The Chief Culprit

A Review

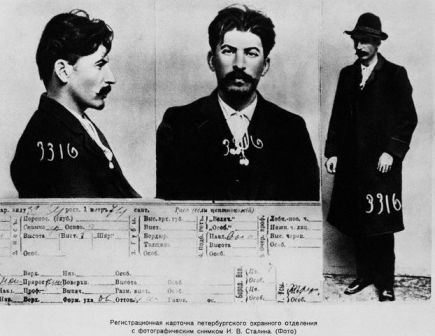

The Chief Culprit: Stalin’s Grand Design to Start World War II, by Viktor Suvorov Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 2008, 328pp., illustrated, with notes, bibliography, indexed.

The post-1945 war crimes trials in Nuremberg are underway and the international press excitedly covers the proceedings. The tribunal itself consists of justices not from victor powers but from wartime neutrals – Switzerland, Thailand… in order to ensure fairness and justice.

The accused are called forth—

The Soviet Union is first. Their political and military leaders face serious prosecutions for plotting and waging aggressive war against Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Rumania, and Poland. They face accusations of enslaving and working to death many hundreds of thousands, even millions, of captured German and Japanese prisoners of war. The new postwar word ‘genocide’ is used, coupled with more and greater accusations of having worked to death scores of millions of their own citizens in their GULAG system of labor camps, a veritable holocaust within their own borders. They are additionally charged with responsibility for the genocide in which somewhere between 6 and 12 million German civilians perish from forced population transfers from their own ancestral homelands into a now truncated postwar Germany – transfers in which rape, torture, murder, and complete dispossession are more the rule rather than the exception.

The British come next, facing a well-prepared case of the mass murder of German civilians through a vengeful bombing campaign. Their defense case of ‘…to break German morale’ quickly collapses as the prosecution demonstrates that it was sheer mass murder motivated by hatred, and not a ‘morale’ campaign that in fact merely strengthened German willpower and morale. The British also face charges of plotting and waging aggressive war against Norway in 1940, thus extending the war into neutral Scandinavia. They next face angry denunciation for having attacked the neutral Vichy French fleet in 1940 in which hundreds of French sailors died – this being another crime of plotting and waging aggressive war. Finally the charge of deliberately starving the entire civilian population of their zone of occupation is levied against them, in which many thousands perish and others suffer permanent ill health effects.

The French are trotted in after the British. They face charges of the mass murder of German prisoners of war following war’s end, by enslaving and working them to death, through casual executions, and deliberately depriving their prisoners of food, shelter, and medical care. They also face the accusation of deliberately bringing African colonial troops into occupied Germany and giving them a free hand to rape, loot, and murder the helpless civilian population.

Finally the Americans enter the dock. They are charged with much the same genocidal bombing campaign as the British waged, along with a far greater case regarding the mass murder of German POWs through the same means as waged by the French against their own prisoners: starvation, exposure, denial of medical care, murder, etc., and here the number of victims jump to well over a million and closer to two million. And that is not all. The Americans are also accused of mass rape, large scale looting, the enslavement or semi-enslavement of POWs…

There is also the formulation of ‘crimes against peace’ charges brought against Britain, France, and especially the United States, in their pre-war behind the scenes political campaigns of pressuring the Poles towards intransigence in their negotiations with the Germans over Danzig and a corridor to East Prussia – which intransigence leading directly to the 1939 war.

The scores of millions of those murdered by the eastern and western Allies reach into the scores of millions and ludicrously dwarf the alleged ‘six million’ figure laid on the Germans…

Of course such trials did not happen. Yet this is the justice that should have prevailed after the war if war trials and prosecutions were conducted fairly. The point is that the very nations who stood as the victor powers and whose representatives prosecuted and judged the defeated nation Germany for crimes against peace and plotting aggressive war, were themselves at least as guilty and very likely far more so.

And none so guilty as Joseph Stalin.

Viktor Suvorov in his latest book The Chief Culprit especially brings forth the question of why Joseph Stalin and his political and military underlings were not prosecuted for plotting aggressive war against all of Europe.

This book represents a synthesis of the author’s published works following his landmark Icebreaker, works which have not seen English editions but have appeared in French and Russian. The focus of Icebreaker was mainly that of the military preparations which Stalin had undertaken prior to his invasion of Europe planned for July 1942. Suvorov there had shown that weapons, training, and positioning of the Red Army were entirely predicated upon aggressive war.

Culprit has more of a political and strategic focus. Suvorov demonstrates the fundamental Leninist-Stalinist long-term strategy of bringing the entire world into the Soviet Union, one ‘republic’ at a time; some peacefully perhaps, but most others through war. In Marxist jargon, ‘just wars’ are wars in which the goal is to bring a nation into the ‘Socialist’ camp, while ‘unjust wars’ are wars of any other type.

The Soviet economy was already a shambles by the late 1930s, its resources having been consumed in massive military spending and buildup. Suvorov points out that the only way in which the USSR and its Marxist-Leninist system could survive would be through the conquest and absorption of successful capitalist nations. The proposed construction of the magnificent ‘Palace of Soviets’ in Moscow was meant to be a sort of reception structure for each new ‘Soviet republic’ – i.e. Germany, France, Spain, Sweden, England, and all the rest – are admitted one by one after their conquest. However, following the German invasion of June 1941 and the rapid advance of Hitler’s armies, the construction was abandoned.

Suvorov takes us into the mind of Stalin and presents a very intelligent, cunning, but also eminently criminal master of grand strategy. A hero to the faithful in that he made a relatively backward country into a semi-modern industrial and military giant, he would have been an even greater hero to them if he’d succeeded in incorporating all of Europe into the Soviet colossus. But it was not to be, as Hitler’s invasion pre-empted that of Stalin’s.

The German defendants at Nuremberg presented the invasion of the USSR as a pre-emptive war. They were aware of the Soviet buildup on their borders and their intelligence services knew perfectly well of the pending invasion by the Red Army. In 1945 no one believed them. Even today Suvorov’s thesis is generally rejected as absurd, even strange and the received mythology of an innocent Soviet Union being taken unawares by the Nazi aggressor persists.

Suvorov shows how Soviet propaganda rapidly shifted into this mythology soon after the German invasion. The Red Army’s defeats in the initial period of conflict were highlighted and condemned, the leadership being frankly presented as asleep at the wheel, irresponsible, and having failed. The later defeats and huge encirclements were, however, not mentioned, as their relationship to a surprise invasion could not be sustained.

Stalin himself, in Suvorov’s view, simply could not believe that the Germans would invade at all. Of course he knew of the German buildup, but he must have seen this as defensive. The Soviets were so superior in masses of weapons and vehicles and aircraft and troops – all offensively trained and deployed of course – simply made a German invasion impossible, insane, even suicidal.

Suvorov firmly believes Hitler to be a creation or creature of Stalin. That Hitler could only have taken power in 1933 thanks to the powerful communist party there having failed to prevent it – and that failure he sees as something designed or ordered by Stalin. Why? Because Stalin planned to use Hitler as the man who would remake Germany’s military and ultimately use it to rework Europe’s frontiers and plunge the continent into war again – a war in which the capitalist powers would fight it out and exhaust themselves, and in their final state of exhaustion be overwhelmed by the massive Red Army. He convincingly demonstrates the heavy German reliance on Rumanian oil, and how easily Stalin could have seized the oilfields just beyond their border and effectively strangled the German war machine ending the war at virtually any time he chose. But he did nothing in accordance with the aforementioned strategy of exhausting the capitalist West through prolonged conflict. This plan also went awry of course, as Germany’s enemies were snuffed out in one lightning campaign after another. The oilfields themselves would be captured and protected by German troops.

Suvorov credits Stalin with these masterful long-range strategic plans, all in accordance with the Leninist plan to absorb the world into Socialism, but does not adequately explain how the Germans foiled them through rapid advances and superior tactical leadership. He does hint, however, at Stalin being out-maneuvered by Hitler, in that as the Nazi victories in Russia piled up through the summer and fall of 1941, Stalin himself went into a deep depression and virtually disappeared into the Kremlin, alone, and fearing imminent arrest by his colleagues. But thanks to the ‘cult of personality’ into which Stalin had built himself in the mind of the citizenry, he was needed as a symbol of leadership, hope, and resistance. He thus escaped arrest and eventually returned to his role as generalissimo, hero, and savior of the motherland.

An interesting analysis made by the author is that of the Tukachevsky affair. A popular interpretation is that the German SS intelligence service had planted documents with the Soviets suggesting that this Soviet Marshal and many others in senior military positions were plotting against Stalin, this then leading Stalin’s natural paranoia into a huge purge of the Soviet military leadership, effectively eliminating most of the leading professionals and greatly weakening the USSR’s ability to wage war. The author presents a strong case that Marshal Tukachevsky was nowhere near the effective leader most historians make him out to be, and that the Red Army was far from lacking in senior, experienced officers in mid-1941.

The purges themselves, the author asserts, were rational, albeit ruthless, measures taken by Stalin to ‘tame’ the Red Army into a force absolutely obedient to Stalin’s will for the upcoming great war against Europe.

Chief Culprit shows a Soviet Union far better prepared for major conflict than Nazi Germany. Suvorov points out that the German forces were not really prepared for a war such as that against the USSR. They did not have enough tanks, most of their transport was that of antiquated horse-drawn wagons, the troops and vehicles were exhausted and worn down from earlier campaigns. And yet these forces destroyed one Soviet army after another until almost nothing was left and they were at the gates of Moscow and victory was almost within their grasp.

The standard German explanation for failure in 1941 talks of the severest Russian winter in decades, of oceans of mud, of vast spaces and lack of roads to cross them. There is also the issue of the six-week German delay of Operation Barbarossa due to the unanticipated campaigns in Yugoslavia and Greece thanks to Italian military issues in those countries.

Suvorov rejects these explanations as useful to German propaganda at the time but ultimately without merit as explanations; he shows the German forces as simply not sufficient to defeat the Soviet Union. And yet Germany had no choice but to invade, not only to pre-empt Stalin’s own invasion plans and thus to prevent Germany and Europe from falling into his hands, but also that conflict was unavoidable given the increasing aggressiveness and escalating demands of the USSR. It ultimately came down to a question of who would strike first. While Stalin had a choice, Hitler did not. Thus while Suvorov convincingly presents both Hitler and Stalin as aggressors, Stalin clearly emerges as the ‘chief culprit’.

Will historians come to accept this thesis, or will they continue to hide behind the myth that Adolf Hitler was the only aggressor of World War Two in Europe? There does not seem to be much value placed upon historical truth these days. Nonetheless, Suvorov’s work shines a ray of light into this otherwise politicized field.

Copyrighted 2008 by Joseph Bishop. All rights reserved.

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, vol. 1, no. 2 (fall 2009)

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a