The Laconia Incident

While you’re celebrating the 80th anniversary of D-Day, allow me to tell you another war story you’ve probably never heard (I graduated Phi Beta Kappa with a major in American History from an Ivy League school and I never had!). You may find it doesn’t fill you with the same patriotic pride as the Allied landing, but it will provide a fuller understanding of how unheroic war can be, and that’s something we all should face.

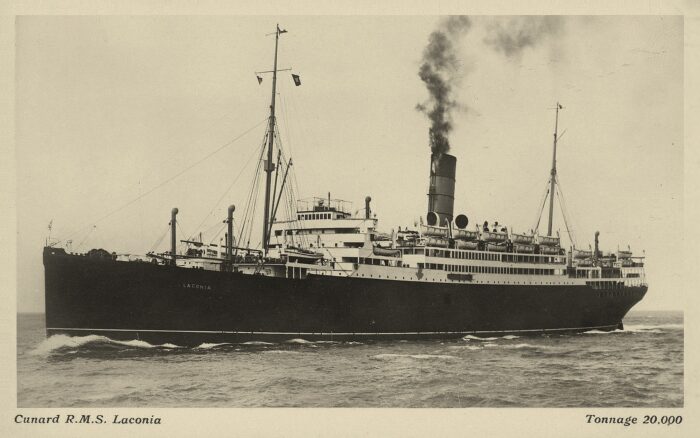

“The Laconia Incident,” as the story is known,[1] begins with a German submarine, U-156, sinking the British passenger ship RMS Laconia, off the coast of Africa in September 1942. Though a passenger ship, the Laconia was a legitimate target according to the rules of war as it was armed and carrying troops. On board were 463 officers and crew, 87 civilians, 286 British soldiers, 1,793 Italian prisoners, and 103 Polish soldiers.

As the ship was sinking, most of the passengers made it into lifeboats, except the Italians, who were trapped in locked cargo holds. Still, most of them made it out as well through smashed hatches or ventilation shafts, only to be shot, bayoneted, or have their hands hacked off when they tried to climb into the lifeboats. The blood attracted sharks who feasted on the living and the dead.

When the submarine surfaced, expecting to find just a few dozen of the ship’s officers alive, they were shocked to see 2000 survivors floundering in the lifeboats or in the water. The Germans immediately commenced a rescue operation, securing four of the lifeboats to the sub and loading her deck with those plucked from the waves. The captain of the sub broadcast an uncoded message in English calling for any ships in the area to come to the rescue, promising not to attack them so long as they were not themselves attacked. He also had a large Red Cross flag draped over the deck, an internationally recognized sign that the sub was engaged in a rescue operation. Informed of the situation, Admiral Dönitz, head of German submarine operations, ordered seven U-boats to proceed to the site of the sinking to assist U-156.

The British thought the captain’s message was a ruse meant to attract Allied ships into range, and they passed their suspicion on to the American military, who dispatched a bomber from their base on Ascension Island to check out the situation. Despite a captured British officer radioing a message to the pilot of the plane that Allied personnel and civilians, including women and children, were onboard the sub, the bomber made four bomb runs. The bombs failed to release on the first three runs, but two bombs were successfully dropped on the fourth. The crew of the bomber reported they had sunk the German sub (and were awarded medals on that basis), when in fact they had missed the sub but sunk two of the survivor-packed lifeboats. (No doubt the medals are proudly displayed each Memorial Day by the crew’s descendants, unaware of the less-than-heroic full story,). The sub immediately submerged but did so slowly so as to give the prisoners on deck a chance as they were forced back into the water.

Most of the survivors were soon picked up by Vichy French ships (France then having a government which adopted a neutral position on the war), but two lifeboats had separated from the others and made for the coast of Africa. They were not picked up till a month later, only 20 of the 120 in the boats being still alive. All in all, of the Laconia’s original complement of 2,741, 1,083 survived (most of the dead were Italian POWs).[2]

But the story of the Laconia does not end there. Up until that point, it was common for U-boats to assist torpedoed survivors with food, water, and medical care, but in response to U-156 being fired upon while engaged in a rescue operation, Admiral Dönitz, head of German submarine operations, issued an order, the Laconia Order, which prohibited U-boats from attempting to rescue survivors. To appease the consciences of his sailors, Dönitz appended this reminder to the order: “Be harsh. Remember that the enemy has no regard for women and children when bombing German cities!.” Nonetheless, even after the order was given, U-boats still occasionally provided aid to survivors.

For issuing the Laconia Order, Dönitz was prosecuted at Nuremberg, but the prosecution’s case fell apart when the full story of the Laconia came out, especially after Admiral Nimitz, commander of the US Pacific Fleet, testified – to his credit – that the United States had practiced “unrestricted submarine warfare” (a policy allowing submarines to sink merchant ships without warning) from the first day the United States entered the war. No wonder Supreme Court Chief Justice Harlan Stone disparaged the Nuremberg Tribunal as a “high-grade lynching party.”[3] Makes you wonder what other war crimes the Nazi’s may have been unjustly accused of (e.g., gas chambers?).[4]

Maybe if we memorialized the Laconia Incident the way we do D-Day, it would help lift the blood-red fog draped – intentionally and unintentionally – over war’s realities – so the heavenly blue sky of peace can shine through.

Endnotes

| [1] | See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laconia_incident, which is also the source of the illustrations shown in this article. |

| [2] | If you are gloating over the Germans sinking a ship carrying their own allies, remember the case of the Shinyō Maru (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shin’yō_Maru_incident), a Japanese ship carrying 750 Allied prisoners which was sunk in 1944 by an American submarine, only 82 POWs surviving. Symbolic of the fog thrown over unfortunate events like this by those promoting warrior zealotry, the crew of the submarine was not informed the ship they sank was carrying Allied prisoners until after the war was over. |

| [3] | “Remarks of the Chief Justice,” American Law Institute Annual Meeting, May 17, 2004,” https://www.supremecourt.gov/publicinfo/speeches/sp_05-17-04a.html. |

| [4] | I met a Czech woman recently to whom I expressed my admiration for the beauty of Prague, “The City of 100 Spires”, and remarked how lucky it was that it wasn’t bombed during the Second World War. She explained that Hitler spared the city to show that the Nazis were not heartless barbarians. Not so with the allies, who firebombed another of Europe’s most beautiful cities, Dresden – killing 100,000 – though the attack served no military purpose other than to slow the Soviet advance on Berlin (They got there first anyway). Churchill confided in his diary that, had Britain lost the war, he would have been hung as a war criminal for Dresden alone (No idea whether Eisenhower was equally honest with himself). Makes me wonder whether it was the good guys who won the war. (Frankly, I don’t think there were any good guys… or bad guys, just people like you and me caught up, by circumstance or choice, in a horrible, perplexing situation where they strove to do what was required of them and morality was obscured by the necessities of the moment). |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, Vol. 16, No. 2, 2024

Other contributors to this document:

Editor’s comments: