Working with Stalin

Pal Joey

Joseph Sobran is a nationally-syndicated columnist, lecturer, author (most recently of Alias Shakespeare), and editor of the monthly newsletter Sobran's (PO Box 1383, Vienna, VA 22183). “Pal Joey” is reprinted from the August 1995 issue of Sobran's, and “The Hiss Case” from the January 1997 issue.

Thanks to cable TV, I recently caught up with an old movie I'd somehow missed for half a century: “Mission to Moscow.” I wish everyone could see it; unfortunately, but understandably, it isn't available on video. It richly merits a belated review. You might say it's a time capsule from the Roosevelt Administration.

I'd heard of it, of course. It was a wartime film, made in 1943, long notorious for its shining portrayal of our Soviet allies. Like most old things, it now tells you a lot about its time without intending to.

“Mission to Moscow” is based on a book of the same name by Joseph Davies, Franklin Roosevelt's ambassador to the Soviet Union during the late 1930s. Saul Bellow once called Davies “one of the most disgraceful appointments in the history of diplomacy.” That only sounds like a heated exaggeration until you look for yourself.

I'd always assumed that the movie was the handiwork of Hollywood's Reds, back before the blacklist did its salutary work. Not at all. Jack Warner, of Warner Brothers, made the movie at Roosevelt's urging, after dining with Roosevelt and Davies at the White House. Roosevelt explained that a film version of Davies' book would help the war effort, and Warner patriotically assented on the spot, little knowing what he was in for.

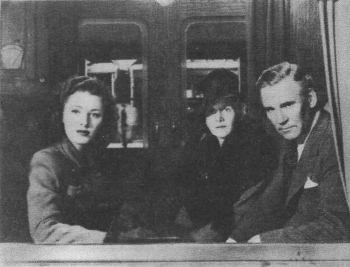

Walter Huston, right, plays the role of US ambassador Joseph Davies in a scene from “Mission to Moscow.” Davies' wife is played by Eleanor Parker, center, and Ann Harding, left, plays their daughter. Directed by Michael Curtiz (born Mikhaly Kertesz), this 1943 Warner Brothers picture flatteringly portrays Soviet dictator Stalin and his regime during the period when the Soviet Union was a close military ally of the United States. Along with “North Star,” “Song of Russia,” “Counter Attack,” and “Days of Glory,” this was one of several pro-Soviet and anti-German films produced by Hollywood during the war to encourage popular acceptance of America's alliance with Soviet Russia.

It was a major production, with Michael Curtiz, who had just won an Oscar for “Casablanca,” directing. The score was composed by Max (“Gone with the Wind”) Steiner. Walter Huston, an excellent actor now best known for “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” (which his son John directed), played Davies. The real Davies appeared in the film before the opening credits to deliver a prologue, in which he explained that he hoped to dispel “prejudice and misunderstanding” about the Soviet Union. Roosevelt was portrayed in the film too, with due reverence: his face was not quite shown, though his voice was heard – much the way Christ used to be portrayed in biblical epics.

In his book, Davies had been a fierce advocate for the Soviets. He admitted that their methods were a little rough at times, but he excused this, as he explained, because of the daunting problems they faced and because Communism (unlike Nazism) was ultimately compatible with Christian ideals. He felt that the show trials were justified, and he considered them successful in their worthy purpose of rooting out traitors. One of his best friends in Moscow was Walter Duranty of the New York Times, who had reported that there was no famine in Ukraine during the early 1930s and won a Pulitzer Prize for journalism.

To help persuade skeptical Americans of the basic righteousness of the Soviet regime, this scene from “Mission to Moscow” sympathetically portrays the Moscow purge trials of the 1930s. In reality these trials were elaborate charades, based on fabricated evidence and confessions extracted by torture, which Stalin staged to destroy his rivals and solidify his grip on power.

The movie matches the book in glorifying Soviet achievements. Set just before the war, when Davies served in Moscow, it shows him traveling to Soviet farms and factories, where happy workers of both sexes are setting new production records. Freud asked a famous question: “What do women want?” “Mission to Moscow” has the answer: they want to make tractors! The only problem the Soviet system faces in the film is a mysterious sabotage campaign.

Back in Moscow, Davies' beaming hosts introduce him to all the Soviet dignitaries, including chief prosecutor Andrei Vishinsky, in real life director of the Gulag system. “We've heard of your famous legal work!” Davies assures him. Vishinsky accepts the compliment with courtly Old World grace.

There are, happily, few Communists in the movie; the term of choice is “the Russians.” The word “Communism” is hardly heard, except in the mouths of the Fascist characters. It's as if using the official name of the system were a sort of smear. Imagine calling Stalin a Communist! (Another “witch-hunt,” presumably.) The Nazi officials Davies encounters in the story are always smiling thinly and saying things like, “Dese Amehicans ah so naive.” And how.

When his subordinates in the US Embassy tell Davies that they suspect the Soviets have bugged the place, Davies tells them not tear the place apart to check it out. First, he doesn't believe it; furthermore, he has nothing to say that he wouldn't say to his Russian hosts' faces; and besides, if the Russians overhear what is really said about them, it may allay their understandable anxieties about foreigners.

And far from dodging the embarrassing topic of the show trials, the movie shows Davies attending them personally, satisfied that the conspirators are sincere in their confessions to having joined Trotsky and the Fascists in the sabotage campaign. Not content with this, the film actually justifies the Hitler-Stalin pact. Davies hears the explanation from Stalin himself, who makes a dramatic appearance late in the film.

Davies opens the conversation by gushing: “I believe that history will record you as a great builder for the benefit of mankind.” Stalin, played as a gentle, wistful pipe-smoking sage with a soft chuckle, modestly demurs. He says that the inspiration was Lenin's, and that “the people themselves” have carried out the great plan. But he warns, in a fatherly way, that “reactionaries” in France and England are trying to set Germany and Russia at war with each other; and little as he likes the Fascists, he will not allow the Russian people to be set up. He implies that he may have no choice, if the West won't oppose Fascism, but to cut a deal with Germany.

As I watched, I reflected that this was why my father fought in World War II. The movie was supposed to convince Americans that their sons were being sent to die in a worthy cause. Unspeakable.

The reviewers who counted, Roosevelt and Stalin, were both well pleased with the film and gave private screenings to entertain guests. Others panned it as shallow propaganda.

Conventional raves and pans are beside the point in this case. To give “Mission to Moscow” its real due, and to put it into proper historical perspective, I would say that it single-handedly vindicates the McCarthy era.

Please don't suspect that I'm exaggerating. We hear a lot about the evils of “Holocaust denial.” But those who question the conventional version of Nazi history are only retrospective and speculative. They don't influence events.

That can't be said for those who assisted and glorified the Soviet Union under Stalin while it was still active and thereby facilitated its enormous crimes. I don't mean Warner Brothers. I mean Joseph Davies. I mean Walter Duranty. And I especially mean the man who inspired this movie, Franklin Roosevelt. Stalin's victims were in part his victims too.

The cynical and mendacious Roosevelt had a strange soft spot for Stalin and Communism. He extended diplomatic recognition to the Soviet Union as soon as he became president, when it was most in need of foreign support and legitimation – even as it was deliberately starving millions. When war came, he didn't regard the alliance with Moscow as a desperate pragmatic move with an unsavory regime with whom he happened to share a common enemy; he envisioned a post-war world in which the “United Nations” would supersede the United States, and in which he and Stalin would lead mankind into an era of global peace and justice.

“Mission to Moscow” captures some of this insane vision. Without meaning to, it shows that the problem of subversion in the Roosevelt Administration went a little higher than Alger Hiss, whom it is hard to blame very much for actions that were only minor replicas of his boss's policies. By 1948 Roosevelt's memory was still so popular that the “witch-hunters” didn't dare point the accusing finger at their proper target; so they settled for investigating the Communist small fry who had flourished under FDR.

The term “McCarthyism” was part of liberalism's strange lexicon of improprieties, the purpose of which was to quash plain speech on touchy subjects by creating an irrational etiquette of discourse. “Mission to Moscow” makes it clear as clear can be that, yes, Roosevelt and his cronies sympathized with Communism, aided it, abetted it, and betrayed America's interests to it. Willing dupes, fellow travelers, pinkoes, Commie-lovers – such words are fair enough for most of them, setting aside the outright Soviet agents. (After all, we aren't expected to split hairs when talking about “fascists,” “racists,” and “reactionaries.”)

Roosevelt himself was no Communist. But he recognized the Soviet Union as the cousin of the New Deal in its general thrust: a huge, arbitrary state, centralized and imperial, unimpeded by such obsolete scruples as personal freedoms and the rule of law. He wanted the American public to be brought to see it as he did.

Jack Warner later came to see “Mission to Moscow” as the worst mistake of his career. Warner Brothers can be pardoned for pitching it down the Memory Hole. But it deserves to be remembered for presenting the official liberal party line as of 1943, precisely because it says things no liberal would dare to say in 1995.

The Hiss Case

Alger Hiss is dead. Finally. He checked out at 92, denying to the last that he had served as a Soviet agent within the Roosevelt Administration. He outlived his accuser, Whittaker Chambers, by 35 years.

I never met either man, though I once saw Hiss, a lonely-looking old man, in a little restaurant in Greenwich Village. I'd read Chambers' famous book, Witness, a combined autobiography and account of the Hiss case, and found it persuasive enough. But I was never absolutely convinced of Hiss' guilt until I heard Hiss himself speak about the case in a recorded address at a New Jersey university. He was so evasive about the essential questions, so facile in playing to his liberal audience, so eager to blame McCarthyite hysteria and Richard Nixon (this just after Nixon's own disgrace) for his fate, that his performance reeked with dishonesty. Not a word about the evil of Communism itself. It wasn't the speech an innocent man would have given.

Documentary evidence that emerged later confirmed Chambers' charges. But I was even more impressed by Hiss' defenders. They didn't really seem to think he was innocent, they seemed to suggest, under all their arguments, that there was nothing really wrong with what he'd done. It was the people who had seen no evil in the Soviet Union, even apologists for Stalin, who insisted most vociferously that Hiss had never been a Soviet agent.

Hiss also had, and has, another sort of partisan. Not all of them insist that he was innocent, many merely continue to speak as if the evidence against him weren't decisive, as if some room for doubt remains. These are generally liberals who fear that Hiss' guilt might implicate the entire Roosevelt Administration in which he rose to a position so near to the boss.

After all, Stalin's best friend in that administration was not Hiss but Roosevelt himself. Hiss was no anomaly. The New Deal was run by other Soviet sympathizers, including Harry Hopkins and Harry Dexter White. Their World War II alliance with the Soviet Union was not merely one of necessity or convenience: they brought real enthusiasm to it. Even as millions were being murdered by forced starvation and incarceration in the Gulag camps, Roosevelt extended diplomatic recognition, legitimacy, and covert aid to the USSR, apart from generous wartime assistance. During the war, official US propaganda portrayed Stalin as a benign and even heroic figure. Hiss did nothing that his superiors hadn't done on a much larger and more fateful scale.

The war resulted in a huge extension of the Soviet empire that engulfed ten Christian countries and issued in the cruelest persecutions of Christians in history. Liberal opinion still treats this outcome as a footnote at best. Stalin's Western partisans still suffer less obloquy than Hitler's, less even than those – Neville Chamberlain, Charles Lindbergh, the “isolationists” – who wanted to avoid war with Hitler. Roosevelt himself remains one of our most venerated presidents.

Not only has Stalin enjoyed, overall, a better press than Hitler (starting with the New York Times), Communists have actually achieved victim status in America, summed up in the devil-term “McCarthyism.” Ex-Communists still write lugubrious memoirs of their sufferings during the Cold War and, more to the point, big publishers still publish them.

As I write, this morning's Times has a review, mildly unfavorable, of Walter Bernstein's Inside Out: A Memoir of the Blacklist (Knopf). No such luck for ex-Nazis, who needn't bother sending their manuscripts to Knopf. Bernstein, a Hollywood screenwriter, finally quit the Communist Party in 1956 after the Soviets crushed the Hungarian uprising. “I knew little about the Gulag,” he is quoted as saying, “and wanted to know less, fearful of its meaning, distrusting the sources of this terrible information.” And he still thinks he got a raw deal because for a decade he couldn't get a job in the movies.

One of the few things that disturbed Bernstein about the Communist motherland was the growing evidence of Soviet anti-Semitism. Never mind the torment of Christians. Such is the disparity of indignation Hitler and Stalin inspire among the intellectuals, even the neoconservative intellectuals. Even after his ruin, Alger Hiss retained some of the privileged moral ambiguity of Communism.

Correction:

There is an error in the article “Auschwitz: Facts and Legend” in the July-August 1997 Journal. Near the top of the left column on page 15, the second paragraph of the quotation should actually be part of the main text. This paragraph, which begins with the words “Soviet propaganda was in disarray … ” should not be indented.

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 16, no. 5 (September/October 1997), pp. 9-12; "Pal Joey" is reprinted from the August 1995 issue of Sobran's, and "The Hiss Case" from the January 1997 issue.

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a