World War I on the Home Front

The changes wrought in America during the First World War were so profound that one scholar has referred to “the Wilsonian Revolution in government.”[1] Like other revolutions, it was preceded by an intellectual transformation, as the philosophy of progressivism came to dominate political discourse.[2] Progressive notions – of the obsolescence of laissez-faire and of constitutionally limited government, the urgent need to “organize” society “scientifically,” and the superiority of the collective over the individual – were propagated by the most influential sector of the intelligentsia and began to make inroads in the nation’s political life.

As the war furnished Lenin with otherwise unavailable opportunities for realizing his program, so too, on a more modest level, it opened up prospects for American progressives that could never have existed in peacetime. The coterie of intellectuals around the New Republic discovered a heaven-sent chance to advance their agenda. John Dewey praised the “immense impetus to reorganization afforded by this war,” while Walter Lippmann wrote: “We can dare to hope for things which we never dared to hope for in the past.” The magazine itself rejoiced in the war’s possibilities for broadening “social control … subordinating the individual to the group and the group to society,” and advocated that the war be used “as a pretext to foist innovations upon the country.”[3]

Woodrow Wilson’s readiness to cast off traditional restraints on government power greatly facilitated the “foisting” of such “innovations.” The result was a shrinking of American freedoms unrivaled since at least the War Between the States.

It is customary to distinguish “economic liberties” from “civil liberties.” But since all rights are rooted in the right to property, starting with the basic right to self-ownership, this distinction is in the last analysis an artificial one.[4] It is maintained here, however, for purposes of exposition.

As regards the economy, Robert Higgs, in his seminal work, Crisis and Leviathan, demonstrated the unprecedented changes in this period, amounting to an American version of Imperial Germany’s Kriegssozialismus. Even before we entered the war, Congress passed the National Defense Act. It gave the president the authority, in time of war “or when war is imminent,” to place orders with private firms which would “take precedence over all other orders and contracts.” If the manufacturer refused to fill the order at a “reasonable price as determined by the Secretary of War,” the government was “authorized to take immediate possession of any such plant [and] … to manufacture therein … such product or material as may be required”; the private owner, meanwhile, would be “deemed guilty of a felony.”[5]

Once war was declared, state power grew at a dizzying pace. The Lever Act alone put Washington in charge of the production and distribution of all food and fuel in the United States.

By the time of the armistice, the government had taken over the ocean-shipping, railroad, telephone, and telegraph industries; commandeered hundreds of manufacturing plants; entered into massive enterprises on its own account in such varied departments as shipbuilding, wheat trading, and building construction; undertaken to lend huge sums to business directly or indirectly and to regulate the private issuance of securities; established official priorities for the use of transportation facilities, food, fuel, and many raw materials; fixed the prices of dozens of important commodities; intervened in hundreds of labor disputes; and conscripted millions of men for service in the armed forces.

Fatuously, Wilson conceded that the powers granted him “are very great, indeed, but they are no greater than it has proved necessary to lodge in the other Governments which are conducting this momentous war.”[6] So, according to the president, the United States was simply following the lead of the Old-World nations in leaping into war socialism.

Throngs of novice bureaucrats eager to staff the new agencies overran Washington. Many of them came from the progressive intelligentsia. “Never before had so many intellectuals and academicians swarmed into government to help plan, regulate, and mobilize the economic system” – among them Rexford Tugwell, later the key figure in the New Deal Brain Trust.[7] Others who volunteered from the business sector harbored views no different from the statism of the professors. Bernard Baruch, Wall Street financier and now head of the War Industries Board, held that the free market was characterized by anarchy, confusion, and wild fluctuations. Baruch stressed the crucial distinction between consumer wants and consumer needs, making it clear who was authorized to decide which was which. When price controls in agriculture produced their inevitable distortions, Herbert Hoover, formerly a successful engineer and now food administrator of the United States, urged Wilson to institute overall price controls: “The only acceptable remedy [is] a general price-fixing power in yourself or in the Federal Trade Commission.” Wilson submitted the appropriate legislation to Congress, which, however, rejected it.[8]

Ratification of the Income Tax Amendment in 1913 paved the way for a massive increase in taxation once America entered the war. Taxes for the lowest bracket tripled, from 2 to 6 percent, while for the highest bracket they went from a maximum of 13 percent to 77 percent. In 1916, less than half a million tax returns had been filed; in 1917, the number was nearly 3.5 million, a figure which doubled by 1920. This was in addition to increases in other federal taxes. Federal tax receipts “would never again be less than a sum five times greater than prewar levels.”[9]

But even huge tax increases were not nearly enough to cover the costs of the war. Through the recently established Federal Reserve System, the government created new money to finance its stunning deficits, which by 1918 reached $1 billion a month – more than the total annual federal budget before the war. The debt, which had been less than $1 billion in 1915, rose to $25 billion in 1919. The number of civilian federal employees more than doubled, from 1916 to 1918, to 450,000. After the war, two-thirds of the new jobs were eliminated, leaving a “permanent net gain of 141,000 employees – a 30 percent ‘ratchet effect.'”[10]

Readers who might expect that such a colossal extension of state control provoked a fierce resistance from heroic leaders of big business will be sorely disappointed. Instead, businessmen welcomed government intrusions, which brought them guaranteed profits, a “riskless capitalism.” Many were particularly happy with the War Finance Corporation, which provided loans for businesses deemed essential to the war effort. On the labor front, the government threw its weight behind union organizing and compulsory collective bargaining. In part, this was a reward to Samuel Gompers for his territorial fight against the nefarious IWW, the Industrial Workers of the World, which had ventured to condemn the war on behalf of the working people of the country.[11]

* * *

Of the First World War, Murray Rothbard wrote that it was “the critical watershed for the American business system … [a war-collectivism was established] which served as the model, the precedent, and the inspiration for state corporate capitalism for the remainder of the century.”[12] Many of the administrators and principal functionaries of the new agencies and bureaus reappeared a decade and a half later, when another crisis evoked another great surge of government activism. It should also not be forgotten that Franklin Roosevelt himself was present in Washington, as assistant secretary of the navy, an eager participant in the Wilsonian revolution.

The permanent effect of the war on the mentality of the American people, once famous for their devotion to private enterprise, was summed up by Jonathan Hughes:

The direct legacy of war – the dead, the debt, the inflation, the change in economic and social structure that comes from immense transfers of resources by taxation and money creation – these things are all obvious. What has not been so obvious has been the pervasive yet subtle change in our increasing acceptance of federal nonmarket control, and even our enthusiasm for it, as a result of the experience of war.[13]

Civil liberties fared no better in this war to make the world safe for democracy. In fact, “democracy” was already beginning to mean what it means today – the right of a government legitimized by formal majoritarian processes to dispose at will of the lives, liberty, and property of its subjects. Wilson sounded the keynote for the ruthless suppression of anyone who interfered with his war effort: “Woe be to the man or group of men that seeks to stand in our way in this day of high resolution.” His attorney general Thomas W. Gregory seconded the president, stating, of opponents of the war:[14]

“May God have mercy on them, for they need expect none from an outraged people and an avenging government.”

By Underwood & Underwood [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The New York Times, then as now the mouthpiece of the powers that be, goaded the authorities to “make short work” of IWW “conspirators” who opposed the war, just as the same paper applauded Nicholas Murray Butler, president of Columbia, for “doing his duty” in dismissing faculty members who opposed conscription. The public schools and the universities were turned into conduits for the government line. Postmaster General Albert Burleson censored and prohibited the circulation of newspapers critical of Wilson, the conduct of the war, or the Allies.[16] The nation-wide campaign of repression was spurred on by the Committee on Public Information, headed by George Creel, the US government’s first propaganda agency.

In the cases that reached the Supreme Court the prosecution of dissenters was upheld. It was the great liberal, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., who wrote the majority decision confirming the conviction of a man who had questioned the constitutionality of the draft, as he did also in 1919, in the case of Debs, for his antiwar speech.[17] In the Second World War, the Supreme Court of the United States could not, for the life of it, discover anything in the Constitution that might prohibit the rounding up, transportation to the interior, and incarceration of American citizens simply because they were of Japanese descent. In the same way, the Justices, with Holmes leading the pack, now delivered up the civil liberties of the American people to Wilson and his lieutenants.[18] Again, precedents were established that would further undermine the people’s rights in the future. In the words of Bruce Porter:[19]

“Though much of the apparatus of wartime repression was dismantled after 1918, World War I left an altered balance of power between state and society that made future assertions of state sovereignty more feasible – beginning with the New Deal.”

We have all been made very familiar with the episode known as “McCarthyism,” which, however, affected relatively few persons, many of whom were, in fact, Stalinists. Still, this alleged time of terror is endlessly rehashed in schools and media. In contrast, few even among educated Americans have ever heard of the shredding of civil liberties under Wilson’s regime, which was far more intense and affected tens of thousands.

The worst and most obvious infringement of individual rights was conscription. Some wondered why, in the grand crusade against militarism, we were adopting the very emblem of militarism. The Speaker of the House Champ Clark (D-Mo.) remarked that “in the estimation of Missourians there is precious little difference between a conscript and a convict.” The problem was that, while Congress had voted for Wilson’s war, young American males voted with their feet against it. In the first ten days after the war declaration, only 4,355 men enlisted; in the next weeks, the War Department procured only one-sixth of the men required. Yet Wilson’s program demanded that we ship a great army to France, so that American troops were sufficiently “blooded.” Otherwise, at the end the president would lack the credentials to play his providential role among the victorious leaders. Ever the deceiver and self-deceiver, Wilson declared that the draft was “in no sense a conscription of the unwilling; it is, rather, selection from a nation which has volunteered in mass.”[20]

Wilson, lover of peace and enemy of militarism and autocracy, had no intention of relinquishing the gains in state power once the war was over. He proposed postwar military training for all 18- and 19-year-old males and the creation of a great army and a navy equal to Britain’s, and called for a peacetime sedition act.[21]

Two final episodes, one foreign and one domestic, epitomize the statecraft of Woodrow Wilson.

At the new League of Nations, there was pressure for a US “mandate” (colony) in Armenia, in the Caucasus. The idea appealed to Wilson; Armenia was exactly the sort of “distant dependency” which he had prized 20 years earlier, as conducive to “the greatly increased power” of the president. He sent a secret military mission to scout out the territory. But its report was equivocal, warning that such a mandate would place us in the middle of a centuries-old battleground of imperialism and war, and lead to serious complications with the new regime in Russia. The report was not released. Instead, in May 1920, Wilson requested authority from Congress to establish the mandate, but was turned down.[22] It is interesting to contemplate the likely consequences of our Armenian mandate, comparable to the joy Britain had from its mandate in Palestine, only with constant friction and probable war with Soviet Russia thrown in.

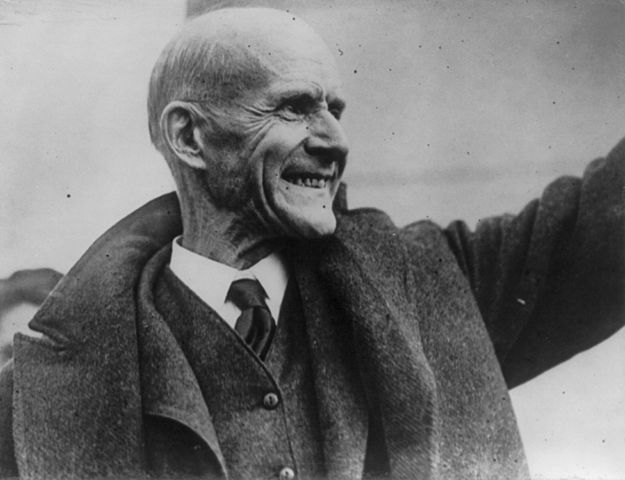

In 1920, the United States – Wilson’s United States – was the only nation involved in the World War that still refused a general amnesty to political prisoners.[23] The most famous political prisoner in the country was the Socialist leader Eugene Debs. In June 1918, Debs had addressed a Socialist gathering in Canton, Ohio, where he pilloried the war and the US government. There was no call to violence, nor did any violence ensue. A government stenographer took down the speech, and turned in a report to the federal authorities in Cleveland. Debs was indicted under the Sedition Act, tried and condemned to ten years in federal prison.

In January 1921, Debs was ailing, and many feared for his life. Amazingly, it was Wilson’s rampaging attorney general A. Mitchell Palmer himself who urged the president to commute Debs’s sentence. Wilson wrote across the recommendation the single word, “Denied.” He claimed that “while the flower of American youth was pouring out its blood to vindicate the cause of civilization, this man, Debs, stood behind the lines, sniping, attacking, and denouncing them […] he will never be pardoned during my administration.”[24] Actually, Debs had denounced not “the flower of American youth” but Wilson and the other war-makers who sent them to their deaths in France. It took Warren Harding, one of the “worst” American Presidents according to numerous polls of history professors, to pardon Debs, when Wilson, a “Near-Great,” would have let him die a prisoner. Debs and 23 other jailed dissidents were freed on Christmas Day, 1921. To those who praised him for his clemency, Harding replied:[25]

“I couldn’t do anything else. […] Those fellows didn’t mean any harm. It was a cruel punishment.”

An enduring aura of saintliness surrounds Woodrow Wilson, largely generated in the immediate post-World War II period, when his “martyrdom” was used as a club to beat any lingering isolationists. But even setting aside his role in bringing war to America, and his foolish and pathetic floundering at the peace conference – Wilson’s crusade against freedom of speech and the market economy alone should be enough to condemn him in the eyes of any authentic liberal. Yet his incessant invocation of terms like “freedom” and “democracy” continues to mislead those who choose to listen to self-serving words rather than look to actions. What the peoples of the world had in store for them under the reign of Wilsonian “idealism” can best be judged by Wilson’s conduct at home.

Walter Karp, a wise and well-versed student of American history, though not a professor, understood the deep meaning of the regime of Woodrow Wilson:[26]

“Today, American children are taught in our schools that Wilson was one of our greatest Presidents. That is proof in itself that the American Republic has never recovered from the blow he inflicted on it.”

October 15, 2012

Notes:

This article appeared at Lew Rockwell.com at: http://archive.lewrockwell.com/raico/raico51.1.html

Copyright © 2012 by the Ludwig von Mises Institute. Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided full credit is given.

| [1] | Bruce D. Porter, War and the Rise of the State: The Military Foundations of Modern Politics (New York: Free Press, 1993), p. 269. |

| [2] | Arthur A. Ekirch, Jr., Progressivism in America: A Study of the Era from Theodore Roosevelt to Woodrow Wilson (New York: New Viewpoints, 1974); and Robert Higgs, Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), pp. 113–16. See also Murray N. Rothbard’s essay on “World War I as Fulfillment: Power and the Intellectuals,” in John V. Denson, ed., The Costs of War: America’s Pyrrhic Victories, Second Edition (New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction, 2001) pp. 249–99. |

| [3] | David M. Kennedy, Over There: The First World War and American Society (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), pp. 39–40, 44, 246; Ekirch, Decline of American Liberalism, (London: Longman Green, 1955), p. 205. |

| [4] | See Murray N. Rothbard, The Ethics of Liberty (New York: New York University Press, 1998 [1982]). |

| [5] | Higgs, Crisis and Leviathan, pp. 128–29. |

| [6] | Higgs, Crisis and Leviathan, pp. 123, 135. |

| [7] | Murray N. Rothbard, “War Collectivism in World War I,” in Ronald Radosh and Murray N. Rothbard, eds., A New History of Leviathan: Essays on the Rise of the American Corporate State (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1972), pp. 97–98. Tugwell lamented, in Rothbard’s words, that “only the Armistice prevented a great experiment in control of production, control of price, and control of consumption.” |

| [8] | Kennedy, Over There, pp. 139–41, 243. Kennedy concluded, p. 141: “under the active prodding of war administrators like Hoover and Baruch, there occurred a marked shift toward corporatism in the nation’s business affairs. Entire industries, even entire economic sectors, as in the case of agriculture, were organized and disciplined as never before, and brought into close and regular relations with counterpart congressional committees, cabinet departments, and Executive agencies.” On Hoover, see Murray N. Rothbard, “Herbert Clark Hoover: A Reconsideration,” New Individualist Review (Indianapolis, Ind.: Liberty Press, 1981), pp. 689–98, reprinted from New Individualist Review, vol. 4, no. 2 (Winter 1966), pp. 1–12. |

| [9] | Kennedy, Over There, p. 112. Porter, War and the Rise of the State, p. 270. |

| [10] | Jonathan Hughes, The Governmental Habit: Economic Controls from Colonial Times to the Present (New York: Basic Books, 1977), p. 135; Kennedy, Over There, pp. 103–13; Porter, War and the Rise of the State, p. 271. |

| [11] | Kennedy, Over There, pp. 253–58; Hughes, The Governmental Habit, p. 141. Hughes noted that the War Finance Corporation was a permanent residue of the war, continuing under different names to the present day. Moreover, “subsequent administrations of both political parties owed Wilson a great debt for his pioneering ventures into the pseudo-capitalism of the government corporation. It enabled collective enterprise as ‘socialist’ as any Soviet economic enterprise, to remain cloaked in the robes of private enterprise.” Rothbard, “War Collectivism in World War I,” p. 90, observed that the railroad owners were not at all averse to the government takeover, since they were guaranteed the same level of profits as in 1916–17, two particularly good years for the industry. |

| [12] | Rothbard, “War Collectivism in World War I,” p. 66. |

| [13] | Hughes, The Governmental Habit, p. 137. See also Higgs, Crisis and Leviathan, pp. 150–56. |

| [14] | Quotations from Wilson and Gregory in H. C. Peterson and Gilbert C. Fite, Opponents of War, 1917–1918 (Seattle, Wash.: University of Washington Press, 1968 [1957]), p. 14. |

| [15] | Ibid., pp. 30–60, 157–66, and passim. |

| [16] | Ekirch, Decline of American Liberalism, pp. 217–18; Porter, War and the Rise of the State, pp. 272–74; Kennedy, Over There, pp. 54, 73–78. Kennedy comments, p. 89, that the point was reached where “to criticize the course of the war, or to question American or Allied peace aims, was to risk outright prosecution for treason.” |

| [17] | Ray Ginger, The Bending Cross: A Biography of Eugene Victor Debs (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1949), pp. 383–84. Justice Holmes complained of the “stupid letters of protest” he received following his judgment on Debs: “there was a lot of jaw about free speech,” the Justice said. See also Kennedy, Over There, pp. 84–86. |

| [18] | See the brilliant essay by H. L. Mencken, “Mr. Justice Holmes,” in idem, A Mencken Chrestomathy (New York: Vintage, 1982 [1949]), pp. 258–65. Mencken concluded: “To call him a Liberal is to make the word meaningless.” Kennedy, Over There, pp. 178–79 pointed out Holmes’s mad statements glorifying war. It was only in war that men could pursue “the divine folly of honor.” While the experience of combat might be horrible, afterwards “you see that its message was divine.” This is reminiscent less of liberalism as traditionally understood than of the world-view of Benito Mussolini. |

| [19] | Porter, War and the Rise of the State, p. 274. On the roots of the national-security state in the World War I period, see Leonard P. Liggio, “American Foreign Policy and National-Security Management,” in Radosh and Rothbard, A New History of Leviathan, pp. 224–59. |

| [20] | Peterson and Fite, Opponents of War, p. 22; Kennedy, Over There, p. 94; Higgs, Crisis and Leviathan, pp. 131–32. See also the essay by Robert Higgs, “War and Leviathan in Twentieth Century America: Conscription as the Keystone,” in Denson, ed., The Costs of War, pp. 375–88. |

| [21] | Kennedy, Over There, p. 87; Ekirch, Decline of American Liberalism, pp. 223–26. |

| [22] | Carl Brent Swisher, American Constitutional Development, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin, 1954), pp. 681–82. |

| [23] | Ekirch, Decline of American Liberalism, p. 234. |

| [24] | Ginger, The Bending Cross, pp. 356–59, 362–76, 405–06. |

| [25] | Peterson and Fite, Opponents of War, p. 279. |

| [26] | Karp, The Politics of War: The Story of Two Wars Which Altered Forever the Political Life of the American Republic (1890-1920) (New York: Harper & Row, 1979), p. 340. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 5(4) (2013); This article appeared at Lew Rockwell.com at: http://archive.lewrockwell.com/raico/raico51.1.html

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a