Filip Müller’s False Testimony, Part 2

The following article was taken, with generous permission from Castle Hill Publishers, from Carlo Mattogno’s recently published study Sonderkommando Auschwitz I: Nine Eyewitness Testimonies Analyzed (Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield, 2021; see the book announcement in Issue No. 2 of this volume of Inconvenient History). In this book, it features as Sections 4 and 5 of Part 1. The other sections of Part 1 are included in the previous and the next issue of Inconvenient History. References to monographs in the text and in footnotes point to entries in the bibliography, which is not included in this excerpt. It can be consulted in the eBook edition of this book that is freely accessible at www.HolocaustHandbooks.com. Print and eBook versions of this book are available from Armreg at armreg.co.uk/.

4. Plagiarized History of Birkenau: Miklós Nyiszli

4.1. “Dayan’s Speech”

As mentioned earlier, the primary source of Müller’s Holocaust statements regarding Birkenau is Miklós Nyiszli. The memoirs of this formidable impostor (see Mattogno 2020a) appeared in Hungarian in 1946 with the title “I was Dr. Mengele ‘s Anatomist at the Auschwitz Crematorium” (“Dr. Mengele boncolóorvosa voltam az Auschwitz-i krematóriumban”). The first German translation was published in installments in 1961 in the Munich magazine Quick, Nos. 3-11, under the title “Auschwitz. Diary of a Camp Doctor” (“Auschwitz. Tagebuch eines Lagerarztes”). And it was after 1961, in his deposition at the Frankfurt Trial, that Müller first mentioned Nyiszli, but at that time he did not yet know how to use the testimony of this Hungarian physician.

In his book, Müller drew profusely from the afore-mentioned translation, up to direct plagiarism. The most brazen, almost verbatim plagiarism concerns the “the speech of the Dajan” that I will analyze first. I begin with this, because this plagiarism is so evident that it is impossible to mistake the further plagiarisms I will report subsequently.

To prevent the objection that Müller, in 1979, hence 35 years after the claimed event, remembered the exact words allegedly uttered in late 1944 by the “Dajan,” and remembered them exactly the same way as Nyiszli did in 1946, namely that both had personally witnessed the same real event, it is illuminating to outline the general context in which the two witnesses insert the speech in question, starting with Nyiszli:[1]

“In the early morning hours of November 17, 1944, an SS NCO opens the door to my room and confidentially informs me that by order of the Reichsführer the killing of people in any fashion within the grounds of the K.Z. has been strictly prohibited. […]

My watch showed two p.m. It is after lunch and I am looking apathetically out our window at the darkly swirling clouds of snow when a loud shout disturbs the silence of the furnace-hall corridor. ‘Alle antreten!’ [‘Everyone fall in!’ German in text] sounds the order. We hear it two times a day, morning and evening, for the customary roll call, but in the afternoon it is of ominous significance. ‘Alle antreten!’ it sounds again, still sharper, still more impatient.

Now heavy footsteps resound at the door to our room; an SS man opens it and shouts: ‘Antreten!’ Here’s trouble! We head for the courtyard. We step out into a large circle of SS guards; our comrades are already standing there. There is not the least surprise here, not the least noise. The SS units stand silently with machine pistols trained on us and wait patiently until everyone is in the group. I look around. The young fir trees of the little grove stand unmoving, covered in white. Everything is so silent!

A few minutes later we are ordered to face left and we start off between the close-ranked lines of armed guards. Leaving the crematorium courtyard, our escort does not lead us onto the road, but rather across the road, in the direction of Crematorium II [=III] standing opposite. Sure enough, we advance through its courtyard. We know now that this is our final journey. We are all herded into the crematorium’s furnace hall. Not a single SS guard remains inside. They stand around the building, at the doors and windows, with machine pistols ready for firing. The doors are locked; heavy iron grills cover the windows. There is no way out here. The comrades from Crematorium II are here as well! A few minutes later the ones from number IV are brought in. Four hundred and sixty men stand together and wait for death; only the method of execution still constitutes a matter for conjecture. Here there are specialists who know all of the death-bringing methods of the SS. The gas chamber? That would be impossible to carry out smoothly with the Sonderkommando! Shooting? That is a method that is scarcely feasible here, inside!

The most likely scenario is that they will blow us up together with the building in the interest of achieving two goals at once. That would be genuine SS method, or perhaps we will receive a few phosphorus grenades through the window. […]

In mute silence, wordlessly – if someone says something to his companion, he does so in a whisper – the Kommando men hunker down wherever they have found places on the concrete of the furnace hall floor. Suddenly the silence is broken: one of our comrades, a black-haired, tall, slim man wearing glasses, about thirty years of age, leaps up from his place and in a ringing voice, so that all can hear, begins to speak. He is a ‘dájen,’[2] which is a sort of auxiliary priest in a little Jewish community in Poland. He is an autodidact with a great store of religious and worldly knowledge at his command. He is the ascetic of the Sonderkommando, a man who, in order to abide by the dietary prescriptions of his faith, eats nothing from the bountiful kitchen of the Sonderkommando but bread, margarine and onions. His assignment was to have been stoker on a cremation furnace, but as he is a man of fanatic faith I have arranged with Oberscharführer Mussfeld that he should receive an exemption from this horrible work. […]

I had no other arguments. The Ober accepted them, and at my suggestion the man was sent to the so-called Canada rubbish heap burning in the courtyard of Crematorium II (=III). One should know of this rubbish heap that they bring here all the personal effects and spoiled food, as well as identification papers, diplomas, documents concerning military honors, passports, marriage certificates, prayer books, phylacteries, and Torah scrolls which the transports sent to the gas chambers brought with them from home but which were condemned to be burned as useless items by the SS’s evaluative criteria.

The Canada rubbish heap was a constantly burning mound; in this place hundreds of thousands of photographs of married couples, elderly parents, attractive children and beautiful girls burned in the company of thousands of prayer books. […]

Here the ‘Dayan’ worked, or rather did not work but merely watched the fire, but he was dissatisfied even with this when I inquired how he was doing. It did not comport with his religious ideas that he should collaborate in the burning of prayer books, phylacteries, prayer shawls and Torah scrolls either. I sympathized with him, but I had no means to provide him with an easier job. In the end we were in a K.Z. and Sonderkommando men in a crematorium!

This was the ‘Dayan’ who began to speak.”

This is followed by the text of the claimed speech, which I will address later.

“The heavy doors spring open. Oberscharführer Steinberg enters the hall, accompanied by two guards with machine pistols. ‘Aerzte heraus!’ he shouts in an imperious voice. I leave the hall with my two doctor colleagues and my laboratory assistant. Steinberg and the two SS soldiers stop with us on the road between the two crematoria. The Ober gives me some sheets of paper covered with numbers which he has been holding in his hands until now and tells me to find my number and cross it out. In my hands is a list of the tattoo numbers of Sonderkommando members. I take out my fountain pen; after a quick search I find and cross out my number. When I have done this, he tells me to cross out my companions’ numbers as well! This too is done. He accompanies us to the gate of Crematorium I. He orders us to retire to our rooms and not to move from there! We do so.

The next morning a column made up of five trucks arrives in the crematorium courtyard. They dump out corpses from themselves. The corpses of the Sonderkommando. A newly constituted group of thirty carries the victims into the cremation hall. They are laid out in front of the furnaces. Horrible burn lesions cover their bodies. Their faces are burned beyond recognition, their burned and tattered clothes make identification impossible. Even the numbers burned onto their arms are illegible for the most part.

After death by gas, death at the pyres, death by chloroform injection to the heart, the shot to the back of the neck, death in the flames of the pyres and death by phosphorus grenade, this is the seventh type of death I have met with.

They took my poor comrades to a nearby forest during the night and did away with them with flamethrowers.

If the four of us survived, the underlying motive still was not the sparing of our lives, but rather just the necessity of our survival for as long as our positions needed filling. It was neither joy nor even relief this time, merely respite, which Dr. Mengele afforded us in leaving us alive.”

And here is Müller’s respective narration (Müller 1979b, p. 161):

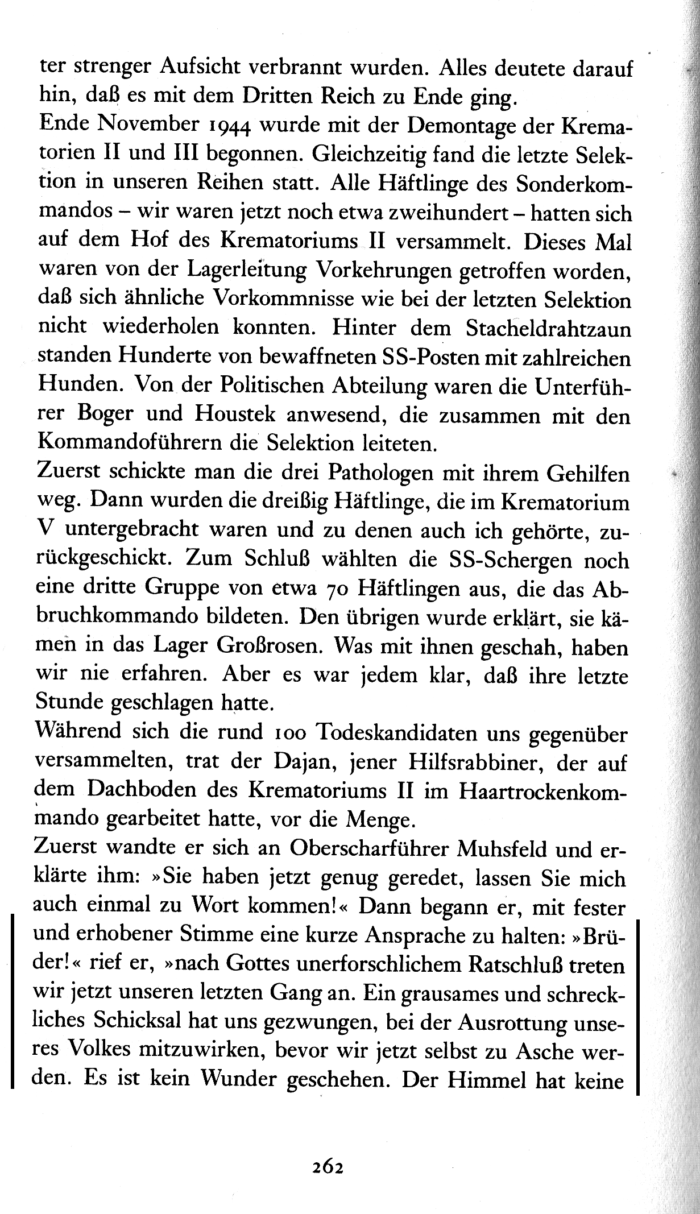

“Towards the end of November 1944 the dismantling of crematoria 2 and 3 began. At the same time there was a final selection among members of the Sonderkommando. All prisoners in the team were lined up in the yard of crematorium 2. This time the camp authorities had taken precautions to prevent a repetition of events during the previous selection. Hundreds of armed SS guards with a large number of dogs stood behind the barbed-wire fence. The political department was represented by Unterführers Boger and Hustek who, together with the Kommandoführers were in charge of the selection.

For a start, the three pathologists and their assistants were sent to one side and after them the thirty prisoners, including myself, billeted in crematorium 5. Finally the SS chose a third group of some seventy prisoners who were to form the demolition team. The rest were told they would be transferred to camp Grossrosen. What happened to them we never learned, but we all realized that their time had come.

Suddenly from out of the ranks of doomed prisoners stepped the young Rabbinical student who had worked [German original: in the attic of Crematorium II; 1979a, p. 262] in the hair-drying team. He turned to Oberscharführer Muhsfeld and with sublime courage told him to be quiet. Then he began to speak to the crowd:”

This is then followed by the text of the claimed speech itself.

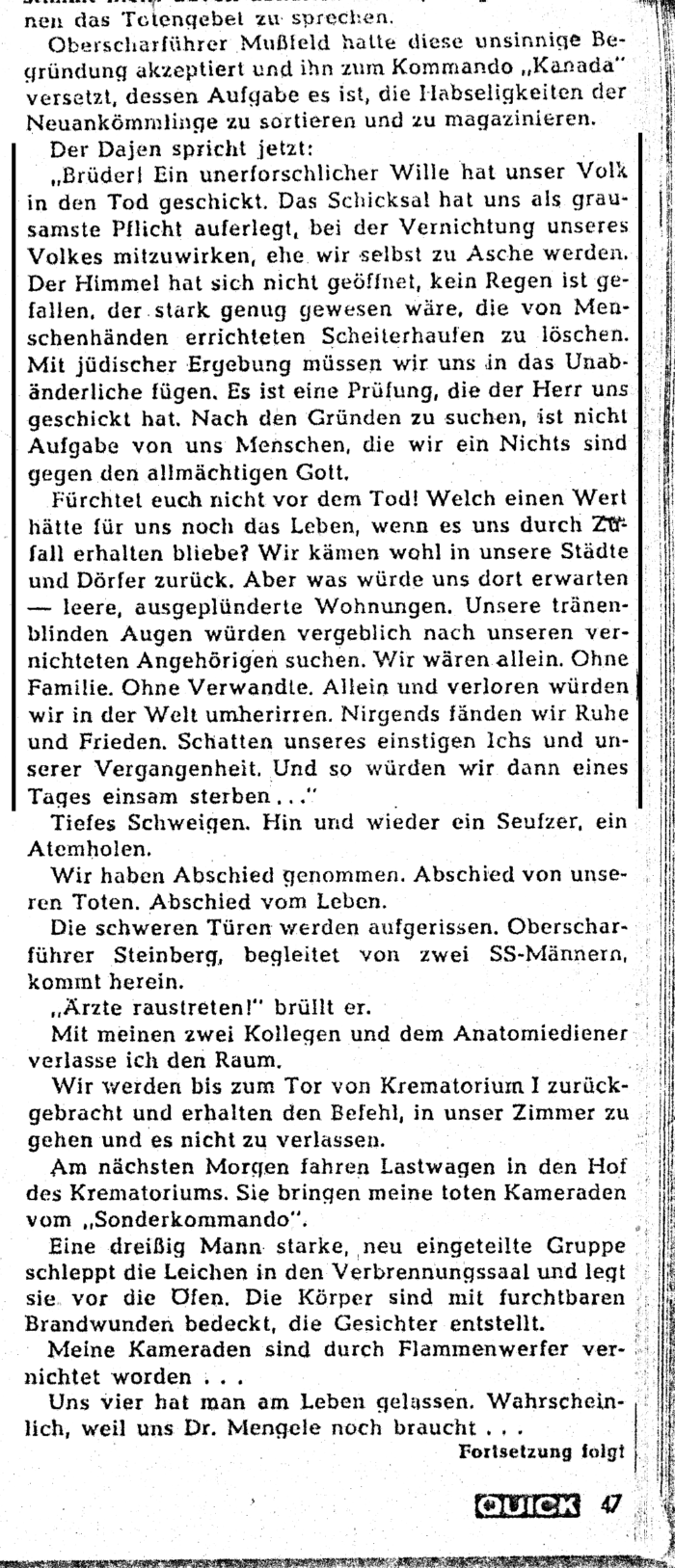

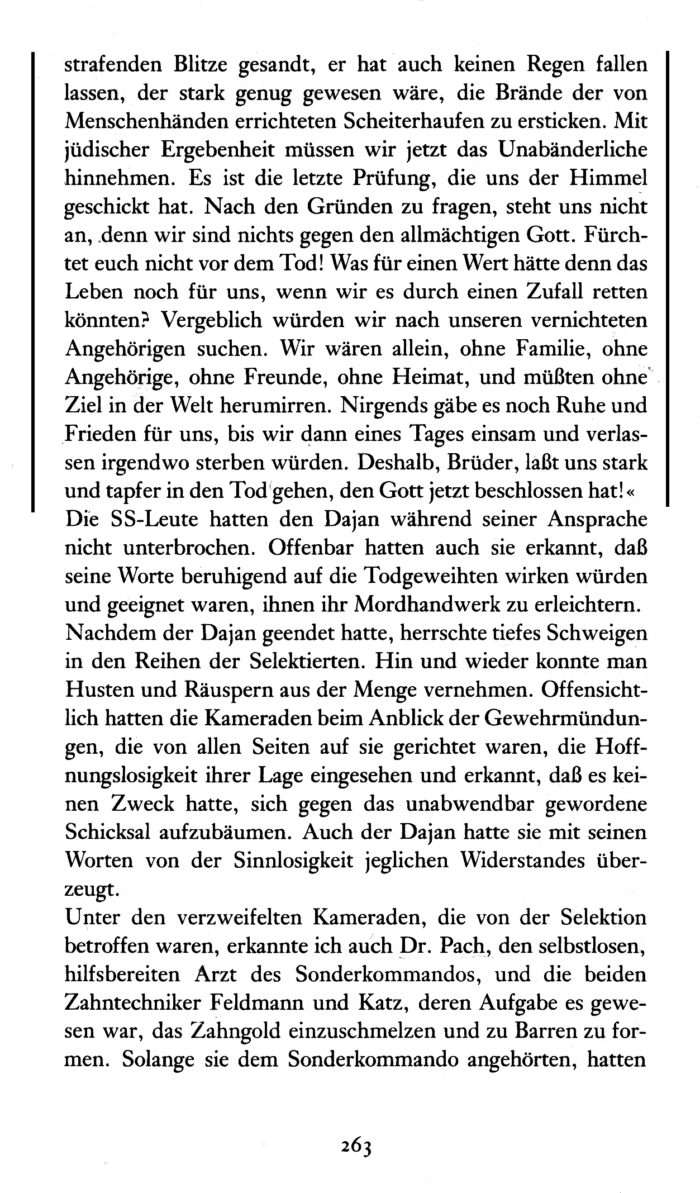

In the following table I compare Nyiszli ‘s text of this speech according to the translation published by Quick (to the left)[3] with Müller’s text (to the right):[4]

| “Brüder! | “‘Brüder!’ rief er, |

| Ein unerforschlicher Wille hat unser Volk in den Tod geschickt. | ‘nach Gottes unerforschlichem Ratschluss treten wir jetzt unseren letzten Gang ein. |

| Das Schicksal hat uns als grausamste Pflicht auferlegt, bei der Vernichtung unseres Volkes mitzuwirken, ehe wir selbst zu Asche werden. | Ein grausames und schreckliches Schicksal hat uns gezwungen, bei der Ausrottung unseres Volkes mitzuwirken, bevor wir jetzt selbst zu Asche werden. |

| Der Himmel hat sich nicht geöffnet, kein Regen ist gefallen, der stark genug gewesen wäre, die von Menschenhänden errichteten Scheiterhaufen zu löschen. | Der Himmel hat keine strafende Blitze gesandt, er hat auch keinen Regen fallen lassen, der stark genug gewesen wäre, die Brände der von Menschenhänden errichteten Scheiterhaufen zu ersticken. |

| Mit jüdischer Ergebung müssen wir uns in das Unabänderliche fügen. | Mit jüdischer Ergebenheit müssen wir jetzt das Unabänderliche hinnehmen. |

| Es ist eine Prüfung, die der Herr uns geschickt hat. | Es ist die letzte Prüfung, die uns der Himmel geschickt hat. |

| Nach den Gründen zu suchen, ist nicht Aufgabe von uns Menschen, die wir ein Nichts sind gegen den allmächtigen Gott. | Nach den Gründen zu fragen, steht uns nicht an, denn wir sind nichts gegen den allmächtigen Gott. |

| Fürchtet euch nicht vor dem Tod! | Fürchtet euch nicht vor dem Tod! |

| Welch ein Wert hätte für uns noch das Leben, wenn es uns durch Zufall erhalten bliebe? | Was für ein Wert hätte denn das Leben noch für uns, wenn wir es durch einen Zufall retten könnten? |

| Wir kämen wohl in unsere Städte und Dörfer zurück. Aber was würde uns dort erwarten – leere, ausgeplünderte Wohnungen. Unsere tränenblinden Augen würden vergeblich nach unseren vernichteten Angehörigen suchen. | Vergeblich würden wir nach unseren vernichteten Angehörigen suchen. |

| Wir wären allein. Ohne Familie. Ohne Verwandte. Allein und verloren würden wir in der Welt umherirren. | Wir wären allein, ohne Familie, ohne Angehörige, ohne Freunde, ohne Heimat, und müssten ohne Ziel in der Welt herumrirren. |

| Nirgends fänden wir Ruhe und Frieden. Schatten unseres einstigen Ichs und unserer Vergangenheit. | Nirgends gäbe es noch Ruhe und Frieden für uns, |

| Und so würden wir dann eines Tages einsam sterben…” | bis wir dann eines Tages einsam und verlassen irgendwo sterben würden. |

| Deshalb, Brüder, lasst uns stark und tapfer in den Tod gehen, den Gott jetzt beschlossen hat.’” |

This at-times-verbatim plagiarism requires an explanation. Müller was a Slovak native speaker, but, as I noted above, he spoke German, albeit with difficulty. He certainly wrote the draft of his book in Slovak, and the Archive of the Yad Vashem Institute in Jerusalem holds about seventy pages of it.[5] His book, however, appeared directly in German; it is not a translation. In fact, no previous Slovak edition exists. It is therefore clear that it was Müller himself who translated the Slovak draft into German (with the help of Helmut Freitag, who carried out the German reworking of the text) and it was again Müller who transcribed into the German draft the aforementioned passages he copied directly from Nyiszli ‘s Quick article.

The plagiarism is even more pronounced than it might appear from this comparison, because it mostly involves the other words not directly copied, which Müller replaced with synonyms or paraphrased, as is clearly evident from the comparison of the two translations:

| “Brothers! | “‘Brothers!’ he cried, |

| An unfathomable will has sent our people to their death. | ‘according to God’s unfathomable counsel, we are now entering our final course. |

| Fate has given burdened us with the cruelest duty to participate in the annihilation of our people before we ourselves turn into ashes. | A cruel and terrible fate has forced us to participate in the extermination of our people before we ourselves turn into ashes. |

| The sky has not opened, no rain has fallen that would have been strong enough to extinguish the pyres made by human hands. | Heaven did not send punitive lightning, it did not let any rain fall either that would have been strong enough to stifle the fires of the pyres made by human hands. |

| With Jewish submission, we must submit to the immutable. | With Jewish submissiveness we must now accept the immutable. |

| It is an ordeal the Lord has sent us. | It is the last ordeal Heaven has sent us. |

| It is not up to us humans to look for the reasons, since we are nothing compared to Almighty God. | It is not up to us to ask for the reasons, for we are nothing compared to Almighty God. |

| Do not be afraid of death! | Do not be afraid of death! |

| For what value would life still have for us if it were preserved by chance? | What value would life still have for us if we could save it by chance? |

| We would probably come back to our cities and villages. But what would await us there – empty, looted dwellings. Our tear-blind eyes would search in vain for our annihilated relatives. | We would search in vain for our annihilated relatives. |

| We would be alone. Without family. Without relatives. Alone and lost we would roam about the world. | We would be alone, without family, without relatives, without friends, without a home, and would have to roam about the world aimlessly. |

| Nowhere would we find peace and quiet. Shadows of our former selves and our past. | Nowhere would there be peace and quiet for us, |

| And so one day we would die lonely…” | until one day we would die lonely and abandoned somewhere. |

| Therefore, brothers, let us go strong and valiant to the death God has now ordained.’” |

Even the claim that the “Dayan” “ate almost nothing but bread, margarine and onions” (Müller 1979b, p. 66; “aß er fast nur Brot, Margarine und Zwiebeln”; 1979a, p. 104)” was copied almost verbatim from Nyiszli: “he nourished himself… only with bread, margarine and onions” (“hat er sich […] nur von Brot, Margarine und Zwiebeln ernährt”; Nyiszli 1961, No. 10, p. 47).

Nyiszli believed that the Effektenlager, the Birkenau warehouse sector consisting of 30 barracks, called “Kanada” in the camp slang, was a burning rubbish heap that was in the courtyard of Crematorium III! Müller was helped to avoid such a blunder, because the translator of the Quick article intervened drastically to correct it by radically rewriting the text: where the original text, in correct translation, says (Mattogno 2020a, p. 116):

“I had no other arguments. The Ober[scharführer Mussfeld] accepted them, and at my suggestion the man [the Dajan] was sent to the so-called Canada rubbish heap burning in the courtyard of Crematorium II,”

the mendacious German mistranslation reads (Nyiszli 1961, No. 10, p. 47):

“Oberscharführer Mussfeld had accepted this nonsensical reason and transferred him to the ‘Canada’ unit, whose task it is to sort and store the belongings of the newcomers.”

He saved himself by making up the story that the “Dayan” had worked “in the attic of Crematorium II in the hair-drying team,” yet by so doing, he introduced an irreducible contradiction to Nyiszli ‘s story.

What irrefutably confirms the plagiarism is the context in which the speech was delivered according to the two witnesses: for Nyiszli, this happened in the furnace room of Crematorium III (according to today’s numbering), in front of 460 inmates of the “Sonderkommando”; for Müller, it took place in the courtyard of Crematorium II in front of about 200 inmates of the “Sonderkommando.” For Nyiszli, all the inmates were selected and killed except himself and his three coworkers, namely the physicians Dénes Görög and Józef Körner, as well as the laboratory assistant Adolf Fischer, who were therefore the only survivors of the selection. For Müller, however, there were 100 survivors! For Nyiszli, who never mentions Müller, Müller would have been among those selected, hence would have been killed right then and there. This explains why Müller kept quiet about Nyiszli. As mentioned earlier, he mentioned Nyiszli for the first time during the 98th hearing in the Frankfurt Trial (Fritz Bauer…, pp. 20696-20698):

“1944, during the Hungarian transports, there were two Hungarian physicians, pathologists, in one room in Crematorium I [=II]. One of them, if I remember correctly, was called Doctor Nyiszli, a strong man. They had conducted experiments. And Doctor Mengele joined them very often. These two inmates were then taken to Crematorium IV [=V], where they were in the room next to the chimney – that was the room that connected the cremation room with the undressing room… There, in this room, another man who wasn’t a doctor worked with these two Hungarian doctors. And he came from Theresienstadt. I personally saw that they had put a hunchbacked person into a barrel. They put various salts and acids in it in order to obtain his skeleton.”

In the statements cited earlier, Müller limited himself to misrepresenting some data in Nyiszli ‘s story: The “pathologists” who were transferred to Crematorium V were not two, but, as I have clarified above, three, plus a laboratory assistant, and these, I repeat, were the only survivors of the “Sonderkommando.” They had never conducted any experiments in Crematorium II, but only autopsies. The presence of an assistant from Theresienstadt is Müller’s invention, and the anecdote of the hunchback is imaginatively taken from Nyiszli’s narration. Nyiszli wrote that a father and son arrived with a transport from the Lodz Ghetto, the father hunchbacked, the son with a deformed foot, so they attracted Dr. Mengele ‘s attention, who had them killed in order to exhibit their skeletons as proof of the degeneration of the Jewish race (a theory invented and attributed to Mengele by Nyiszli). Nyiszli boiled the two corpses in two iron barrels, but it all happened in the courtyard of Crematorium II (Mattogno 2020a, pp. 106-109), yet for Müller, inside Crematorium V!

Nyiszli ‘s testimony was evidently too embarrassing for Müller, so the Hungarian doctor disappears in his book; he is never mentioned.

Nyiszli, in his memoirs, claimed to have been the only physician and at the same time the only inmate of the “Sonderkommando” who had survived: all the others had been killed or had died (his three collaborators). For Müller, on the other hand, there were only two doctors from the “Sonderkommando,” Dr. Pach and Dr. Bendel. According to Müller, “a sort of consulting room linked to a small hospital” had been set up in Block 13 of Camp Sector BIId, where the “Sonderkommando” was lodged.

“In charge of this hospital was Dr Jacques Pach, at that time the only doctor in the Sonderkommando. […] It was in the spring of 1943 that Jacques Pach was appointed as doctor in the Sonderkommando.” (Müller 1979b, p. 63)

Many pages later, Müller explains that it had become necessary “to establish a small ward for prisoners requiring in-patient treatment,” and he adds:

“Once Dr Pach ‘s ward for in-patients had been set up the treatment of Sonderkommando out-patients was taken over by Dr Bendel.” (Ibid., p. 148)

Previously, up to and including his Frankfurt testimony, Müller knew nothing of Dr. Pach, and he undoubtedly took this information from Henryk Tauber ‘s statement of May 24, 1945, of which he probably had only second-hand knowledge (Mattogno 2020a, pp. 372f.). The same is true for Dr. Charles Sigismund Bendel, a perjurious professional witness who between 1945 and 1948 gave as many as six false testimonies. He declared that he entered the “Sonderkommando” as a physician on June 2, 1944, and remained there until January 17, 1945 (see ibid., Chapter 4.2., pp. 304-333). Due to these six-and-a-half months of allegedly living together, Müller should have known Bendel perfectly well, and yet, the only reference to Bendel in his book is the one just quoted. It is therefore clear that he had never met him, and had simply read his name in some book in his library. Not knowing what to write about him, he resorted to the old story of “pathologists” inspired by Nyiszli ‘s book. Just as suddenly, “two Hungarian doctors, Dr. Peter and Dr. Havas “ enter the scene out of nowhere and without any further explanation (Müller 1979a, p. 248). The sanitized English translation omits their names altogether (1979b, p. 154). Further on, when writing about the selection at the end of November 1944, Müller wrote, as quoted earlier: “For a start, the three pathologists and their assistants were sent to one side […]”. Finally, in reference to Crematorium V, he states (German edition, 1979a, p. 264):

“Here, under the direction of Dr. Mengele, who was assisted by three inmate physicians and the autopsy assistant Fischer, carried out corpse autopsies, which were part of the pseudo-medical experiments with which he was concerned.”

The sanitized English translation omits all three inmate physicians and Fischer ‘s name:

“In the same building behind a wooden partition was the dissecting room where Dr Mengele and his assistants continued with their pseudo-medical experiments.” (1979b, p. 162)

With various contortions, Müller also plagiarized from Nyiszli the story of the transfer of the dissection room to Crematorium V (Nyiszli 1961, No. 11, p. 50):

“Everything is packed up in the dissecting room and laboratory. We only take the marble slab from the autopsy table. After a few hours, we are finished with the move and have set up both the autopsy room and the laboratory in Crematorium IV [= V].”

However, according to this account, the four inmates mentioned by Müller were the three doctors Nyiszli, Görög and Körner and the laboratory attendant Fischer. At the Frankfurt trial, as seen above, Müller had spoken of “two Hungarian physicians, pathologists,” one of whom, if he remembered correctly, “was called Doctor Nyiszli.”

As noted earlier, Müller introduces Dr. Bendel in his book with just a few lines as a 1944 “Sonderkommando” physician, who then disappears completely. In his place, suddenly “two Hungarian doctors, Dr. Peter and Dr. Havas,” appear from a brief glimpse, who are supposed to be the two previous “pathologists,” although one of them was Nyiszli. Finally, by some miraculous doubling, these two inmate physicians turn into four, one of whom was Adolf Fischer, so the other three must have been Nyiszli, Görög and Körner.

Plagiarisms, and the need to hide them, ensnared Müller in a series of contradictions with no way out. I say plagiarisms, because what I pointed out above, while being the most striking example, is not the only one. Another one in the context outlined above is his reference to “pseudo-medical experiments” in the previous quote. It is obvious that Müller had no competence to judge the medical value of any experiments, let alone those allegedly conducted in his absence. In fact, he merely appropriated in two words Nyiszli ‘s invective on the allegedly pseudo-scientific nature which he ascribed to Dr. Mengele ‘s research (Mattogno 2020a, p. 109).

4.2. The Gassing Scene

The most-egregious plagiarism, which alone undermines Müller’s credibility (assuming that we can still speak of any credibility at this point), is that concerning the alleged gassing scene. Here, the plagiarism is much more complex. Müller has broken down Nyiszli ‘s related story into sections and recomposed it by changing their sequence and embroidering it with his own interpolations or by taking motifs from Kurt Gerstein ‘s “eyewitness account.” But he has not completely abstained from plagiarizing certain terms and expressions, as becomes apparent from the following comparison:

| Müller (1979a, pp. 184-186) | Nyiszli (1961, No. 4, p. 29) |

| Nach einigen Augenblicken befahl er dem Kommandoführer, die Ventilatoren einzuschalten, die das Gas absaugen sollten. […]. | Die modernen Saugventilatoren haben das Gas bald aus dem Raum entfernt. |

| Nach der Öffnung der Gaskammer … […]. Dabei wurde den Toten die Schlaufe eines Lederriemens um eines ihrer Handgelenke gelegt und zugezogen, um sie so in den Lift zu schleifen und nach oben ins Krematorium zu befördern. Als hinter der Tür etwas Platz geschaffen war, wurden die Leichen mit Wasserschläuchen abgespritzt. | Um die im Todeskampf zusammengeballten Fäuste werden Riemen geschnallt, an denen man die von Wasser glitschigen Toten zum Fahrstuhl schleift. […].

Das Sonderkommando in seinen Gummistiefeln stellt sich also rings um den Leichen-Berg auf und bespritzt ihn mit starkem Wasserstrahl. // das Sonderkommando, das jetzt mit Schläuchen hereinkommt…

|

| Damit sollten Glaskristalle, die noch herumlagen, neutralisiert, aber auch die Leichen gesäubert werden. Denn fast alle waren naß von Schweiß und Urin, mit Blut und Kot beschmutzt, und viele Frauen waren an den Beinen mit Menstruationsblut besudelt. | Das muß sein, weil sich beim Gastod als letzte Reflexbewegung der darm entleert. Jeder Tote ist beschmutzt. |

| Wenn die eingeworfenen Zyklon-B-Kristalle mit Luft in Berührung kamen, entwickelte sich das tödliche Gas, das sich zuerst in Bodenhöhe ausbreitete und dann immer höher stieg. Daher lagen auch oben auf den Leichenhaufen die Größten und Kräftigsten, während sich unten vor allem Kinder, Alte und Schwache befanden. Dazwischen fand man meist Männer und Frauen mittleren Alters. Die Obenliegenden waren wohl in ihrer panischen Todesangst auf die schon am Boden Liegenden hinaufgestiegen, weil sie noch Kraft dazu und vielleicht auch erkannt hatten, daß sich tödliche Gas von unten nach oben ausbreitete. […]. | Das Cyclon entwickelt Gase, sobald es mit Luft in Berührung kommt. […]. Die Leichen liegen nicht im Raum verstreut, sondern türmen sich hoch übereinander. Das ist leicht zu erklären: Das von draußen eingeworfene Cyclon entwickelt seine tödliche Gase zunächst in Bodenhöhe. Die oberen Luftschichten erfaßt es erst nach und nach. Deshalb trampeln die Unglücklichen sich gegenseitig nieder, einer klettert über den anderen. Je höher sie sind, desto später erreicht sie das Gas. […]. Wenn sie in ihrer verzweifelten Todesangst… Ich sehe, daß Säuglinge, Kinder und Greise ganz unten liegen, darüber dann die kräftigeren Männer. |

| Auf den Leichenhaufen waren die Menschen ineinander verschlungen, manche lagen sich noch in den Armen, viele hatten sich im Todeskampf noch die Hände gedrückt, an den Wänden lehnten Gruppen, aneinandergepreßt, wie Basaltsäulen. | Um die im Todeskampf zusammengeballten Fäuste… |

| Die Leichenträger hatten Mühe, die Toten auf den Leichenhaufen auseinanderzuzerren. Viele hatten den Mund weit aufgerissen, auf den Lippen der meisten war eine Spur von weißlichem, eingetrocknetem Speichel zu erkennen. Manche waren blau angelaufen, und viele Gesichter waren von Schlägen fast bis zur Unkenntlichkeit entstellt. […]. | Ineinander verkrallt, mit blutig zerkratzten Leibern, aus Nase und Mund blutend, liegen sie da. Ihre Köpfe sind blau angeschwollen und bis zur Unkenntlichkeit entstellt. |

| Während die Toten aus der Gaskammer geschafft wurden, mußten die Leichenträger Gasmasken aufsezten; dann die Ventilatoren konnten das Gas nicht vollständig absaugen. Vor allem zwischen den Toten befanden sich noch immer Reste des tödlichen Gases, das beim Räumen der Gaskammer frei wurde. | Die modernen Saugventilatoren haben das Gas bald aus dem Raum entfernt.

Nur zwischen den Toten ist es noch in kleinen Mengen vorhanden. Deshalb trägt das Sonderkommando, das jetzt mit Schläuchen hereinkommt, Gasmasken. |

| Müller | Gerstein[6] |

| …viele hatten sich im Todeskampf noch die Hände gedrückt, … | Sie drücken sich, im Tode verkrampft, noch die Hände… |

| …an den Wänden lehnten Gruppen, aneinandergepreßt, wie Basaltsäulen. | Wie Basaltsäulen stehen die Toten aufrecht aneinandergepresst in den Kammern. |

| Denn fast alle waren naß von Schweiß und Urin, mit Blut und Kot beschmutzt, und viele Frauen waren an den Beinen mit Menstruationsblut besudelt. | Man wirft die Leichen – nass von Schweiss und Urin, kotbeschmutzt, Menstruationsblut an den Beinen, heraus. |

Also in this case, the examination of the two full-text passages reveals that the plagiarism is much deeper than is revealed by this comparison. In order to enable the skilled reader to compare the original German text passages, I report here both the German text and the English translation. Here is Müller’s account, German version (1979a, pp. 184-186):

“Nach einigen Augenblicken befahl er dem Kommandoführer, die Ventilatoren einzuschalten, die das Gas absaugen sollten. […]

Nach der Öffnung der Gaskammer wurde zuerst befohlen, die herausgefallenen Leichen und dann die hinter der Tür liegenden wegzuschaffen, um den Zugang freizumachen. Dabei wurde den Toten die Schlaufe eines Lederriemens um eines ihrer Handgelenke gelegt und zugezogen, um sie so in den Lift zu schleifen und nach oben ins Krematorium zu befördern.

Als hinter der Tür etwas Platz geschaffen war, wurden die Leichen mit Wasserschläuchen abgespritzt. Damit sollten Glaskristalle, die noch herumlagen, neutralisiert, aber auch die Leichen gesäubert werden. Denn fast alle waren naß von Schweiß und Urin, mit Blut und Kot beschmutzt, und viele Frauen waren an den Beinen mit Menstruationsblut besudelt.

Wenn die eingeworfenen Zyklon-B-Kristalle mit Luft in Berührung kamen, entwickelte sich das tödliche Gas, das sich zuerst in Bodenhöhe ausbreitete und dann immer höher stieg. Daher lagen auch oben auf den Leichenhaufen die Größten und Kräftigsten, während sich unten vor allem Kinder, Alte und Schwache befanden. Dazwischen fand man meist Männer und Frauen mittleren Alters. Die Obenliegenden waren wohl in ihrer panischen Todesangst auf die schon am Boden Liegenden hinaufgestiegen, weil sie noch Kraft dazu und vielleicht auch erkannt hatten, daß sich das tödliche Gas von unten nach oben ausbreitete.

Auf den Leichenhaufen waren die Menschen ineinander verschlungen, manche lagen sich noch in den Armen, viele hatten sich im Todeskampf noch die Hände gedrückt, an den Wänden lehnten Gruppen, aneinandergepreßt wie Basaltsäulen.

Die Leichenträger hatten Mühe, die Toten auf den Leichenhaufen auseinanderzuzerren, obwohl sie noch warm und noch nicht erstarrt waren. Viele hatten den Mund weit aufgerissen, auf den Lippen der meisten war eine Spur von weißlichem, eingetrocknetem Speichel zu erkennen. Manche waren blau angelaufen, und viele Gesichter waren von Schlägen fast bis zur Unkenntlichkeit entstellt. […]

Während die Toten aus der Gaskammer geschafft wurden, mußten die Leichenträger Gasmasken aufsetzen; denn die Ventilatoren konnten das Gas nicht vollständig absaugen. Vor allem zwischen den Toten befanden sich noch immer Reste des tödlichen Gases, das beim Räumen der Gaskammer frei wurde.”

The following is Müller’s published English version (1979b, pp. 116-118):

“After a while he ordered the Kommandoführer to switch on the fans which were to disperse the gas. […]

We had orders that immediately after the opening of the gas chamber we were to take away first the corpses that had tumbled out, followed by those lying behind the door, so as to clear a path. This was done by putting the loop of a leather strap round the wrist of a corpse and then dragging the body to the lift by the strap and thence conveying it upstairs to the crematorium. When some room had been made behind the door, the corpses were hosed down. This served to neutralize any gas crystals still lying about, but mainly it was intended to clean the dead bodies. For almost all of them were wet with sweat and urine, filthy with blood and excrement, while the legs of many women were streaked with menstrual blood.

As soon as Zyclon B crystals came into contact with air the deadly gas began to develop, spreading first at floor level and then rising to the ceiling. It was for this reason that the bottom layer of corpses always consisted of children as well as the old and the weak, while the tallest and strongest lay on top, with middle-aged men and women in between. No doubt the ones on top had climbed up there over the bodies already lying on the floor because they still had the strength to do so and perhaps also because they had realized that the deadly gas was spreading from the bottom upwards. The people in their heaps were intertwined some lying in each other’s arms, others holding each other’s hands; groups of them were leaning against the walls, pressed against each other like columns of basalt.

The carriers had great difficulty in prising the corpses apart, even though they were still warm and not yet rigid. Many had their mouths wide open, on their lips traces of whitish dried-up spittle. Many had turned blue, and many faces were disfigured almost beyond recognition from blows. […]

During the removal of corpses from the gas chamber bearers had to wear gas-masks because the fans were unable to disperse the gas completely. In particular there were remnants of the lethal gas in between the dead bodies, and this was released during cleaning out operations.”

Here is Nyiszli ‘s German tale, as Müller could access it (1961, No. 4, p. 29):

“Das Cyclon entwickelt Gase, sobald es mit Luft in Berührung kommt. […]

Die modernen Saugventilatoren haben das Gas bald aus dem Raum entfernt. Nur zwischen den Toten ist es noch in kleinen Mengen vorhanden. Deshalb trägt das Sonderkommando, das jetzt mit Schläuchen hereinkommt, Gasmasken.

Ein grauenhaftes Bild bietet sich:

Die Leichen liegen nicht im Raum verstreut, sondern türmen sich hoch übereinander. Das ist leicht zu erklären: Das von draußen eingeworfene Cyclon entwickelt seine tödlichen Gase zunächst in Bodenhöhe. Die oberen Luftschichten erfaßt es erst nach und nach. Deshalb trampeln die Unglücklichen sich gegenseitig nieder, einer klettert über den anderen. Je höher sie sind, desto später erreicht sie das Gas. Welch furchtbarer Kampf um zwei Minuten Lebensverlängerung… […]

Ineinander verkrallt, mit blutig zerkratzten Leibern, aus Nase und Mund blutend, liegen sie da. Ihre Köpfe sind blau angeschwollen und bis zur Unkenntlichkeit entstellt. […]

Das Sonderkommando in seinen Gummistiefeln stellt sich also rings um den Leichenberg auf und bespritzt ihn mit starkem Wasserstrahl. Das muß sein, weil sich beim Gastod als letzte Reflexbewegung der Darm entleert. Jeder Tote ist beschmutzt.

Nach dem ‘Baden’ der Toten werden die verkrampften Leiber voneinander gelöst. Eine furchtbare Arbeit. Um die im Todeskampf zusammengeballten Fäuste werden Riemen geschnallt, an denen man die vom Wasser glitschigen Toten zum Fahrstuhl schleift.”

And finally, my translation of this early German version of Nyiszli ‘s account:

“The cyclone develops gases as soon as it comes into contact with air. […]

The modern suction fans soon removed the gas from the room. It is only present in small quantities between the dead. That’s why the Sonderkommando that comes in with hoses is wearing gas masks.

A horrific picture presents itself:

The corpses are not scattered around the room, but are piled high on top of each other. This is easy to explain: The cyclone thrown in from outside initially develops its deadly gases at ground level. It gets into the upper layers of air only gradually. That is why the unfortunate people trample each other down, one climbing over the other. The higher they are, the later the gas reaches them. What a terrible fight for two minutes of life extension … […]

They lie there, clinging to each other, with bodies scratched bloody, bleeding from nose and mouth. Their heads are swollen blue and disfigured beyond recognition. […]

The Sonderkommando in their rubber boots therefore position themselves around the mountain of corpses and sprays it with a strong jet of water. That has to be, because during the gassing death throes, the bowels empty out as a last reflex. Every dead person is soiled.

After ‘bathing’ the dead, the intertwined bodies are released from each other. A terrible job. Around the fists, clenched together in agony, straps are wrapped and are used to drag the dead, slippery from the water, to the elevator.”

In this case it is utterly impossible that Müller had observed the same scenario as described by Nyiszli, because it was invented by the Hungarian physician based on the erroneous assumption that Zyklon B consisted of chlorine. In the translation plagiarized by Müller, Nyiszli speaks of “Cyclon, a form of chlorine” (“Cyclon, eine Form von Chlor”; ibid.), but the original Hungarian text reads: “Cyclon, vagy Chlór szemcsés formája,” meaning “Cyclon, or chlorine in granular form” (Mattogno 2020a, p. 40). As I have explained in my study on Nyiszli (ibid., p. 219), chlorine has a density of 2.45 with respect to air, therefore it is heavier than air, Hence, during a hypothetical gassing using chlorine, it would at least theoretically create the scenario described by Nyiszli: it would first permeate the lower air layers and then gradually the rest of the “gas chamber” from bottom to top, like a container that gradually fills with a liquid. The density of gaseous hydrogen cyanide, on the other hand, is 0.97 relative to air, therefore it is slightly lighter than air, so that, if anything, it would theoretically create exactly the opposite scenario: it would first fill the higher air layers and then gradually fill the “gas chamber” from top to bottom. In practice, however, it would actually fill all the air layers at the same time, as the density difference is too small to cause any such behavior.[7]

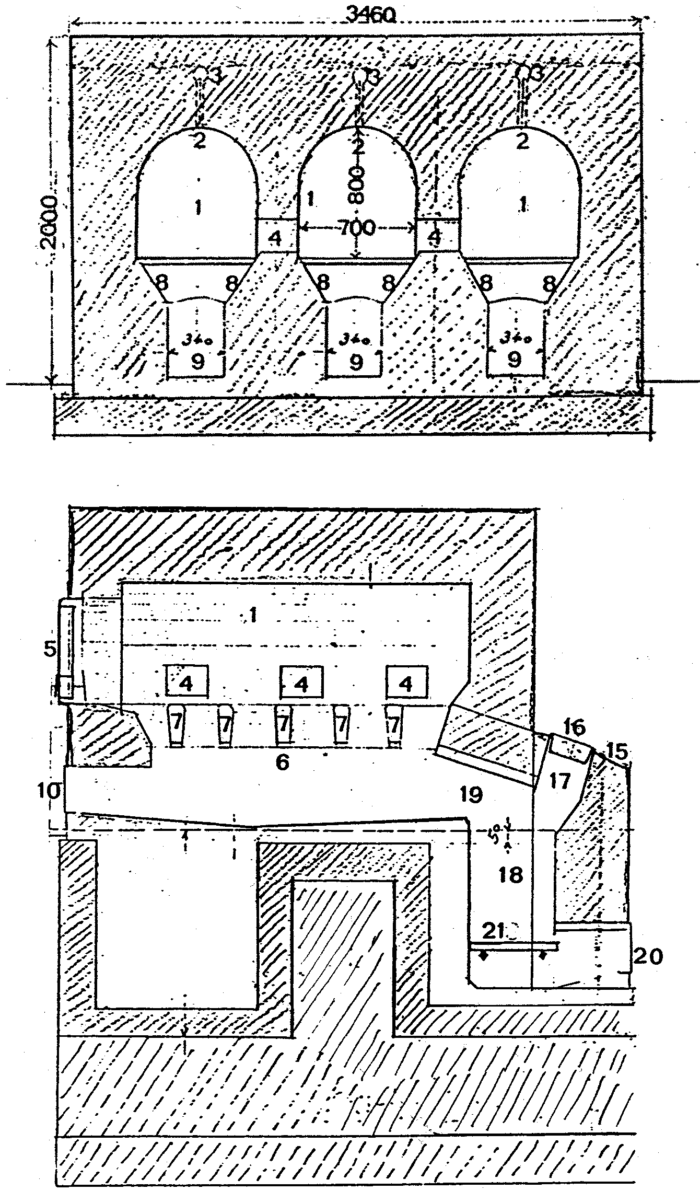

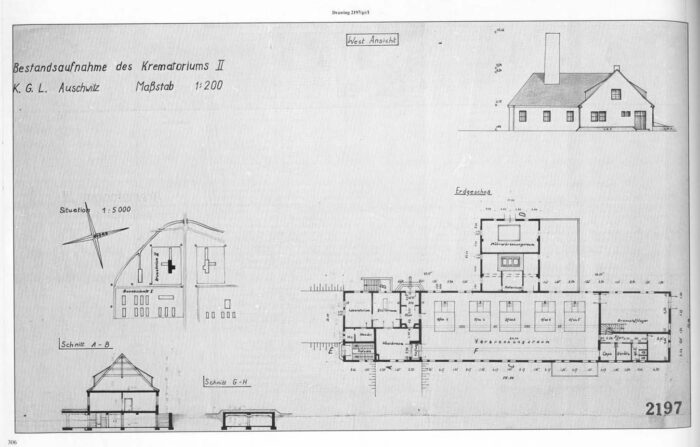

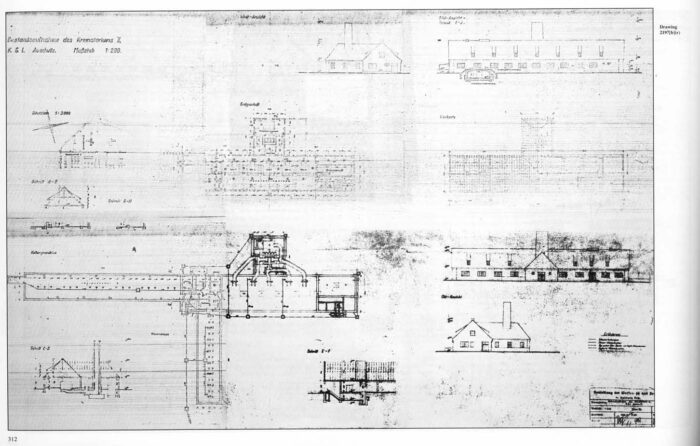

The scenario invented by Nyiszli presents another material impossibility. He staged the gassing of 3,000 people in Morgue #1 of Crematorium II, the alleged gas chamber. As I documented in a specific paper,[8] under such conditions – but also with a third of the claimed victims or less – the bodies of the victims would have obstructed the air-extraction openings of the alleged gas chamber, which were located at floor level, 20 on each side of the room, making the extraction of the toxic fumes and consequently any successful ventilation impossible. Therefore, after each gassing, when the door was opened, the hydrogen-cyanide vapors would have wafted throughout the entire basement of the crematorium and partly also the furnace room. For Nyiszli, however, the “modern suction fans soon removed the gas from the room,” which is pure nonsense.

Müller in turn also staged the scene in Crematorium II, but he does not explicitly say that 3000 victims were crammed into Morgue #1. However, he mentions this figure as the capacity of the alleged gas chamber, so he tacitly assumed it also in the plagiarism set out above (1979b, p. 60):

“Every detail had been devised with the sole aim of cramming up to 3000 people into one room in order to kill them with poison gas.”

He didn’t have the faintest idea how the ventilation system was designed, because in this regard he states about the “gas chamber” (ibid., 61):

“A ventilating plant was installed in the wall; this was switched on immediately after each gassing to disperse the gas and thus to expedite the removal of corpses.”

In fact, Morgue #1 of Crematoria II and III was ventilated by two blowers, one extracting the air, the other supplying fresh air, which both had the same power and capacity, and were installed in the attics of the crematoria, not in the morgue’s wall. In the study mentioned earlier, I thoroughly described the entire ventilation system of these crematoria.[9]

The blue color of some corpses is a well-known but utterly false stereotype of post-war testimonies. It is well-established, however, that the most-frequent color of cyanide-poisoning victims is pink-red (Trunk, p. 40; Rudolf 2020, pp. 228-230).

Like the source he plagiarized, Müller was unaware of the existence of a waste incinerator (Müllverbrennungsofen) in Crematoria II and III,[10] because he never mentions it, but above all because he reports that “prayer-books and religious works, and also other books” – which according to Nyiszli were burned by the “Dayan” on “the so-called Canada rubbish heap,” as mentioned earlier – were burned “in one of the furnaces of Crematorium III.”[11]

Müller’s description of the devices allegedly used to introduce Zyklon B into the claimed gas chambers of Crematoria II and III also reveals his plagiarism, although Müller added his own nonsense to it:

| Müller (1979a, p. 96; 1979b, p. 60) | Nyiszli (1961, No. 4, p. 29) |

| “Die Zyklon-B-Gas-Kristalle wurden nämlich durch Öffnungen in der Betondecke eingeworfen, die in der Gaskammer in hohle Blechsäulen einmündeten. Diese waren in gleichmäßigen Abständen durchlöchert und in ihrem Innern verlief von oben nach unten eine Spirale, um für eine möglichst gleichmäßige Verteilung der gekörnten Kristalle zu sorgen.” | “In der Mitte des Saales stehen im Abstand von jeweils dreißig Metern Säulen. Sie reichen vom Boden bis zur Decke. Keine Stützsäulen, sondern Eisenblechrohre, deren Wände überall durchlöchert sind.” |

| “The Zyclon B gas crystals were inserted through openings [in the concrete ceiling, which in the gas chamber led] into hollow pillars made of sheet metal. They were perforated at regular intervals and inside them a spiral ran from top to bottom in order to ensure as even a distribution of the granular crystals as possible.” | “In the middle of the hall there are columns at a distance of thirty meters. They go from floor to ceiling. No support columns, but sheet-iron pipes, the walls of which are perforated everywhere.” |

It goes without saying that the “official” devices, as sanctioned by the Auschwitz Museum, were structured in a completely different way:

“The Zyklon B gas was introduced to the gas chambers through four specially built devices constructed in the camp machine shops. They were shaped like vertical rectangular pillars, 70 cm wide and about 3 m. high, made of two layers of wire mesh with a sliding core section.” (Piper 2000, p. 166)

Müller’s addition to the tale – the inner spiral – is foolish, because the sheet-metal enclosure of those columns would have prevented the spiral from evenly distributing the “granular crystals,” which instead would have simply piled up within seconds inside the columns on the floor at the end of the spiral. When plagiarizing Nyiszli ‘s gassing tale, Müller forgot the columns again and instead stated that “gas crystals” were “still lying about” (1979b, p. 117), meaning that they were scattered out on the floor of the “gas chamber” so much so that they had to be neutralized with jets of water.

Since Nyiszli did not indicate the number of these devices, neither did Müller, who claims to have seen them personally many times.

Already earlier I dwelt on the tale of the Zyklon-B “crystals”. Müller affirmed that they turned into gas on contact with air, a nonsense he also copied from Nyiszli ‘s narration. It is well known that the evaporation rate of hydrogen cyanide from the inert carrier material essentially depended on the ambient air temperature and humidity, and required no contact with anything.

Müller asserted that each crematorium had a single “gas chamber” of about 250 square meters which was characterized by an “unusually low ceiling” (1979b, p. 60), which may be a vague echo of Bendel ‘s statement that the alleged gas chambers were only some 1.5 meters high (Mattogno 2020a, pp. 310-312); but the room in question, Morgue #1, measured 30 m × 7 m and was 2.41 meters high (Pressac 1989, p. 286), and it does not appear that Müller was a giant of over two meters such as to consider a ceiling that high to be “unusually low”.

Nyiszli ‘s influence also appears in the “room next to the gas chamber” (Müller 1979b, p. 79) which did not exist, but which was invented by the Hungarian physician in the context of his tale of a girl who had survived a gassing (Nyiszli 1961, No. 7, p. 34):

“I carry her to the next room, where the gassing unit is changing for its work.”

4.3. Executions with a Blow to Nape of the Neck

Another plagiarism, less-striking but no-less-shameless, concerns the executions of prisoners with a blow to the nape of the neck. Müller devotes three full pages to the description of the execution of a group of prisoners which ends in this way (Müller 1979a, p. 115):

“At the end of the execution, some 30 naked bodies were lying behind the execution wall on the floor. […]

At these executions 6-mm small-bore rifles were used, and the shots were fired from a distance of 3 to 5 cm.”

The English translation turned 30 victims into 50 (1979b, p. 73):

“When the execution was over, fifty naked bodies were lying on the ground behind the wall. […]

At these executions 6mm small-bore guns were used and fired from a distance of about 3 to 5 centimetres.”

His source, Nyiszli, stated (Mattogno 2020a, p. 50):

“The entrance hole reveals that it originates from a 6-millimeter, so-called small-caliber weapon; there is no exit-wound hole. […]

I am no longer surprised either that the small-caliber bullets did not cause immediate death for all the victims, even though the shots were fired from a distance of 3-4 centimeters, as the burns on the skin show, straight in the direction of the brain stem.”

Even the description of the victims was plagiarized (Müller 1979b, p. 73):

“A few were still breathing stertorously, their limbs moving feebly while they sought to raise their blood-stained heads; their eyes were wide open: the victims were not quite dead because the bullets had missed their mark by a fraction.”

And here is Nyiszli ‘s original (Mattogno 2020a, pp. 49f.):

“Some among them are still alive, they make slow movements with their arms and legs and keep trying to lift their bloodied heads, eyes opened wide.

I lift one of the still-moving heads, then a second one, then a third, […] It appears the gun was off by 1-2 millimeters, and thus it did not cause immediate death.”

Here too, the context categorically refutes that Müller saw the same scenes described by Nyiszli. For Müller, single Jews or small groups of Jews who had been captured while trying to escape from the ghettos of Sosnowice and Będzin, were sent to Birkenau to be shot in the nape of the neck, rather than being gassed like everyone else, although it is unclear why. The execution Müller described took place in the “execution room” or “shooting room” of Crematorium V[12] and concerned precisely “a small group of Jewish families” (ibid., p. 71), including children, made up, as quoted earlier, of some 30 people (or 50, in the English text).

For Nyiszli, on the other hand, the execution took place in Crematorium II, involved 70 regular camp inmates, and was common practice (Mattogno 2020a, p. 50):

“I ask one of the Sonderkommando where the seventy unfortunates came from. They are the selected from camp section C, he replies, every evening at seven a truck brings seventy over. They all get a shot to the back of the neck.”

Müller wrote moreover (Müller 1979b, pp. 67f.):

“In 1941 I read in a fascist Slovak daily that the Third Reich no longer needed gold reserves to support its economy, since there was now a new and much fairer system, based on its citizens’ enthusiasm for work and far superior to the fraudulent Jewish-plutocratic economic system. Two years later the hypocritical mendacity of these phrases was demonstrated before my very eyes.

Towards the end of the summer of 1943 a workshop for melting gold was set up in crematorium 3.”

In that workshop, evidently gold teeth extracted from gassing victims are said to have been processed. Nyiszli had made a similar statement already much earlier (Mattogno 2020a, p. 71):

“Their whole financial system is based on false foundations. Countless times they have trumpeted to the world that the foundational value of the National-Socialist Third Reich is not gold, but work! And yet, in a facility established specifically for this purpose, every day they smelt 30-40 kilos of gold from the teeth of Jews brought here and murdered.”

However, in the 1961 German translation, the passage saying “every day they smelt 30-40 kilos of gold from the teeth of Jews” was omitted, and recognizing this impossibly high figure, the translator drastically reduced it and instead claimed “eight to ten kilos” (“acht bis zehn Kilo,” Nyiszli 1961, No. 4, p. 29). Inspired by this, Müller probably transformed this figure to his claim that “frequently they melted down between 5 and 10 kilogrammes a day” (Müller 1979b, p. 68).[13]

4.4. Further Plagiarisms and Contradictions

Müller also copied from Nyiszli the reference to Noma, or oral cancer, which affects the soft and bony tissues of the mouth especially in children. He claims to have seen in the crematorium the corpses of children from the Gypsy Camp who had been affected by this disease. The inmates of the “Sonderkommando” believed that these corpses had been mauled by rats, but the physicians explained to them that it was Noma (Müller 1979b, p. 149), a topic that, among the “Sonderkommando” witnesses, was mentioned exclusively by Nyiszli (1961, No. 3, p. 31).

The events of the evacuation from Birkenau and the transfer to Mauthausen run parallel in Müller’s and Nyiszli ‘s story, without the two ever encountering each other.[14]

Both were in Crematorium V on the night when the inmates were gathered for evacuation,[15] Nyiszli and his three aides alone, four people in all, because the 30 inmates who ran the furnaces were not part of the “Sonderkommando,” hence they were staying in Auschwitz. Müller, on the other hand, claims to have been part of the group of 30 “Sonderkommando” inmates who were assigned to the crematorium. “Towards midnight” (“gegen Mitternacht”) Nyiszli was awakened with a start by loud explosions; the crematorium was not guarded, so he and his aides fled, crossed the Birkenau grove (“durchqueren den kleinen Birkenauer Wald”) and joined the mass of inmates. Müller instead saw “during the late afternoon” (“im Laufe des späten Nachmittags”) a Blockführer arrive who ordered the “Sonderkommando” to vacate the crematorium, and they all ran across the Birkenau grove (“liefen quer durch das Wäldchen”), and went to Camp Sector BIId, where the other 70 inmates of the demolition team were housed. Only then did they rejoin the large mass of about 20,000 inmates, who then marched to Loslau (today’s Wodzisław Śląnski), from where they continued on to Mauthausen.

In addition to Nyiszli, Müller also used Czech ‘s “Auschwitz Chronicle” to create this story, in which he read precisely that

“in the afternoon, a column of around 1,500 prisoners left Camp [Sector] BIId in Birkenau. This column also included the Sonderkommando with 30 inmates, the demolition team of the crematorium with 70 inmates, and the penal squad with around 400 inmates.”

These inmates then marched toward Wodzisław Śląnski (Czech 1964b, pp. 99f.). Dragon, on the other hand, denied it all and asserted instead:[16]

“All of us who remained alive were transferred and quartered at Crematorium No. III. I stayed in Crematorium No. III until November 1944. Subsequently the entire Sonderkommando was transferred to the BIId Camp. I was in Block 13. […] I remained in Block 13 of the BIId Camp until the beginning of January 1945. Then I was transferred with all the Sonderkommando to Block 16, from where on January 18 we were sent with a transport to the Reich.”

Müller also copied from Nyiszli, with some embellishments, the nonsensical anecdote of the search for “Sonderkommando” inmates at Mauthausen, which the latter presented as follows (Nyiszli 1961, No. 11, p. 51):

“On the third day, two SS officers appear. Who of us has worked in the Auschwitz crematoria, they want to know.”

And here is Müller’s version (1979b, p. 167):

“On the third day after our arrival we had lined up for roll-call in the late afternoon, when out of the blue one of the SS-Unterführers gave the order: ‘All prisoners of the Auschwitz Sonderkommando, fall out!’”

This is clearly a nonsensical fabrication. The inmates were transferred with name lists, on which Filip Müller’s name also appears.[17] Over 5,700 prisoners who had left Auschwitz on January 18, 1945 arrived at Mauthausen on the 25th and were registered under numbers 116501-122225 (Het Neederlandsche…, p. 85). If we were to believe Nyiszli ‘s and Müller’s tale, we would have to assume that the SS, after exterminating the “Sonderkommando” inmates several times as “carriers of secrets” in Auschwitz, and after carefully erasing the traces of the alleged mass extermination at Birkenau, left the last 100 “Sonderkommando” inmates alive. Indeed, after the “last gassing,” which took place in November 1944 according to Müller,[18] these inmates had become utterly useless, in fact, a dangerous dead weight, and there was plenty of time to eliminate them. Inexplicably, however, the SS did not just leave them alive. During the evacuation, they allowed them to mingle with the other inmates, and only three days after the transport had arrived at Mauthausen, they made all the inmates line up, crazily shouting: “All prisoners of the Auschwitz Sonderkommando, fall out!” (implying: “So we can shoot them!”). And we are also to believe that the stupidity of the SS went so far as to being unable to pick out the “Sonderkommando” inmates from the name list that accompanied the deportees. In fact, when Auschwitz Inmate No. 29236 – Filip Müller, whose name is on that list – was registered at Mauthausen,[19] if he really had been wanted as a “carrier of secrets,” could have been identified easily, and could have been eliminated without the need for any roll call, just like all his other colleagues.

5. Plagiarized History of Birkenau: Kraus and Kulka

5.1. Kraus ‘s and Kulka ‘s Trial Declarations

In his book, Müller claims that he personally knew his countrymen Ota Kraus and Erich Kulka, the authors of the book Továrna na smrt, who recorded his statement as quoted in Subchapter 1.1. (Müller 1979a, p. 162):

“In great excitement I ran into the locksmith’s workshop around noon. There I met Otto Kraus, Laco Langfelder and Erich Schoen-Kulka, whose wife and son were also housed in the family camp. I had been friends with all of them for a long time, and each knew that he could rely on the other.”

The sanitized English edition has this compressed to (1979b, p. 102):

“In a state of great agitation I hurried to the repair shop during the lunch-break. There I met three fellow prisoners with whom I had long been on friendly terms. One of them, Erich Schoen, had his wife and son living in the Family Camp.”

Müller had learned of the upcoming liquidation of the Family Camp (Familienlager), and had rushed to tell his friends. During the interview with Lanzmann, Müller stated in this regard (2010, p. 102):

“Mü: Yes, a few times I thought about fleeing. I wanted to flee with my friends, Erich Kulka and Otto Kraus. We made a plan in the year, 1944, and we wanted to figure out how far to flee, but then this, this, our initiative became more difficult by the fact that Erich Kulka had a son, who was quite young and… he was about twelve or thirteen and he (might) survive Auschwitz, and because of this possibility, among other things, it got more difficult.”

Kraus and Kulka had been witnesses at the Höss Trial, where both testified during the 11th hearing. Kraus’s appearance was fleeting and irrelevant. He stated that he had spent five years in German concentration camps in Dachau, Sachsenhausen, Hamburg and two years in Birkenau. According to him, “all the witnesses of this extermination in Birkenau must have been exterminated, whereas the traces of these crimes were erased.” Regarding Birkenau, he only mentioned briefly a Jewish transport from Theresienstadt in September 1943.[20]

Kraus also participated in the Krakow trial against the Auschwitz camp garrison, and was interrogated during the 6th hearing. Here, the witness was a little more talkative. I summarize his statements about Birkenau:[21]

“The Brzezinka [Birkenau] camp was the extermination camp of all peoples. The Jews came first, then the Poles and Czechs had to follow.”

According to Kraus, 20% of the deportees were registered and sent to work, while the rest were killed.

“We made the lists ourselves at the camp, and according to our calculations, approximately 2 million citizens of the Polish Republic, 150,000 Czechs, 500,000 Hungarians, 250,000 Germans, 90,000 Dutch, 60,000 Belgians, 80,000 Greeks and several ten thousand Yugoslavs, Italians and others died in the gas chambers. This total amounts to three and a half million, mostly Jews. In addition, about 400,000 people who were political prisoners, so that the total number of deaths in Brzezinka amounts to 4,000,000.”

There is no need to comment on such numerical nonsense. When asked by Prosecutor Pęchalski regarding the source of these figures, Kraus replied:

“I got these figures from people who worked in the so-called ‘Kanada’ and the ‘Sonderkommando’ and from the secretaries at the Political Department.”

The witness did not mention Filip Müller.

During the Warsaw trial, Kulka testified right after Kraus. He stated that he had been in Auschwitz from 1942 until the camp’s evacuation. The selection assigned 80% of the deportees to be gassed, and only 20% to work. In February 1943, a commission of senior figures from the Reich, including Eichmann and Pohl, arrived at the camp, which is pure fiction. The witness then described the gassing of the inmates lodged in the Family Camp: first, 1,000 men were selected who were sent to Schwarzharz, 2,000 women who were transferred to Hamburg and Stutthof, finally 80 boys aged 14-16 who were sent to a German factory. “All the rest, 7,000-8,000 [detainees], were liquidated on July 10, 12, 1943 [sic].” All these figures are completely made-up and without basis in fact (see Mattogno 2016, pp. 160-164), but that didn’t stop Danuta Czech from incorporating them uncritically in her Auschwitz Chronicle by quoting the book Továrna na smrt, with only the date being corrected, which became July 10 and 11, 1944 (Czech 1990, p. 662).

Kulka then testified about the so-called “Operation Höss “ that took place at Birkenau from April to September 1944:

“At the time, 40,000 [which should read 400,000, as mentioned a few pages later] Hungarian Jews arrived at Birkenau, who were exterminated under horrible circumstances. The crematoria cremated 20,000 people a day.”

He also referred to his book: “I refer to Kraus ‘s book The Death Factory, which gives exact data on all these figures,” that is, 392,000 registered inmates, of whom 266,000 were men and 110,000 were women, plus 16,000 Gypsies. The book Továrna na smrt, written by Kraus and himself under the name of Erich Schön, had been published the year before.

Later the witness stated:

“I was present at the construction of the crematoria as a blacksmith, a profession that I practiced in the camp. I therefore had access to all the camps [camp sectors] and to all technical installations. I saw how the Germans, with great alacrity, steadily increased the crematoria’s capacity, and often the entire medical commission, of technicians and scientists from Berlin gathered there, who studied the gassing, and they always gave indications on how to improve the extermination of people.”

70,000 Jews had allegedly arrived from Theresienstadt, and 150,000 from all over the Czech Republic. Here, too, we are in fairytale land.

From their depositions it becomes clear that Kraus and Kulka knew practically nothing about the crematoria and the alleged gas chambers of Birkenau at that time.

5.2. The Death Factory

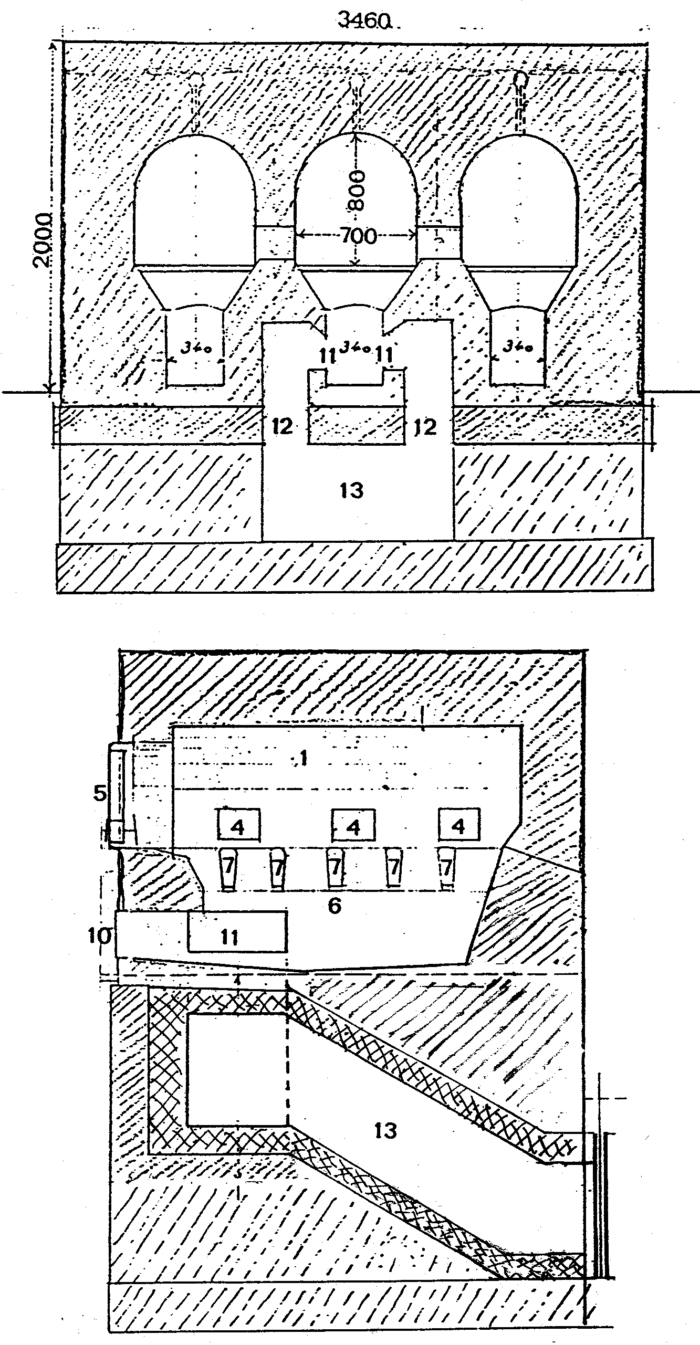

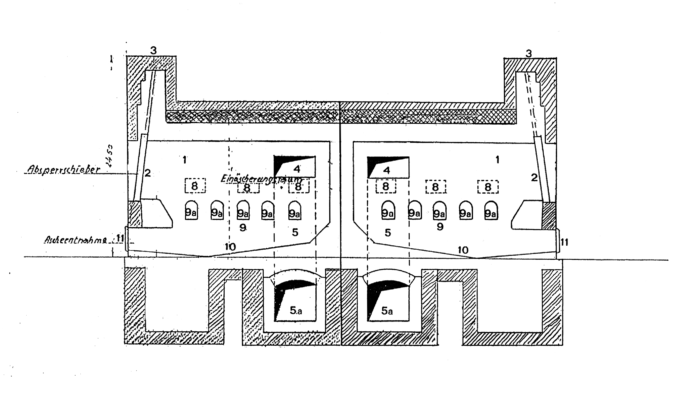

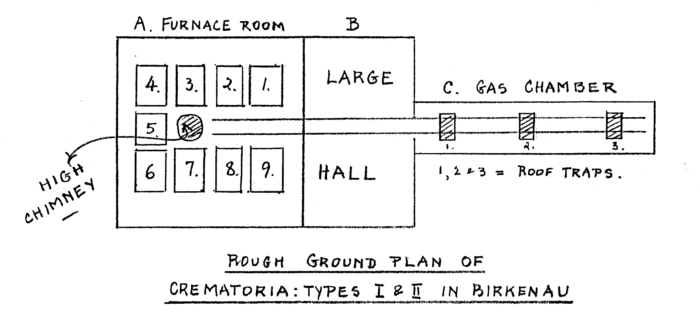

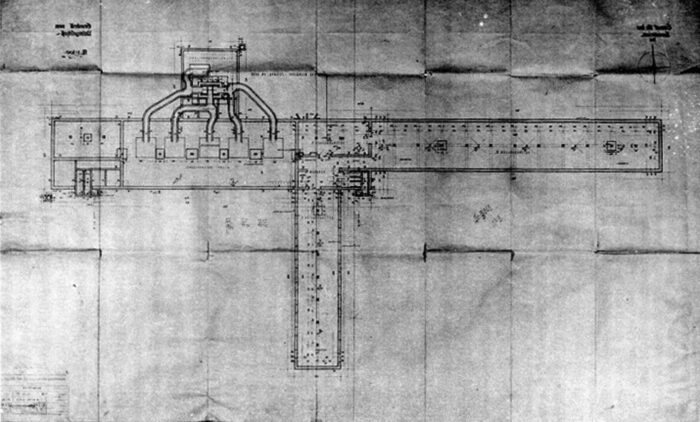

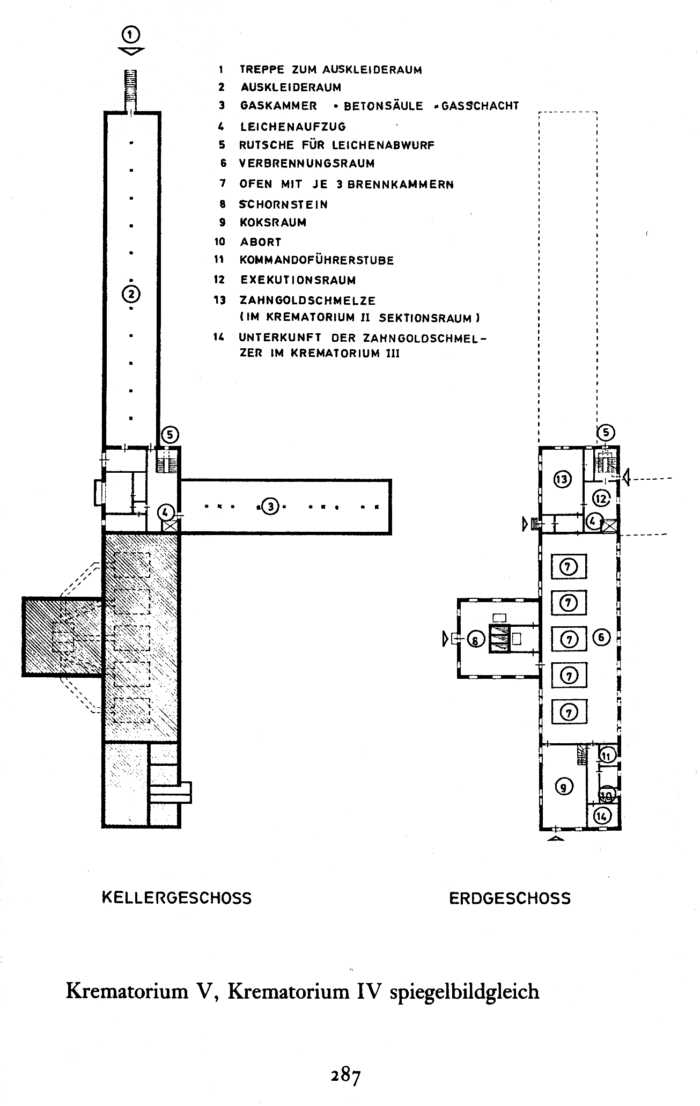

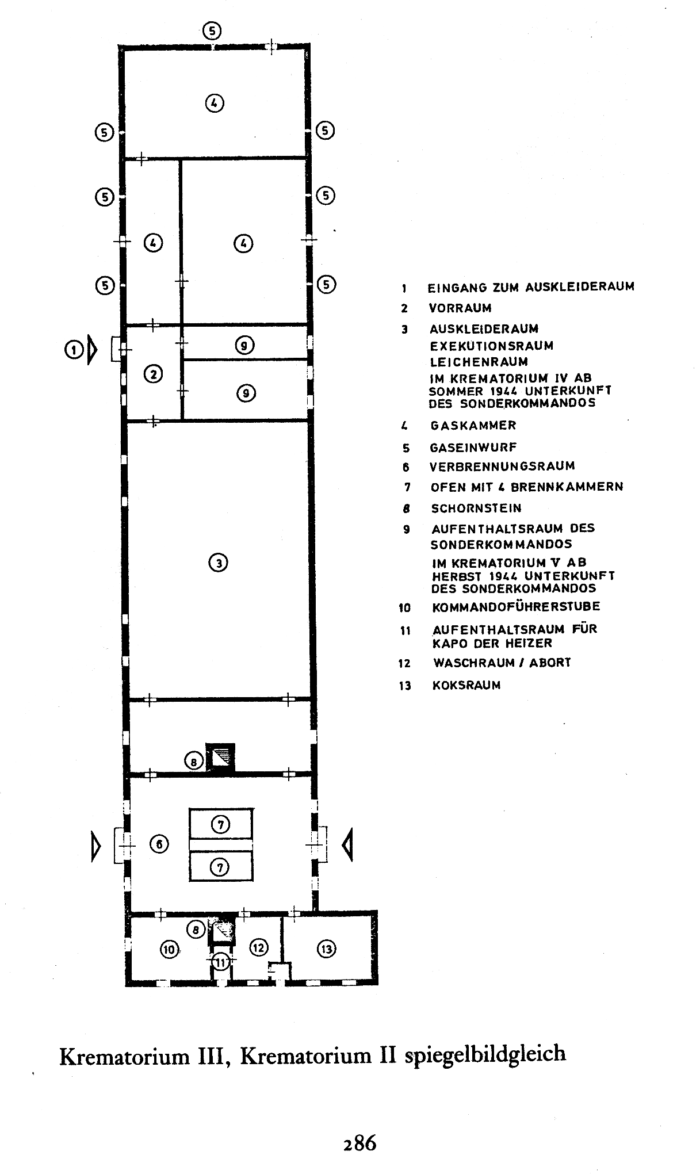

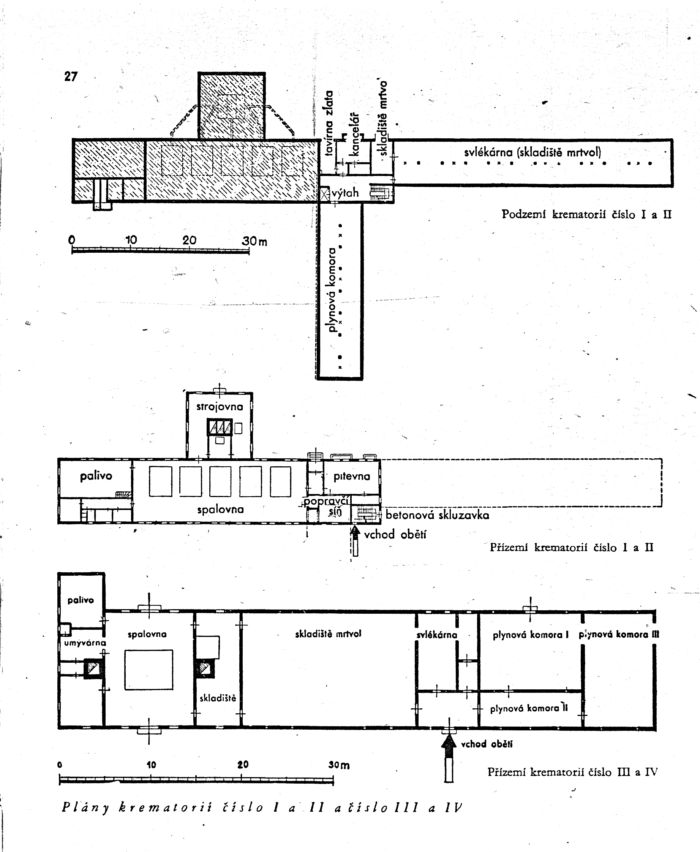

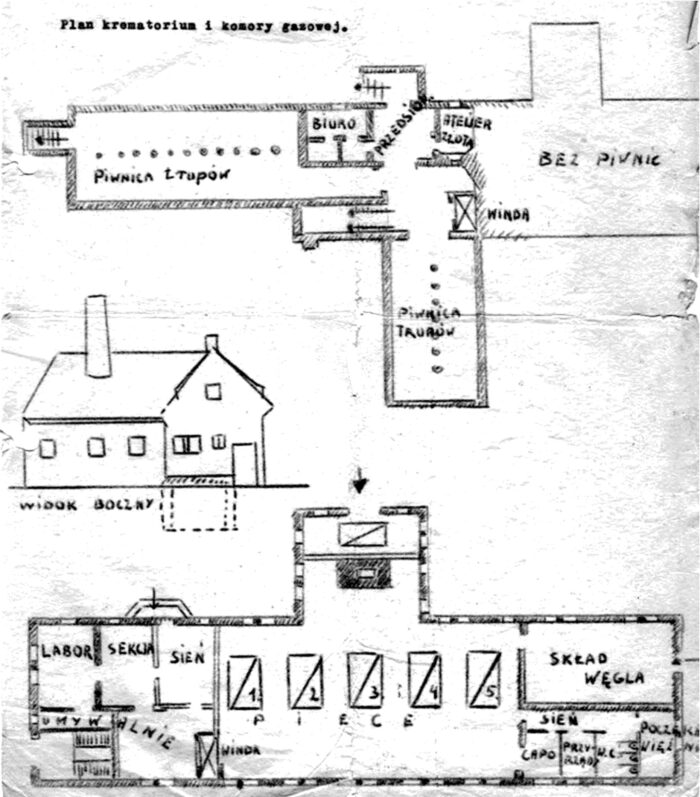

In Továrna na smrt, Kraus and Kulka had tried to put together all the knowledge of the time, especially in the Czech-speaking world. It is to their credit that they were the first to published fairly precise plans of the Birkenau crematoria. In this regard they wrote the following (here quoted from the English translation Kraus/Kulka 1966, pp. 127-130):

“Crematoria with Gas Chambers

The new crematoria with their gas chambers – corpse-processing factories – were no longer old converted cottages but modern buildings, carefully devised, planned and constructed by SS officers.

The construction was started in the autumn of 1942. They were built by thousands of prisoners[22] organized in building parties bearing the official titles: Arbeitskommando Krematorium I, II, III, IV. SS officers gave the Kapos directions in accordance with the plans drawn up at the enormous building office in Auschwitz I. The technical drawings for the furnaces were marked ‘Topf & Sons, Erfurt’; they were dated 1937, which makes it clear that the Nazis were preparing and planning this crime, down to the last detail, long before they unleashed the Second World War.[23] The erection of the four Birkenau crematoria thus constitutes a culminating point in the Nazis’ organized attempt to break all resistance by freedom-loving mankind.

Crematoria I and II were large and were equipped with underground gas chambers; Crematoria III and IV were smaller, not so well appointed, and the gas chambers were above ground. Crematoria I and II each had a single squat chimney, while Crematoria III and IV each had two chimneys.

The plans for these crematoria, reproduced in this book, come from the building office (Bauleitung) at Birkenau Camp whence they were removed by Vera Foltýnová, an architect who worked there. We sent these plans to Czechoslovakia in August, 1944, by Fabián Sukup because at that time we assumed that both the crematoria and we ourselves would be liquidated as witnesses to German crimes. The removal of inconvenient witnesses was a normal occurrence throughout the Third Reich, especially in the concentration camps.

At first sight the crematoria – one-storey buildings in German style, with steep roofs, barred windows and dormer windows – presented the appearance of large bakeries. The space around them was enclosed by high tension barbed wire and was always well kept. The roads were sprayed with sand, and well-tended flowers bloomed in the beds on the lawn. The underground gas chambers, projecting some 20 in. above ground level, formed a grassy terrace. A person coming to the crematoria for the first time could have no idea what these industrial-looking buildings were actually for.

Crematoria I and II were close to the camp itself and were visible from all sides. Crematoria III and IV, on the other hand, were hidden in a little wood; tall pine trees and birches concealed the tragedies that befell millions. This place was called Brzezinka, from which the name Birkenau is derived. Around the crematoria were long, high piles of wood which was used for burning corpses, mainly in the pits.

At Crematoria I and II there were two underground rooms. The larger of these was an undressing-room and was occasionally used as a mortuary; the other was a gas chamber. The whitewashed undressing-room had square concrete pillars, about 12 ft apart, down the middle. Along the walls and round the pillars there were benches, with coat-hooks surmounted by numbers. A pipe with a number of water taps ran the entire length of one of the walls. There were the usual notices in several languages: no noise!, keep this place clean and tidy!, and arrows pointing to the doors bearing the words: disinfection, bathroom. The gas chamber was somewhat shorter than the undressing-room and looked like a communal bathroom. The showers in the roof, of course, were not used for water. Water taps were placed along the walls. Between the concrete pillars were two iron pillars, 1 ft x 1 ft, covered in thickly plaited wire. These pillars passed through the concrete ceiling to the grassy terrace mentioned above; here they terminated in airtight trap-doors into which the SS men fed the cyclon gas. The purpose of the plaited wire was to prevent any interference with the cyclon crystals. These pillars were a later addition to the gas chambers and hence do not appear in the plan.

Each of the gas chambers at Crematoria I and II was capable of accommodating up to 2000 people at a time.

At the entrance to the gas chamber was a lift, behind double doors, for transporting the corpses to the furnace-rooms on the ground-floor, with their 15 three-stage furnaces.[24] At the bottom stage air was driven in by electric fans, at the middle the fuel was burnt, and at the top the corpses were placed, two or three at a time, on the stout fire-clay grate. The furnaces had cast-iron doors which were opened by means of a pulley. [[25]…]

Crematoria III and IV, though smaller, worked faster than Crematoria I and II. Each had three gas chambers above ground, accommodating more than 2000 people at once, and eight furnaces.

The four crematoria together had eight gas chambers with a capacity of 8000 people; there were forty-six furnaces all told, each capable of burning at least three bodies in 20 minutes.”

The Czech text in the 1957 edition of Továrna na smrt (Kraus/Kulka 1957a, pp. 143-156), of which the texts in Die Todesfabrik and The Death Factory are fairly accurate translations, is basically identical to the text of the first edition of 1946 (pp. 120-123; it merely has a few stylistic changes). This means that in the eleven years that elapsed between the two editions, the authors did not feel they had to add anything to their meager description and, strangely enough, made no reference to the results of the Warsaw and Krakow trials (they merely reported the sentences imposed on the 40 defendants in the second trial; 1957a, p. 277). They did not mention the testimony of any self-proclaimed “Sonderkommando” member such as Stanisław Jankowski, Henryk Mandelbaum, Szlama Dragon or Henryk Tauber.

In summary, when Kraus and Schön-Kulka wrote their book in 1946, the situation was as follows:

- They did not know any eyewitnesses of the Birkenau “Sonderkommando,” other than František Feldmann, whom I will discuss later. In 1947, Kraus said that he had had contact with inmates of the “Sonderkommando” who (along with other sources) had provided him the figures of the gassings and that “all the witnesses of this extermination in Birkenau,” therefore most certainly the “Sonderkommando” inmates, “must have been exterminated.”

- They published fairly precise plans of Crematoria II-III and IV-V,[26] which they had received from the prisoner Věra Fortýnová, who had stolen them from the planning office of the Central Construction Office.

- They published two photographs of a three-dimensional model of Crematorium III[27] and also

- a photograph of the Topf coke-fired triple-muffle furnace in the Buchenwald crematorium,[28] whose design was identical to that of the furnaces set up in Crematoria II and III at Birkenau.[29]

- They were longtime friends of Müller and had been interned with him in Birkenau.

Given these circumstances, can anyone seriously believe that the authors, who had at their disposal an authentic “Sonderkommando” member of Birkenau who had been a stoker, had worked in Crematoria II, III and V, could explain the floor plans and the models of the crematoria in great detail, and provide invaluable information on the gassing and cremation techniques – can anyone seriously believe, I repeat, that the authors would have been content with a trite statement from that person merely dealing with the Main Camp crematorium as quoted in Subchapter 1.1.? The question is patently rhetorical.

Müller’s statement published by Kraus and Kulka thus indisputably demonstrates that they knew at the time that Müller was not part of the “Sonderkommando” of Birkenau, even if they pretended to believe in his self-definition as a “member of the Auschwitz and Birkenau Sonderkommando.”

This is evident beyond a shadow of a doubt from how they presented his statement. This is inserted in a paragraph entitled “Zvláštní oddíl” (Sonderkommando), which I present here in full from the English translation published in 1966:[30]

“THE SPECIAL SQUAD (SONDERKOMMANDO)

The Sonderkommando (or ‘special squad’) was a group of prisoners whose appointment was equivalent to a death sentence, since nobody was allowed to leave the squad and had to continue working until he died or was killed. The work he had to perform was the most abominable that could possibly be imagined – the preparations for the mass murder of innocent people, men, women and children. Sometimes he had even to help in the murder of his own parents, wife, brothers, or sisters, and then consign them to the furnaces.

Prisoners sent to work with the Sonderkommando were personally selected by Schwarzhuber, Commandant of Birkenau.

The Sonderkommando helped the SS men with the work of undressing the people before they went into the gas chamber. They had to transport the corpses to the furnaces, or lay them in heaps and burn them, and clear away the ash. They cleaned out the gas chambers, and arranged the clothing, footwear and other personal belongings of the dead.

At the outset the Sonderkommando was composed exclusively of Jews. Subsequently Russians were included, and the last Sonderkommando had five Polish political prisoners whose death sentences were commuted into sentences to work in this squad.

The prisoner-doctors in the Sonderkommando had the task of extracting gold teeth from the corpses. The SS examined the mouth of each corpse before it was burned, and if any gold tooth was found to have been overlooked, the doctor was punished with twenty-five strokes of the whip. The teeth were tossed into locked boxes through a hole; then they were cleaned and melted down into fire-clay cubes[31] weighing 0.5 kg each by means of a petrol lamp. This work was done by two dental technicians, Katz and Feldmann, who were closed into a room under special guard.

In the autumn of 1944, František Feldmann, prisoner No. 36,661, who came from Trenčianské Teplice, told us that by that date they had melted down 2000 kg of gold. Every Tuesday a senior SS officer arrived with a vehicle to supervise the melting and take away the gold.

In accordance with orders from Berlin, the Sonderkommando was at all times kept strictly separate from the other prisoners who were forbidden to have any contact with it. The squad had its own doctor, and if any of its members fell ill they were examined in their respective blocks.

In Camp BIb the Sonderkommando lived in Blocks 22 and 23, and subsequently in Block 2. In Camp BIId they were accommodated in Block 13, and subsequently in Blocks 9 and 11. Finally they went to live in the attics of the crematoria.

Our contact with members of the squad was secret and fraught with danger. If we had been caught, it would have meant, at best, loss of our camp ‘freedom’ and relegation to the squad – or death!

The work assigned to the squad severely affected the mental health of its members. They became apathetic and insensitive, and the expression on their faces changed radically until they all appeared brutalized. When new prisoners detailed to join the squad learnt what they would have to do, they frequently broke down and refused to go. Alternatively they would walk voluntarily into the gas chamber or past the SS guards so as to get themselves shot.

The Sonderkommando had plenty of food, cigarettes and other necessities, for the victims of the gas chambers left a rich legacy behind them. The SS made no objection to their having liquor. Altogether there were up to 800 men in the squad, the number varying according to the number of convoys expected.

SS Moll, who was the Commandant for all the crematoria, gave short shrift to any prisoners who attempted to commit suicide. He would throw them live into the furnace. In one case he held the man half in the furnace and half out; then he left the furnace door ajar and threatened the others that the same thing would happen to them if they did not do as they were told. On another occasion he poured petrol on a prisoner’s clothes, lit it and whipped the man round the crematorium yard until he ended up on the high tension barbed wire.

If he was in a good mood – as was normal with him when he was drunk with the joy of murder – Moll would shoot at the lighted end of a cigarette in a prisoner’s mouth. A wizard with the gun, he used even to shoot behind him with the aid of a mirror. He was quite indifferent whether his victims were Jews, Poles, Russians or even Germans. He was also responsible for carrying out the death sentence on his own people in the execution-room at the crematorium – SS men, soldiers from the front and civilian employees. Some executions were performed by poisonous injections administered in the dissecting room.

The first Sonderkommando was composed of Slovak prisoners who had an exceptionally vile task: to dig a mass grave for the rotting corpses gassed in the early primitive building, and burn them. They tried to escape from this desperate situation by taking flight, but their plans were betrayed.

On January 10th, 1943, they were told they were to leave Birkenau to go on a convoy, but when they reached Auschwitz I they were shot and burnt. Sick members of the squad, unable to go to Auschwitz on foot, together with personnel from the block, were shot at Birkenau by Rapportführer Palitsch, outside Block 2 in Camp BIb.

Shortly after Germany occupied Italy, in the summer of 1943, a group of 2000 interned American Jews was brought to Birkenau. They had been told that they were going to be sent to Switzerland to be exchanged for German prisoners, but instead they were sent to the gas chamber.

The overseer at the crematorium where the women were gassed was the infamous Rapportführer Schillinger. Among the group was a dancer named Horowitz. When Schillinger ordered her to take off her brassière, she suddenly snatched up her dress, threw it in the man’s face, seized his pistol and shot him in the stomach. She also wounded SS Emerich. Pandemonium broke out, in the course of which some of the SS threw away their rifles and fled. Ordered by the SS officers, prisoners of the Sonderkommando grabbed hold of the arms and drove the women back into the gas chamber. For this deed they were rewarded with better food rations.

The dramatic end of this convoy was the climax of a long story. The group consisted of extremely wealthy Polish Jews, led by a business magnate called Mazur. All had been issued with false American passports which had been obtained through the SS by the dancer mentioned above. Millions of dollars were paid out in this attempt to save their lives. Furnished with American passports, the group did in fact leave for Hamburg. They even embarked on a ship and stayed on it for some time. But the ship never left the harbour. The SS played out the game to the bitter end, using the period of enforced waiting in the harbour to obtain documentary letters from the ‘Americans’ for propaganda purposes. Meanwhile they continued to blackmail the relatives of their victims. Finally, when they had tapped all the available financial sources, they allowed the travellers to get under way. But the journey did not take them to America. Instead they all, without exception, went to Auschwitz – straight to the gas chamber.

This story of but one of the many convoys is typical evidence as to the real reasons for the Nazi campaigns against the Jews: money and property. The greater the wealth of their victims, the more the Nazis were attracted – and they stopped at nothing.