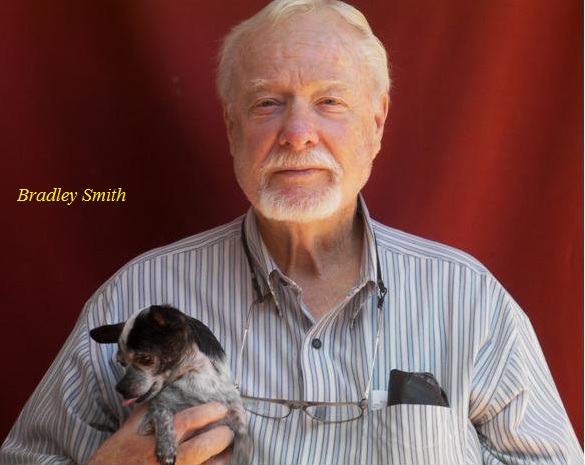

Remembering Bradley R. Smith

Editorial

On Thursday evening, 18 February 2016, I glanced at my email on my phone. The subject of a newly received message struck me like a lightning bolt. “Bradley RIP” was all it said. It wasn’t that it was entirely unexpected. Bradley had been ill for many years, fighting off heart ailments, cancer, and even a bullet to the head during the Korean War, but somehow it seemed that Bradley would always be among us.

I first became aware of Bradley in the late 1980s. I had discovered him a couple of years after my introduction to Holocaust revisionism. I knew of him through his book Confessions of a Holocaust Revisionist, and the work that he did for the Institute for Historical Review.

It was in late 1993 that an editorial appeared in the college newspaper of the university that I was attending – denouncing Smith’s “Campus Project.” I decided to pick up a few copies, cut out the story, and mail one off to Bradley. It was the beginning of a friendship that lasted for more than 20 years.

We worked together (along with Greg Raven and David Thomas) to put up one of the earliest revisionist websites back in the mid-90s (we referred to it as CODOHWeb at the time). As unlikely as it seemed, Bradley was always very quick to embrace new technology. He was always looking for a new way to storm the “castle wall.”

We would correspond back and forth nearly every day via email. And there were always those lively phone conversations. We could talk for hours it seemed. I remember asking Bradley questions about revisionism during those early years. He would tell me that he didn’t read revisionism any more and would spout off the title of some esoteric topic that had captured his attention. This week I turned to a chapter in his A Personal History of Moral Decay and smiled when coming upon a reference to his reading a book about the Sumerian alphabet. That was Bradley!

It surprises me, even now, that I met Bradley “face-to-face” only on one occasion, when we shared a room at David Irving’s first Real History Conference in Cincinnati back in 1999. It was a marvelous weekend with Bradley speaking on the subject of “Memory.” While the supposed target of the talk were Holocaust “eyewitnesses,” Bradley seemed challenged with his own memory. Was it an act? A writer’s joke? I thought it all quite funny, but noticed that our host David Irving seemed not at all amused.

Bradley was always coming up with new ideas. There were new advertisements, new books, new designs for the website, new websites. Most of the ideas never settled before new ones sprang up. But still, work got done. More work was accomplished to establish intellectual freedom on the Holocaust story than most ever even imagine.

In late 2014, I attempted to interview Bradley. We didn’t get very far.

“Widmann: You’ve tried your hand at many things throughout your life. I know you were in the army during the Korean War, you were a bookseller, a bull-fighter, and of course an activist for intellectual freedom with regard to the Holocaust debate. How would you like to be remembered?

Smith: It’s a matter that has never caught my attention. Memory itself, however—I’m very interested in memory. As a writer, I am essentially a failed autobiographer. It’s all about memory. My own. When my memory dies, along with the rest of me, you can imagine what will happen with regard to my attention to the memories of others.”

Bradley was denounced by many. Several such derogatory quotes appeared on the back cover of his Confessions of a Holocaust Revisionist Second Enlarged Edition. Alan Dershowitz called him a “known anti-Semite and an anti-Black racist.” Others called him even worse. Beneath these foul slurs Bradley placed a quote about himself “a swell guy. Loves everybody.” Indeed, I never heard him utter a bad word about anyone, never mind their race or ethnicity.

Bradley liked to call himself “a simple writer” and had even used the phrase as a working title for one of his autobiographical collections that we published on-line.1

“A simple writer” demonstrates his modesty. Bradley Smith was an excellent writer, perhaps plagued by the subject that he discovered one day in 1979 and then dedicated his life to. He was a man of courage, honesty, and honor. Most of all, I will remember him as a friend.

I am thankful to Ted O’Keefe for contributing his memories of our old friend and colleague, “A Revisionist Swashbuckler: My Memories of Bradley R. Smith” to this issue of Inconvenient History. Jett Rucker provides our feature article this quarter with a consideration of the impact of the Casablanca Conference of 1943 on the Holocaust. I am also very pleased to present Professor Faurisson’s New Year’s Eve thoughts on the state of revisionism, “The Revisionists’ Total Victory on the Historical and Scientific Level.” This issue also includes a Ralph Raico classic, “Arthur Ekrirch on American Militarism,” in which he casts a revisionist eye on American militarism from our country’s foundation down to the present day. K.R. Bolton returns this issue with an interesting look at World War II as a conflict largely fought between two systems of economy: globalization and autarchy in his “Origins of the Japanese-American War: A Conflict of Free Trade vs. Autarchy.” Our prolific reviewer of books and film Ezra MacVie provides an unusual look at the Oscar-winning film, Spotlight. I conclude this issue fittingly with a new installment in our “Profiles in History” series, outlining the career of Bradley Smith. This autobiographical sketch was written and revised and edited through the years — some of the edits provided by Bradley himself. While he was never directly involved with Inconvenient History, it is certain that, without his guidance and friendship through the years, our journal would never have been. And that, dear reader, is why this issue of Inconvenient History is dedicated to him. While it is not quite the Festschrift that he deserves, I suspect Bradley would be embarrassed by all the praise. He would likely suggest that we just get on with the work. And so we shall.

Notes:

| 1 | A Simple Writer was the working title of what would eventually be published in 2002 as Break His Bones: The Private Life of a Holocaust Revisionist. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 8(2) 2016

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a