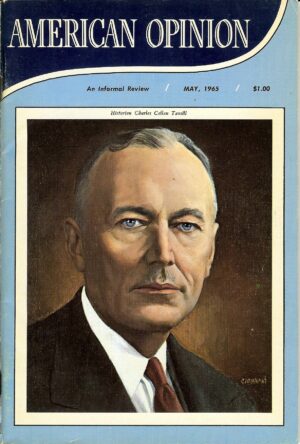

Charles Callan Tansill

Profiles in History

Charles Callan Tansill, one of the foremost American diplomatic historians of the Twentieth Century, was born in Fredericksburg, Texas, on December 9, 1890, the son of Charles and Mary Tansill.[1] Tansill earned his bachelor’s degree from the Catholic University of America in 1912 and his Ph.D. degree from Johns Hopkins University in 1918. At Johns Hopkins he specialized in American diplomatic history, which became his main field of interest throughout his academic life.[2]

Professor Tansill taught American history and American diplomatic relations at several universities including the Catholic University of America (1915–16), American University (1919–37), Fordham University (1939–44), and Georgetown University (1944–57).[3] Tansill wrote several works of diplomatic history, including The Canadian Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 (1922), The Purchase of the Danish West Indies (1932), and Major Issues in Canadian-American Relations (1943).[4] Like many Americans of his day, Tansill was an outspoken isolationist. Controversies surrounded him after he spent 1935 in Germany with financial support from the Carl Schurz Foundation.[5] His pro-German views, which he expressed in many lectures and public forums, ultimately got him dismissed from American University. He was later hired by Fordham and Georgetown.[6]

Today, Tansill is primarily remembered for writings on the causes of both World Wars. For ten years he was technical adviser on diplomatic history to the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. For them he prepared a large work on the causes of World War One, which was never published. Harry Elmer Barnes commented on this work that had it been published, “it would have been ranked with the masterly book of Sidney B. Fay, The Origins of the World War.”[7]

Of his published works, his two most impressive are America Goes to War and Back Door to War: The Roosevelt Foreign Policy, 1933-41. America Goes to War remains the most exhaustive and substantial single volume written from a revisionist perspective on the responsibility for World War One. Columbia University historian Henry Steele Commager wrote of this book in the Yale Review, June 1938 (pp. 855-57):[8]

“It is critical, searching and judicious […] a style that is always vigorous and sometimes brilliant. It is the most valuable contribution to the history of the prewar years in our literature and one of the notable achievements of historical scholarship in this generation.”

Attributing America’s entry into World War One to several factors including lucrative economic ties to bankers and exporters and the pro-British sympathy of President Woodrow Wilson’s advisor Colonel Edward House and Secretary of State Robert Lansing, his massive, carefully documented America Goes to War (1938) won wide acclaim.[9] Tansill condemned the incompetence of House and Lansing and their failure to recognize and act upon American interests. Developing more sharply what had been only an implicit theme of other World War One revisionists, Tansill stressed how the ineptitude and pro-Entente (hence un-American) loyalties of these policymakers had led to the nation’s tragic involvement in a European war. Unlike most other World War One revisionists except Barnes, Tansill did not attribute this failure to the limits to American power and influence.[10] The book’s thesis was well received in Germany. According to Coogan, the German ambassador Hans Dieckhoff sent copies of America Goes to War to the Amerika Institut in Berlin, which in turn distributed it to National Socialist leaders including Hermann Göring.[11]

During the interwar years, like so many of his revisionist colleagues, Tansill opposed US intervention in Europe. Speaking before at the Holy Name Society of St. Joan of Arc Church, he warned:[12]

“If a President of the United States is determined to involve this country in war he is able to do so, despite all the anxious endeavors of a pacific Congress to restrain his war-like ardor.”

From the time of Pearl Harbor through the end of the war, few revisionist titles were written or published. From the late ‘40s and throughout the ‘50s a significant wave of revisionist books were published – most by a circle of academics surrounding Harry Elmer Barnes. Tansill’s work, Back Door to War (1952) was for World War Two from a research standpoint, what America Goes to War was for World War One. Back Door to War remains the definitive revisionist book on American entry into the Second World War.[13] The success of revisionism following the First World War, however, far exceeded its influence after the Second World War. In his Preface to Back Door to War, Tansill commented on the status of revisionism between the two world wars. He wrote:[14]

“The armistice of November 11, 1918, put an end to World War I, but it ushered in a battle of the books that continues to the present day. Responsibility for the outbreak of that conflict was glibly placed by Allied historians upon the shoulders of the statesmen of the Central powers. German historians replied with a flood of books and pamphlets that filled the shelves of many libraries, and the so-called ‘revisionists’ in many lands swelled this rising tide by adding monographs that challenged the Allied war-guilt thesis. While this historical argument was still being vehemently waged, World War II broke out in 1939, and academic attention was shifted to the question of the responsibility for this latest expression of martial madness.”

While revisionist attention may well have shifted to the question of responsibility for World War Two, such investigations failed to overcome the popular accusations that revisionists were merely apologists for Hitler.[15] Back Door to War is a critical history of President Franklin Roosevelt’s 1933–41 foreign policy. In the post-war years it was the major revisionist challenge to the mainstream account of the origins of World War Two.[16] In it Tansill argues that Roosevelt wished to involve the United States in the European War that began in September 1939. When he proved unable to do so directly, he determined to provoke Japan into an attack on American territory. Doing so would involve Japan’s Axis allies in war also, and we would thus enter the war through the “back door.” The strategy of course succeeded, and Tansill maintained that Roosevelt accordingly welcomed Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor.[17]

Tansill argued that since 1900, America’s foreign policy had mainly sought to preserve the British Empire. He blamed America’s involvement in the war partly on Henry Stimson’s belligerence toward Japan since 1932. But mostly Tansill faulted Roosevelt, accusing him of pressuring Neville Chamberlain to fight Hitler; of increasingly involving America in Britain’s war effort; of trying to provoke Hitler into attacking American warships in the Atlantic; and, by escalating economic and diplomatic pressure, of maneuvering the Japanese into attacking Pearl Harbor. Although based on exhaustive research in the State Department archives, Back Door to War received mixed reviews.[18]

Following Back Door to War, Tansill collaborated with several of the best-known World War Two revisionists on Harry Elmer Barnes’s anthology, Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace (1953). Tansill contributed two articles, “The United States and the Road to War in Europe” and “Japanese-American Relations: 1921-1941; The Pacific Back Road to War” that continued his argument from Back Door to War. His work was bolstered by Barnes, Frederic Sanborn, George Morgenstern, Percy Greaves, Jr., William Henry Chamberlin and others.

Besides his revisionist circle of friends, Tansill maintained close associations with several figures of the far right. He was close to both George Sylvester Viereck and H. Keith Thompson.[19] Thompson commented of Tansill:[20]

“My Georgetown friend was Charles Callan Tansill, Prof. of History and author of many books and articles. […] Tansill was a member of the Viereck circle. I met him there frequently, visited with him in Washington, and did some favors for him in the publishing world. He was under constant pressure at Georgetown because of his views on segregation […].”

After retiring from Georgetown in 1958, Tansill began writing articles attacking integration for the John Birch Society’s American Opinion.[21] Tansill was also a member of the International Association for the Advancement of Ethnology and Eugenics’s (IAAEE) Executive Committee. The IAAEE was a prominent group in the promotion of eugenics and segregation, and the first publisher of Mankind Quarterly.[22] Tansill was also an honorary board member of Mankind Quarterly.[23]

Tansill’s associations, as well perhaps as the strength of his arguments have resulted in his condemnation by outspoken members of the anti-revisionist crowd. Deborah Lipstadt in her anti-revisionist screed Denying the Holocaust wrote:[24]

“Tansill set out a number of arguments that would become essential elements of Holocaust denial.”

While Tansill did not comment on the Holocaust in his writing, he is subject to the ad hominem attack and damning label of “denier” because he dared to question the accepted version of responsibility for the Second World War.

Charles Callan Tansill was a great historian who sought to discover the truth of the World’s greatest conflicts. When his discoveries varied from the official story, he refused to keep quiet. Despite the impact on his career and his reputation, Tansill remained an outspoken voice for revisionist history. Charles Tansill died in Washington D.C. on November 12, 1964.[25] In a memorial published in 1965, Tansill was remembered as follows:[26]

“Charles Callan Tansill was devoted to his religion and the devotion was reflected in his logic and philosophy and his tireless pursuit of Truth.”

Notes:

| [1] | Online: http://records.ancestry.com/Charles_C_Tansill_records.ashx?pid=101221649 |

| [2] | Harry Elmer Barnes, Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace (Caldwell, Idaho, The Caxton Printers, 1953), p. 80. |

| [3] | Online: http://www.firstprinciplesjournal.com/articles.aspx?article=663&theme=home&loc=b |

| [4] | Ibid. |

| [5] | Kevin Coogan, Dreamer of the Day: Francis Parker Yockey and the Postwar Fascist International (Brooklyn, Autonomedia, 1999), p. 471. Named after Carl Schurz, a German-American patriot and US Senator, the Carl Schurz Foundation was founded in 1930 to foster relations between the US and German-speaking nations. Shortly after the Foundation was founded it established the Oberlander Trust to sponsor visits by American scholars to German-speaking countries for study and research purposes. |

| [6] | Coogan, op. cit., pp. 471-72. |

| [7] | Barnes, op. cit., p. 80. Fay’s work was a major revisionist breakthrough following World War One. It largely changed the way people looked at the causes of the war by rejecting the idea that Germany was primarily responsible. |

| [8] | Barnes, op. cit., p. 80. |

| [9] | Online: http://www.firstprinciplesjournal.com/articles.aspx?article=663&theme=home&loc=b |

| [10] | Online: http://www.americanforeignrelations.com/O-W/Revisionism-World-war-i-revisionism.html#b |

| [11] | Coogan, op. cit., p. 477 note 39. |

| [12] | Warren I. Cohen, The American Revisionists: The Lessons of Intervention in World War I (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1967), p. 220. |

| [13] | Barnes, op. cit., p. 80. |

| [14] | Charles Tansill, Back Door to War: Roosevelt Foreign Policy 1933-1941 (Chicago, Henry Regnery, 1952), p. vii. |

| [15] | For more on this point see Robert LeFevre, “On the Other Hand,” Rampart Journal of Individualist Thought Vol. 2, No. 1, Spring 1966. LeFevre comments: “A case in point is the revisionist approach to World War II. In highlighting guilty actions leading to war, and the complicity and duplicity of men in the United States, the United Kingdom, and elsewhere, revisionists have made Hitler and the Axis powers appear more innocent than the popular view holds them to be. Thus, it has been said of revisionists that they are apologists for Hitler, pro-Nazi, and actually appear to justify the war.” |

| [16] | Online: http://www.firstprinciplesjournal.com/articles.aspx?article=663&theme=home&loc=b |

| [17] | Online: http://mises.org/document/3130/Back-Door-to-War-The-Roosevelt-Foreign-Policy-19331941 |

| [18] | Online: http://www.firstprinciplesjournal.com/articles.aspx?article=663&theme=home&loc=b |

| [19] | George S. Viereck is best remembered for having given a speech to twenty thousand “Friends of the New Germany” at New York’s Madison Square Garden in 1934, in which he compared Hitler to Franklin Roosevelt and told his audience to sympathize with National Socialism. In 1941, he was indicted in the U.S. for a violation of the Foreign Agents Registration Act when he set up a publishing house, Flanders Hall. He was convicted in 1942 for this failure to register with the US Department of State as a “Nazi agent.” He was imprisoned from 1942 to 1947. Harold Keith Thompson was a Special Agent of the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) Overseas Intelligence Unit during World War Two. Thompson was friends with many key far-right figures in the post-war years including Otto Skorzeny and General Otto Ernst Remer. |

| [20] | Coogan, op. cit., p. 472. Thompson apparently made this comment in a personal communication to Kevin Coogan on 31 October 1994. |

| [21] | Coogan, op. cit., p. 472. The John Birch Society is a political advocacy group that was established in 1958. It was led by Robert Welch Jr. and espoused a staunchly anti-communist position. It was named after John Birch, a US intelligence officer who was killed by communists in China in August 1945. He was considered the first victim of the Cold War. |

| [22] | Online: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Association_for_the_Advancement_of_Ethnology_and_Eugenics |

| [23] | Coogan, op. cit., p. 485. |

| [24] | Deborah Lipstadt, Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory (New York, Plume, 1994), p. 40. Lipstadt, a professor of Jewish and Holocaust Studies at Emory University also calls Back Door to War “the most extreme revisionist account of America’s entry into World War II.” |

| [25] | Francis X. Gannon, “Charles Callan Tansill,” American Opinion, Vol. 8, No. 5, May 1965, p. 97. |

| [26] | Ibid. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 5(3) (2013)

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a