Atomic War Crimes

The further one seriously studies history, and particularly the World War Two period, the more striking is the disconnect between what is popularly believed and what actually happened. Perhaps the reading public continues to shrink, not only in the United States but around the world, while information and opinion are generally retrieved from television and popular films, this in spite of the serious scholarship going on these areas and the many excellent published works in this field. What cutting-edge research demonstrates is often completely at odds with what one views on the big screen and television.

Popular television pseudo-documentary programming continues to purvey certain myths and untruths about World War Two as if they were established facts, the “final word” on the subject of interpretations of events. Former White House personality Lt. Col. Oliver North, for example, has frequently been seen on cable television’s The History Channel and elsewhere, stating as “fact” that the United States used the atom bomb in order to (a) force the Japanese to surrender, and (b) thus prevent an otherwise necessary US military invasion of Japan. Thus, the use of the atom bomb “saved lives”—the figure of one million being commonly cited—and was an act of statesmanship if not heroism.[1] This myth was first conveyed to the American people and the world in the closing days of World War Two by the Truman administration and a largely uncritical, compliant mass print and radio media. The American public commonly trusted their government and what it told them, and this bit of fanciful propaganda was not questioned at the time. Later, however, criticisms did arise but were not widely accepted. The “saving of lives” myth has endured as a common belief for well over half a century right down to the present day. The endurance of this set of myths was further exemplified by the uproar over the 1994-5 “Enola Gay” exhibit at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., from those angry at the perceived deviation from the patriotic myth of the bomb used to end the war and save lives.

The truth is that the atomic bombings were unnecessary in a military sense with regard to Japan, and the decision to use them had almost nothing to do with Japan at all, and far more to do with the projection of American power and influence elsewhere in the world.

Tracing the evolution of this appalling story is useful in numerous regards. It begins in the early war period, as American president Franklin Roosevelt gave audience to a leading scientist named Albert Einstein. Einstein expressed the concern that Nazi Germany had a program to develop a superweapon that could destroy whole cities in one strike and that if the United States did not develop a similar weapon before the Germans did, that the latter could win the war with it. FDR was convinced and authorized what came to be known as the “Manhattan Project,” which worked to develop the atomic bomb.[2]

Einstein was representative of a group of physicists, many of whom were (a) Jewish, and (b) politically communist. Many of these men were present or former members of various communist parties in Europe or the USA.[3] These men were “refugees” from internments and other security actions under the Nazi aegis taking place in Europe, and had taken up residence in a welcoming USA. Their collective animus towards Nazi Germany and the intention to subject it and/or Nazi-controlled Europe to atomic bombings were not in question. This private, political agenda came to influence leading American politicians and their policy formulation.

The United States devoted billions of research dollars to the Manhattan Project, which neared completion by the early summer of 1945. The received history is somewhat different up to this point. The physicists group’s dominant ethnicity and political leanings are left unmentioned, and their work is usually couched within terms of merely wishing to assist America in repelling the great danger emanating from Nazi Europe, and developing a super-weapon to enable America to attain an ability to combat this supposed evil or danger.

However, events played out somewhat differently from their expectations. The war in Europe ended before the bomb was completed, and thus its contemplated use there was abandoned. Victory in Europe (“VE-Day”) came in May 1945 and the first atomic test did not occur until about mid-July. A post-war Europe was already being carved up by the victorious allies, who had agreed to meet at Potsdam, Germany to work out their differences and make the final decisions on the fate of the world. This left the war in the Pacific as the only unresolved area of conflict and the only possible target area for the bomb.

The mythic story line is that the Japanese were stubbornly refusing to surrender, that their nation was dominated by a radicalized military clique who wished the nation to fight to the last island and even to the last man, and that in consequence an invasion of the Japanese home islands by American forces would be necessary to end the war. Such an invasion would cost, it was estimated, at least a million lives and would take many months—if not years—of hard and bloody fighting. It is well known today, and largely undisputed among scholars that Japan actually was ready to surrender and had already been putting out peace feelers to the United States through its diplomats in the Vatican, Portugal, Sweden, and in Moscow.

A dramatic move in this direction was taken by the Japanese emperor himself, in transmitting to the Soviet Union a request to accept the emperor’s personal representative Prince Konoye as an envoy to formalize a surrender. The United States had been routinely deciphering and reading Japanese diplomatic and military codes and was well aware of these peace moves and of Japan’s disastrous situation by 1945. Clearly it had been thoroughly “beaten” by strategic bombing and naval blockade and was looking for a way out. Secret strategic intelligence studies carried out by the US military demonstrated that Japan would likely surrender within a few months, and that an invasion was not necessary. Even a paucity of targets demonstrated that Japan was at its end and that a naval blockade alone would bring about surrender. Japan was cut off from its armies on the Asian mainland and could thus not count on reinforcement. The home islands were reduced to starvation levels. Its navy had been destroyed. Its industrial capacity was by now nearly nonexistent, having been bombed into oblivion by the ever-present American air forces.

The intelligence reports and summaries, however, were secret in nature, as was the fact that America had broken the Japanese codes and was aware of its internal situation and communications. The American public believed that Japan still retained the strength and purpose to continue fighting for perhaps years to come and had both the means and the suicidal determination to defend itself against an invasion.

Terms of acceptable surrender consisted of a sort of oral “unconditional surrender” mantra. The expression itself was never an official or defined American policy and had originated in a speech given by President Franklin Roosevelt soon after Pearl Harbor in 1941. The American perception was that the Axis powers would have to completely and absolutely give in to the Allies without any preconditions or terms whatsoever. Although a politically popular “feel good” slogan with the public, among military leaders it quickly came to be seen as something which hardened resistance and prolonged the war—thus unnecessarily lengthening American casualty lists and consuming enormous national treasure.[4]

By late 1944, most American political and military leaders were advising the President to define surrender terms to Japan, including a proviso allowing for the retention of the Emperor. It was clearly understood from Japanese peace feelers, decoded secret intercepts, and intelligence reports that the Japanese would accept virtually any and all terms from the victor with the sole exception of the Emperor’s status which to the Japanese was non-negotiable, as the Emperor represented Japan’s essence and was viewed as a semi-divine being vital for the continuation of Japan physically, culturally, and spiritually. It was also clearly understood that (a) Japan would not surrender without such a proviso, and that (b) America needed the Emperor and his cooperation to ensure a laying down of arms, a spirit of postwar cooperation, and an orderly occupation. Truman was convinced and the 1945 Potsdam Declaration in its draft stage did contain such a proviso; however, at Byrne’s urging it was deleted before its transmission to Japan and the world. Byrnes did not want the war to end just yet; his policy was to continue the war long enough to employ both types of bombs and in as bloody and impressive a way as possible to have a psychological effect upon the Russians. Ultimately, the surrender was “conditional” as it did allow for the Mikado’s retention. Hirohito’s unprecedented 1945 radio address did in fact order surrender to the Japanese people and allowed America to achieve its goals in Japan – certainly something very difficult if not impossible were the Emperor to have been dethroned or tried as a war criminal.

Advice and opinion relayed to Truman from US Army Generals Marshall, Eisenhower, and MacArthur, US Army Air Force Generals Le May, Spaatz, and Arnold, from US Navy Admirals Nimitz, Leahy, and King, Secretary of the Navy Forrestal, Secretary of War Stimson, Secretary of State Stettinius and Acting Secretary of State Grew—and many others—were a solid collective voice to Truman to not use the bomb, not invade Japan, to formulate America’s war aims and soften “unconditional surrender” in something more acceptable to Japan. Such voices had largely convinced the president until Jimmy F. Byrnes’s decisive influence on Truman reversed his view and re-oriented policy along harder lines.

General Eisenhower expressed misgivings aforehand to the use of the bomb, as “unnecessary” and “horrible.” His somewhat moralistic approach to the atomic bomb is interesting, given his own personal history and doings. He oversaw the carpet – and incendiary-bombing of German cities in which hundreds of thousands of civilians died, as well as the very high death tolls of prisoners retained in camps in Western Europe in the early postwar period; recategorized from POWs to DEPS, their Geneva convention protections were removed and they were typically denied food, medical care, or shelter, resulting in a very high death rate.

To explain this policy reversal, a diplomatic digression is in order. Truman had appointed Byrnes as his secretary of state in mid-1945. Byrnes had been a close friend and mentor of Truman’s from the latter’s entry into politics many years earlier, and had been a strong associate of Roosevelt also. He had taken Truman under his personal and political wing and influenced his success, even though Byrnes reportedly viewed Truman as a not-so-intelligent nonentity. The 1944 selection of FDR’s running mate fell upon Truman almost accidentally, and was widely thought that it should have gone to Byrnes instead.[5] His accession to the presidency on FDR’s passing in early 1945 left Truman with feelings of doubt and guilt, as well as confusion and a need to turn to his long-time mentor Byrnes to help him formulate policy. The two men “went way back” and regularly drank and played poker together in a “good ole boys” atmosphere that transcended party politics. Truman correctly felt that he owed Byrnes a great deal and needed his wise counsel. Thus the tremendous, even decisive, influence of Byrnes over Truman in this period is not so surprising.

As for Byrnes’s motivations and agenda, it was both personal and political. At the time of the Yalta accords with the Russians, Byrnes had served as FDR’s point man and spokesman for those agreements, and had returned to America to advocate them as good and enforceable policy. Indeed it could be said that his personal and political reputation was closely intertwined with those accords. It gradually emerged, however, that the accords were not so good for the world, that they served Soviet purposes more than American, that their terms and understandings were vague and open to various interpretations, and also that the Russians intended to interpret them their own way and to act strictly in accordance with their own goals. This could hugely backfire on Byrnes, and politically this was becoming a disaster for American policy and for Byrnes personally. By 1945 it was becoming clear to American leaders that the Russians were going to be very difficult to deal with. They were already shaping Europe to fit their own designs, and had plans for Asia too, especially after their early-anticipated declaration of war upon Japan and the imminent Red Army invasion of Manchuria.

The final development of America’s new superweapon offered a possible solution to these problems. It was thought that the Russians could or would be “impressed” by it, but to achieve this, (a) the bomb would have to be actually used, (b) it would have to be used in combat, (c) it would have to be used in a truly dramatic way, and (d) maximum “shock” effect could only be attained through its unannounced use and preferably over a major city. Usage of the bomb thus became more political than military in that it would make the Russians more “manageable” in Europe and Asia. American leaders with this “big stick” in hand, would “control” the Russians and achieve American goals around the world. This was the essential

reasoning of Byrnes in his formulation of American foreign policy, and Truman became convinced.

The Potsdam meeting with the “Big Three” (USA, USSR, and Britain) was postponed until America could gets its test results of the atomic bomb. If the results were a success, America would have the superweapon. If not, it would have to remain conciliatory and continue to compromise with the Soviets. The reports duly came in that the results were even greater than anticipated. Truman immediately took a harder line with the Russians and made the final decision to use the bomb on Japan—and regardless of surrender possibilities, loss of life, or any moral or ethical considerations—even regardless of the continued near-unanimous advice of his military and political leaders to not use the bomb and to accept Japan’s surrender. Using the bomb in as dramatic a method as possible, would serve as both carrot and stick to the only emerging superpower that could challenge the United States in world affairs: a “carrot” in the “we might share this with you if…” sense, and a “stick” as in “cooperate or…”

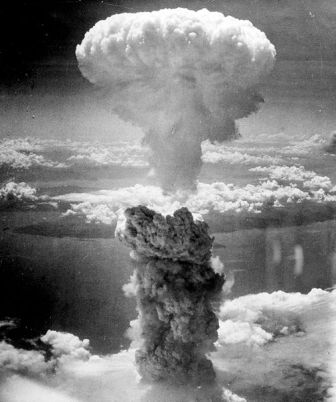

The tragic events unfolded. Two Japanese cities were bombed and nearly 150,000 lives were taken as a result of each event—a figure including the later deaths from radiation poisoning, injuries, etc.[6] Japan was not forced to surrender by the bomb, it was already prepared to surrender many months earlier, and America knew it but did not act on that fact. The war itself was not shortened by the bomb, in fact it was prolonged by at least several weeks if not months longer than necessary. Lives were not saved, they were wasted: hundreds of thousands of lives were squandered in order for the United States to attempt to achieve a political effect with the Soviet Union. Ironically, the effect was ultimately not achieved at all, as the psychological impact upon the Russians was limited and they continued to go their own way in Europe, achieved their goals in Asia, and much of the world fell into their control. Far from “controlling” the Soviets, they became less trusting and more truculent, and a “cold war” soon commenced while the world became divided into two major camps engaged in a hugely expensive and dangerous arms race.

There are numerous interesting asides to this story, all worthy of further research and comment.

The Jewish physicists resisted the use of the bomb on Japan and made representations to Truman accordingly. Their somewhat genocidal view towards Germany amazingly metamorphosed into a more ethical and moral humanitarian approach once the likely target had shifted from Europe to Asia. These same physicists had also urged Truman to share the new weapon and its technology with the world—which primarily meant sharing it with the Soviet Union—in the interests of “lessening tensions” and reaching some sort of utopian world peace and amity. This advice was not taken seriously and not followed. A number of these men were later uncovered as atomic spies, passing technology secrets to the Soviets and enabling them to develop their own bomb, thus plunging the world into a state of nuclear terror lasting many decades and bringing the world very close to the brink of destruction at least once.[7] Scores of thousands of nuclear weapons piled up around the world. That terror persists to this day, and arguably the nuclear dangers are more profound in the modern world than they were during the “cold war” period of international tension, as the technology to produce these weapons proliferates amongst smaller and “rogue” nations and regimes as scientists and technologists are more willing and able to sell the necessary secrets and components.

Ramifications of international and military law are explicitly damning. The intentional targeting of civilians and the use of poisons against anyone—radiation poisoning easily falling into this category—is prohibited. Only days after Hiroshima, the August 8, 1945 treaty was signed in London which established the legal basis for the Nuremberg and Tokyo War Crimes trials. A day later, Nagasaki too was bombed. No American military or political leader has ever been prosecuted for these crimes, while many Germans and Japanese were tried, convicted, and executed for far less serious actions. To what degree this troubles the world, or troubles the American conscience, remains unknown.

In later years, popular distaste for the use of atomic bombs began to threaten reputations. Criticisms and informed reassessments began surfacing, in response to which “damage control” and “spin-doctoring” went into play by those whose place in history were at stake. Byrnes, for example, in postwar interviews attempted to shift responsibility to the “Interim Committee”—purportedly an advisory group set up by the president—for having made the recommendation to Truman to use the bomb. In actuality the committee was a sort of rubber stamp group which Byrnes dominated as the president’s personal representative, and simply relayed his own agenda up the line, blessing decisions already made elsewhere. The president’s daughter Margaret Truman in her memoir of her father’s life, claimed that a meeting occurred in Potsdam at which the president polled the opinions of his leading military men, all or most of whom—according to her account—advised use of the bomb. Later historians in their analysis of Potsdam found such a meeting impossible in the timelines, and no evidence of such a meeting has ever surfaced in any memoirs, diaries, or interviews of the alleged participants—nor has Margaret Truman responded to any of the many enquiries put to her about this issue. Stimson was persuaded to allow others to ghost-write a postwar essay under his name for Harper’s Magazine which reversed all his earlier views and recommendations regarding the bomb, to bring his “new” thinking in line with “Cold War” policy and doctrine. The later memoirs of Stimson, Byrnes, and of Truman, as well as those of others, similarly re-wrote history into a more establishment-friendly tone and outlook—often distorting past realities and sometimes inventing new lies to protect old ones.

Historians and biographers attempting to get at the truth were—and often still are—denied access to private diaries and journals of the major participants, period memoranda and documentation, and official, albeit secret reports, even though many documents and files have been routinely declassified. “Friendly” writers, however, were often granted access. This misuse of information by a supposedly “transparent” democratic government and its representatives who insisted they were hiding nothing, resulted in distortions of history and the misleading of Americans and the world whilst greatly hampering the work of researchers. All of this, of course, is completely inimical to the public’s inherent right to inspect the records of the public’s business.

Post-war policy and America’s “Cold War” place in the world were at stake. Policy-makers wanted Americans to “hang tough” on nuclear weapons, both in order to be ready to use them again and to convince perceived enemies that it had the will to do just that. The perception of an America that did not lie to its people and did not commit war crimes was necessary to sustain.

The responsibility of mass media is likewise subject to question. They had access to all the major political and military figures of the time, yet did not question American policy and actions, instead taking the government line and helped to purvey the mythology surrounding the bomb and its use. Ordinary Americans trusted their government and without any information to the contrary, accepted the myths as truth.

One must wonder about the process of history. Important works on these issues are published, but the readership is surely very small. Some sixty-plus years after these events, the myths stand firmly in the minds of most Americans, while only a relatively small group of scholars and their small readership understand the reality behind them. Meanwhile, everyone is subjected to the mass-message on television and in films wherein a very different—and very false—”establishment” myth-line is purveyed. Another half century from now, or hundreds of years hence, will the myths have been dispelled or will they be just as firmly, or more firmly, established? World War Two is rife with lies and misunderstandings, and entrenched interests wish to keep it that way. A failure to understand the past can surely only be disastrous for the future.

To sum up, the atomic bombings were entirely unnecessary and were in fact acts of genocide that mostly targeted non-combatant civilians resulting in huge numbers of fatalities. To paraphrase F. J. P. Veale’s famous critique of the modern world, the usage of these indiscriminate weapons were far from being a military “advance.” They were rather a “return to barbarism.”

Copyrighted 2010 by Joseph Bishop. All rights reserved.

Notes

| [1] | Gar Alperovitz, The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb: and the Architecture of an American Myth, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1995, p.520. The one-million figure originates from a May 15, 1945 estimate contained in a memorandum sent by former President Hoover to Secretary of War Stimson, thereafter attaining its own life and becoming a popular quote – along with other lower, and also higher, contradictory estimates |

| [2] | Ronald Takaki, Hiroshima: Why America Dropped the Atomic Bomb, Little, Brown and Company, Boston, 1995, p.16 onwards. |

| [3] | No longer seriously disputed by historians and widely documented in countless postwar biographies and histories studying the communist espionage networks within, or closely connected to, the Manhattan Project and their passing of atomic secrets to the Soviet Union, along with treason trials and executions, e.g. that of the Rosenbergs, Klaus Fuchs, et al. Confirmation of these activities was abundantly found in the opening of the former Soviet archives from 1990 onwards. |

| [4] | A useful discussion of the origins of the “unconditional surrender” demand is contained in Takaki, pp.34-37 and elsewhere; a sort of “ad lib” comment by Roosevelt at the 1943 Casablanca conference, it was originally not used more than as a political slogan but came to crystalize within the media and popular consciousness. |

| [5] | Ably discussed in Aperovitz, pp.198-9. |

| [6] | Takaki, op. cit., pp.46-7. Cited are 60,000 fatalities from the blast and approximately 70,000 from radiation etc. by 1950; Nagasaki estimates were 70,000 killed in the initial explosion and another 70,000 from radiation poisoning etc. afterwards. |

| [7] | The most famous being the 1962 Cuban missile crisis. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, vol. 2, no. 1 (spring 2010)

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a