Roots of Present World Conflict

Zionist Machinations and Western Duplicity during World War I

This paper contends that the present so-called “conflict of civilizations,” or “war on terrorism,” and the Arab-Israeli conflict have their origins in the covert machinations of the Great War that betrayed the Arabs, prolonged the war, and established a pestilential organism at the center of the Islamic world that will seemingly forever be a cause of conflict.

After the prior century of conflict between the European imperial powers and an agitated Arabia, World War I was an opportunity to forge a perhaps permanently cordial relationship between the West and the Arabs. Western imperial powers gave Arab leaders promises of independence for joining their war against the Ottomans.

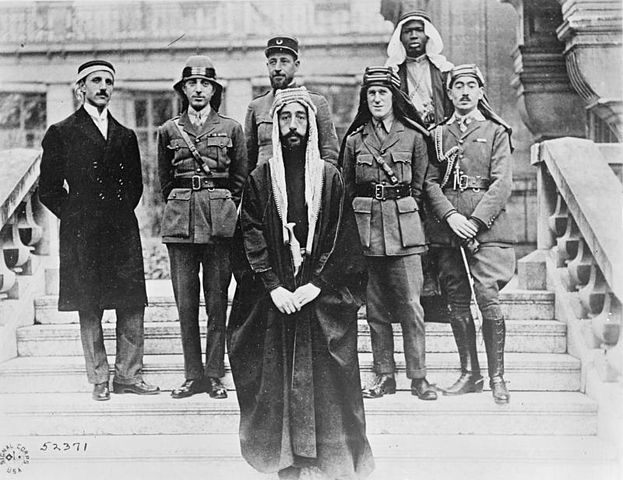

In October 1916, T. E. Lawrence, a British intelligence operative and one of the few who had a wide knowledge of the region, traveled with the British diplomat Sir Ronald Storrs on a mission to Arabia where in June 1916 Husayn ibn ‘Alī, amīr of Mecca had proclaimed a revolt against the Turks. Storrs and Lawrence talked with two of the amīr’s sons, Abdullah and Feisal, the latter then leading a revolt southwest of Medina. In Cairo, Lawrence urged the funding and equipping of those sheiks willing to revolt against the Turks, with the promise of independence. He was dispatched to Feisal’s army as adviser and liaison officer.

However, the Zionists and the British War Cabinet had reached a backroom deal. The war was going badly for the Allies, and the only hope was to persuade the USA to enter. On the other hand, the Zionists, who had placed their hopes in the Kaiser and the Ottoman Sultan for securing Palestine, had been rebuffed. Sultan Abdul Hamid had responded to Zionist leader Theodor Herzl that a Jewish state in Palestine was not agreeable, as his people had “fought for this land and fertilized it with their blood… let the Jews keep their millions.”[1] Zionist leaders approached the Kaiser, who was then trying to align with Turkey, the Zionists claiming that a Jewish state in Palestine would become an outpost of German culture.[2] The Kaiser did not acquiesce, and neither did the Czar.[3] The initial response from Britain to Herzl, by Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain, was to support a Jewish state in Kenya.[4]

By Lowell Thomas (http://www.cliohistory.org/thomas-lawrence/show/) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Lord Kitchener, British agent in Egypt and later secretary of state for war, realized the potential for Arab support against the Turks. On October 31, 1914, Kitchener sent a message to Hussein, sharif of Mecca and custodian of the Holy Places, pledging British support for Arab independence in return for support of the Allied war effort. The sharif was cautious, as he did not wish to replace Turkish rule, which allowed a measure of self-government, with that of Western colonialism. At this time the Ottoman sultan had declared a jihad against the Allies to mobilize Arab support for the war, and while the sharif feigned support, he sought out the views of Arab nationalist leaders. On 23 May 1915, Arab leaders formulated the Damascus Protocol, calling for independence for all Arab lands other than Aden, and the elimination of foreign privileges, but with a pro-British orientation in terms of trade and defense. Correspondence between Sharif Hussein and Sir Henry McMahon, British commissioner in Cairo, during 1915 and early 1916, culminated in McMahon’s guarantee of British support for independence within the requested boundaries, so long as French interests were not undermined.[7]

With both sides satisfied as to the guarantees, which included a sovereign Palestine, the Arab revolt broke out in the Hejaz on June 5, 1916. With Arab aid, the British were able to repulse the German attempt to take Aden and blockade the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. This was decisive.[8] The Arabs also diverted significant Turkish forces that had been intended for an attack on General Murray in his advance on Palestine. General Allenby referred to the Arab aid as “invaluable.” Arabs suffered much from Turkish vengeance. Tens of thousands of Arabs died of starvation in Palestine and Lebanon because the Turks withheld food. Jamal Pasha, leader of the Turkish forces, recorded that he had to use Turkish forces against Ibn Saud in the Arabian Peninsula when those troops should have been “defeating the British on the [Suez] Canal and capturing Cairo.”[9]

Lawrence in Seven Pillars of Wisdom related the importance of the Arab contribution to the Allied war effort, stating that “without Arab help England could not pay the price of winning its Turkish sector. When Damascus fell, the eastern war – probably the whole war – drew to an end.”[10] Lawrence stated of the Arab revolt that “it was an Arab war waged and led by Arabs for an Arab aim in Arabia.”[11] The Arab struggle owed little to British, or any other outside assistance. Lawrence relates in Seven Pillars with bitterness and shame the betrayal of the Arabs by his country’s leaders after the war:[12]

“For my work on the Arab front I had determined to accept nothing. The Cabinet raised the Arabs to fight for us by definite promises of self-government afterwards. Arabs believe in persons, not in institutions. They saw in me a free agent of the British Government, and demanded from me an endorsement of its written promises. So I had to join the conspiracy, and, for what my word was worth, assured the men of their reward. In our two years’ partnership under fire they grew accustomed to believing me and to think my Government, like myself, sincere. In this hope they performed some fine things, but, of course, instead of being proud of what we did together, I was bitterly ashamed.

It was evident from the beginning that if we won the war these promises would be dead paper, and had I been an honest adviser of the Arabs I would have advised them to go home and not risk their lives fighting for such stuff: but I salved myself with the hope that, by leading these Arabs madly in the final victory I would establish them, with arms in their hands, in a position so assured (if not dominant) that expediency would counsel to the Great Powers a fair settlement of their claims. In other words, I presumed (seeing no other leader with the will and power) that I would survive the campaigns, and be able to defeat not merely the Turks on the battlefield, but my own country and its allies in the council-chamber […].”

The dismissal of Sir Henry McMahon, British commissioner in Cairo, whose communications relaying British guarantees had set the stage for the Arab Revolt, confirmed Lawrence’s belief in Britain’s “essential insincerity” of their promises to the Arabs. This perfidy scarred Lawrence deeply for the rest of his life.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement & Betrayal of the Arabs

In the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 between Britain and France, “parts” of Palestine would be under international administration upon agreement among the Allies and with the Arabs represented by the sharif of Mecca.[13] This Anglo-French agreement already had the seeds of duplicity as it gave the two powers control over Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Transjordan, reneging on the commitment that had already been given by the British to Sharif Hussein, and without his knowledge. Lord Curzon remarked that the boundary lines drawn up by the Sykes-Picot agreement indicated “gross ignorance” and he assumed that it was never believed the agreement would be implemented. Prime Minister Lloyd George considered the Sykes-Picot Agreement foolish and dishonorable, but it was nonetheless implemented after the Allied victory.[14]

The Bolsheviks in the newly formed Soviet Union, eager to present themselves as the leaders of a world revolt against European colonialism, released the details of the Sykes-Picot Agreement, and the Turks took the matter to the Arabs in February 1918, stating that they were now willing to recognize Arab independence. Hussein sought clarification from Britain, and Lord Balfour replied that: “His Majesty’s Government confirms previous pledges respecting the recognition of the independence of the Arab countries.”[15] In 1918 Arab leaders in Cairo sought clarification from Britain and the British “Declaration to the Seven” on 16 June confirmed the previous pledge that had been made to Hussein.[16]

Author unknown [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The Balfour Declaration

Sir Mark Sykes, the individual responsible for the Sykes-Picot Agreement, approached the British War Cabinet with the suggestion that if Palestine was offered as a Jewish homeland, then Jewish sympathy could be mobilized for the Allied cause, and the USA might be induced to join the conflict. U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis used his influence to induce President Woodrow Wilson to adopt an interventionist policy.[17] In return for Zionist support the British reneged on their promises to the Arabs and secretly promised to support a Jewish homeland in Palestine; a guarantee that became known as the Balfour Declaration. This scheme prolonged the war, which might have been settled in a more equitable manner towards Germany and Austro-Hungary and hence would surely have changed the whole course of history.

Samuel Landman, a leading Zionist in Britain, related that several attempts had been made to bring the USA into the World War by appealing to “influential Jewish opinion,” but these had failed. James A. Malcolm, adviser to the British government on eastern affairs, who knew that President Wilson was under the influence of Chief Justice Brandeis, convinced Sykes, and then Picot and Goût of the French embassy in London, that the only way to get the USA into the war was to secure the support of American Jewry with the promise of Allied support for a Jewish state in Palestine.[18] Landman states that after reaching a “gentleman’s agreement” with the Zionist leaders, cable facilities were given to these Zionist leaders through the War Office, Foreign Office, and British embassies and legations, to communicate the agreement to Zionists throughout the world. Landman comments that “the change of official and public opinion as reflected in the American press in favor of joining the Allies in the War, was as gratifying as it was surprisingly rapid.”[19] Hence, the real power of the Zionists, even at that stage, over the press and politics was evident, as noted by Landman. Of the subsequent Balfour Declaration, Landman states:[20]

“The main consideration given by the Jewish people represented at the time by the leaders of the Zionist Organisation was their help in bringing President Wilson to the aid of the Allies […]. The prior Sykes-Picot Treaty of 1916, according to which Northern Palestine was to be politically detached and included in Syria (French sphere) so that the Jewish National Home should comprise the whole of Palestine in accordance with the promise previously made to them for their services by the British, Allied and American Governments and to give full effect to the Balfour Declaration, the terms of which had been settled and known to all Allied and associated belligerents, including the Arabs, before they were made public.”

The contention of Landman and other Zionists that these dealings between the Zionists and the Allies to hand Palestine over to the Zionists were known to the Arabs is nonsense, but has remained a basis of pro-Israeli propaganda. Even the Balfour Declaration refers only to British support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine, so long as it does not intrude upon the rights of the Palestinians. As shown above, the Arab leaders would not countenance a Jewish homeland in Palestine, even to the limited extent deceptively stated by Balfour. Landman refers to promises of “the whole of Palestine” being made to the Zionists. The Declaration unequivocally states no more and no less that:[21]

“His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a National Home for the Jewish People, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of that object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by the Jews in any other country.”

The British commander in Palestine, D. G. Hogarth, was instructed to assure Hussein that any settlement of Jews in Palestine would not be allowed to act in detriment to the Palestinians. Hussein for his part was willing to allow Jews to settle in Palestine and allow them ready access to the holy places, but would not accept a Jewish state. Hogarth was to relate that the promises being made to both Arabs and Jews simultaneously were not reconcilable.[22]

These machinations were confirmed by Lloyd George to the Palestine Royal Commission in 1937, the report of which states that George told the commission that if the Allies supported a Jewish homeland in Palestine the Zionist leaders had promised to “rally Jewish sentiment and support throughout the world to the allied cause. They kept their word.”[23]

Even after the Bolsheviks revealed these secret agreements, the Arabs continued to fight, due to Allied assurances that neither Sykes-Picot nor the Balfour Declaration “would undermine the promises that had been made to them.” Among the numerous reiterations of Allied support for the Arab cause, the Anglo-French Declaration of 9 November 1918 plainly stated that France and Britain would support setting up “indigenous governments and administrations in Syria (which included Palestine) and Mesopotamia (Iraq).”[24] With such assurances the Arab fight against the Turks was of crucial importance to the Allies.

James A. Malcolm

The memoir of James A. Malcolm, adviser to the British government on eastern affairs, on the Balfour Declaration, confirms all of Landman’s claims.[25] Malcolm states that his father was of Armenian stock, the family having settled centuries previously in Persia, where they were closely associated with the Sassoons, the opium-trading dynasty that became a power in British politics. The Malcolm family also served as liaison between the local Jewish community and another Jewish luminary, Sir Moses Montefiore in England. When Malcolm arrived in London in 1881 for his education he was placed under the guardianship of Sir Albert Sassoon, and came into contact with Zionists at an early stage. Malcolm acted officially for Armenian interests in the Holy Land in liaising with the British and French Governments, and was in ‘frequent’ contact with the British Cabinet Office, the Foreign Office and the War Office, the French and other Allied embassies in London, and met with French authorities in Paris.[26] These responsibilities brought Malcolm ‘into close relation with Sir Mark Sykes, under secretary of the War Cabinet for the Near East, and with M. Gout, his opposite number at the Quai d’Orsay, and M. Georges Picot, counsellor at the French embassy in London’.[27]

It is here that Malcolm introduces one of the early Zionist slurs against the Arabs in justifying his proposition to Sir Mark Sykes that the USA could be brought into the war if the British promised Palestine to the Jews as a national homeland. Efforts to secure Jewish support in the USA had so far failed because of the “very pro-German tendency among the wealthy American Jewish bankers and bond issuing houses, nearly all of German origin, and among Jewish journalists who took their cue from them.”[28] It was then that the whole Middle East imbroglio to the present was hatched by Malcolm with Sykes et al. Malcolm writes:[29]

“I informed him [Sykes] that there was a way to make American Jewry thoroughly pro-Ally, and make them conscious that only an Allied victory could be of permanent benefit to Jewry all over the world. I said to him, ‘You are going the wrong way about it. The well-to-do English Jews you meet and the Jewish clergy are not the real leaders of the Jewish people. You have overlooked what the call of nationality means. Do you know of the Zionist Movement?’ Sir Mark admitted ignorance of this movement, and I told him something about it and concluded by saying, ‘You can win the sympathy of the Jews everywhere, in one way only, and that way is by offering to try and secure Palestine for them.’”

In a lengthy note, Malcolm disparages the Arab Revolt and its contribution to the Allies, which contradicts the accounts by Lawrence in Seven Pillars, and the assessments of the British military leaders in that theater of war. Malcolm writes:[30]

“Early in the War the Arabs and their British friends represented that they were in a position to render very great assistance in the Middle East. It was on the strength of these representations and pretensions that the promise contained in the MacMahon letter to King Hussein was made. It was subsequently found that the Arabs were unable to ‘deliver the goods’ and the so-called ‘Revolt in the Desert’ was but a mirage. Their effort, at its maximum, never exceeded seven hundred tribesmen, but frequently less than 300, who careered about the desert some hundreds of miles behind the fighting line reporting for duty on ‘pay day.’ For this they received a remuneration of £200,000 per month in actual gold, which was delivered to them at Akabah. This sum represented a remuneration for every one of the tribesmen of more than the pay of a British Field Marshal. Lawrence himself made no secret of his profound disappointment with the Arab failure to carry out their engagements. That Hussein and Feyzal were not in a position to give any effective help was afterwards made abundantly clear by the fact that Ibn Saud was easily able to drive Hussein out of his kingdom.”

It should be noted that Malcolm claims that Lawrence was “profoundly disappointed” with the Arabs. As Seven Pillars, and Lawrence’s lifelong bitterness at the betrayal of the Arabs, shows, Malcolm is writing disinformation on the Arabs that has since become staple fare dished up by the Zionists and their Gentile apologists.

By American official photographer [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

“In the crucial weeks while Allenby’s stroke was being prepared and during its delivery, nearly half the Turkish forces south of Damascus were distracted by the Arab forces […]. What the absence of these forces meant to the success of Allenby’s stroke, it is easy to see. Nor did the Arab operation end when it had opened the way. For in the issue, it was the Arabs who almost entirely wiped out the Fourth Army, the still intact forces that might have barred the way to final victory. The wear and tear, the bodily and mental strain on men and material applied by the Arabs […] prepared the way that produced their (the Turks) defeat.”

Clubb and Evans in their paper on Lawrence at the Paris Peace Conference sum up the importance of the Arab Revolt:[33]

“Thanks to Lawrence and the Arabs, the British not only successfully invaded Palestine in the autumn of 1917 but continued north into Jerusalem, reaching the city on 11 December. From there they advanced into Damascus in September 1918, right into the very heart of Syria.”

Feisal’s small army adopted guerrilla methods that tied down the Turkish army, hitting bridges and trains. On July 6, 1917, after a two-month march, Arab forces captured Aqaba, on the northern tip of the Red Sea. Thereafter, Lawrence sought to coordinate the Arab actions with General Allenby’s advance towards Jerusalem. In November Lawrence was captured at Dar’ā by the Turks while reconnoitering the area dressed as a Bedouin. Recognized, he was brutalized by his captors before escaping. In August Lawrence participated in the victory parade through Jerusalem, then returned to Feisal’s forces who were pressing north. By now Lawrence had become lieutenant colonel and had been awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

The Arab army reached Damascus in October 1918. Lawrence had successfully established a government in Damascus, which was to serve as the center of a unified Arab state under King Feisal. Having established order in Syria he handed rulership to Feisal. However, the Sykes-Picot Agreement between France and Britain had mandated Syria as part of the French domain. French forces deposed the government that Lawrence had established for Feisal as the center of a unified Arab state with much bloodshed. They gave Feisal Iraq. A united Arab nation, thanks to Anglo-French perfidy and Zionist machinations, was not to be. History, as we know today, was shaped in the back rooms by lobbyists, politicians and diplomats in cynical disregard for the Arabs.

Lawrence returned to Britain shortly prior to the Armistice. At a royal audience on October 30, 1918, he politely declined the Order of the Bath and the Distinguished Service Order that was to be awarded to him by the King, leaving George V, as the King was to state, “holding the box in my hand.” Lawrence was demobilized as a lieutenant colonel in July 1919.

That year Lawrence, dressed in Bedouin garb, attended the Paris Peace Conference as a delegate in the entourage of Prince Feisal, with the approval of the British government. He vainly lobbied for Arab independence, and against the French mandate that was imposed over Syria and Lebanon. Clubb and Evans:[34]

“In the early days of the conference Lawrence and Feisal sought to present their case for Arab independence anywhere anytime, to anyone who would listen, delegates and pressmen alike, in private rooms and tea salons. They found willing audiences as people were curious about the mysterious yet regal Arab and his English paladin. When not courting their audiences, Feisal and Lawrence busied themselves preparing the statement that would be delivered at the conference.”

However, the French attempted to waylay and thwart Feisal at every turn, and the British insisted that Palestine was not part of any arrangement that had been made with the Arabs during the war.[35] While the French were insistent on the primacy of the Sykes-Picot Agreement in their dealings with the Arabs, the British had made conflicting promises to different interests, including conflicting statements on the status of Palestine. The Anglo-India Office (which had never been in favor of British support for an Arab Revolt) regarded the presence of Lawrence at Paris as “malign,” and that his views were not in accord with British policy. Lawrence was kept out of the British delegation that met again in Paris in 1919 to discuss the issue of Syria and France with Feisal. When Feisal returned to Damascus, he declared Syria to be independent on 7 March 1920 and he was declared King of Syria, which included Palestine and Lebanon. The French forces attacked, and Feisal was deposed on 24 July 1920, forced into exile in Italy,[36] but was installed as King of Mesopotamia in 1921 with the support of Britain.[37]

Arab support for the Allied cause during World War I, and the promises that the British made to the Arabs, have been all but forgotten, at least in the West. As recent history indicates, the Arabs have bargained in good faith with the West, and have been met with duplicity and betrayal. Now the West is reaping what its perfidious politicians had sown a century ago. There was nothing “inevitable” about this “clash of civilizations.” Good will existed during World War I and was trashed for the sake of Zionism. Sycophancy towards Israel has assured ever since that accord between the Arabs and the West remains forever unattainable.

Notes

| [1] | Alfred M. Lilienthal, The Zionist Connection What Price Peace? (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1978), p. 11. |

| [2] | One is reminded of the present Zionist claim that Israel is the outpost of “democracy” and of “Western values” in the region. |

| [3] | Lilienthal, op. cit., p. 11. |

| [4] | Ibid. |

| [5] | Ibid., p. 13. |

| [6] | Ibid. |

| [7] | Sami Hadawi, Bitter Harvest: Palestine 1914-79 (New York: Caravan Books, 1979), p. 11. |

| [8] | Lilienthal, op. cit., p. 17. |

| [9] | Quoted by Lilienthal, ibid., p. 17. |

| [10] | T. E. Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom (London: Black House Publishing, 2013), p. 666. |

| [11] | Ibid., p. 29. |

| [12] | Ibid., pp. 31-32. |

| [13] | Hadawi, op. cit., p. 12. |

| [14] | Ibid., pp. 12-13. |

| [15] | Lilienthal, op. cit., p. 18. |

| [16] | Ibid. |

| [17] | Hadawi, op. cit., p. 13. |

| [18] | Samuel Landman, Great Britain, the Jews and Palestine (London: New Zionist Press, 1936), pp. 2-3. Landman was honorary secretary of the Joint Zionist Council of the United Kingdom, 1912; joint editor of The Zionist 1913-1914; solicitor and secretary for the Zionist Organisation 1917-1922; and adviser to the New Zionist Organisation, ca. 1930s. |

| [19] | Landman, ibid., pp. 3-4. |

| [20] | Ibid., p. 4. |

| [21] | Lord Balfour to Lord Rothschild, 2 November 1917. |

| [22] | Lilienthal, op. cit., pp. 18-19. |

| [23] | Palestine Royal Commission Report cited by Hadawi, op. cit., p. 14. |

| [24] | Hadawi, ibid., p. 15. |

| [25] | James A. Malcolm, “Origins of the Balfour Declaration: Dr. Weizmann’s Contribution” (London, 1944). The entire document can be read online at: http://www.mailstar.net/malcolm.html |

| [26] | Ibid., p. 2. |

| [27] | Ibid. |

| [28] | Ibid. |

| [29] | Ibid. |

| [30] | Ibid., note on p. 2. |

| [31] | Liddell Hart, Lawrence of Arabia (New York: Da Capo Press, 1989 [1935]). |

| [32] | Quoted by Hadawi, op. cit., p. 16. |

| [33] | Andrew Clubb and C. T. Evans, “T. E. Lawrence and the Arab Cause at the Paris Peace Conference.” Online: http://www.ctevans.net/Versailles/Diplomats/Lawrence/Background.html |

| [34] | Ibid. |

| [35] | Ibid., “Politics gets in the way of a Settlement’.” |

| [36] | Ibid., “A Death in the Family and a Parting of Ways,” Online: http://www.ctevans.net/Versailles/Diplomats/Lawrence/Paper.html |

| [37] | Ibid., “Postscript,” Online: http://www.ctevans.net/Versailles/Diplomats/Lawrence/Postscript.html |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 6(3) 2014

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a