Auschwitz in British Radio Intercepts

The Absence of Clues about “Gas Chambers”

Introduction

Many studies have been dedicated over the decades to the question of what knowledge the Allies and the neutral countries had during the Second World War of alleged exterminations of Jews by the Third Reich in general. What did the Americans know? Or the British? Or the Holy See? What about the International Red Cross?[1] On the “terrible secret” of Auschwitz, however, the literature is rather limited. Except for an excursion by Martin Gilbert (Gilbert 1984), Western historians have only dealt with the question of why the railway lines leading to Auschwitz were not bombed by the Anglo-Americans.[2] Several Polish historians, on the other hand, especially those of the Auschwitz Museum, have thoroughly expatiated (from a perspective to be explained later) on a topic which is also one of the focal points of the present study: the messages sent out of the camp by the Auschwitz Resistance.[3] In this context, the greatest expert is undoubtedly Henryk Świebocki.[4]

The first resistance groups in Auschwitz were formed in the second half of 1940 and multiplied during subsequent years (see Chapter 2.1). From the outside, they were assisted by the Polish resistance movement, which was fragmented into various competing organizations. In addition to sabotaging the German occupational forces, they helped the camp inmates, providing them with food and medicine. The main organizations operating in the Auschwitz region were the Union of Armed Struggle – National Army (Związek Walki Zbrodnie – Armia Krajowa), the Peasants’ Battalions (Bataliony Chłopskie), the Polish Socialist Party (Polska Partia Socjalistyczna), the Polish Workers’ Party (Polska Partia Robotnicza) and the Relief Committee for Concentration Camp Inmates (Komitet Pomoc Więźniom Obozowów Koncentracyjnych). These organizations were in contact with Auschwitz detainees through Polish civilian workers who worked in the camp. From the latter, they received messages and information which they forwarded to the Delegatura, which was the clandestine representation, in occupied Poland, of the Polish Government-in-Exile in London. The Delegatura was organized into twenty offices; the fifth, called “Department of Information and Press” (Departament Infomacji i Prasy), whose code name was “Iskra, 600 PP,” was in charge of collecting, processing and transmitting information from the camp to London.

These aspects have been thoroughly investigated by Polish historians, but the fundamental problem remains: what did the prisoners really know about the alleged extermination of Jews? And what really were their sources?

This study aims to answer these questions. After giving a background on the British intercepting and deciphering of encrypted German radio messages on Auschwitz (Part 1), we will explore and discuss the dubious reports of the camp resistance and of escaped prisoners that they issued until the end of 1944 (Part 2). This allows us to reconstruct the origins and contrasting developments of the story of the Auschwitz gas chambers. The sources, mostly in Polish, were usually examined in the original text.

This is followed in Part 3 by an examination of testimonies made within roughly the first three years after the Soviets’ arrival at Auschwitz, hence until and including 1947 (with some necessary exceptions), which is the year in which the Warsaw trial against the former Auschwitz commander Rudolf Höss and the Krakow trial against the former Auschwitz camp garrison took place. Both trials molded the final version of the gas chamber lore that is by and large still in vogue today.

In Chapter 3.1, I will briefly illustrate Soviet contributions to the creation of the orthodox Auschwitz narrative shortly after they occupied the camp. In the next five chapters, I will analyze early witness testimonies. They are ordered in five categories of decreasing historiographical importance:

- Eyewitness testimonies by Sonderkommando members who claim to have worked inside and around the gas chambers.

- Testimonies by inmates who worked in the crematoria without being members of the Sonderkommando.

- Testimonies of prisoners who claim to have escaped a gassing.

- Testimonies of prisoners who claim to have witnessed the gas chambers accidentally.

- Testimonies of prisoners who claimed to have received information directly from Sonderkommando

Chapter 3.7, “Testimonies of Prisoners Reporting Camp Rumors,” deals with the most important testimonies of this kind recorded in the immediate postwar period (1945-1947). These rumors developed among former Auschwitz inmates who found themselves outside the sphere of Soviet-Polish influence.

The immediate postwar years also saw the first attempts at making these stories look like history rather than fantasy, a topic examined in Part 4, while Part 5, “The Connivance of Orthodox Historians: Deceptions to Hide the Lies,” exposes the vain attempts of some orthodox Holocaust historians to justify patently false witness statements at all costs.

The present study offers a very large collection of primary sources which includes a significant number of reports and testimonies unknown to mainstream Holocaust historiography.

The Absence of Clues about “Gas Chambers”

The British compiled summaries of the messages which also include the section “concentration camps,” among which Auschwitz was listed. The first refers to the period from January 1 to August 15, 1942:[5]

“Strength of Guard: N.C.O.s 108, men unknown. Figure of Prisoners: Jan 6th 9884 Total (presumably, excluding Russian civilians), 191 Jews, 9186 Poles, 2095 Russians (including civilians presumably). Feb. 4th. 10259 Total. 254 Jews, 9506 Poles, 1280 Russians. Again the total presumably excludes Russian civilians and the Russian column includes civilians. March 2nd. 10116. 380 Jews, 9221 Poles, 871 Russians. April 3rd. 10242 Total. 1269 Jews, 8475 Poles, 354 Russians. Here for the first time the Russian column probably contains only prisoners of war. May 5th. 14296. 4010 Jews, 9559 Poles, 182 Russians. June 2nd. 14115 Total. 3466 Jews, 9985 Poles, 153 Russians. July 10th. 16368. 459 Political prisoners, 5998 Jews, 7676 Poles, 153 Russians.

ORANIENBURG’s criticism of their return of April 11 (25/22) can unfortunately not be checked as the relevant figures are missing. A message of 8 May refers to taking over 3128 prisoners from Armaments works in LUBLIN (66/14). A Pole escapes on 13 May (60/18). On 15 May HIMMLER expresses his interest in their tanning experiments (63/17). On 2nd. June AUSCHWITZ complains that the situation is extremely dangerous because the Hungarian replacements for guards given up to Field Units have not arrived (96/39); 90 of the 109 have arrived on 19 June (138/29). On 5 June AUSCHWITZ is told that for political reasons they will not receive 2,000 Jewish workers but on 17 June Jewish transports from Slowakia are announced (104/5; 127/16); their arrival can be seen in the HORHUG reports. A message of June 9th. says that Typhus dominates the camp (113/5): 18 out of 106 cases have died before 15 June (126/4); 22 out of 77 further cases have died before 22nd. June (140/1). On 4 July 100 Schutzhundefuehrer with their dogs are sent to AUSCHWITZ (108/4). On 16 July reference is made to a transport not of Jews but of ‘not interned’ apparently from PARIS (168/41). AUSCHWITZ is told to hand over useless Jewish clothing to the clothing works at Lublin (168/13).”

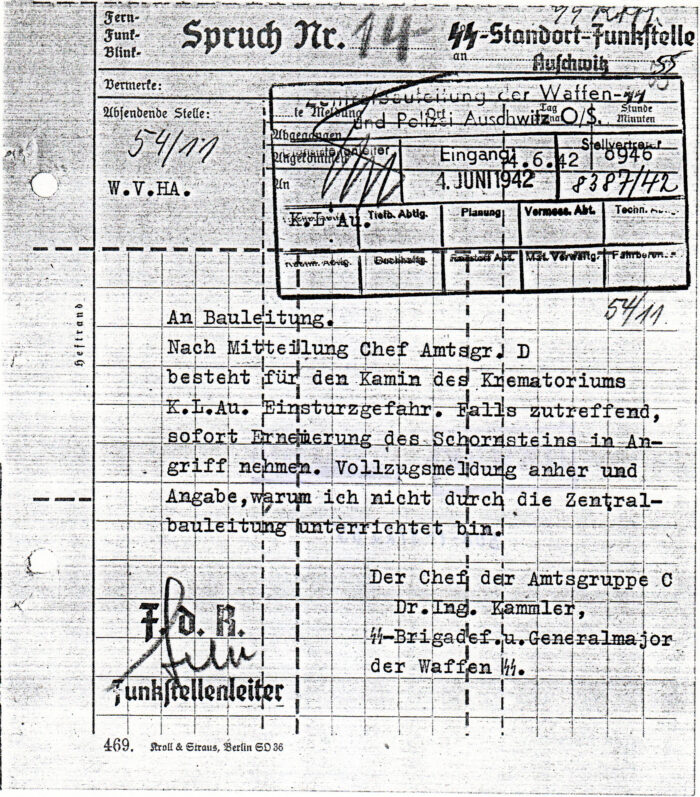

“Oranienburg’s criticism” is the following message by SS Sturmbannführer Arthur Liebehenschel, back then chief of Office D I of the WVHA:[6]

“Reference: your report from April 11, 1942. In your protective-custody-camp report from April 11, 1942, a departure of 1281 Poles is recorded. How is this number made up? On April 11th, 1942, you report a total of 10,282 prisoners in the daily prisoner-strength report, and only 9044 prisoners in the protective-custody-camp report (excluding Soviet POWs). Please clarify the difference immediately (today) by teletype.

sgnd. LIEBEHENSCHEL.”

This shows that the WVHA was examining the reports sent from Auschwitz very carefully.

The next summary covers the time from August 3 to September 25, 1942:[7]

“The August figures follow the prescribed form of 7 columns. Compared with camps hitherto examined, two points stand out 1. that the figures for arrivals and departures[8] are very large every day (see above), 2. that the proportion of Jews is very high and increases from 6241 at the beginning of July to 12011 at the beginning of August. The aggregate of columns 4 to 7 are about 1888 below the total, which includes Russian civilian workers. The movements appear for the most part to be reflected in Columns 4 to 6. In view of the method of reckoning at BUCHENWALD it now appears likely that the large figures for Russians in the January and February returns are all prisoners of war, but that as at BUCHENWALD prisoners of war are not included in the total.”

This is followed by a summary covering the time until October 17, 1942. Some information on Auschwitz is already reported in the section containing general considerations on concentration camps:[9]

“Some light on conditions in Concentration camps is shown by the instruction that a visiting labour commissions not to be shown either ‘special quarters’ (Sonderunterbringung) or, if it can be avoided, ‘prisoners shot when escaping’ (262b/33). […] AUSCHWITZ is being used as a training (and testing?) centre for Volksdeutsche from Hungary and the Balkans (see under SS Div. Prinz Eugen).”

The section addressing Auschwitz directly is very detailed:[10]

“The total figure falls from 22,355 on 1st Sept. to 17,363 on 30th Sept. and to 16,966 on 20th Oct. The number of German political prisoners varies between 496 and 553; the number of Jews falls from 11,837 on 1st Sept. to 6475 on 22nd Sept., the number of Poles falls from a maximum of 8489 on 2nd Sept. to a minimum of 6470 on 19th Oct. No figures for deaths have been given this month and therefore it cannot be said what proportion of the daily departures, which amount to 2395 on 7th Sept., 1429 on 8th Sept., and otherwise vary between 550 and 47, are due to death: it is however known that at least 11 SS men have been taken into hospital on suspicion of typhus during October (253b/3; 261b/3; 267b/4; 259b/13). As about 2,000 men in the total are always unaccounted for, it is difficult to be certain to what categories the arrivals and departures belong. But on 7th Sept. the numbers of political prisoners, Jews and Poles have fallen by 1, 2020, 284, respectively, a net loss of 2305; the net loss in the total column is 2379; therefore it is clear that the majority of the departures are Jews.

A more difficult question arises in October: 400 Volksdeutsche arrived at AUSCHWITZ on the 12th (264b/15), 500 more were to come soon after the 16th (GPD/1124/19), and during the same period transports of Jews were arriving from Holland, Poland, and Czechoslovakia (259b/1). On the 12th 433 arrive, 248 leave; the figure for Jews is up by 185; on the 14th 401 arrive and 95 leave; the figure of the Jews is up by 269; on the 21st 331 arrive, 116 leave, the figure for the Poles is up by 226. It seems therefore clear both that the Volksdeutsche are not included and that the arrivals and departures in AUSCHWITZ are chiefly Jews but sometimes Poles.

VPA[11] figures are also available for September and early October. The VPA figures follow the form of the Stutthof returns i.e. the same as the AUSCHWITZ returns but with an extra column for the total of the preceding day. The camp decreases in size from 16649 on 1 Sept. to 6774 on 20th Sept., although the new arrivals total well over 3000[.] the last column, presumably Russians, remains steady at between 1200 and 1300, the Poles increase from 786 to 1011, the decrease therefore lies between the Germans, the Jews and the unrecorded balance. Internal evidence proves that this camp is near [the city of] AUSCHWITZ; as there is known to be a women’s concentration camp at AUSCHWITZ, where 1525 women died in August (223b/24), it is likely that these figures refer to it.”

Summary No. 4 covers the period from October 18 to November 25, 1942. The section containing general concentration-camp issues mentions a request by the Auschwitz Camp for 490 rifles for “Bosnians,” who were probably the ethnic Germans from that area who had been mentioned in a message of October 29. Changes of the Auschwitz garrison’s staff are given for the time period between October 17 and November 20. The general section also highlights the large transfer of Jews to Auschwitz “for the synthetic rubber works,” the persistence of typhus in this camp, and the transfer of in-patient and partly fit inmates to Dachau (“stationaerkranken and bedingttauglichen”).[12]

On Auschwitz itself we read:[13]

“For the end of October the total continues to rise until on 20 Nov. It reaches 21650, a figure comparable to the figures of early September. The very large arrivals are mostly Jews and the number of Jews rises from 7500 in the middle of October to 10,000 on 20 Nov. 2000 Jews (272b/10; 287b/17, 290b/16; 302b/5) are known to be employed on the Buna Works. 278 prisoners from AUSCHWITZ are employed on the HOLLESCHAU [Golleschau] Portland cement works (274b/30). There is ample evidence that typhus is still rife (see under medical [situation]) and may account for many of the departures. 200 Russian consumptives [tuberculosis patients] arrive from SACHSENHAUSEN on 27 October (279b/36). The women’s camp remains stationary at about 6500 because arrivals balance depatures (G.P.C.C: F3).”

The summary that follows covers the period until December 28, 1942:[14]

“The numbers rise from 20645 on 17 Dec. to 24962 on 15 [sic] Dec; half of these numbers are Jews and large numbers arrive and depart every day. Both AUSCHWITZ and LUBLIN are told to report nos. of escaped Russians, prisoners of war and civilian workers, men and women, on 10 Dec (323b1). The BUNA works return finishes on 2 Dec; over 2500 prisoners are employed there (307b6, 315b8, 21). The figure for the women’s camp (F3) falls from over 7000 in the middle of November to 4764 on 9 Dec. and then rises again to 5231 on 14 Dec. Typhus returns for both camps give 9 women dead in the week ending 24 Nov., 27 men and 36 women dead in the week ending 7 Dec. (307b2; 321b18): A few SS cases are reported (328b3, 32).”

Radio messages to and from the German concentration camps could be decrypted consistently until January 1943. In the last summary covering the time period from December 21, 1942 to January 25, 1943, we read:[15]

“(a) the men’s camp increases from 24962 on 15 Dec. to 28350 on 25 Jan. The Jews decrease from 12360 to 11332; the Poles increase from 8904 to 12646; prisoners in preventive custody jump to 1456 on 20 Jan. 6000 Poles are to be quarantined so that they can be sent to other camps early in February (365b5). The Bunawerk is still employing 2210 men of whom 1100 are on the actual work (364b24). Jewish watchmakers are sent to SACHSENHAUSEN where they are urgently needed (359b25; 356b1).

Typhus cases continue to be reported although strenuous measures have been adopted and 36 cases were found among the new batch of prisoners on 22 Jan. (360b4; 367b6; 366b34; 363b12). (b) The women’s camp also shows an increase in all its columns raising the total from 5231 to 8255 on 25th Jan.”

After this, only a few isolated messages appear, such as this one:[16]

“The Einsatz Reinhardt (see O/S 6,iii.I) is probably referred to again: on 15 Sept. a car is sent from AUSCHWITZ to LITZMANNSTADT to try out the field kitchens for the Aktion REINHARD (237b42).”

Finally, the following message is reported in the summary for the period of February 27 to March 27, 1943:[17]

“On 16 Sept. Himmler ordered the arrest of 5000 Frenchmen who were to be confined in the Concentration Camps at AUSCHWITZ and MAUTHAUSEN.”

Here is the text of the intercepted message:[18]

“Secret! The Rf. SS a. Ch. of Germ. Pol. has ordered the arrest of 5000 Frenchmen, who are to be transfered instantly to Germany into the conc. camps MAUTHAUSEN and AUSCHWITZ. For now, this message is being made… More detailed provisions by the Reich Security Main Office have to be awaited.

Sgnd. LIEBEHENSCHEL.”

These summaries, as will be seen below, reflect in a very superficial and inadequate way the actual content of the intercepts. In particular, those relating to changes in the Auschwitz Camp’s occupancy were intercepted every day, ranging from January 1942 to January 1943, and starting in September 1942 also for the women’s camp.[19]

Lieutenant E.D. Phillips summarized the decrypts regarding “Concentration Camps and Atrocities” as follows:[20]

“Details concerning concentration camps appeared occasionally in decrypts of police [radio] signals, but the fullest information came from returns which were intercepted during 1942 and 1943, until Feb. 43 when the Germans ceased to send them by wireless. The camps concerned were Dachau, Mauthausen with Guben [Gusen], Buchenwald, Flossenbürg, Auschwitz, Hinzert, Niederhagen, Lublin, Stutthof, and Debica; by no means all of the camps, but a fair proportion. Such foundations as Belsen are too recent to have been included in these returns. The regular method was to head each list with a letter of the alphabet, ‘B’ standing for Dachau and subsequent letters except J being allocated to camps in the order given above. ‘A’ no doubt stood for Oranienburg, the administrative centre of the Amtsgruppe [office group] where SS. Brigadefuehrer Gluecks received the returns; hence its own figures as a camp would not be sent over the wireless. The returns as a daily routine were sent in columns without heading to indicate their meaning, but comparisons with other messages made this fairly clear. The columns stood for total strength of prisoners held, arrivals, departures, and various categories of prisoners, such as politicals, Jews, Poles, other Europeans, and Russians, the last sometimes all together, sometimes divided into civilians and prisoners of war. The largest and most fluctuating figures were those for Auschwitz; at the time typhus and spotted fever were mentioned as the main causes of death, with some references to shootings and hangings; there were no references at any time in Special Intelligence to gassing. Auschwitz with a total usually over 20,000 contained the largest number of prisoners, of whom most were Poles and Jews.” (boldface added)

In fact, the letter “J” was also used in the abbreviations for the camps. The abbreviations, according to a scheme titled “GPCC /WWII Concentration Camps Returns,” were the following:[21]

OMA: Oranienburg

OMB: Dachau

OMC: Mauthausen

OMD: Buchenwald

OME: Flossenbürg

OMF: Auschwitz

OMG: Hinzert

OMI: Niederhagen

OMJ: Lublin

OMK: Debica

The Stutthof Camp, as shown by the intercepts, had the initials OML.

The daily variations of the number of inmates incarcerated at Auschwitz are of fundamental importance precisely for the study of the camp’s occupancy, but since this does not fall within the purview of this study, it will not be addressed here.

* * *

The entire book can be accessed through www.HolocaustHandbooks.com; print and eBook copies can be obtained from Armreg Ltd at armreg.co.uk.

Endnotes

| [1] | Among the various published studies, the following may be mentioned as orientation: Laqueur 1980; Wyman 1985; Laqueur/Breitman 1986; Wasserstein 1988; Favez 1988; Ben-Tov 1988. The vexing question of Pope Pius XII’s “silence” was dramatized in Hochhuth 1963. One of the first historians addressing this issue was Friedländer 1964. |

| [2] | One of the first books on this topic is Lichtenstein 1980. |

| [3] | The best work in this regard, though dated, remains Marczewska/Ważniewski 1968. |

| [4] | Świebocki 1995 & 1997; “The Resistance Movement,” in: Długoborski/Piper 2000, Vol. IV. Jarosz 1997 is also useful. I draw the following information from these studies. |

| [5] | TNA, HW 16-65. ZIP/O.S. 1/21.8.42 (Covering the period Jan. 1 – August 15, 1942), p. 18. |

| [6] | TNA, HW 16-17. German Police Decodes Nr. 3 Traffic: 16.4.42. ZIP/GPDD25/5.5.42, No. 22/23/24. WVHA stands for Wirtschaft- und Verwaltungs-Hauptamt, the SS’s Economic and Administrative Main Office. |

| [7] | TNA, HW 16-65. ZIP/OS 2/27.9.42. (Covering the period 3rd Aug. 1942 – 25th Sept. 1942), p. 10. |

| [8] | These are “Zugänge” and “Abgänge,” newly admitted and departed inmates. |

| [9] | TNA, HW 16-65. ZIP/OS3/29.10.42 (Covering the period up to 17th October, 1942), p. 5. |

| [10] | TNA, HW 16-65. ZIP/OS 3/29.10.42, p. 7. |

| [11] | Presumably Variation Partitioning Analysis, the analysis of the daily breakdown of variations in camp occupancy. |

| [12] | TNA, HW 16-65. ZIP/OS 4/27.11.42 (Covering material received between 18th October and 25th November 1942), p. 4. |

| [13] | Ibid., p. 5. |

| [14] | TNA, HW 16-65. ZIP /OS /5 of 28.XII.42 (Covering material received between 25th. November and 25th. December 1942), p. 5. |

| [15] | TNA, HW 16-65. ZIP/ OS/ 6 of 28.I.43 (Covering material received between 21st. December 1942 and 25th January 1943), p. 5. |

| [16] | TNA, HW 16-65. ZIP/OS/7 of 27.II.43 (Covering material received between 25th January and 26th February 1943), p. 4. |

| [17] | TNA, HW 16-65. ZIP/OS/8 of 30.3.43 (Covering material received between 27th February and 27th March 1943), p. 5. |

| [18] | TNA, HW 16-21. German Decodes Nr. 3 Traffic: 16.9.42. ZIP/GPDD 238b/12.3.43, No. 19/20. |

| [19] | TNA, HW 16-10. |

| [20] | E.D. Phillips, pp. 83f. TNA, HW 16/63; underlined words were added in pencil. |

| [21] | TNA HW 16-10. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 2020, Vol. 12, No. 4; excerpt from: Carlo Mattogno, The Making of the Auschwitz Myth: Auschwitz in British Intercepts, Polish Underground Reports and Postwar Testimonies (1941-1947). On the Genesis and Development of the Gas-Chamber Lore, Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield, 2020

Other contributors to this document:

Editor’s comments: