The Thin Internal Walls of Krematorium I at Auschwitz

A Small Detail with Far-reaching Consequences

Abstract

The room inside the old crematorium of the Auschwitz Main Camp that was a morgue according to original war-time plans is said to have been used as a homicidal gas chamber between late 1941/early 1942 and the first half of 1943. It would seem that operating a homicidal gas chamber requires the installation of gas-tight, panic-proof doors to keep both the poisonous fumes and the victims safely inside. While there is no evidence in the extant documentation pointing to the existence of any such doors, orthodox historiography points to witness testimony indicating that such doors were in fact in place. A closer scrutiny of war-time blueprints reveals that the walls of this morgue which must have supported these doors were extremely thin, hence unable to support the installation of massive steel doors.

The Impetus for this Paper

On November 20, 2019, I received the following email:

“Hello, my name is Federico Bussone, I’m from Italy. I think I have discovered an important weak point in the mainstream official story of the Auschwitz Main Camp crematorium. As far as I know, this weak point has never been highlighted by any revisionist, and so I would like to share with you my ‘discovery.’

We have to look at the original blueprint of the Crematorium I of April 10 1942 (but also the one from November 30 1940).

In both these plans, the wall of the left (short) side of the alleged gas chamber, that is, the wall with the entrance door, is REALLY THIN, it probably measures no more than 15 centimetres. As an architect, I understand well that such a partition could only have served as a dividing wall. It could have never withstand [sic] the stresses produced by the opening and closing of a heavy steel door. Let alone the blows and the pressure towards the outside exerted by the panicked prisoners.

I would like to emphasize that this type of wall, built of small solid bricks bound by mortar, became quite resistant only when built in a double row. In a single row, as it is in our case, it can be easily demolished with a little sledgehammer by a single worker, for example during house renovation.

It seems to me that this important fact has not been grasped so far. For example, the 3D models by Eric Hunt have the same (greater) thickness for all walls. The same for other drawings I have found in revisionist publications etc.

I hope this mail will be helpful!

Best regards.

Federico”

The Orthodox Narrative

After the former Polish military barracks south of the Polish city of Oswiecim had been converted into a concentration camp by German authorities following the Polish defeat in September 1939, the old munitions bunker on the grounds of that camp was converted into a crematorium for the incineration of the remains of deceased or executed inmates. In war-time and post-war literature, this building is alternately referred to as either the old crematorium or Crematorium I. The morgue of this facility is said to have been converted into a homicidal gas chamber subsequent to an initial test gassing conducted in the camp’s gaol in September of 1941.[1] This was asserted already two months prior to the end of World War Two by a combined Polish-Soviet investigative commission, which stated the following about this in its report:[2]

“In early 1941, a crematorium, designated as Crematorium #1, was started up in the Auschwitz camp. […] Next to this crematorium there was a gas chamber, which had, at either end, gas-tight doors with peep-holes and in the ceiling four openings with hermetic closures through which the ‘Ziklon’ [sic] for the killing of the persons was thrown. Crematorium I operated until March 1943 and existed in that form for two years.”

In preparation for the 1947 Polish show trial against former Auschwitz camp commandant Rudolf Höss, Polish engineer Dr. Roman Dawidowski compiled an expert report on evidence supporting homicidal gassing claims at Auschwitz, where we read on this topic:[3]

“One now [in late 1941[4]] began to poison people regularly with Zyklon B and to use for that purpose the Leichenhalle (morgue) of Crematorium I […]. This chamber […] on both sides had a gas-tight door.”

Jan Sehn, the Polish judge who led the investigation leading up to the Polish post-war show trials against former members of the German Auschwitz camp staff, wrote the following about this in his 1960 book on Auschwitz:[5]

“The mortuary (Leichenkeller)[6] of the first Oswiecim crematorium […] was fitted with two gas-proof doors.”

Claims about gas-tight doors in that morgue originate from witness testimony. Among them is Stanisław Jankowski, who stated regarding the doors in that room in a deposition October 3, 1980:[7]

“The two thick wooden doors of the room, one in the side wall, the other in the end wall, had been made gas-tight.”

The post-war autobiography by Rudolf Höss, written while in Polish custody awaiting his execution, contains little information about the doors of this alleged gas chamber, only that they must have been very sturdy, because:[8]

“When the powder [sic; Zyklon B] was thrown in [to the gas chamber], there were cries of ‘Gas!’, then a great bellowing, and the trapped prisoners [Russian PoWs to be gassed] hurled themselves against both the doors. But the doors held.”

Höss moreover speaks repeatedly of the doors being “screwed” shut,[9] which points to a door with massive steel fixtures not found on usual doors.

In his post-war declaration writing in the summer of 1945, former SS man Pery Broad was a little more specific about the doors of this claimed homicidal gas chamber, making it clear that this was a heavy, gas-tight, panic-proof door:[10]

“Suddenly the door was closed. It had been made tight with rubber and secured with iron fittings. Those inside heard the heavy bolts being secured. They were screwed to with screws, making the door air-tight. A deadly, paralysing terror spread among the victims. They started to beat upon the door, in helpless rage and despair they hammered with their fists upon it.”

While interrogated in preparation of the first Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial, defendant Hans Stark made the following statements in his deposition about the doors of that room:[11]

“As early as the autumn of 1941 gassings were carried out in a room of the small crematorium, the room having been fitted for that purpose. It could take in some 200–250 people, was higher than a normal living room, had no windows, and only one door that had been made [gas] tight and had a lock like the door of an air-raid shelter.”

The Current Material Situation

In the fall of 1944, the section of the old crematorium that contained the morgue, the washroom and the laying-out/dissecting room was converted into an air-raid shelter for the SS.[12] For this purpose, the former interior walls of that section as well as the walls separating it from the furnace room were changed – I will address this in more detail later – and probably also the doors, as documentation indicates that the shelter’s interior doors were of a “simple” nature,[13] hence neither gas-tight nor fragment-proof, as was initially foreseen, nor panic-proof, as would have been required for homicidal purposes.12

In 1947, the freshly established Polish Auschwitz-Museum authorities restructured the building, among other things by removing some of the former air-raid shelter’s internal walls. By so doing they tried to recreate the state as it was before the conversion of this facility to an air-raid shelter. During that process, a number of mistakes were made, among them the removal of a wall which did exist in the pre-shelter era, separating the alleged gas chamber from the adjacent washroom. Only one internal wall was left, which used to separate the washroom from the laying-out/dissecting room. To this very day, this wall has a “simple interior wall” as installed during the conversion to an air-raid shelter.

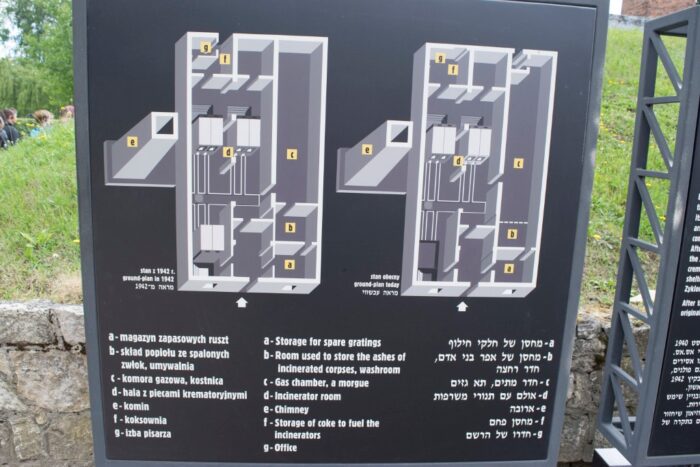

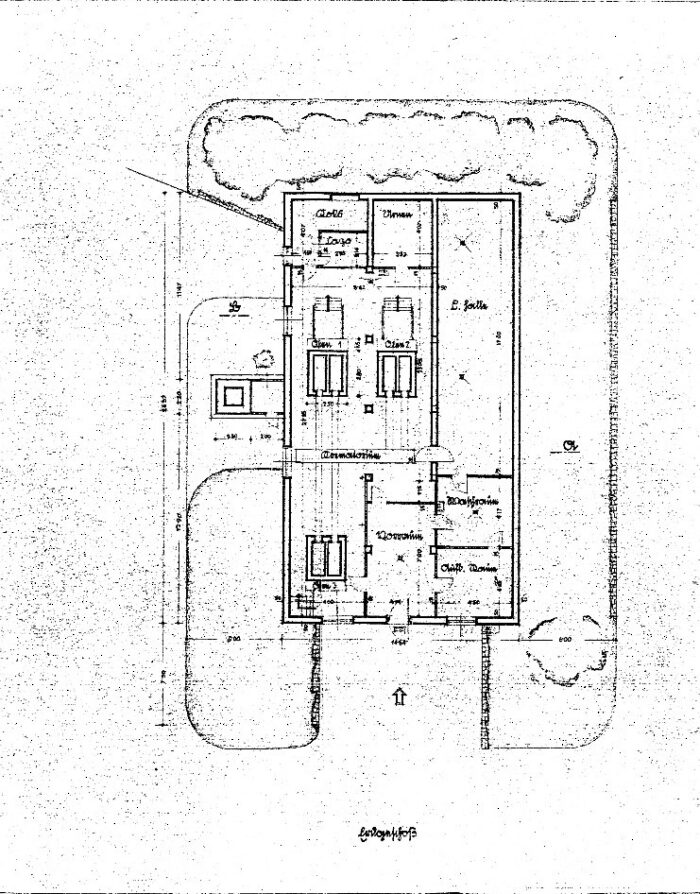

Only after the collapse of the Communist Eastern Bloc did the Polish Auschwitz authorities start to acknowledge the fact that the facility as presented to visitors today is not an accurate “reconstruction” of the former alleged gas chamber, although the tour guides kept misrepresenting it to visitors. A sign hinting at a few of the inaccuracies of this botched reconstruction was installed near that building only in the early 2000s, see Illustration 1. The wall originally separating the morgue (or “gas chamber”, marked “c” on the plans) from the washroom (marked “b” on the plans) is missing today.

The Revisionist Position

Starting from the assumption, caused by the Auschwitz Museum’s decade-long misrepresentation, that today’s state of the building is an accurate reconstruction of the situation during the war when homicidal gassings are said to have occurred, revisionists highlighted the fact that the extant doors (or the lack thereof) in the claimed gas chamber would never have allowed the claimed mass murder. For instance, Swedish eccentric revisionist Ditlieb Felderer wrote in 1980:[14]

“The doorposts [of the door separating the alleged gas chamber from the former laying-out/dissecting room] are made of wood, and the door itself is made of wood and glass. The handle and lock are so weak that they keep falling apart. The door opens inwards, into the ‘gas chamber.’ When we asked Mr. T. Szymanski, the (now retired) curator, how it was that the gassees did not just smash the window in this door and escape, he advised us that he had never investigated this door so he could not give us a definite answer!”

The famous 1988 Leuchter Report acknowledged that the current state of the building is not original, “since one wall had been removed,” and therefore did not make any statement about the door currently visible.[15] However, at the end of a 1994 article, revisionist Robert Faurisson, ghostwriter of the Leuchter Report, added two images comparing the massive steel door of a US execution gas chamber with the flimsy wooden door with window pane which has been visible in the old crematorium since the wall from the morgue to the washroom had been knocked down in 1947. The caption to the image showing that door reads:[16]

“One of the three doors of an alleged NS gas chamber for the execution of hundreds of persons at once with Zyklon B (hydrogen cyanide) (Krematorium I, Auschwitz, Poland, beginning of the 40’s).”

The same illustration with the same misleading caption can be found in the 2000 and 2003 English editions,[17] but has been removed in the 2019 edition. It is misleading, because it was well known by the time these books were published that this door was never part of a homicidal gas chamber, even if the Auschwitz tour guides were still claiming this in the 1990s and early 2000s, and some may still be doing it today.

In 2005, the English translation of Carlo Mattogno’s monograph on Krematorium I was published.[18] While it contains most of the witness testimony quoted earlier and goes into some detail about the various restructurings this building went through, it does not specifically address the question of the doors presumably installed in that building’s morgue while allegedly used for homicidal purposes.

The same year also saw the first English (and 2nd German) edition of my Lectures on the Holocaust, where I briefly addressed the issue of access doors to the morgue, albeit with a focus on the swing door between the morgue and the furnace room, shown on several war-time floor plans.[19] The same emphasis on that swing door, with much more detail, can be found in Eric Hunt’s introductory contribution to C. Mattogno’s 2016 book Curated Lies.[20] While this proves that the blueprints do not reflect any outfitting of the morgue for homicidal purposes, it can be argued that such secrecy was in fact intentional, meaning that the floor plans were simply not updated in this regard, in particular regarding the swing door, in order to conceal the criminal changes made.

Extant Documentation

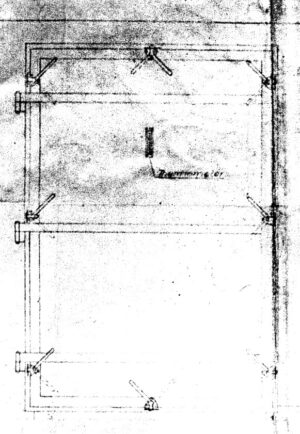

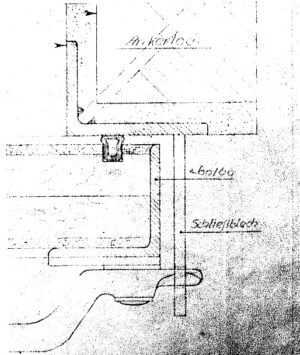

In a long 1998 article, German architect Willy Wallwey, writing under the pen names of Hans Jürgen Nowak and Werner Rademacher, summarized what the extant documentation accessible in various Moscow archives reveals about gas-tight doors offered to, delivered to and installed in the various buildings at Auschwitz.[21] Wallwey concluded that the Auschwitz camp authorities did indeed request cost estimates for sturdy, gas-tight, and probably also panic-proof steel doors, but they were never delivered. These doors even had so-called wedge locks used to close them in an air-tight fashion, a closing mechanism that could be called “screwing” the doors shut as described by witnesses, see Illustration 3.[22]

The two existing air-raid-shelter doors made for Krematorium I in 1944 during the building’s conversion to an air-raid shelter are made of wooden planks covered by thin sheet metal, see Illustration 4. Although these doors were probably built by the local inmate workshop, so far no documentation about them has been found. This proves that not everything that was constructed at the Auschwitz Camp left a trace in the documental record, or if it did, that it has survived. Hence, it is conceivable that sturdy gas-tight doors similar to those shown in Illustrations 2f. were in fact delivered to Auschwitz and were subsequently installed there without leaving a documental trace.

The Blueprints

While it cannot be ruled out that panic-proof, gas-tight steel doors were indeed delivered to Auschwitz and may have been installed elsewhere, it can be ruled out, based on war-time floor plans, that any such door could have been installed in the relevant door openings of the morgue of Krematorium I.

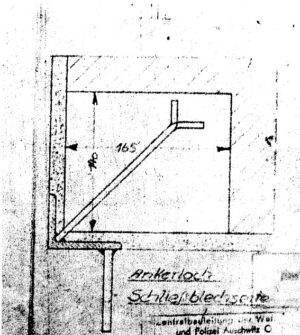

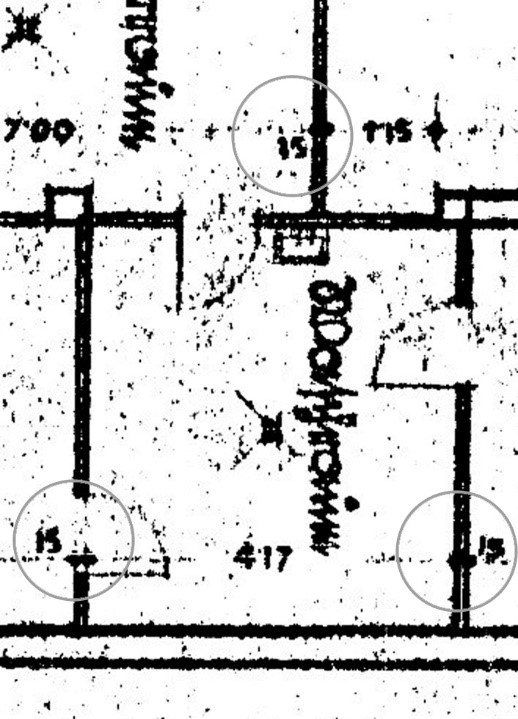

First, we need to be aware that the frame of a massive wooden or even a steel door designed to withstand a panicking crowd needs to be anchored firmly in the wall. Illustration 5 shows a hoop steel anchor with a so-called dovetail going some 14 cm (5.5 inches) into the wall.22 Needless to say, the wall itself had to be considerably thicker than 14 cm.

Turning to the war-time floor plans of this morgue, we see that the wall separating the morgue from the adjacent washroom and the wall separating it from the furnace room were both very thin: 15 cm, which is the width of a standard brick plus some plaster on both sides of it (see Illustration 6 and 7). Hence, these walls consisted only of one row of bricks set lengthwise. The wall separating the morgue from the furnace room consisted of two such walls with a gap of some 30 cm in between (for thermal insulation).

It is not possible to set a steel anchor into bricks. In such a case, bricks have to be removed, and then the anchor placed into a block of cement/concrete. However, since these walls consisted only of one row of bricks – unless they consisted only of a wooden framework of 2-by-5s plus some boards, in which case we need no longer discuss this issue – removing a brick to place an anchor embedded in cement in its stead would have left this chunk of cement held in place by nothing more than the bricks on top and at the bottom of it. Such a chunk would have become loose very quickly. Any forceful shaking of the door would have dislodged those anchors, bent the frame, and made the frame including the door fall out of the wall sooner or later.

In other words, the meager thickness of these walls proves that no sturdy, panic-proof door of any kind could have been installed in them.

The only option left for the traditionalists is to claim that these walls were reinforced to a much thicker width at the very moment the morgue is said to have been converted into a homicidal gas chamber, meaning in September 1941. Yet no evidence exists for this neither in the documental record nor in witness testimonies known to me.

As the late Dr. Robert Faurisson put it aptly:

“No doors, no destruction.”

Endnotes

| [1] | The currently accepted orthodox narrative of the so-called first gassing is succinctly summarized by Danuta Czech, Auschwitz Chronicle 1938-1945, pp. 84-87. See the critique of this narrative by Carlo Mattogno, Auschwitz: The First Gassing. Rumor and Reality, 3rd ed., Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield 2016. |

| [2] | Gosudarstvenni Archiv Rossiskoi Federatsii (State Archive of the Russian Federation), Moscow, 7021-108-15, pp. 2f. Subsequently abbreviated as GARF. |

| [3] | Archiwum Głównej Komisji Badania Zbrodni Przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu Instytutu Pamieci Narodowej (Archive of the Central Commission of Inquiry into the Crimes against the Polish People – National Memorial), Warsaw, NTN, 93; subsequently abbreviated as AGK. The report entered the files of the Höss trial in its Volume 11. The quoted passage is on pp. 26f. |

| [4] | Danuta Czech set the date of the first gassing in that morgue to September 16, 1941; see op. cit. (note 1), pp. 89f. |

| [5] | Jan Sehn, Oświęcim-Brzezinka (Auschwitz-Birkenau) Concentration camp, Wydawnictwo Prawnicze, Warsaw 1961, p. 125. |

| [6] | That should be Leichenhalle, as it was above-ground, while “Keller” means basement/cellar. |

| [7] | J.-C. Pressac, Auschwitz: Technique and Operation of the Gas Chambers, The Beate Klarsfeld Foundation, New York 1989, p. 124. |

| [8] | Jadwiga Bezwińska, Danuta Czech (eds.), KL Auschwitz Seen by the SS, Howard Fertig, New York, 1984, p. 93. |

| [9] | Ibid., pp. 96, 115, 134. |

| [10] | Ibid., p. 176. |

| [11] | Minutes of interrogation of Hans Stark, Cologne, April 23, 1959. Zentrale Stelle der Landesjustizverwaltungen, Ludwigsburg, ref. AR-Z 37/58 SB6, p. 947. |

| [12] | This results from a letter dated August 26, 1944, by Heinrich Josten, head of the Auschwitz air-raid protection department, to the camp commandant, Rossiiskii Gosudarstvennii Vojennii Archiv (Russian State War Archive), Moscow, 502-1-401, p. 34. Subsequently abbreviated as RGVA. |

| [13] | RGVA, 502-2-147, p. 12a. |

| [14] | Ditlieb Felderer, “Auschwitz Notebook: Doors & Portholes,” The Journal of Historical Review, Vol. 1, No. 4 (winter 1980), pp. 365-370, here p. 366. |

| [15] | Fred Leuchter, Robert Faurisson, Germar Rudolf, The Leuchter Reports: Critical Edition, Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield 2017, p. 47 |

| [16] | Ernst Gauss (ed.), Grundlagen zur Zeitgeschichte, Grabert, Tübingen 1994, p. 109. |

| [17] | Ernst Gauss (ed.), Dissecting the Holocaust, Theses & Dissertations Press, Capshaw, Ala., 2000, p. 143; Germar Rudolf (ed.), ibid., Chicago, 2003, p. 143. |

| [18] | Carlo Mattogno, Auschwitz: Crematorium I and the Alleged Homicidal Gassings, Theses & Dissertations Press, Chicago, Ill., 2005 (now available in its 2nd ed., Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield 2016). |

| [19] | Germar Rudolf, Lectures on the Holocaust, Theses & Dissertations Press, Chicago, Ill., 2005, p. 255. |

| [20] | Carlo Mattogno, Curated Lies: Auschwitz Museum’s Misrepresentations, Distortions and Deceptions, Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield 2016, pp. 30-32. Similar in my book The Chemistry of Auschwitz, Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield 2017, p. 104. |

| [21] | Hans Jürgen Nowak, Werner Rademacher, “‘Gasdichte’ Türen in Auschwitz,” Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung 2(4) (1998), pp. 248-260. |

| [22] | RGVA 502‑1‑354‑8; July 9, 1942; see Rudolf (ed.), Dissecting the Holocaust, Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield 2019, p. 326. |

Bibliographic information about this document: First published at https://jan27.org/the-thin-internal-walls-of-krematorium-i-at-auschwitz/ in January 2020; here as part of Inconvenient History, Vol. 12, No. 2 (2020)

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a