42] | Gregory A Caplan, “Acknowledging German-Jewish Fascism,” in Amazing Differences: Young Americans Experience Germany and Germans, Alexander Von Humboldt-Stiftung/Foundation, Bonn, 2001, p. 3, http://www.humboldt-foundation.de/pls/web/docs/F30142/reflections_99.pdf |

| [43] | Roger Eatwell, Fascism: A History (London: Vintage, 1996), p. 66. |

| [44] | Ibid. |

| [45] | Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, The Occult Roots of Nazism: The Ariosophists of Austria and Germany 1890-1935 (Northamptonshire: The Aquarian Press, 1985), pp. 33-216. |

| [46] | Caplan, op. cit. p. 4. |

| [47] | Ibid. |

| [48] | Ibid., pp. 7-8. |

| [49] | Ibid., p. 8. |

| [50] | Ibid., p. 8. |

| [51] | Ibid., p. 9. |

| [52] | W Angress, “The German Jews, 1933 – 1939,” in: M Marrus, (ed.), The Nazi Holocaust, (Westport & London, 1989), Vol. 2, pp. 484 – 497. |

| [53] | Ibid. |

| [54] | “Judea Declares War on Germany,” Daily Express, March 23, 1934. |

| [55] | Quoted by Udo Walendy, The Transfer Agreement and the Boycott Fever 1933, Historical Facts No. 26, 1987, p. 5. |

| [56] | Walendy, ibid. |

| [57] | Edwin Black, The Transfer Agreement – the Untold Story of the Secret Pact between the Third Reich and Jewish Palestine (New York: 1984), p. 175. |

| [58] | “Wahrung der Rechte,” Der Spiegel, No. 11, pp. 22-24, quoted by Caplan, op. cit., p. 4. |

| [59] | “The Jews as the Apostles of Communism”, in: Jewish Domination of Weimer Germany, op, cit., pp. 21-29. |

| [60] | Lenni Brenner, Zionism in the Age of the Dictators (Westport, Connecticut: Lawrence Hill, 1983), p. 27. |

| [61] | “Maurice, Emil,” http://ww2gravestone.com/general/maurice-emil |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 5(3) (2013)

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a