“Justice” at Nuremberg

Book Excerpt from "Streicher, Rosenberg, and the Jews"

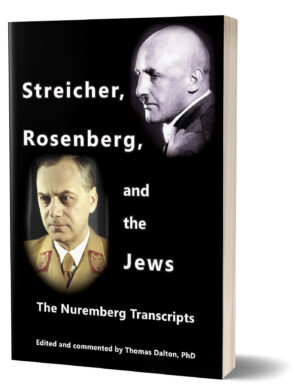

Thomas Dalton has had it with the Jews, so he keeps on dishing it out. His latest book on this topic titled Streicher, Rosenberg, and the Jews was a “quickie” in terms of how fast it was put together, since it is based mainly on the transcripts of the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal of 1945/46. As Dalton writes on the back cover of his book:

“If we want to understand the origins of the current mainstream narrative on the Holocaust, we need to go back to the beginnings to the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. During that trial, the ‘Jewish Question’ took center stage for the defendants Alfred Rosenberg and Julius Streicher. Here is a critically commented look into how the prosecution and the defense argued their cases.”

Thomas Dalton, Streicher, Rosenberg, and the Jews: The Nuremberg Transcripts, Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield, 2020, 314 pages, 6”×9” paperback, bibliography, index, ISBN: 978-1-59148-249-9. The current edition of this work can be purchased as print or eBook from Armreg Ltd. at https://armreg.co.uk/product/streicher-rosenberg-and-the-jews-the-nuremberg-transcripts/.

This article features the book’s first of twelve chapters. References in text and footnotes to literature point to the book’s bibliography, which is not included in this excerpt.

On 30 April 1945, with enemy forces closing in on all sides, Adolf Hitler took his own life. The next day, his second-in-command, Joseph Goebbels, did the same. Thus ended the grand 12-year German experiment with National Socialism – a period that witnessed a defeated, demoralized, and economically ruined nation rise to the heights of global power and prestige, only to be crushed by the combined forces of the largest militaries in the world. Hitler’s visionary idealism had proven so successful, for so long, that it evoked the enmity of France, the UK, the US and the Soviet Union. His actions against European Jews provoked global Jewry to conspire in his defeat.

And even though Jewry won that battle, Hitler and Germany’s National Socialism left the world with a social blueprint for success: a system by which native peoples everywhere might cast off pernicious influences, celebrate their own nationhood, and strive toward greatness. Despite Germany’s defeat, the long-term effects of Hitler’s system have yet to be revealed. The consequences are still being played out. In a larger sense, the war goes on.

Upon the formal end of the war on May 8, the four major Allied powers – the UK, France, the US and the Soviet Union – proceeded to partition and occupy Germany and Austria. The Soviets took control of what would become East Germany, the Americans occupied most of the south, the UK the north, and France took control of two large regions of southwest Germany. The foreigners retained absolute power for some five years, until the nations of West Germany and East Germany were established in 1949. The two sides reunified in 1990, restoring Germany to a single nation, but the invaders never left; to this day, there are nearly 40,000 American troops stationed in that country.

Upon the formal end of the war on May 8, the four major Allied powers – the UK, France, the US and the Soviet Union – proceeded to partition and occupy Germany and Austria. The Soviets took control of what would become East Germany, the Americans occupied most of the south, the UK the north, and France took control of two large regions of southwest Germany. The foreigners retained absolute power for some five years, until the nations of West Germany and East Germany were established in 1949. The two sides reunified in 1990, restoring Germany to a single nation, but the invaders never left; to this day, there are nearly 40,000 American troops stationed in that country.

Along with efforts to secure the peace and look after the immediate needs of civilians and displaced persons, the postwar occupying powers quickly began the process of hunting down and arresting anyone formerly in positions of influence in the Nazi government. Then, within a matter of months, the occupiers initiated an extensive and lengthy series of “war-crime trials” against their captives. But these were unlike any trials ever seen before. There was no precedent. No “civil law” could be applied because the alleged crimes were international in scope, and the alleged perpetrators were citizens of a polity – National Socialist Germany – that no longer existed. The Allies were effectively absolute powers, establishing any rules or procedures that they saw fit.

And we must bear in mind: they were the victors. They were no neutral parties; they were belligerent and hostile forces, the very same ones that had just expended so much blood and treasure on the battlefield to defeat the very men now on trial. And they had complete control. They were, quite literally, judge, jury and executioner. This was in no sense an objective and dispassionate process. There was no real quest for any truth. Guilt was the pre-determined outcome, and all proceedings aimed at that end.[1] Furthermore, there was no functional right of appeal. All verdicts were permanently and irrevocably binding. The victors set the rules, and the victors had the final say.

But the first step, as mentioned, was to bring the guilty parties into custody. In the Nazi hierarchy, the “big five” were Hitler, Goebbels, Heinrich Himmler, Hermann Göring, and Martin Bormann. Of these, the first two were already dead as of May 1. Bormann was soon to follow; he apparently committed suicide by leaping off a bridge on May 2, although his body was not confirmed at the time, and rumors of his survival and escape persisted for many years, until his buried corpse was unearthed in 1972. Himmler was arrested on May 21 and held by British authorities, but committed suicide two days later via a cyanide pellet hidden in his mouth, or so his British captors claimed. The only surviving member of this ruling caste was Göring, who was captured by the Americans on May 6. Consequently, he was the only one of the Big Five to sit under judgment at Nuremberg.

Over time, hundreds of former Nazi officers and party functionaries were arrested, by all four Allied powers. The Powers were anxious to assert their authority and mete out so-called justice to the captive Germans, thus confirming and finalizing their military conquest. Most importantly, trials would allow the Allies to “prove” to the world the evil nature of the Nazis and their absolute guilt in the war – and especially to document their malicious war against the innocent and beleaguered Jews. Stories of German atrocities against the Jews had been in the popular press for years, at least since August 1941, but there had been no real proof. Now, with the looming trials of actual German leaders, the Allies could prove to the world that such stories were true, that the Germans were the evil monsters that the Jews had said they were, and that no punishment could be too harsh. The extent to which they succeeded will be assessed in the text to follow.

The intent to hold military tribunals began in earnest already in late 1943, as eventual German defeat became more apparent. The Moscow Declarations were four statements signed by the Big Four powers in October of that year that declared an intent to prosecute leading Germans after the war. By April 1945, it was decided that each occupying power would initiate its own series of trials in their respective territories, and furthermore, that the Allies would jointly conduct one international tribunal at Nuremberg, to begin in November of that year. The joint trial would be called the International Military Tribunal, or IMT, and it would serve to prosecute the highest-ranking Nazis captured. It would run for one full year, from November 1945 to October 1946. It was also agreed that the Americans would later conduct another set of 12 Nuremberg trials, independent from the IMT; these would come to be called the subsequent “Nuremberg Military Trials” or NMTs. The NMTs began in December 1946 and weren’t completed until April 1949.

With all the big names, though, the IMT was clearly the star of the whole show, and it is the focus of the present study. The subsequent 12 NMTs got far less attention, and today are rarely cited in the literature.[2] But as mentioned, there were yet more trials conducted, by all four major powers, in their respective zones of control; some of these began even before the IMT. The Majdanek Trial, for example, was initiated already in November of 1944; the Chelmno Trial in May 1945; and the Belsen Trial in September 1945. On the other hand, the initial Auschwitz Trial – held in Poland, and conducted uniquely by Polish authorities – did not commence until much later, in November 1947.

And then there were the Dachau Trials. Running contemporaneously with the IMT, this American-led effort was itself a massive undertaking: a series of 465 separate trials over two full years, trying a total of some 1200 defendants. It was so complex that it had to be organized into a number of sub-trials; there was the main Dachau Camp Trial, along with dedicated trials for camps at Mauthausen, Flossenbürg, Buchenwald, Mühldorf and Dora-Nordhausen. All told, these resulted in around 115 death sentences.

Clearly, a huge amount of work was put into all these trials. Clearly, they served a vital purpose for the victorious Allies.

The Structure of the IMT

By mid-1946, the Allies had designated 24 men, among the hundreds captured, as “major war criminals”; these would be subject to the IMT’s unprecedented brand of justice. Of the 24, the two highest-ranking men were Göring and Bormann – the former being captured in May, and the latter, missing but believed to be alive, tried in absentia. The remaining 22 men, all held in custody, were as follows:

- Karl Dönitz, head of the Kriegsmarine (German Navy).

- Hans Frank, head of the General Government in occupied Poland.

- Wilhelm Frick, Minister of the Interior.

- Hans Fritzsche, popular radio commentator and head of the Nazi news division.

- Walther Funk, Minister of Economics.

- Rudolf Hess, Hitler‘s Deputy.

- Alfred Jodl, Wehrmacht Generaloberst.

- Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Chief of Reichssicherheits-Hauptamt (RSHA; Germany’s Department of Homeland Security) and highest-ranking SS leader to be tried.

- Wilhelm Keitel, head of the Wehrmacht’s Oberkommando (Supreme Command).

- Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, major industrialist.

- Robert Ley, head of Deutsche Arbeitsfront (DAF; German Labor Front).

- Baron Konstantin von Neurath, Minister of Foreign Affairs.

- Franz von Papen, Chancellor of Germany in 1932 and Vice-Chancellor in 1933–34.

- Erich Raeder, Commander in Chief of the Kriegsmarine.

- Joachim von Ribbentrop, Ambassador-Plenipotentiary 1935–36.

- Alfred Rosenberg, leading racial theorist and Minister of the Eastern Occupied Territories.

- Fritz Sauckel, Gauleiter (district leader) of Thuringia.

- Hjalmar Schacht, prominent banker and economist.

- Baldur von Schirach, Head of the Hitler Youth from 1933–40 and Gauleiter of Vienna.

- Arthur Seyss-Inquart, Reichskommissar of the occupied Netherlands.

- Albert Speer, architect, and Minister of Armaments.

- Julius Streicher, Gauleiter of Franconia and publisher of the weekly tabloid newpaper Der Stürmer.

From the perspective of the Holocaust and the German response to the Jewish Question, the two most important figures here are Rosenberg and Streicher; hence their testimony is featured in the present work.

The defendants would face four charges:

- Conspiring to commit crimes against peace

- Waging wars of aggression

- Committing war crimes

- Committing crimes against humanity

Each man could be charged with any one, or any combination, of all four counts. Twelve men were in fact indicted on all four counts. Verdict would then be rendered for each man on each individual count. A guilty verdict on even one count was sufficient for the death penalty – as was the case with Streicher.

In order to implement the tribunal, each of the four powers would supply one judge and one leading prosecutor, along with a support team of many individuals. These leading men were as follows:

| Judge | Lead Prosecutor | |

|---|---|---|

| Britain: | Geoffrey Lawrence | Hartley Shawcross |

| US: | Francis Biddle | Robert Jackson |

| France: | Henri de Vabres | François de Menthon |

| USSR: | Iona Nikitchenko | Roman Rudenko |

British Judge Lawrence would also serve as president of the IMT. It was said that a Briton as head of the proceedings would help to refute the widespread belief that the Americans were the driving force behind the tribunal. The American team was extensive, and included such men as Telford Taylor, Thomas J. Dodd, William Walsh, and Walter Brudno.[3] On the British side, Shawcross was supported by David Maxwell-Fyfe, John Wheeler-Bennett and Mervyn Griffith-Jones.

Notable, though, was the extensive Jewish presence on both the American and British teams from the very beginning. Roosevelt‘s close confidant Samuel Rosenman “crafted… the founding document of the IMT,” together with Jackson.[4] British Jews at the trial itself included Maxwell-Fyfe, Benjamin Kaplan, Murray Bernays, David Marcus and Hersh Lauterpacht. Jewish-American prosecutors or advisors were far more numerous; they included William Kaplan, Richard Sonnenfeldt, Randolph Newman, Raphael Lemkin, Sidney Alderman, Benjamin Ferencz, Robert Kempner, Cecilia Goetz, Ralph Goodman, Gustav Gilbert, Leon Goldensohn, Siegfried Ramler, Hannah Wartenberg and Hedy Epstein. Other likely Jews, on either the IMT or NMT American teams, include Morris Amchan, Mary Kaufman, Emanuel Minskoff, Henry Birnbaum, Esther Glasman, Moriz Kandel, Max Frankenberg, Alfred Lewinson and Elvira Raphael. And this is not to mention such men as Fritz Bauer, a German Jew who led the prosecution in the Auschwitz trials of the early 1960s.

Perhaps for good reason, it is difficult to get complete lists of team members, and even harder to determine which ones are Jews. And even a list of Jewish names, even a lengthy one, does not determine relative presence. Perhaps, then, we should take the word of someone who was there: Thomas Dodd. A non-Jew, Dodd was taken aback by the remarkable Jewish role at Nuremberg. In a letter to his wife of 20 September 1945, he explains his concerns about Jewish dominance:

“The staff continues to grow every day. Col. [Benjamin] Kaplan is now here, as a mate, I assume, for Commander [William] Kaplan. Dr. [Randolph] Newman has arrived and I do not know how many more. It is all a silly business – but ‘silly’ really isn’t the right word. One would expect that some of these people would have sense enough to put an end to this kind of a parade. [… Y]ou will understand when I tell you that this staff is about 75% Jewish.” (2007: 135)

An amazing claim, in fact. Given the lack of specifics, we can assume he was making an off-the-cuff assessment. But even as a subjective estimate, if, say, more than two-thirds of the American staff were Jews, it becomes an astonishing indictment of the fairness and objectivity of the trials – not to mention what it says about the power of a Jewish Lobby that could produce such presence. Dodd clearly felt that this undermined the integrity of the trials:

“[T]he Jews should stay away from this trial – for their own sake. For – mark this well – the charge ‘a war for the Jews’ is still being made, and in the post-war years it will be made again and again. The too-large percentage of Jewish men and women here will be cited as proof of this charge. Sometimes it seems that the Jews will never learn about these things. They seem intent on bringing new difficulties down on their own heads. I do not like to write about this matter… but I am disturbed about it. They are pushing and crowding and competing with each other, and with everyone else. They will try the case I guess.”[5] (135f.)

Understandably, not all present-day observers are happy with this statement. Jewish scholar Laura Jockusch (2012: 117) states that “Dodd‘s assessment of the Jewish presence at the IMT was not only exaggerated but certainly also biased.” In typical fashion, however, she offers neither argument nor data to back up her claim. Her immediate concession is revealing: “there were indeed dozens of Jewish lawyers and officials who assisted in the preparation of the trial.” So: Who decided it was appropriate to have “dozens” of Jews on the prosecution? Who believed that anything like 75% representation was acceptable, from a nation that has, at best, 2% Jews? And why?

Then there were structural problems – not the least being that the trials lacked such inconvenient features as “innocent until proven guilty.” The very nature of the IMT demanded relatively rapid verdicts for a large number of people, which effectively prohibited time-consuming but essential phases of evidence-collection and refutation, on-site visits, expert reports, and the like. Time-cutting measures were integrated into the very rules of the IMT. Article 19, for example, states: “The Tribunal shall not be bound by technical rules of evidence. It shall adopt and apply to the greatest possible extent expeditious and non-technical procedure, and shall admit any evidence which it deems to have probative value”.[6] In other words, testimony did not have to be confirmed with material or forensic evidence. The IMT could accept virtually any statement as fact: opinion, hearsay, rumor, inference, belief. The top priority seems to have been “expeditiousness.”

Furthermore, any facts that the court chose to take as “common knowledge,” no matter how they were obtained or how improbable they were, required no proof or evidence at all. This was known as “judicial notice.” Hence we have Article 21: “The Tribunal shall not require proof of facts of common knowledge, but shall take judicial notice thereof”.6 Once the court has taken judicial notice of something, it stands as an established fact and cannot be challenged. If the defendant should happen to disagree, he has no recourse. If the court “judicially notices” the homicidal gas chambers, or the 6-million death figure, then it becomes unquestionable in the courtroom. This was true in 1947, and it is still true today. Modern courts, particularly in Europe, will “judicially notice” that 6 million Jews died at the hands of the Nazis. Consequently, anyone charged with Holocaust denial cannot even challenge this point in his own defense. And if his lawyer raises the issue, he or she will in turn be charged with ‘denial’ – a remarkable situation, to say the least.

“A Maelstrom of Incompetence”

Yet another major problem – unsurprising in retrospect – is that many of the German defendant testimonies and affidavits were obtained under terrible conditions of duress or torture. This was true of all trials and was performed at the hands of all four Allies. After conducting extensive research in multiple original German sources, Germar Rudolf concludes:

“In many and pervasive respects, the conduct of the IMT was shockingly similar to that of the [other] trials. […numerous researchers] recount threats of all kinds, of psychological torture, of non-stop interrogation and of confiscation of the property of defendants as well as of coerced witnesses. Intimidation, imprisonment, legal prosecution, and other means of coercion were applied to witnesses for the defense; distorted affidavits, documents, and synchronized translations; arbitrary refusal to hear evidence, confiscation of documents, and the refusal to grant the defense access to documents; as well as to the systematic obstruction of the defense by the prosecution such as, for example, making it impossible for the defense to travel abroad in order to locate defense witnesses, or censoring their mail.” (Rudolf 2019: 96-97)

In 2013, British journalist Ian Cobain published an enlightening book, Cruel Britannia, which highlighted, for the first time since the war, a number of abuses during Nuremberg. The book focused on a detention center in central London known as the “London Cage.” As he explains in a 2012 article, it was “a torture center that the British military operated throughout the 1940s,” and in complete secrecy. “Thousands of Germans passed through the unit,” he says; many were beaten, sleep-deprived, held in stress positions for days at a time, threatened with murder, starved, hair ripped out. Another such facility, “Camp 020,” kept prisoners in either total light or total dark for days at a time, subjected to “mock executions,” or “left naked for months at a time.” Camp leaders “experimented in techniques of torment that left few marks” – no incriminating evidence that way. Centers at Bad Nenndorf and Minden in Germany subjected inmates to extreme cold, starvation and random beatings.

Of greatest concern in all this, apart from the humanitarian abuses, was the fact that

“after the war, interrogators switched from extracting military intelligence to securing convictions for war crimes. Of 3,573 prisoners who passed through [the Cage], more than 1,000 were persuaded to sign a confession or give a witness statement for use in war crimes prosecutions”

– exactly the situation described by Rudolf above.[7] Historian Stephen Howe summed up the situation: “a horribly repetitive picture… of British governments and their agents using systematic brutality… and then lying about it all”.[8] Suffice it to say that virtually any statement, on any topic, could be obtained from the captive Germans under such conditions.

And it is clear that the Allies did extract key statements this way from central German witnesses. Rudolf (2019: 93) describes the situation of the former Auschwitz commandant, Rudolf Höss, in the Minden Prison:[9]

“This torture was not only mentioned by Höss himself in his autobiography, but has also been confirmed by one of his torturers who, rather as an aside, also mentioned the torture of Hans Frank in Minden. And further, in his testimony before the IMT, Oswald Pohl reported that similar methods were used in Bad Nenndorf and that this was how his own affidavit had been obtained. The example of Höss is especially important since his statement was used at the IMT as the confession of a perpetrator, to prove the mass murder of the Jews.”

These, then, were the circumstances surrounding the famous IMT – highly problematic procedures, criminal actions against helpless detainees, and “confessions” obtained under the worst conditions imaginable. Little surprise that it found prominent critics, even among Westerners. American jurist Harlan Fiske Stone served on the US Supreme Court from 1926 until his death in 1946. In his final year, he famously referred to the situation as “a high-grade lynching party in Nuremberg” (in Mason 1956: 716). He was not speaking metaphorically. Ten of the 23 men, including Streicher and Rosenberg, were ultimately executed by hanging.

Then consider the comments of one American judge, Charles Wennerstrum, who presided over the seventh of the 12 later NMT trials, the “Hostages Trial.” Wennerstrum stated the obvious: “The victor in any war is not the best judge of the war crime guilt.” The whole system was “devoted to whitewashing the allies and placing sole blame for World War II upon Germany.” Trial proceedings were fundamentally biased. “The prosecution has failed to maintain objectivity aloof from vindictiveness, aloof from personal ambitions for convictions… The entire atmosphere is unwholesome,” he added. Most troubling was the use of highly questionable testimony from captive Germans:

“[A]bhorrent to the American sense of justice is the prosecution’s reliance upon self-incriminating statements made by the defendants while prisoners for more than 2½ years, and repeated interrogation without presence of counsel.”

Today such testimony would be utterly inadmissible in court; back then, it was standard procedure. Upon packing up to return to America, Wennerstrum remarked, “If I had known seven months ago what I know today, I would never have come”.[10]

And then we have the reflections of lawyer and US senator from Ohio Robert Taft (and son of William H. Taft, 27th President of the US). Though not directly involved in the trials, Taft took a sincere interest in events happening in postwar Europe, and he was generally appalled at the brutality and harshness of the victorious Allies. Just after the conclusion of the IMT on 1 October 1946, Taft gave a speech at Kenyon College in Ohio in which he pointedly condemned US actions: “Our treatment has been harsh in the American Zone as a deliberate matter of government policy, and has offended Americans who saw it and felt that it was completely at variance with American instincts.” He then offered a stinging indictment of the entire trial process based primarily on the principle that one cannot, after the fact, create laws by which individuals can then be prosecuted:

“I believe that most Americans view with discomfort the war trials which have just been concluded in Germany and are proceeding in Japan. They violate that fundamental principle of American law that a man cannot be tried under an ex post facto statute. The hanging of the 11 men convicted at Nuremberg will be a blot on the American record which we shall long regret.

The trial of the vanquished by the victors cannot be impartial, no matter how it is hedged about with the forms of justice. I question whether the hanging of those who, however despicable, were the leaders of the German people, will ever discourage the making of aggressive war, for no one makes aggressive war unless he expects to win. About this whole judgment there is the spirit of vengeance, and vengeance is seldom justice.” (Papers of Robert A. Taft, Vol. 3: 2003: 200)

Topping it all off were charges of gross ineffectiveness and blatant ineptitude. Dodd wrote:

“At least 150 [individuals here] are superfluous and worse. [… T]here is not one outstanding man in an important place in this organization – saving Jackson himself. I never saw anything as bad. [… T]his is a maelstrom of incompetence. It is awful.” (2007: 140-145)

One could hardly construct a harsher indictment.

Overall, we get a clear picture of a highly flawed and tendentious legal process, one aimed not at truth or justice but at revenge, punishment and ideological hegemony. For many years, this facet of the trial was downplayed or covered up. It simply did not look good to have the ‘morally superior’ Allies dispensing a brutal sort of mock-justice, even to the wicked Nazis. In the past decade, however, even conventional historians have come to admit the truth. The authoritative work International Prosecutors, for example, now has this to say:

“Nuremburg was part of a strategy of total war and total victory. To inverse Clausewitz, the IMT was the continuation of war by other means. The tribunal was intended to be a court of victors, not a forum of neutral parties or an imaginary ‘international community,’ and the trial was intended to be a ‘show trial.’” (Reydams and Wouters 2012: 15)

And again:

“Neither the Statute of the IMT nor the [IMT in the Far East] provides any safeguards at all to guarantee the independence of the prosecutor. Both [Nuremburg and Tokyo] tribunals were set up by the victorious parties to judge and punish the major war criminals of the defeated countries promptly, to dispense what is today rightly and commonly called ‘victor’s justice.’ Both were set up by occupying forces during occupation, and operated on the occupied territory of the defeated side. Both were highly criticized for lacking independence and impartiality, and both were ‘multinational but not international in the strict sense, as only the victors were represented.’” (Côté 2012: 372)

Yes, but this is only so much ancient history at this point; no lessons here for the present, surely – or so our historians would have us think.

But once again, this is obviously not just about history. Given that this whole event has direct bearing on the conventional Holocaust story – a story that is deployed repeatedly in the present day for highly consequential political ends – the trial demands a critical inquiry.

Documenting the Trials

Documentation on both the IMT and the NMT is extensive, and somewhat confusing. The full proceedings, mostly in the form of transcripts and documents submitted as evidence, were published shortly after the trials. Just the IMT documentation alone is impressive; in hard-copy format, it comprises 42 volumes, each running to 500 or 600 pages. Only the largest research universities have actual copies, but fortunately it is now available for free online. The work, published in 1947, appears under two titles: The Trial of German Major War Criminals, and Trial of the Major War Criminals before the IMT. It is also referred to as the “Blue Series” or the “Blue Set” due to the blue cloth these 1947 volumes were bound with. The full series is online at the US Library of Congress website:

(www.loc.gov/rr/frd/Military_Law/NT_major-war-criminals.html).

Additionally, Yale Law School has published text versions – unfortunately with many typographical errors – of the first 22 volumes, as part of their “Avalon Project”:

(https://avalon.law.yale.edu/subject_menus /imt.asp).

The 12 trials of the NMT, formally titled Trials of War Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals, are published as a 15-volume set and known as the “Green Series” (green cloth used for binding). Again, the full set is found at the Library of Congress site:

(www.loc.gov/rr/frd/Military_Law/NTs_war-criminals.html).

Finally, there is the 10-volume work called Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression. This set, also known as the “Red Series,” contains English translations of many of the German documents included in the full 42-volume IMT set. It can be found at:

(www.loc.gov/rr/frd/Military_Law/NT_Nazi-conspiracy.html).

And the first four volumes, in text form, are on the Yale website listed above.[11]

Needless to say, it can take a lot of searching to find the relevant material among the thousands of pages. The present work intends to contribute to a clearer illumination of the Jewish aspect of the trials.

The Core of Holocaust Revisionism

As stated, the present book is important primarily because of its contribution to our understanding of the Holocaust. As it happens, we have two fundamentally conflicting versions of that event. On the one hand, there is the standard, conventional, orthodox account: the intent by Hitler and the leading Nazis to kill every Jew in Europe, the gas chambers, the mass graves, the 6 million Jewish fatalities. This version is well-known because it is presented in countless ways, small and large: in schools, in text books, in films, in news stories, in governmental policy. And indeed, for most people in the Western industrial nations, this version of the story is almost inescapable. On the other hand, we have a competing view known as Holocaust revisionism. It’s worthwhile reviewing a few of the basics of each perspective.

First the conventional view: According to the experts, the plan to exterminate the German Jews was only hinted at prior to 1941. Then, upon the attack on the Soviet Union in June of that year, Germany allegedly began a process of mass-shooting of Jews behind the Eastern Front, by special units known as the Einsatzgruppen (‘task groups’). These troops, we are told, eventually killed some 1.5 million Jews. Also beginning in 1941 was the mass ghettoization of Jews, mostly in Poland. Through various means of deprivation, disease and oppression, the Nazis allegedly managed to kill another 1 million Jews in these ghettos by the end of the war.

The third main category of deaths, and the most notorious, occurred in the so-called extermination camps. Despite the fact that the Germans had hundreds of concentration camps, labor camps and related facilities, our experts tell us that mass killing occurred in only six camps: Auschwitz, Treblinka, Sobibór, Belzec, Chełmno and Majdanek. At the horrific center of these camps were the gas chambers: specialized, purpose-built facilities for the mass murder of Jews. Some of the gassing, such as at Auschwitz, allegedly occurred via cyanide gas (packaged as “Zyklon B”), but other camps, like Treblinka, supposedly used carbon-monoxide gas produced from diesel engines. Unfortunately, our experts cannot quite agree on exactly how the gassing procedure worked, nor how many Jews were killed in the chambers. Approximate present-day (traditionalist) consensus figures for each of the six camps are as follows:

| Camp | Jews killed | Method of gassing |

|---|---|---|

| Auschwitz | 1,000,000 | cyanide gas |

| Treblinka | 900,000 | carbon monoxide |

| Belzec | 550,000 | carbon monoxide |

| Chełmno | 250,000 | carbon monoxide |

| Sobibór | 225,000 | carbon monoxide |

| Majdanek | 75,000 | carbon monoxide + cyanide |

In sum, based on all three categories of killing (ghettos, shootings, camps), some 6 million Jews allegedly perished at the hands of the Nazis.

Holocaust revisionism, by contrast, challenges major aspects of the traditional account. As with the other view, there is some disagreement among specialists, but there seems to be a broad consensus on the following points:

- Hitler did indeed dislike the Jews, and strongly desired to rid Germany of them. This desire was shared by most of the top Nazi leadership. Their antipathy had three sources: (1) Jewish domination of major sectors of German finance, trade, media, the judiciary and cultural life; (2) the Jewish role in the treasonous November Revolution at the end of World War I; and (3) the prominent Jewish role in Soviet Bolshevism, which was seen by most Germans as a mortal threat.

- To achieve their goal, the Nazis implemented various means, including evacuations, deportations and forced resettlement. Their main objective was to remove the Jews, not kill them. Hence their primary goal was one of ethnic cleansing, not genocide. This is why no one has ever found a Hitler order to exterminate the Jews.

- Of course, many Jews would likely die in the process, but this is an inevitable consequence of ethnic cleansings generally.

- The Germans actively sought places to send the Jews. Proposed destinations included Siberia, central Africa and most notably Madagascar.

- By mid-1941, due to speedy victories in the Soviet Union, large areas of territory came under German control, and hence a new option emerged – the Jews would be shipped to the East.

- After late 1942, things were turning against the Germans. Shipments to the East were no longer viable, and furthermore all available manpower was needed to support the war effort. Thus deportations became subordinated to forced labor – hence the heavy reliance on Auschwitz, which was first and foremost a labor camp.

- A major problem with deporting and interning large numbers of Jews was disease, especially typhus. Therefore, a major effort was needed to kill the disease-bearing lice that clung to bodies and clothing. All Nazi camps were thus equipped to delouse and disinfest thousands of people.

- The primary means for killing lice was in ‘gas chambers,’ in which clothing, bedding and personal items were exposed to hot air, steam or cyanide gas. The gas chambers described by witnesses really did exist – but each one was built and operated as a disinfesting chamber, not as a homicidal gas chamber.

- The larger part of witness testimonies – both from former (Jewish) inmates and from captured Germans – consists of rumor, hearsay, exaggeration or outright falsehood. This does not mean that entire testimonies are invalid, but only that specific claims must be verified by scientific methods before we should accept them. In particular, claims about huge casualty figures, mass burials and burnings as well as murder with diesel exhaust are largely discredited.

- The total number of Jewish deaths at the hands of the Nazis – the ‘six million’ number – is highly exaggerated. The actual death toll was perhaps 10 percent of this figure: on the order of 500,000.[12]

Individual revisionists place emphasis on different aspects of the above account, but all would likely agree with all these points. Notably, not a single serious revisionist claims that the Holocaust “never happened.” This is a red herring that shows up repeatedly in the words of our traditionalist defenders. The claim is pure nonsense. Everyone agrees that something bad “happened” to the Jews; they simply disagree on the means and the extent of the suffering, along with the actions and intentions of the perpetrators.

In retrospect, it hardly seems controversial. This could well be seen as one more obscure debate among historians about events occurring some 80 years ago. And yet, traditionalists don’t see it that way. In fact, they view revisionists as a mortal threat. Keepers of the orthodoxy spare no means to suppress, censor and harass revisionists; they pull any strings necessary, and expend any amount of money, to make sure that the public never hears about this debate. By all accounts, they have something very important to hide.

In the present context, we will see that the Nuremberg trials, and especially the IMT, laid the groundwork for the entire Holocaust story. All the key elements appeared in those trials. And most of these were challenged by a few knowledgeable Germans in the process of their own defense. Of special interest are the defenses of Alfred Rosenberg and Julius Streicher; they gave extended testimony on many aspects of the Jewish Question, and their remarks are highly revealing.

Of course, their statements come with a few caveats. First, as described above, all Germans were held captive for months prior to the start of the trial, and were subjected to unknown degrees of duress, psychological pressure, coercion and outright torture. Second, they were obviously defending themselves in a legal process that could well lead to their deaths; they were surely highly motivated to exonerate themselves, disavow any involvement in mass killings, and to cast all blame onto others. And yet, many facts were apparent to all, and outright lies would likely have been useless – unless the lies were favorable to the prosecution, in which case they would pass unchallenged. In the end, we have to treat the words of Streicher, Rosenberg and the other Germans with the same skeptical stance that we would with any witness in a trial.

Even so, their remarks turn out to be most enlightening. The comments by Rosenberg and Streicher are almost uniformly true and correct, to the best of our knowledge. Erroneous statements on their part are either honest mistakes or false interpretations based on bad information. In his testimony, Rudolf Höss made a number of obviously false statements, which may be attributed to coercion or perhaps even to deliberate falsification on his part, likely in response to torture and abuse; it may have been his way of signaling to the world the absurdity of his very “testimony.”

Textual Edits and Commentary

The text to follow is taken directly from the IMT documentation. Source information (volume and page number) is included for purposes of verification. However, a number of superficial edits have been made in order to improve readability and flow of argument. The prosecution made many redundant references to specific documents, for example, and these have been edited out. Passages on formalities or trivial issues, such as might arise in any trial, have been deleted. And lengthy passages that have minimal or no relation to the Jewish Question or the Holocaust have likewise been removed (and noted).

Importantly, at many points along the way, commentary has been added to explain, highlight or otherwise clarify statements made by either the prosecution or the defense. Such commentary has been set in bold font on a grey background to clearly distinguish it from the verbatim testimony.

In terms of the flow of the text, it is broadly chronological. Chapter Two opens with the general case against the Nazis with respect to Jewish persecution. Chapters Three and Four address Rosenberg: first the case against him, and then his own defense. Chapter Five then covers Rudolf Höss‘s testimony, which is so central to the modern Holocaust narrative. After this, we jump back in time (to January 1946) to give the case against Streicher in Chapter Six; Chapters Seven through Nine then move ahead (to April) to present his extended and detailed defense. Chapter Ten – dating from August 1946 – presents short closing statements by both Rosenberg and Streicher, along with a few relevant passages by other defendants. Chapter Eleven gives the verdicts and sentences, and the final chapter offers some concluding thoughts.

With this in mind, we now turn to the transcripts themselves.

* * *

The rest of the book can be read in the print and eBook versions as offered by Armreg Ltd. at https://armreg.co.uk/product/streicher-rosenberg-and-the-jews-the-nuremberg-transcripts/.

Endnotes

| [1] | British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden said, “the guilt is so black that they fall outside and go beyond the scope of any judicial process.” (in Reydams and Wouters 2012: 10). For Churchill‘s part, he wanted to simply identify the leading Nazis and have them “shot to death within six hours” (ibid.: 11). |

| [2] | The 12 trials were: Doctors’ Trial (9 December 1946 – 20 August 1947), Milch Trial (2 January – 14 April 1947), Judges’ Trial (5 March – 4 December 1947), Pohl Trial (8 April – 3 November 1947), Flick Trial (19 April – 22 December 1947), IG Farben Trial (27 August 1947 – 30 July 1948), Hostages Trial (8 July 1947 – 19 February 1948), RuSHA Trial (20 October 1947 – 10 March 1948), Einsatzgruppen Trial (29 September 1947 – 10 April 1948), Krupp Trial (8 December 1947 – 31 July 1948), Ministries Trial (6 January 1948 – 13 April 1949), and High Command Trial (30 December 1947 – 28 October 1948). In total, these tried around 1700 defendants, ultimately putting almost 200 to death. |

| [3] | “The total number of US employees… employed at Nuremburg may have reached 1,700” (Townsend 2012: 183). |

| [4] | Townsend (2012: 173-174). |

| [5] | And in fact, the Jewish Maxwell-Fyfe “emerged as the day-to-day courtroom leader of the prosecution as a whole” (Taylor 1992: 221). On the issue of “a war for the Jews,” the case for this was much stronger than even Dodd realized; see Dalton (2019). |

| [6] | IMT, Vol. 1: 15. |

| [7] | Quotations from Cobain‘s article “How Britain tortured Nazi POWs” (Daily Mail, 26 Oct 2012). See also Fry (2017). |

| [8] | S. Howe, “Review of Cruel Britannia” (Independent UK, 24 Nov 2012). |

| [9] | For Höss’s full testimony, see Chapter Five. |

| [10] | Chicago Daily Tribune (23 Feb 1948, p. 1). |

| [11] | To add to the confusion, the UK government published two further sets of the proceedings: (1) A condensed British version of the IMT, published under the same name as the US version, except in 23 volumes; and (2) A British version of the 12 NMT trials, published as Law Reports of Trials of War Criminals (14 volumes). These two sets are rarely cited in the literature. |

| [12] | For a more detailed account of Holocaust revisionism, the reader is recommended to see The Holocaust: An Introduction (Dalton 2016), Debating the Holocaust (Dalton 2020), or Lectures on the Holocaust (Rudolf 2017). More advanced readers may find value in Dissecting the Holocaust (Rudolf 2019b). For the full story, see the entire Holocaust Handbooks series, currently numbering 42 volumes [52 in June 2024; ed.] and addressing virtually every aspect of these events. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 2020, Vol. 12, No. 2; excerpt from Thomas Dalton, Streicher, Rosenberg, and the Jews: The Nuremberg Transcripts, Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield, 2020

Other contributors to this document:

Editor’s comments: