Uncle Sam, May I?

Editorial

The US elections this past November 6 were dominated by a close presidential race whose partisans, if not the candidates themselves, seemed to entertain mutually hostile visions of how government should proceed into the future. As is the American custom, however, myriad issues and candidates went before the electorate under the guise of “local” issues on the same occasion and, in fact, on the same ballots. And inevitably, a few of these contests were actually bellwethers of issues of not just national, but in fact global import.

Of these, the initiatives to legalize the possession and production of marijuana stands out, not just in terms of its social/political/economic importance, but in the fact that in two states—Colorado and Washington—the private growing and use of marijuana has been decriminalized, at least so far as those two states’ law-enforcement apparatuses are concerned.

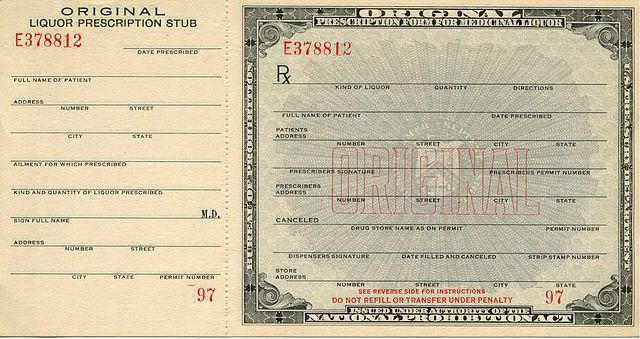

The movement to legalize marijuana invites comparison with an American project of almost a hundred years ago to prohibit the sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages, while at the same time it illuminates a panoply of profound human-rights issues as well the political maelstroms that occasionally arise in the ambit of the United States’ distinctive “federal” system of quaintly mischaracterized “sovereign states.”

It has been little noted that the impetus for Franklin D. Roosevelt’s famous emancipation of America’s tipplers was driven by his government’s desperate need for revenues, these having been deeply reduced by the ravages of the Depression that entered its third year in FDR’s first year (1933) in office. Repeal (of Prohibition) had been pushed since Prohibition’s first day by two groups, membership in both of which was claimed by many of the so-called “Wets.” The first group, the smaller, held that regulation of what people could ingest—or of alcohol, at any rate—was not a fit office of government; that people should be free in this as well as all other respects in which their actions did not hurt others. The numbers of this group became vastly greater as experience developed with the extensive evils and destruction that attended the enforcement of Prohibition.

The second group, far larger, even, than its considerable confessing membership, simply wanted to be able to drink, and/or or to purvey drinks, without breaking the law. Those advocating Prohibition, of course, likewise fell into disparate categories celebrated even to the present day by contemporary analogies with the “Baptists and bootleggers” whose incongruous alliance sustained Prohibition long after its insufferable costs became apparent even to those who were happy if no drop of alcohol ever passed their lips.

But this battle, not unlike today’s prohibition of marijuana and other recreational drugs, raged on endlessly until the federal government’s revenues were ravaged by the Depression, and Prohibition tumbled as wheat before the scythe of the government’s ravenous appetite for the people’s pelf. America’s federal system at that time displayed a spectacle that it has manifested on a number of occasions: various states anticipated the federal government’s Prohibition by voting themselves “dry” in considerable numbers before the national drought struck in 1933. This pattern also appeared, among other times, in states including women in their electorates before the 1920 Constitutional amendment requiring all states to do so, and in states liberalizing permission for women to have abortions prior to the 1973 Supreme Court decision striking down the laws in the laggard states that still restricted abortion in ways the Court deemed contrary to the dictates of the Constitution.

Today, in a tax-revenue context not unlike that of the early Thirties, it appears that America’s rambunctious states are leading the charge for repeal, a rolling-back of America’s long-standing War on Drugs that, compared with movement toward prohibition, is like driving a vehicle in reverse compared with driving it forward. Or perhaps even a tractor-trailer (truck). Or a ship—it’s awkward, hazardous, and the driver’s ability to go exactly where he would like to is greatly impaired.

This labored analogy arises from the fact that federal law applies throughout every state, including states that have vacated penalties on possession and use of marijuana from their statute books. And the War on Drugs has been a federal (as well as state) war at least since the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914. This means that possession and use of marijuana continues to be (only) a federal crime in Colorado and Washington.

And this, in turn, augurs for stand-offs such as did not attend the repeal of Prohibition, where sentiment for repeal seems to have been concentrated in cities, rather than having the statewide appeal demonstrated in the two “free” states mentioned, as well as a number of other states, notably California, in which production and use of marijuana is licensed for certain “medical” purposes and remains under the control of the practitioners (chiefly doctors) who currently are licensed to authorize the purchase of prescription drugs. Although many states had their own Prohibitions, most predating the federal one, none of these repealed its Prohibition prior to the federal repeal, and Prohibition remained the de jure situation throughout all states, including those that had never prohibited alcohol in the first place.

Today’s developments would not seem to presage an actual civil war between the federal government and those who wish to banish the federal War on Drugs from their territories. Armed confrontations between state and federal law-enforcement officers in the “free” states have been mooted, though, as the analogy of backing up a tractor-trailer rig was meant to illuminate, the specific directions this conflict may take seem very hard to predict. Federal invasions of “free” states would seem hard to imagine, but the analogy holds.

Federal Prohibition of alcohol was but 14 years old at its death, while the federal War on Drugs is almost 100 years old at this point. The alcohol, pharmaceuticals, and incarceration industries are fighting repeal tooth and nail, along with the “Baptists,” who continue to feel that the tragic destruction and injustice of the War on Drugs is still justified to forfend the chaos that must arise if it is not waged with ever-mounting ferocity.

And that’s the interesting thing about history: it keeps happening.

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 4(4) (2012)

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a