Stalin’s War: A New History of World War II

A Book Review

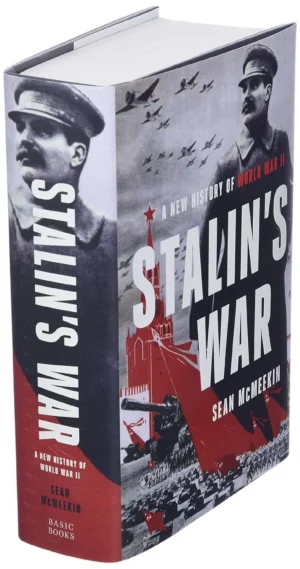

Sean McMeekin is a professor of history at Bard College in upstate New York. Stalin’s War: A New History of World War II is McMeekin’s latest book that focuses on Josef Stalin’s involvement in World War II (New York: Basic Books, 2021; all subsequent page numbers from there). This well-researched and well-written book uses new research in Soviet, European and American archives to prove that World War II was a war that Stalin—not Adolf Hitler—had wanted.

A remarkable feature of Stalin’s War is McMeekin’s documentation showing the extensive aid given by the United States and Great Britain to support Soviet Communism during the war. This article focuses on the lend-lease and other aid given to the Soviet Union during World War II which enabled Stalin to conquer most of Eurasia, from Berlin to Beijing, for Communism.

Communist Agents Promote Stalin

Numerous people sympathetic to Communism and Josef Stalin rose to prominence in U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt’s administration. Among these were Alger Hiss, who was identified by decrypted Soviet telegrams (the Venona files) released to the public in the 1990s as having collaborated with Soviet military intelligence (the GRU). More highly placed was Harry Dexter White, who rose rapidly to become the right-hand man of Henry Morgenthau, Roosevelt’s powerful secretary of the Treasury. Venona decrypts show that White worked for the GRU as early as 1935, and later reported directly to Soviet functionaries working for the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD; pp. 43f.).

There were hundreds of additional paid Soviet agents working inside the U.S. government by the end of the 1930s. From the Departments of Agriculture and State to the Treasury and the U.S. Army, these Soviet agents were placed highly enough to favorably influence policies that affected the Soviet Union. Soviet agent Whittaker Chambers’s handler reported proudly to Moscow, “We have agents at the very center of government, influencing policy.” These Soviet agents in Washington, D.C. provided Stalin with a critical strategic foothold in the American government as he prepared the Soviet Union for war (pp. 44f.).

Roosevelt did everything he could to improve relations with Stalin. In November 1936, Roosevelt appointed a Soviet sympathizer, Joseph Davies, as his ambassador in Moscow, after U.S. Ambassador William Bullitt had become openly critical of Stalin’s regime. Roosevelt also purged the U.S. State Department of anti-Communists in 1937 (pp. 49, 132). McMeekin writes (p. 527):

“Reading through the minutes of Harry Hopkins’s Soviet protocol from 1943, it is hard to escape the impression that Soviet agents of influence had taken over the White House.”

Stalin-friendly journalists such as Walter Duranty of the New York Times and fellow travelers such as George Bernard Shaw also helped cover-up Soviet crimes such as the famine-genocide of the early 1930s and the Great Terror. By contrast, they emphasized German crimes such as the Röhm purge and Kristallnacht. This double standard, when it comes to the public exposure of the crimes of Hitler and Stalin, has continued in the historical literature to this day (pp. 47f.).

The cover-up of the Soviet executions of Polish citizens is a prime example of how Soviet crimes were ignored. McMeekin writes (p. 110):

“The number of victims murdered by Soviet authorities in occupied Poland by June 1941—about 500,000—was likewise three or four times higher than the number of those killed by the Nazis. Amazingly—despite his own war of conquest against Poland being, if not as deadly as Hitler’s during its military phase, then marked by a geometrically larger number of executions and deportations and far more destruction in economic terms—the Vozhd (Stalin) received not even a slap on the wrist from the Western powers for his crimes.”

Lend-Lease Aid Begins

After the German invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, the debate over American aid policy toward Stalin took on world-historical importance, as it had the potential to decide the outcome of the war on the eastern front. While Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill expressed strong support for the Soviet cause, numerous U.S. Congressmen did not share their sentiments. For example, Sen. Robert M. La Follette Jr. warned (p. 350):

“[I]n the next few weeks the American people will witness the greatest whitewash act in all history. They will be told to forget the purges in Russia by the OGPU [secret police], the persecution of religion, the confiscation of property, the invasion of Finland and the vulture role Stalin played in seizing half of prostrate Poland, all of Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania. These will be made to seem the acts of a ‘democracy’ preparing to fight Nazism.”

Despite reservations from many U.S. Congressmen and the majority of the American public, powerful figures in the Roosevelt administration had determined that the Soviet Union would receive lend-lease aid. The Soviet embassy placed its first request for American aid on June 30, 1941. It requested $1.8 billion worth of American warplanes, anti-aircraft guns, toluol (the critical input in TNT), aviation gasoline and lubricants. Roosevelt approved this Soviet request in principle on July 8, and established a special office in the War Department to process military supplies destined for Russia (pp. 352, 354).

Despite reservations from many U.S. Congressmen and the majority of the American public, powerful figures in the Roosevelt administration had determined that the Soviet Union would receive lend-lease aid. The Soviet embassy placed its first request for American aid on June 30, 1941. It requested $1.8 billion worth of American warplanes, anti-aircraft guns, toluol (the critical input in TNT), aviation gasoline and lubricants. Roosevelt approved this Soviet request in principle on July 8, and established a special office in the War Department to process military supplies destined for Russia (pp. 352, 354).

In a later meeting in Moscow, U.S. envoy Harry Hopkins asked Stalin what weapons the Red Army most desperately required. Stalin replied that the Red Army needed anti-aircraft guns, large-caliber machine guns, 7.72 mm caliber rifles, aluminum, and 20,000 pieces of anti-aircraft artillery. After Hopkins agreed to these requests, Stalin proceeded to his second-tier requirements, which included fighters, pursuit planes and medium-range bombers. Hopkins also assented to these requests. Later that night, Hopkins met with Stalin’s artillery expert to discuss technical issues (p. 360).

Hopkins presented Stalin’s material requests to Roosevelt, along with Stalin’s plea that the United States enter the war. Roosevelt agreed to deliver massive volumes of military weapons to the Soviet Union over the coming months, setting aside 100 large transport vessels exclusively for Stalin’s needs. The terms Roosevelt was offering Stalin for this aid were absurdly generous. Roosevelt opened a virtually unlimited credit line (initially $1 billion) to order whatever Stalin desired, in exchange for nothing whatsoever. This $1 billion of strategic exports to Stalin were made without Congressional approval and the American public being informed about it (pp. 364f.).

Despite the United States still being officially neutral in the European war, the Roosevelt administration had gone all in on the Soviet side. Roosevelt’s decision to support Stalin’s war effort in the summer of 1941 was premised on his view that the United States would enter the war against Germany eventually, whether or not most Americans supported Roosevelt’s interventionist policies. These shipments of free aid made a dramatic difference that eventually turned the tide of the entire war in Stalin’s favor (pp. 370-373).

More Lend-Lease Aid

In 1941, the Soviet war industry would not be able to function properly without massive American aid. The United States sent to Stalin’s war factories monthly deliveries of armor plate (1,000 tons), sheet steel (8,000 tons), steel wire (7,000 tons), steel wire rope (1,200 tons), tool steel (500 tons), aluminum ingots (1,000 tons), duralumin (250 tons), tin (4,000 tons), toluol (2,000 tons), ferro chrome (200 tons), ferro silicon (300 tons), rolled brass (5,000 tons), and copper tubes (300 tons; p. 368).

The Red Army lost 20,500 tanks between June and November 1941, amounting to 80% of Stalin’s armored strength (p. 381). The German conquest of industrial areas also caused Soviet tank production to drop from 2,000 to 1,400 tanks per month. Stalin said he needed 2,000 tons of armor plate per month to keep Soviet tank production going at even reduced levels. Roosevelt approved this request, and agreed to supply Stalin with 400 warplanes per month, and monthly shipments of 10,000 American trucks and 5,000 jeeps, 200,000 Red Army boots, 400,000 yards of khaki for uniforms, 1,500 tons of leather hides and boot-sole leather, 200,000 tons of wheat, and 70,000 tons of sugar (pp. 367f.).

Despite the massive American aid to the Soviet Union, the Russians were perennially disappointed in the volume of American lend-lease aid being received in Soviet ports. German U-boats, destroyers, and Luftwaffe air raids frequently sent American cargo to the bottom of the northern Atlantic Ocean or Arctic Sea. The perils of Arctic waves, freezing cold, ice and icebergs, snow and fog also made it difficult for American cargo to reach its intended destination (pp. 390f.).

Soviet purchasing agents had such influence in the Roosevelt administration that, by the spring and summer of 1942, they functioned like members of the U.S. government. The Lend-Lease Administration provided requisition forms to Soviet purchasing agents identical to those used by the U.S. armed forces. This sped up the processing time of Russian requests from an average of 33.2 days in 1941 to 48 hours by January 1942. For all intents and purposes, Stalin’s agents now had legal writ in the United States over essential war supplies (pp. 395f.).

Soviet industrial espionage in the United States took place on a massive scale during World War II. Spying was superfluous in the lend-lease era, as Soviet purchasing agents were allowed to inspect whatever American factories they wished. Soviet purchasing agents could now tell Stalin what to order from the best U.S. aviation factories: Bell, Douglas, and Curtis-Wright. Soviet assets in the U.S. government, like Harry Dexter White, could also casually walk over to the Soviet embassy and suggest reorienting the U.S. machine-tool industry to meet Stalin’s needs. All of these planes, specialized machine tools and other military weapons were delivered to the Soviet Union essentially free of charge (p. 396).

Industrial espionage was easy for Soviet agents to conduct in the United States. In addition to giving Soviet buying agents and engineers free rein to inspect American factories and tank-testing facilities, the transfer of entire American factories to the Soviet Union was approved, including their in-house intellectual property. The process began in July and August 1941, when Roosevelt personally approved contracts to have built in the Soviet Union a $4 million tire plant, a $3 million catalytic plant, a $2.75 million hydrogen plant, a $2.2 million cracking and crude distillation plant, a $1.75 million dehydrocyclization plant, a $1.5 million aviation lubricating oil plant, a $4 million aluminum rolling mill, and a $400,000 high-octane gasoline plant (pp. 397f.).

Lend-lease sharing with the Soviet Union extended even to top-secret military intelligence. McMeekin writes (pp. 401f.):

“Lenin had once prophesied that, after the revolution, capitalists would be happy to sell Communists the rope they would use to hang them. And yet not even Lenin could have imagined that American capitalists would hand over the rope free of charge—and not just any rope either.”

On February 18, 1942, Stalin even requested that the U.S. Navy convoy each shipment of war supplies from the East Coast all the way to the Soviet Arctic. Roosevelt granted Stalin’s request. In March 1942, Roosevelt ordered Adm. Emory S. Land to “give Russia first priority in shipping” and take merchant vessels off Latin American and Caribbean routes “regardless of other considerations.” Roosevelt ordered Russian shipments to be prioritized “regardless of the effect…on any other part of our war program” (pp. 404f.). Thus, Stalin’s requests were given priority over all other military operations.

Lend-Lease Turns War in Stalin’s Favor

In the first seven or eight months of 1942, the German Luftwaffe dominated Soviet airspace, and German armored divisions enjoyed parity at worst and often considerable local superiority over the Red Army’s depleted supply of tanks. However, once lend-lease supplies began arriving in the Soviet Union in appreciable quantities, the material equation began to shift in Stalin’s favor (p. 416).

Interestingly, while much has been written about the superiority of Russian tanks such as the T-34 to comparable American and British models, in private Russian experts conceded that U.S. and British tanks had many positive aspects. American M-3 Stuart light and medium tanks were found to produce a “high density of fire.” The medium Stuart M-3 had “excellent visibility from the perspective of the commander,” while the light M-3 had “superior mobility.” The light and medium Stuart tanks were well designed ergonomically, with “convenient crew placement,” and were quieter than many Soviet models. At Stalin’s request, Roosevelt ordered American tanks to be retrofitted to meet Soviet needs (p. 418).

Roosevelt also sent a large number of Jeeps and trucks to help the Red Army. Studebaker trucks were outfitted with 76 mm Red Army guns and placed into immediate use, playing a crucial role in supplying mobile forces deployed beyond railheads. American jeeps proved immensely popular with Russian drivers because of their maneuverability and versatility. In addition to the 36,865 trucks and 6,823 jeeps delivered to the Soviet Union by June 30, 1942, between 25,000 and 30,000 more arrived by mid-November 1942, when the Red Army was preparing its counteroffensive to cut off Stalingrad (pp. 423f.).

At Stalin’s request, Roosevelt began sending 5,000 tons of aluminum per month to help build Soviet tanks. Soviet shortages of other nonferrous metals—including nickel, ferrochrome, and ferrosilicon—were filled by the Americans, who supplied Stalin with 800 tons per month of each of these important industrial metals. American shipments of specialty steels for military use were also sent to the Soviet Union. Roosevelt sent 4,000 to 5,000 tons per month of TNT and other high explosives to help the Soviets at Stalingrad. Finally, 300 tons of the weather-resistant vulcanized rubber compound called Vistanex was sent for use in the separation plates in Soviet tank and airplane batteries (pp. 425f.).

American lend-lease aid was crucial in helping the Red Army defeat the Germans at Stalingrad. Such lend-lease aid included 70,000 trucks and jeeps, 500,000 tons of American aviation and motor fuel and lubricants, 4,469 tanks and gun carriers, 1,663 warplanes, and tons of numerous food items to help feed Red Army soldiers. McMeekin writes, “[I]t is an imperishable historical fact that the Anglo-American capitalism helped win the battle of Stalingrad” (pp. 430-432).

Lend-Lease Aid Wins War for Stalin

Lend-lease aid meant that if Stalin simply bided his time, the surpluses of American capitalism would allow his armored divisions to keep growing. From July 1, 1942 to June 30, 1943, the United States shipped more than 3.4 million tons of goods to Stalin, including barbed wire (4,000 tons shipped each month), 120,000 machine guns, another 120,000 Thompson submachine guns, anti-tank mines (60,000 per month), 5,117 anti-aircraft guns, 24 million square yards of tarpaulin, 75,000 tons of oil pipe and tubing, 181,366 tons of TNT, 173,000 field telephones, 580,000 miles of telephone wire, and 220,000 tons of petroleum products, most of it refined aviation gasoline. Numerous additional Allied lend-lease shipments were crucial in the battle at Kursk (p. 462).

The Germans had nothing to match the sheer volume of supplies Stalin’s armies were receiving each month. By the time the Germans struck at Kursk in July 1943, ratios in manpower, tanks and self-propelled guns favored the Soviets by more than three to one, in warplanes by more than four to one, and in guns and artillery pieces by five or six to one. These advantages were compounded by the fact that the Russians could choose and fortify their ground for defense. Kursk was a decisive battle which marked the failure of the last major German offensive on the eastern front in the war. This victory was made possible by Allied lend-lease aid and complementary U.S.-British landings in Sicily (pp. 436, 466, 473).

Stalin was also given first priority in regard to foodstuffs. American civilians were forced to provide Russians with food at a time of strict wartime rationing back home. So colossal were shipments of lend-lease foodstuffs to Stalin that by 1943 many American store shelves were emptied of essentials. Some 8,000 rationing boards in the United States during the war restricted consumption of everything from grain, milk, butter, and sugar to fuel, rubber, tires, fabrics and shoes. The most famous lend-lease foodstuff given to Russians during the war—Spam—was so highly prized by the Red Army that the American pork and meat-canning industry was reshaped to meet Soviet demand. A special manual was prepared and distributed to each Red Army unit explaining what foods were in the cans and packets they had received from the American lend-lease program (pp. 522-526).

Numerous American plants and refineries were dismantled and shipped to the Soviet Union. These include a Ford Tire Plant, a Douglas oil refinery, 11 hydroelectric plants, and a steel rail mill. The volume of U.S. industrial equipment shipped from July 1, 1943 to June 30, 1944 was 739,000 tons, with a dollar value of $401 million. McMeekin writes (pp. 527f.):

“Even before the third protocol period began in July 1943, Stalin’s procurement agents had already requisitioned $500 million worth of ‘industrial equipment’—an amount comparable to $50 billion today—consisting of everything from machine tools, electric furnaces, motors, cranes, and hoists to oil refineries, tire manufacturing plants, and aluminum and steel-rolling mills.”

Remarkably, lend-lease aid to the Soviet Union continued after Germany had been defeated. On May 10—two days after VE Day—U.S. President Harry Truman signed a presidential directive curtailing Soviet aid shipments sent to Europe, since the war in Europe was over. This reasonable directive was vigorously protested by Soviet officials. On May 27, 1945, Hopkins met with Stalin in Moscow. Stalin lit into Hopkins over the “scornful and abrupt,” “unfortunate and brutal” way Truman had cut off the supplies Stalin had been receiving. Stalin had the audacity to tell Hopkins that if American refusal to continue lend-lease aid was designed as pressure on the Russians, then it was a fundamental mistake that might result in reprisals (pp. 633f.).

Conclusion

The approximately $11 billion in military weapons, industrial equipment, technology and intellectual property given to Stalin was crucial in helping him win the war. The Soviet wartime debts were written off in 1951 at two cents on the dollar. By contrast, Great Britain paid its debts in full, with interest, until 2006 (pp. 658f.).

When measured by territory conquered and war booty received, Stalin was the victor in both Europe and Asia. No one else came close. The three Axis powers were totally crushed. France was a withered wreck and soon lost its empire. Great Britain was bankrupt and moribund. Although the United States was relatively untouched by the war at home and emerged in a strong position, the Cold War required a gargantuan expenditure over decades, until the Soviet Union eventually collapsed in 1991 (pp. 663-665).

The effect of lend-lease aid to Stalin was the expansion of Communism and the Soviet Union’s empire. McMeekin writes (pp. 665f.):

“The ultimate price of victory was paid by the tens of millions of involuntary subjects of Stalin’s satellite regimes in Europe and Asia, including Maoist China, along with the millions of Soviet dissidents, returned Soviet POWs, and captured war prisoners who were herded into Gulag camps from the Arctic gold and platinum mines of Vorkuta to the open-air uranium strip mines of Stavropol and Siberia. For subjects of his expanding slave empire, Stalin’s war did not end in 1945. Decades of oppression and new forms of terror were still to come.”

Some Critical Remarks about Sean McMeekin’s Book Stalin’s War

Sean McMeekin’s latest book Stalin’s War: A New History of World War II is a well-researched book that documents that World War II was a war that Josef Stalin—not Adolf Hitler—had wanted. McMeekin describes the literature on World War II as excessively German-centric. For Americans, Australians, Britons, Canadians and Western Europeans, World War II has always been Hitler’s war.[1]

McMeekin states that, starting with the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in September 1931 and ending with Japan’s final capitulation in September 1945, there were numerous wars on the planet. It would be a stretch to blame them all on Hitler, since Hitler was not in power in Germany when the Manchurian conflict erupted, and had been dead four months before Japan surrendered. McMeekin writes:[2]

“[I]t would make far more sense to choose someone who was alive and in power during the whole thing, whose armies fought in both Asia and Europe on a regular (if not uninterrupted) basis for the entire period, whose empire spanned the Eurasian continent that furnished the theater for most of the fighting and nearly all of the casualties, whose territory was coveted by the two main Axis aggressors, and who succeeded in defeating them both and massively enlarging his empire in the process—emerging, by any objective evaluation, as the victor inheriting the spoils of war, if at a price in Soviet lives (nearly 30 million) so high as to be unfathomable today. In all these ways, it was not Hitler’s, but Stalin’s, war.”

As much as I admire McMeekin’s extensive research and focus on Stalin as the primary aggressor and beneficiary of World War II, he makes statements in Stalin’s War that I don’t agree with. This article focuses on these statements and conclusions that I think are either questionable or erroneous.

Hitler’s Declaration of War on the United States

Like most establishment historians, McMeekin writes that Adolf Hitler made a foolish mistake declaring war against the United States in his speech on December 11, 1941.[3] However, U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt’s numerous provocations made it extremely difficult for Hitler not to declare war against the United States.

Roosevelt signed the Lend-Lease Act into law on March 11, 1941. This legislation marked the end of any pretense of neutrality on the part of the United States. Despite soothing assurances by Roosevelt that the United States would not get into the war, the adoption of the Lend-Lease Act was a decisive move which put America into an undeclared war in the Atlantic. It opened up an immediate appeal for naval action to ensure that munitions and supplies procured under the Lend-Lease Act would reach Great Britain.[4]

The first wartime meeting between Roosevelt and Churchill began on August 9, 1941, in a conference at the harbor of Argentia in Newfoundland. The principal result of this conference was the signing of the Atlantic Charter on August 14, 1941. Roosevelt repeated to Churchill during this conference his predilection for an undeclared war, saying, “I may never declare war; I may make war. If I were to ask Congress to declare war, they might argue about it for three months.”

The Atlantic Charter was in effect a joint declaration of war aims, although Congress had not voted for American participation in the war. The Atlantic Charter, which provided for Anglo-American cooperation in policing the world after the Second World War, was a tacit but inescapable implication that the United States would soon become involved in the war. This implication is fortified by the large number of top military and naval staff personnel who were present at the conference.[5]

Roosevelt’s next move toward war was the issuing of secret orders on August 25, 1941, to the Atlantic Fleet to attack and destroy German and Italian “hostile forces.” These secret orders resulted in an incident on September 4, 1941, between an American destroyer, the Greer, and a German submarine.[6] Roosevelt falsely claimed in a fireside chat to the American public on September 11, 1941, that the German submarine had fired first.

The reality is that the Greer had tracked the German submarine for three hours, and broadcast the submarine’s location for the benefit of any British airplanes and destroyers which might be in the vicinity. The German submarine fired at the Greer only after a British airplane had dropped four depth charges which missed their mark. During this fireside chat Roosevelt finally admitted that, without consulting Congress or obtaining congressional sanction, he had ordered a shoot-on-sight campaign against Axis submarines.[7]

On September 13, 1941, Roosevelt ordered the Atlantic Fleet to escort convoys in which there were no American vessels.[8] This policy would make it more likely to provoke future incidents between American and German vessels. Roosevelt also agreed about this time to furnish Britain with “our best transport ships.” These included 12 liners and 20 cargo vessels manned by American crews to transport two British divisions to the Middle East.[9]

More serious incidents followed in the Atlantic. On October 17, 1941, an American destroyer, the Kearny, dropped depth charges on a German submarine. The German submarine retaliated and hit the Kearny with a torpedo, resulting in the loss of 11 lives. An older American destroyer, the Reuben James, was sunk with a casualty list of 115 of her crew members.[10] Some of her seamen were convinced the Reuben James had already sunk at least one U-boat before she was torpedoed by the German submarine.[11]

Japan’s attack against the United States on December 7, 1941, at Pearl Harbor was the result of Roosevelt’s numerous provocations against Japan. On December 8, 1941, President Roosevelt made a speech to Congress calling for a declaration of war against Japan. Condemning the attack on Pearl Harbor as a “date which will live in infamy,” Roosevelt did not once mention Germany.

Hitler’s policy of keeping incidents between the United States and Germany to a minimum seemed to have succeeded. Hitler had ignored or downplayed the numerous provocations that Roosevelt had made against Germany. Even after Roosevelt issued orders to shoot-on-sight at German submarines, Hitler had ordered his naval commanders and air force to avoid incidents that Roosevelt might use to bring America into the war. Also, since the Tripartite Pact did not obligate Germany to join Japan in a war initiated by Japan, it appeared unlikely that Hitler would declare war on the United States.[12]

Hitler’s decision to stay out of war with the United States was made more difficult on December 4, 1941, when the Chicago Tribune carried in huge black letters the headline: F.D.R.’s WAR PLANS! The Washington Times Herald, the largest paper in the nation’s capital, carried a similar headline.

Chesly Manly, the Tribune’s Washington correspondent, revealed in his report what Roosevelt had repeatedly denied: that Roosevelt was planning to lead the United States into war against Germany. The source of Manly’s information was no less than a verbatim copy of Rainbow Five, the top-secret war plan drawn up at Roosevelt’s request by the joint board of the United States Army and Navy. Manly’s story even contained a copy of President Roosevelt’s letter ordering the preparation of the plan.[13]

Rainbow Five called for the creation of a 10-million-man army, including an expeditionary force of 5 million men that would invade Europe in 1943 to defeat Germany. On December 5, 1941, the German Embassy in Washington, D.C., cabled the entire transcript of the newspaper story to Berlin. The story was reviewed and analyzed in Berlin as “the Roosevelt War Plan.” On December 6, 1941, Adm. Erich Raeder submitted a report to Hitler prepared by his staff that analyzed the Rainbow Five plan. Raeder concluded the most important point contained in Rainbow Five was the fact that the United States would not be ready to launch a military offensive against Germany until July 1943.[14]

On December 9, 1941, Hitler returned to Berlin from the Russian front and plunged into two days of conferences with Raeder, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, and Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring. The three advisors stressed that the Rainbow Five plan showed that the United States was determined to defeat Germany. They pointed out that Rainbow Five stated that the United States would undertake to carry on the war against Germany alone even if Russia collapsed and Britain surrendered to Germany. The three advisors leaned toward Adm. Raeder’s view that an air and U-boat offensive against both British and American ships might be risky, but that the United States was already unquestionably an enemy.[15]

On December 9, 1941, Roosevelt made a radio address to the nation that is seldom mentioned in the history books. In addition to numerous uncomplimentary remarks about Hitler and Nazism, Roosevelt accused Hitler of urging Japan to attack the United States. Roosevelt declared:[16]

“We know that Germany and Japan are conducting their military and naval operations with a joint plan. Germany and Italy consider themselves at war with the United States without even bothering about a formal declaration…Your government knows Germany has been telling Japan that if Japan would attack the United States, Japan would share the spoils when peace came. She was promised by Germany that if she came in, she would receive control of the whole Pacific area and that means not only the Far East, but all the islands of the Pacific and also a stranglehold on the west coast of North and Central and South America.”

All of the above statements are obviously lies. Germany and Japan did not have a joint naval plan before Pearl Harbor, and never concocted one for the rest of the war. Germany did not have foreknowledge and certainly never encouraged Japan to attack the United States. Japan never had any ambition to attack the west coast of North, Central, or South America. Germany also never promised anything to Japan in the Far East. Germany’s power in the Far East was negligible.[17]

Roosevelt concluded in his speech on December 9, 1941:[18]

“We expect to eliminate the danger from Japan, but it would serve us ill if we accomplished that and found that the rest of the world was dominated by Hitler and Mussolini. So, we are going to win the war and we are going to win the peace that follows.”

On December 10, 1941, when Hitler resumed his conference with Raeder, Keitel, and Göring, Hitler said that Roosevelt’s speech confirmed everything in the Tribune story. Hitler considered Roosevelt’s speech to be a de facto declaration of war. Since war with the United States was inevitable, Hitler felt he had no choice but to declare war on the United States.

McMeekin describes Hitler’s unilateral declaration of war on the United States as “a move so self-sabotaging as to defy explanation to this day.” McMeekin writes:[19]

“Some have suggested that Rainbow Five was leaked by the president himself to goad Hitler into declaring war. If true, this was a brilliant political coup.”

The truth, however, is that Roosevelt did everything in his power to plunge the United States into war against Germany. In addition to the Lend-Lease Act and numerous other provocations, Roosevelt eventually went so far as to order American vessels to shoot-on-sight German and Italian vessels—a flagrant act of war. Hitler had wanted to avoid war with the United States at all costs. Hitler expressly ordered German submarines to avoid conflicts with U.S. warships, except to prevent imminent destruction. It appeared that Hitler’s efforts would be successful in keeping the United States out of the war against Germany.

Hitler, however, declared war on the United States after the leaked Rainbow Five plan convinced him that war with the United States was inevitable. It was not a self-sabotaging move as McMeekin suggests. The extraordinary cunning of leaking Rainbow Five at the very time he knew a Japanese attack was pending enabled Roosevelt to overcome the American public’s resistance to entering the war. It allowed the entry of the United States into World War II in such a way as to make it appear that Germany and Japan were the aggressor nations.[20]

The Holocaust Hoax

Establishment historians all uphold the official Holocaust story. For example, historian Brendan Simms writes:[16]

“Finally, Hitler’s central role in the murder of 6 million Jews has been proven beyond all doubt by Richard Evans, Peter Longerich and others involved in the rebuttal of David Irving’s claims to the contrary.”

In reality, as I have shown in previous articles for Inconvenient History, Richard Evans and Peter Longerich have never proven that 6 million Jews were murdered in the so-called Holocaust.[22]

McMeekin also believes in the Holocaust story and makes numerous references to the “Holocaust” in Stalin’s War. For example, he writes:[23]

“Stalin’s intentions in stipulating various categories of kulak (capitalist) peasant households fit for deportation may not have been as explicitly murderous as the Wannsee Protocols (though many Ukrainians, and some historians, now believe they were), but the results were unquestionably genocidal.”

As I have shown in an article for Inconvenient History, contrary to McMeekin’s statement, there is no “explicitly murderous” language in the Wannsee Protocols.[24]

McMeekin also states that Hitler’s greatest crime was the ongoing mass murder of European Jewry, which had begun on the eastern front in 1941, and picked up momentum with the construction of death camps in German-occupied Poland in 1942. He writes:[25]

“To this day, controversy rages about what might have been done to slow down the Holocaust, whether via Allied bombing runs on the train lines running to the death camps of Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, and Auschwitz or, in one gruesome what-if scenario, by aerial bombing of the camps themselves—the idea being that even death by friendly fire was preferable to the terrible fate that awaited Jews, Roma, and others gassed by the Germans.”

McMeekin fails to acknowledge in this passage that there were no homicidal gas chambers in any of the German camps, and that Germany did not have a program of genocide against Jews during World War II.[26]

McMeekin also uses the so-called Holocaust as a partial reason why U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau recommended his infamous Morgenthau Plan. He writes:[27]

“Morgenthau’s own blood was clearly up, at least in part out of genuine conviction. The secretary was Jewish, which gave him a personal stake in holding Hitler and the Germans responsible for the ongoing mass murder of European Jewry. Like Roosevelt with unconditional surrender in 1943, Morgenthau had sincere personal reasons for advocating the policy line that he did, even if it did dovetail neatly with Soviet foreign policy objectives.”

Contrary to McMeekin’s statement, Germany did not have an ongoing program of mass murder of European Jewry. The “Holocaust” should not be used as a partial excuse for the American adoption of the lethal Morgenthau Plan.

McMeekin also credits the Soviet liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau with saving Jewish lives. He writes:[28]

“By month’s end, Soviet troops had also liberated Auschwitz-Birkenau, saving about 7,500 emaciated Jewish survivors of this soon-notorious Nazi death camp.”

Contrary to McMeekin’s statement, since Germany did not have an extermination program against Jews, the Soviets did not save any Jewish lives when they liberated Auschwitz-Birkenau. The Germans, if they had an extermination program, could have gassed and cremated the remaining Jews in crematorium V at Auschwitz-Birkenau during the first week of January 1945 before the Soviets arrived.[29]

Finally, McMeekin writes:[30]

“In late September, after the Germans occupied Kiev, more than 33,000 Jews were slaughtered at Babi Yar outside the city, in a grim foreshadowing of still greater horrors to come.”

However, as I have shown in a previous article for Inconvenient History, an air photo taken of the ravine of Babi Yar on September 26, 1943 shows a placid and peaceful valley. Neither the vegetation nor the topography has been disturbed by human intervention. There are no burning sites, no smoke, no excavations, no fuel depots, and no access roads for the transport of humans or fuel. We can conclude with certainty from this photo that no part of Babi Yar was subjected to topographical changes of any magnitude right up to the Soviet reoccupation of the area. Hence, the mass graves and mass cremations attested to by witnesses at Babi Yar did not take place.[31]

Hitler’s Preemptive Invasion of the Soviet Union

McMeekin also questions whether Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, was made for preemptive reasons. He writes:[32]

“The proximate cause for this decision, judging from Hitler’s remarks at the time and subsequently, was Stalin’s effort to blackmail him in November and December 1940, not anything related to Soviet mobilization.”

Hitler, however, made it very clear in his speech on December 11, 1941, why he had invaded the Soviet Union. Hitler said:[33]

“When I became aware of the possibility of a threat to the east of the Reich in 1940 through reports from the British House of Commons and by observations of Soviet Russian troop movements on our frontiers, I immediately ordered the formation of many new armored, motorized and infantry divisions. The human and material resources for them were abundantly available….

We realized very clearly that under no circumstances could we allow the enemy the opportunity to strike first into our heart. Nevertheless, the decision in this case was a very difficult one. When the writers for the democratic newspapers now declare that I would have thought twice before attacking if I had known the strength of the Bolshevik adversaries, they show that they do not understand either the situation or me.

I have not sought war. To the contrary, I have done everything to avoid conflict. But I would forget my duty and my conscience if I were to do nothing in spite of the realization that a conflict had become unavoidable. Because I regarded Soviet Russia as a danger not only for the German Reich but for all of Europe, I decided, if possible, to give the order myself to attack a few days before the outbreak of this conflict.

A truly impressive amount of authentic material is now available which confirms that a Soviet Russian attack was intended. We are also sure about when this attack was to take place. In view of this danger, the extent of which we are perhaps only now truly aware, I can only thank the Lord God that He enlightened me in time and has given me the strength to do what must be done. Millions of German soldiers may thank Him for their lives, and all of Europe for its existence.

I may say this today: If this wave of more than 20,000 tanks, hundreds of divisions, tens of thousands of artillery pieces, along with more than 10,000 airplanes, had not been kept from being set into motion against the Reich, Europe would have been lost.”

Hitler was speaking the truth in this speech. McMeekin also mentions numerous facts in Stalin’s War that support Hitler’s claim that his invasion of the Soviet Union was made for preemptive reasons. For example, McMeekin writes:[34]

“As noted earlier, the Red Army had lost 20,500 tanks between June and November 1941, amounting to 80% of Stalin’s armored strength.”

This confirms Hitler’s statement that the Soviet Union had more than 20,000 tanks available to attack Europe.

McMeekin writes that, in November 1939, the Red Army was the largest, most mechanized, most heavily armored, and most lavishly armed army in the world.[35] The Soviet economy had been on a war footing since the first Five-Year Plan was inaugurated in 1928. McMeekin writes:[36]

“The production targets of the third Five-Year Plan, launched in 1938, were breathtaking, envisioning the production of 50,000 warplanes annually by the end of 1942, along with 125,000 air engines and 700,000 tons of aerial bombs; 60,775 tanks, 119,060 artillery systems, 450,000 machine guns, and 5.2 million rifles; 489 million artillery shells, 120,000 tons of naval armor, and 1 million tons of explosives; and, for good measure, 298,000 tons of chemical weapons. While not all of these targets were realistic or met, progress in the most critical areas—such as tanks, anti-tank guns, and warplanes—was striking. By the end of 1940, the Red Army deployed 23,307 operational tanks, 15,000 45 mm anti-tank guns, and 22,171 warplanes, with thousands more state-of-the-art models of each coming on line in 1941. In these areas, the Red Army was the world’s most formidable. The Wehrmacht, by comparison, had only 3,387 panzers on hand prior to the invasion of France in May 1940…”

The offensive nature of Stalin’s army is confirmed in a speech Stalin made on May 5, 1941, to an elite audience of 2,000 military academy graduates in the Andreevsky Hall in the Moscow Kremlin. Stalin said that, since the Soviet-Finnish war, the USSR had “reconstructed our army and armed it with modern military equipment.” The Red Army had grown from 120 to more than 300 divisions, with greatly improved Soviet tanks, artillery, aviation, anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns.[37]

The head of the Frunze Military Academy, Lt. Gen. M. S. Khozin, spoke after Stalin finished his speech. Parroting the Pravda propaganda line of the day, Khozin saluted Stalin for the success of his “peace policy,” which had kept the Soviet Union out of the “capitalist war” raging in Europe and Asia. Before Khozin could finish his speech, Stalin leapt to his feet and reproached Khozin for promoting an “out of date policy.”[38]

Stalin told the officers and party bosses present that the “Soviet peace policy” had bought the Red Army time to modernize and rearm, while also allowing the USSR to “push forward in the west and north, increasing its population by 13 million in the process.” However, Stalin said the days of peaceful absorption of new territory “had come to an end. Not another foot of ground can be gained with such peaceful sentiments.” Stalin continued, “But today, now that our army has been thoroughly reconstructed, fully outfitted for fighting a modern war, now that we are strong—now we must shift from defense to offense.”[39]

Hitler invaded the Soviet Union to prevent Stalin’s planned invasion of Germany and all of Europe. For more information on this subject, I recommend the book The Chief Culprit: Stalin’s Grand Design to Start World War II by Viktor Suvorov.[40]

Lax Security?

McMeekin correctly writes that large numbers of Soviet and Communist agents infiltrated the U.S. government during Roosevelt’s administration. A critical factor enabling this infiltration was Roosevelt’s recognition of Stalin’s regime, which removed the stigma from Communist Party membership. McMeekin says another factor in this infiltration was Soviet opportunism, enabled by the Roosevelt administration’s lax security.[41]

In this author’s opinion, however, it was Roosevelt’s enthusiastic support of Stalin’s regime rather than lax security that allowed Soviet agents to infiltrate the U.S. government. Roosevelt was always a good friend of Josef Stalin. Roosevelt indulged in provocative name-calling against the heads of totalitarian nations such as Germany, Italy and Japan, but never against Stalin or the Soviet Union.[42] Roosevelt always spoke favorably of Stalin, and American wartime propaganda referred to Stalin affectionately as “Uncle Joe.”

Roosevelt’s attitude toward Stalin is remarkable considering that his first appointed ambassador to the Soviet Union, William Bullitt, warned Roosevelt of the danger of supporting Stalin. Bullitt served as America’s first ambassador to the Soviet Union from November 1933 to 1936. Bullitt left the Soviet Union with few illusions, and by the end of his tenure he was openly hostile to the Soviet government. Bullitt stated in his final report from Moscow on April 20, 1936, that the Russian standard of living was possibly lower than that of any other country in the world. Bullitt reported that the Bulgarian Comintern leader, Dimitrov, had admitted that the Soviet popular front and collective security tactics were aimed at undermining the foreign capitalist systems. Bullitt concluded that relations of sincere friendship between the Soviet Union and the United States were impossible.[43]

Roosevelt was fully aware of the slave-labor system, the liquidation of the kulaks, the man-made famine, the extreme poverty and backwardness, and the extensive system of espionage and terror that existed in the Soviet Union. However, from the very beginning of his administration, Roosevelt sang the praises of a regime which recognized no civil liberties whatsoever. In an attempt to gain swift Congressional approval for Lend-Lease aid to the Soviet Union, Roosevelt even said that Stalin’s regime was at the forefront of “peace and democracy in the world.” At a White House press conference, Roosevelt also claimed that there was freedom of religion in the Soviet Union.[44]

The Soviet Union had been a totalitarian regime since 1920. By the time Hitler’s National Socialist Party came to power in 1933, the Soviet government had already murdered millions of its own citizens. The Soviet terror campaign accelerated in the late 1930s, resulting in the murder of many more millions of Soviet citizens as well as thousands of American citizens working in the Soviet Union. Many Americans lost their entire families in the Soviet purge of the late 1930s. Despite these well-documented facts, the Roosevelt administration fully supported the Soviet Union.[45]

Roosevelt was basically in the Soviet’s pocket. He admired Stalin, and sought his favor. Roosevelt thought the Soviet Union indispensable in the war, crucial to bringing world peace after it, and he wanted the Soviets handled with kid gloves. The Russians hardly could have done better if Roosevelt was a Soviet spy.[46] Thus, it was not lax security, but rather Roosevelt’s enthusiastic support of Stalin’s regime that caused so many Soviet agents to infiltrate the U.S. government.

Conclusion

McMeekin in Stalin’s War makes another statement I don’t agree with. In regard to British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s speech on March 31, 1939, guaranteeing Poland’s independence, McMeekin writes:[47]

“Hitler read the loose guarantee of Polish ‘independence’ as a green light for adjusting Poland’s borders.”

Hitler, however, invaded Poland only because of numerous atrocities committed by the Polish government against the German minority in Poland that occurred after Chamberlain’s speech guaranteeing Poland’s independence.[48]

McMeekin also twice incorrectly states that Gen. Sir Alan Brooke was Winston Churchill’s air chief.[49] Actually, Sir Arthur Harris was the commander-in-chief of British Bomber Command from February 23, 1942 until the end of the war.

Despite my disagreement with some of McMeekin’s statements in Stalin’s War, I thoroughly enjoyed reading this book. McMeekin has done extensive research that is not found in many World War II history books. He has properly shown Stalin to be the primary aggressor and beneficiary of the Second World War.

Notes

| [1] | McMeekin, Sean, Stalin’s War: A New History of World War II, New York: Basic Books, 2021, pp. 1, 5. |

| [2] | Ibid., pp. 2-3. |

| [3] | Ibid., pp. 2, 658. |

| [4] | Chamberlain, William Henry, America’s Second Crusade, Chicago: Regnery, 1950, p. 130. |

| [5] | Sanborn, Frederic R., “Roosevelt is Frustrated in Europe,” in Barnes, Harry Elmer (ed.), Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace, Newport Beach, Cal: Institute for Historical Review, 1993, pp. 217-218. |

| [6] | Ibid., p. 218. |

| [7] | Chamberlain, William Henry, America’s Second Crusade, Chicago: Regnery, 1950, pp. 147-148. |

| [8] | Hearings Before the Joint Committee on the Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack, 79 Cong., 2 sess., 39 parts; Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1946, Part V, p. 2295. |

| [9] | Churchill, Winston S., The Grand Alliance, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1950, pp. 492-493. |

| [10] | Chamberlain, William Henry, America’s Second Crusade, Chicago: Regnery, 1950, pp. 148-149. |

| [11] | Newsweek, November 10, 1941, p. 35. |

| [12] | Meskill, Johanna Menzel, Hitler and Japan: The Hollow Alliance, New York: 1955, p. 40. |

| [13] | Fleming, Thomas, The New Dealers’ War: FDR and the War within World War II, New York: Basic Books, 2001, p. 1. |

| [14] | Ibid., pp. 1-2, 33. |

| [15] | Ibid., pp. 33-34. |

| [16] | Ibid., pp. 34-35. |

| [17] | Meskill, Johana Menzel, Hitler and Japan: The Hollow Alliance, New York: 1955, pp. 1-47. |

| [18] | http://millercenter.org/president/fdroosevelt/speeches/speech-3325. |

| [19] | McMeekin, Sean, Stalin’s War: A New History of World War II, New York: Basic Books, 2021, p. 386. |

| [20] | http://www.veteranstoday.com/2008/06/16/rainbow-5-roosevelts-secret-pre-pearl-harbor-war-plan-exposed/. |

| [21] | Simms, Brendan, Hitler: A Global Biography, New York: Basic Books, 2019, p. xxi. |

| [22] | Wear, John, “Peter Longerich on the ‘Holocaust,’“ Inconvenient History, Vol. 13, No. 3, 2021 and Wear, John, “Richard J. Evans: The New Wave of ‘Court’ Historian,” Inconvenient History, Vol. 13, No. 1, 2021. |

| [23] | McMeekin, Sean, Stalin’s War: A New History of World War II, New York: Basic Books, 2021, pp. 26-27. |

| [24] | Wear, John, “Wannsee: The Road to the Final Solution,” Inconvenient History, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2022. |

| [25] | McMeekin, Sean, Stalin’s War: A New History of World War II, New York: Basic Books, 2021, p. 448. |

| [26] | See Wear, John, “The Chemistry of Auschwitz/Birkenau,” Inconvenient History, Vol. 9, No. 4, 2017. |

| [27] | McMeekin, Sean, Stalin’s War: A New History of World War II, New York: Basic Books, 2021, p. 571. |

| [28] | Ibid., p. 600. |

| [29] | Mattogno, Carlo, Auschwitz: The Case for Sanity, Washington, D.C.: The Barnes Review, 2010, p. 558. |

| [30] | McMeekin, Sean, Stalin’s War: A New History of World War II, New York: Basic Books, 2021, p. 322. |

| [31] | Wear, John, “Babi Yar,” Inconvenient History, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2018. |

| [32] | McMeekin, Sean, Stalin’s War: A New History of World War II, New York: Basic Books, 2021, p. 280. |

| [33] | Weber, Mark, “The Reichstag Speech of 11 December 1941: Hitler’s Declaration of War Against the United States,” The Journal of Historical Review, Vol. 8, No. 4, Winter 1988-1989, pp. 395-396. |

| [34] | McMeekin, Sean, Stalin’s War: A New History of World War II, New York: Basic Books, 2021, p. 381. |

| [35] | Ibid., p. 119. |

| [36] | Ibid., pp. 219-220. |

| [37] | Ibid., pp. 7-9. |

| [38] | Ibid., p. 9. |

| [39] | Ibid. |

| [40] | Suvorov, Viktor, The Chief Culprit: Stalin’s Grand Design to Start World War II, Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 2008. |

| [41] | McMeekin, Sean, Stalin’s War: A New History of World War II, New York: Basic Books, 2021, pp. 42-43. |

| [42] | Fish, Hamilton, FDR The Other Side of the Coin: How We Were Tricked into World War II, New York: Vantage Press, 1976, pp. 8, 16. |

| [43] | Hoggan, David L., The Forced War: When Peaceful Revision Failed, Costa Mesa, Cal.: Institute for Historical Review, 1989, p. 423. |

| [44] | Tzouliadis, Tim, The Forsaken: An American Tragedy in Stalin’s Russia, New York: The Penguin Press, 2008, p. 204. |

| [45] | Ibid., pp. 100-102, 105, 127. |

| [46] | Wilcox, Robert K., Target: Patton, Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing, Inc., 2008, pp. 250-251. |

| [47] | McMeekin, Sean, Stalin’s War: A New History of World War II, New York: Basic Books, 2021, p. 71. |

| [48] | Wear, John, “Why Germany Invaded Poland,” Inconvenient History, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2019. |

| [49] | McMeekin, Sean, Stalin’s War: A New History of World War II, New York: Basic Books, 2021, pp. 500, 506. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 2022, Vol. 14, No. 2

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a