My Impressions of the New Russia

Is a 'National Socialist' Russia Emerging?

Ernst Zündel, a German-Canadian publisher and civil rights activist, lives in Toronto. Born in 1939 in southwest Germany, where he was raised, he migrated to Canada at the age of 19. He attracted international notoriety during the first and second “Holocaust trials” in Toronto, 1985 and 1988. In August 1992 Canada's Supreme Court declared unconstitutional the law under which he had been tried and convicted. For more about these trials, see the detailed work compiled by Barbara Kulaszka, Did Six Million Really Die?: Report of the Evidence in the Canadian “False News” Trial of Ernst Zündel. (This 572-page book, reviewed in the March-April 1995 Journal, is available from the IHR for $53, postpaid. [Check www.ihr.org for current availability and price; ed.])

This essay is adapted from Zündel's presentation at the Eleventh IHR Conference, September 1994.

For some time I had heard that all kinds of nationalist groups were springing to life in Russia, some of them with newspapers of fairly large circulation, and even one or two emblazoned with swastikas. After wondering, “What are these Russkies up to?”, I decided to go see for myself.

I first sent three colleagues to Russia as a fact-finding advance party. They made contacts, did the preliminary work, and came back with interesting tape-recorded interviews. I assessed these interviews and the other material they brought back. I was fascinated to see copies of Russian newspapers with swastikas on them, illustrated with lurid Jewish stars dripping with blood.

So, on August 5, 1994, five of us took off for Russia with an invitation in our pocket from Vladimir Zhirinovsky's Liberal Democratic Party, which is represented in the Russian parliament (Duma). We appreciated that his Party had booked several hotel rooms for us in Moscow, which are normally costly and not easy to get. Even for people from the West, Russia has become a very expensive country.

I arrived with my own interpreter, just in case, a man who speaks five languages. Because I wanted to be sure that what my own interpreter said was accurate, a second interpreter met me in Moscow – a Russian native and a writer by profession. I also brought along my own video cameraman, Jerry Neumann, as well as a photographer and a coordinator/troubleshooter.

Vladimir Zhirinovsky

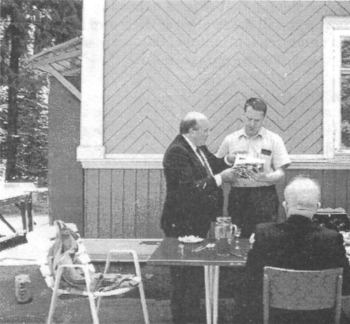

Within the first few days of our two-week stay in Russia, we met with Vladimir Zhirinovsky. He invited us for a private lunch at his dacha, his weekend retreat in the woods outside Moscow. Many of you perhaps saw him interviewed on the David Frost television show, when he talked about how all Russia will rejoice when he comes to power. Seeing this interview, you might think this guy is stark-raving mad, that he's a crazy buffoon.

Let me caution you, though. This man is not only a lawyer, he was perhaps the only human rights lawyer in the country during the final years of the Soviet regime. He never joined the Communist Party. When everyone else was still a loyal apparatchik, he worked as a human rights lawyer. Since his rise to prominence, stories in Russia's tabloid press have said that he was a KGB agent, that he worked for a Zionist organization called Shalom, that his father was Jewish, and so on. Such stories hurt him, not least because many Russians hate Jews with sometimes irrational passion. In today's Russia, calling someone a Jew can ruin his reputation.

I found that intelligent Russians suddenly got starry-eyed when the conversation turned to the Jewish question. One thing that Russians are absolutely wise to, and very sore about, is the role of Jewish revolutionaries in wreaking havoc in Russia during the first decades of this century. [See “The Jewish Role in the Bolshevik Revolution and Russia's Early Soviet Regime,” in the Jan.-Feb. 1994 Journal.]

Based on all my conversations during that visit, I make this prediction: The Russian people will one day take revenge for what has happened to them and their country over the last 70 years, frequently at the hands of Jewish Bolsheviks, and many innocent Jews are going to be hurt in the process. The Jews who are leaving the country to move to Tel Aviv, Toronto and New York are wise, because the anti-Soviet revolution in Russia is not yet over.

The upheaval I foresee in Russia won't be neat and orderly, as it was in Germany. It will be brutal and messy. If Boris Yeltsin and his government are not able to halt the country's economic deterioration and political instability, I predict massive anti-Jewish pogroms in Russia. And I mean massive. Many ordinary Russians blame the Jews for their present and past problems. There are still many Jews in very influential positions, and because there are many more Jews in Russia than statistics indicate, it's likely that there will be many more victims.

In conversations about Zhirinovsky since I returned from Russia, people have said to me, “Oh, he's half-Jewish” – as if that settles the matter. Some of my Russian contacts similarly said to me: “Oh, his name is Vladimir Wolfovich. He's a half-Jew.” Although the hostile media treats me as a firespewing anti-Semite, actually I have always been very cautious about judging people by labels or stereotypes. First of all, whoever Vladimir Zhirinovsky's father really might have been, only his mother really knows. Anyway, none of us can choose our father.

What's important is what this man has made of himself, and what he will do for Russia and, consequently, for the world. My own impression, based on a meeting for two hours over lunch, is this: Zhirinovsky is a highly intelligent, agile, flexible thinker. He is a clever tactician. Like me, he is a natural and accomplished publicity seeker. (After all, his birthday is April 25th, one day after mine. So it figures.)

He told me that because he was not a member of the Communist Party, and because the media in Russia was entirely in the hands of Communist apparatchiks, the only way he could get public attention was by creating publicity stunts, by grandstanding, by being outrageous, by saying things that he knew many Russians felt but never had the courage or opportunity to say.

Minority Nationalities

One of the main points that Zhirinovsky keeps making is that under Soviet rule the Communist leaders drained enormous energy and resources from white, Slavic Russia to build up the peripheral, non-Russian republics in the southern USSR, such as Uzbekistan, Tadzhikistan, Turkmenistan and those other southern republics. He attributes this policy to a cosmopolitan obsession in the Marxist ideology.

Zhirinovsky says that the Communist rulers did not allow the various nationalities to rise or fall to their proper cultural and economic standard. It was wrong, he says, to divert energy and resources from Slavic Russia to build opera houses, cultural centers, railroad stations, highways, and atomic power plants for these backward, non-Russian minority nationalities. The Soviet rulers tried to artificially raise these non-Slavic peoples – some of whom had been little more than nomadic sheep-herders – to the cultural and economic levels of the Russians. Instead of expending Russian sweat and treasure on them, says Zhirinovsky, these backward peoples should have been allowed to keep on tending their sheep. He often mentions that his own grandfather perished while building a Stalin-era railroad in Kazakhstan, and was buried far from home in the empty steppe.

What white, Slavic Russians said to me about these minority nationalities were very, very similar to the arguments I hear from white American nationalists about the minority racial and ethnic nationalities in the United States – about wasteful welfare payments to parasitic ghetto dwellers, and so on. Russians speak about non-Russians – about their lack of productivity and high birth rates – in the same way that white American speak of some racial minorities in the US. So, this is a sentiment that Slavic Russians share with many European Americans and western European nationalists.

Obstacles in Political Work

Will Zhirinovsky one day be president of Russia? I don't know. For one thing, his life is in constant danger. He is surrounded by security guards. It costs just $20 to get a man killed in Moscow. If you are a politician with bodyguards, it can cost $500. If you are really well guarded, like a banker or a well-to-do business man, it will cost $800. There are more guards employed by Russia's many private security firms than there are soldiers in the entire US Army.

Zhirinovsky explained to me that his party organization, in this vast country of Russia, is overstretched, understaffed and under-financed. Political organizers face all kinds of problems that we in the West can hardly relate to. Photocopiers, for example, are hardly known in Russia outside the major cities. Also, they don't have private print shops. If someone needs handbills for a political meeting, they have to turn to the former state and Communist Party-run print shops, which printed local newspapers, books, and so forth. Nearly everyone I spoke with asked for help. Above all, they asked for printing and duplicating equipment.

So the problems Russians face in building a democratic, self-governing society seem almost insurmountable. Still, Zhirinovsky and his party are better off than most because at least his office is computerized, with photocopiers and fax machines, and he has a very capable, multilingual staff.

I interviewed most of Zhirinovsky's important advisors. One is a former diplomat with the United Nations who spoke beautiful, accentless English. For eight years he was president of the Soviet United Nations Association.

Vladimir Zhironovsky.

Zhirinovsky's second in command is a retired Red Army general staff officer, a 17-year veteran named Kamerov. He is a well-mannered, handsome man who struck me as very capable and very efficient. (I spoke with him through an interpreter, because he doesn't speak any English. Incidentally, in all the nationalist political groups I visited, I encountered what seemed like an uncanny Red Army presence, nearly always former high-ranking officers.)

I also met and spoke with one of Zhirinovsky's foreign policy advisors. This man, who looks like Russia's last emperor, Tsar Nicholas II, had been a magazine publisher. In his magazine he made some rather nasty remarks about Zhirinovsky supposedly being Jewish. He also published a cartoon depicting Jews as hairy-legged, hairy-tailed rats. (Russians seem to like their anti-Semitism raw.) Well, a Jewish prosecutor in Moscow who understandably didn't like this derogatory, stereotypical depiction of Jews, charged the publisher under the equivalent of Canada's “hate laws,” and had him locked up. He spent four months in jail, where he suffered two heart attacks and was punched around a bit.

Well, the one man who publicly came to his defense, organizing demonstrations outside of the jail, was none other than Vladimir Zhirinovsky. He was also the only one to show up in the police court to defend him. Zhirinovsky and his supporters demanded freedom for this Russian dissident writer/publisher to state his mind, even though what he had done was distasteful. Zhirinovsky said he wanted freedom in Russia, that this was the new Russia, and so on.

So I asked this man who was, after all, freed from jail thanks to Zhirinovsky, “but you criticized him. How come you're now here?” He replied: “I couldn't find a job after coming out of jail, and Vladimir Zhirinovsky hired me, even knowing all those things about me.” And he added, plaintively: “I thought that was a very Christian act and a very Christian spirit.” That was his answer to my question: “Is Zhirinovsky a Jew or a half-Jew?”

Even though I give people the benefit of the doubt, I think that if I had been in Zhirinovsky's position, I would have thought twice before hiring a man like that. I know it's easy to be cynical about something like this, but I think that this was an act of principle. Zhirinovsky is a man who sincerely believes in human rights and who, therefore, fought for human rights. As a human rights activist myself, and as someone whose own human rights have been denied many times, I say, for the time being anyway: I'm with Zhirinovsky on this one.

I was surprised to learn that Zhirinovsky didn't have much “outreach” to the Russian masses. He has the outer trappings of a western politician, but apparently he has not reached out to the masses on a grass-roots level. Perhaps no one has advised him yet how populist political campaigning works on the ground.

Zhirinovsky seems to be trying to build a following from the top, largely through bluster and propaganda. Maybe it's just that, as he says, he doesn't have the means. As he puts it: “We have no middle class. We have no rich people, except Communist Party apparatchiks and gangsters. Where do I get financial support from? The little people, who have little to give?”

It was really something to see the support he gets from the “little people.” Volga fishermen would come in the door, shyly clutching some worn-out old rubles, getting their names written in the party registration book, getting their party card, and so on. It was very moving to be present in Russia to witness a few of these first, infant steps in such an obviously painstaking process of building a democratic society. I was very humbled and proud to be there at such a moment.

Another man I met was a good-looking, highly intelligent former KGB general named Alexander Sterligov who seemed to be in his late 50s. He had been the internal security advisor to former vice-president Aleksandr Rutskoi. He was sacked by the Yeltsin government because he advised Rutskoi that the Gorbachev-era reforms as well as the western-style policies adopted by Rutskoi and Yeltsin were unconstitutional and dishonorably betrayed Russian national interests. So Rutskoi and Yeltsin gave Sterligov a choice – either leave quietly with full honors, or be sacked with less than full honors and a cut in pension and privileges. He decided to leave quietly.

Sterligov still had some residual benefits from his KGB position. When I met him, he was surrounded by uniformed police or soldiers, he was protected with bulletproof glass, and his office was behind doors that electrically opened like bank vaults. Blue-eyed, well groomed and well mannered, Sterligov impressed me as extremely well-organized, no nonsense and businesslike. I am sure that he and capable men like him will be a force in whatever regime finally comes to power in Russia.

In addition to Zhirinovsky's almost mainstream party, there are many small and more radical political parties and groups. You can find their activists outside the Moscow subway entrances, selling their newspapers. And Russians buy these papers. They say that for each newspaper that's sold, ten persons will read the issue. They even buy and sell second-hand newspapers, which are often sent to Siberia and other distant places. Imagine that! You will always see Russians reading. Russia is one of the world's most literate nations. For a Russian a book is still a treasure.

I met another man named Ivanov, a very pro-German fellow who has written 25 books and booklets. As a result of Stalinist-type political prosecution, he was sent to a mental health facility in 1961, and then, in 1981, he was exiled to the Ural mountains region for three years. And yet, in spite of all that, he remained completely undaunted. I was very impressed.

Another very nationalistic Russian I met had been a diplomat with the United Nations who was still with the Russian foreign service, working in the Foreign Ministry in Moscow. Neither he, nor anyone else I spoke with, had any apology for the fact that they had been, at one time, part of the Soviet state apparatus of the Communist Party. I saw none of the disgusting groveling that Germans have been engaging in for the last 50 years – trying to apologize for or explain away employment in Hitler's government, membership in National Socialist Party formations or the SS, or even military service in the Wehrmacht.

At Zhirinovsky's dacha outside of Moscow, Ernst Zündel shows the Russian political leader a copy of Barbara Kulaszka's detailed book about the 1988 “Holocaust trial” in Toronto.

Patriotic Pride

Not a single Russian I met dishonors or defiles himself or his country. Veterans of the Red Army, for example, could and did accept criticism of the Soviet military. While hating Communism, and loathing the Jewish role in the Soviet regime, every one is proud of his service as a Red Army officer or soldier, and is loyal to his unit. Make no mistake about it: the Russian spirit of patriotism and nationalism is alive and very strong.

Eventually, I did find swastika-emblazoned newspapers in Moscow. I saw newspapers with front-page photographs of Dr. Goebbels speaking, with quotes from him coming from his mouth (in text bubbles), as well as quotations from Hitler, Alfred Rosenberg, Walter Darré, and other Third Reich personalities.

In my numerous discussions with Russian intellectuals and journalists about the Second World War and National Socialism, I was astonished by their knowledge. You really have to know your stuff, because they certainly do. I challenge any postwar, “modern” German Wirtschaftswunderling to visit Russia and take on the Russians about German history, because they would be defeated roundly. And no one should visit Russia expecting to meet Russians who will dump all over their own history. They don't and won't. Mindful of the contrast with today's Germans, I found this trait refreshing!

Stalin and Hider

Another big surprise for me was to learn that nationalist Russians, at least the ones I met and spoke with, put Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler on virtually the same level. Whereas we think of Stalin as a tyrant and murderous thug, the Russians speak of him with lots of nuance, shades of grey and many explanations. They regard Stalin as a stern ruler who brought backward Russia into the 20th century, who brought the downtrodden Russian masses, virtual serfs, into the modern world. Their fathers or grandfathers had told them how, because of Stalin, they could go to school for the first time, how they received modern medical services, and so on. Stalin made all that possible, they all told me.

In the Russian context today, nationalists regard Stalin almost as a National Socialist. There are many similarities between the policies of Stalin and Hitler, I was told. Each eliminated class barriers, elevated humble peasants and workers, and made it possible for ordinary people to become officers, professional people, university professors, and so forth.

When I piped up to ask, “but what about Stalin's persecutions?,” they would respond: “Oh, you mean of the Jews?” That ordinary Russians suffered terrible persecution, and were murdered by the millions under Stalin, well, that's unfortunate. But they were glad that he cleaned out many of the original Jewish Bolsheviks during the great “purges” of the 1930s, and replaced them with Slavic Russians. It's odd, but the Russians seem to be able to forgive Stalin for much of his brutality, while at the same time they can hold a deep and seemingly permanent grudge against the Jews who were around him, and who preceded him.

In numerous conversations, many Russians I spoke with regarded both Hitler and Stalin as tragic victims of history. Virtually to a man, they said that something must have happened – something that we still don't fully understand – to explain why Hitler went to war against Stalinist Russia. Everyone thought the German-Russian war was a great tragedy – a terrible mistake that should never have happened. Perhaps Russians spoke this way with me because I am a German and they wanted to build bridges. I don't know. Anyway, this view was a real surprise to me.

Russian 'Subhumans'?

Having been very anti-Communist all my life, and as one who is proud of Germany and the German record during the Second World War, you can imagine the heated discussions I had with these Russians.

Again and again a phrase came up in these talks, one phrase that really bothered the Russians with whom I spoke: Untermensch, “subhuman.” This very unfortunate term, which means something like subhuman scum, was used in early German wartime propaganda to describe the Soviets.

In every discussion between and Russians and Germans (and perhaps any Westerner), these things loomed large: the German invasion of Russia, Hitler's war against the Stalin regime, the Untermensch phrase, and Germans looking down on the Slavs as second-class Europeans. Naturally, I sensed in all this a revisionist opportunity. I thought to myself: Gee, this is nothing. We can solve these problems in a jiffy.

With regard to the Untermensch term, I said that it was simply stupid to call Russians subhumans. I couldn't help but think this as I talked with all these fine-looking examples of Aryan manhood. I might mention that every Russian I met with was, racially speaking, a beautiful specimen – two meters tall, with blue eyes and blond hair. Compared to them I looked like a short, second-rate runt.

They became very quiet when I told them:

Look, I understand your objection to the term Untermensch. I admit that this was a stupid propaganda slogan, but you should understand it in the context of the time, that it was based on the behavior of Bolshevik revolutionaries who did in fact behave like subhumans. So you should not feel bad about this. If you didn't behave like Untermenschen, this doesn't refer to you.

But also keep in mind all the woman who were raped across eastern and central Europe, all the people who were killed, all the personal belongings that were looted and destroyed, all the houses that were torched, and all the victims of the postwar Soviet-run camps in eastern and central Europe. That wasn't the work of nice people. It's why you got a bad reputation.

Hitler's Attack on Russia

Regarding Hitler's attack against the Soviet Union, I referred to Icebreaker: Who Started the Second World War?, the magnificent book by Russian historian Victor Suvorov [published in English in 1990]. Thank God for Suvorov and his work, I thought to myself. In Icebreaker, Suvorov [real name Vladimir Rezun] details how Stalin was preparing a massive military attack against Germany and the West, and how Hitler beat him to the punch by a mere two weeks in a preventive strike.

Well, was I in for a shock. In conversations and discussions, everyone of my Russian partners rejected Suvorov and his thesis out ofhand. I nearly fell off my chair. Here I played my trump card, and they rejected it flat. Why? Because Suvorov was a defector. Imagine that. (This senior Soviet military intelligence officer was granted political asylum in Britain.)

I responded:

This is irrational. Come on now. Let's reason this out together. You've told me that Communists were responsible for draining Slavic Russia's wealth and resources. You've said that the Gulag camp system, and so on, was their resposibility, and that all of you suffered one way or another at Soviet hands. And yet, you condemn the one Russian who had the nerve to leave his own country to bring to the world this news that Stalin was preparing in 1941 to attack, not just Germany, but all of western Europe.

At this point in the conversation an uneasy silence usually permeated the room. My Russian partners became even more silent when I played my second and third trump cards. I cited German or Austrian historians who had, before Suvorov, presented evidence in support of this same revisionist view. These include Erich Helmdach in his 1975 book, Überfall, Max Klüver in his 1986 book Präventivschlag 1941, and Ernst Topitsch in Stalins Krieg (1985) [published in English in 1987 by St. Martin's Press as Stalin's War]. The Russians responded by saying, apparently quite candidly, “Gee I'd be quite interested in looking into that” (referring to these non-Russian works).

I also found that sometimes, after further discussion, they would concede, “Oh yeah, we know that there were massive [Soviet] troop movements [in 1941] toward the west.” This was based on bits of information about the great military build up in 1941 they had heard from fathers, grandfathers, uncles and so forth.

So this is a great opportunity for revisionists. We can puncture the Allied (and especially Soviet) propaganda myth of insatiable, fire-spewing Nazis who attacked poor, innocent mother Russia. Even with our limited resources, we can detoxify the debate. We can remove this poison between the Germans and the Russians. In the process, we can liberate pent-up energies that could change the world.

Building a New Russia

The Russians I met and spoke with closely share my own view of the kind of society we would like a society based on pride in race, pride in nation, pride in culture. These Russians told me how fiercely they oppose the “New World Order.” They want nothing to do with it. What they want is a white Russia, a Slavic federation similar to the old Tsarist empire.

Vladimir Lenin addresses Red Army troops in Moscow, May 1920. Leon Trotsky (Lev Bronstein), who commanded the Bolshevik armed forces, stands to the right facing the camera. Behind him (partially obscured) is Lev Kamenev (Rosenfeld), another leading Jewish Bolshevik figure.

If those nationalist Russians ever shake off the Communist monkey that's still clinging to their back, and clean out the Communist apparatchiks who still permeate the Russian system like termites, the one path they certainly will not take is toward American-style capitalism.

Patriotic Russians are totally against the Americanization of their country. They fiercely resent what Coca Cola and McDonald's hamburgers mean for Russia. Yet these very same Russians I spoke with wore blue jeans and Nike running shoes, carrying Adidas duffel bags, and so on. When I pointed this out, they were a little embarrassed. But I said, “Okay, look. I'm just pointing this out to you. Not everything coming from the west is bad. Don't throw out the baby with the bath water. Don't be like Germans – extremists.” We had a good laugh about that.

Russia today is like Weimar Republic Germany in the aftermath of the First World War – humiliated, weak and disorganized, but still a great and racially homogenous nation. The historical comparisons are frightening. If the people I met with have anything to say about it, Russia will not adopt an economic system with the dog-eat-dog-style capitalism of the United States. Russians are instead likely to choose as their model a system that worked eminently well in Europe during the 1930s, something like the National Socialist regime that was adopted by Germany at a time when she was in somewhat the same condition as Russia today.

Even though Hitler attacked the Soviet Union, and many Russian families lost sons and fathers and grandfathers to the Germans in that war, Russians instinctively understand all this. That's why so many of them now study the writings of such men as Alfred Rosenberg and Adolf Hitler. In downtown Moscow I bought a Russian edition of Mein Kampf. It was a handsome copy, gold embossed with black linen cover. Any Russian can freely buy one. Just try that in Berlin, Vienna or even Toronto!

I believe that if we revisionists quickly get our act together, we can help free the Russians from some terrific misconceptions, and help them as they build a society that is compatible with their own traditions, and right for their own needs.

We have a wonderful opportunity here to heal old wounds. In the process, though, we will have to work together to overcome some of our own prejudices. Speaking for myself, I must deal with prejudices based on tales from my father about the very real wartime brutalities of the Bolsheviks and the Red Army across Europe, including mass rapes, looting, wanton cruelty, and so forth.

I'm telling you: watch Russia. We revisionists can have an influence on developments there, an impact far out of proportion to our numbers. We can help those people in adopting a civilized form of self-government. Much more than the Chase Manhattan Bank, we revisionists can truly help free Russia.

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 15, no. 5 (September/October 1995), pp. 2-8

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a