War Criminals in Israel

Israel collects war criminals. Of course, in the course of its never-ending conflicts with its neighbors, it has produced its own abundant crops of home-grown, even native, war criminals, but here, I wish to concentrate on war criminals, real and supposed, imported from other lands whose crimes even antedate Israel itself—I am interested, in fact, in war criminals whose crimes were committed, if crimes they were, in Europe during and immediately after World War II, either upon Jews or by Jews. In fact, four famous and not-so-famous cases themselves embody such a wide variety of charges, apprehensions, verdicts, trials and sentences that they will suffice for the exploration of the subject that I contemplate.

The most-famous of these accused war criminals is Adolf Eichmann, who needs no more introduction than his name. Next most-famous, perhaps, is Yitzhak Arad, a Jew from Lithuania who has lived most of his life in Israel and gained a name in certain circles of scholarly advocacy as the author of several books purporting to describe, in great detail, various phases of the historical subject embraced by the term “the Holocaust.” Next would come the late John Demjanjuk, a Gentile from Ukraine who lived most of his life in America whose citizenship in that country was twice granted, and twice revoked during the travails he experienced in the last three decades of his life while persecuted by a succession of international Holocaust avengers. The one most spared the revealing light of international notoriety, and even a trial, is one Salomon Morel, a Jew from Poland who was commandant of the post-war Zgoda/Świętochłowice concentration camp for Prussian German expellees in Poland, and also spent the latter part of his life in Israel without calling any further attention to himself, nor having it come to him in the manner experienced by the Gentiles in this list. The cases will be reviewed in the order in which they became public.

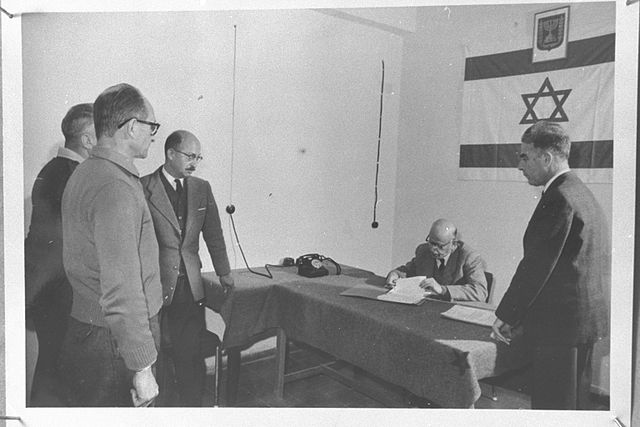

Photo: 1961.

By Israel Government Press Office (Israel National Photo Collection D412-001) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Israel abducted Eichmann in Argentina in 1960, after Eichmann had been living there since the war, and secretly spirited him to Israel, where Israel proudly proclaimed its violation of Argentina’s sovereignty, and proceeded to put on a show “trial” of this early Holocaust defendant, which concluded with his being sentenced to death, and duly hanged in 1961. While Israel’s Gestapo, the Mossad, is known to have murdered a good number of people outside Israel, and Israel is known to have extradited a comparable number of unfortunates for crimes such as those of which Eichmann was accused, Eichmann’s would appear to be the only case of covert “extradition” performed by the Mossad without the host country’s knowledge or permission.

Eichmann doggedly testified at his “trial,” confirming in the minds of his captors and their sympathizers his guilt for all time. The same testimony, in the minds of otherwise-motivated auditors, largely exonerated Eichmann of anything worse than carrying out his orders, and even indicted some leaders of Jewish communities for at least as much guilt in carrying out the Holocaust as Eichmann himself could be seen to bear. While the entire process was literally terminal for Eichmann, it provided an auspicious launch not only for the Holocaust culture we observe everywhere today, but for its unlovely offspring, the aggressive young Israel. Eichmann “gave” his life for Israel, and for generations of Holocaust victims as yet unborn.

Salomon Morel’s story is much befogged by blood and smoke, arising as it does during the early 1940s when invasions, conquests and occupations from both east and west washed over his birthplace in Poland. His own area did not become subject to German occupation until after Operation Barbarossa was launched from the German side on June 22, 1941, after which he went underground in a manner that the Polish Institute of National Remembrance describes as rankly opportunist, if not outright predatory. When the gang of robbers of which he was a member was captured by the Polish People’s Army, he skedaddled over to the communist side of the resistance, leaving his brothers and fellow gang members to face the consequences. Morel found success as a communist and, when Soviet communists became the masters of Poland, Salomon Morel found his calling—and an opportunity for revenge—as a jailer.

Specifically, newly minted Colonel Morel became commandant of the Zgoda/Świętochłowice concentration camp for Prussian German expellees in Poland, a camp full, as he likely saw it, of people related to those who identified his fellow Jews as enemies and subsequently enslaved them in great numbers in the course of fighting a war that ultimately took on existential consequences for the Germans. He may also have believed the tales of mass torture or even genocide the Germans are supposed to have committed against his people.

Whatever Morel’s beliefs, the Zgoda camp became legendary as one of many counter-concentration camps for Germans in which, even if there were no gas chambers, Polish-German men, women and children died in great numbers in the most horrendous conditions imaginable, even to those who imagined horrendous conditions in the camps established by the German government. Morel and his murderous Jewish cadre of camp operatives were immortally documented in John Sack’s An Eye for an Eye[2], an account of revenge taken by Jews in Europe after World War II against people they felt were “German enough” to merit retribution for the atrocities they felt had been committed against Jews under the National Socialist policies that ruled Germany from 1933 to 1945.

In 1990, however, Morel’s red star began to set with the fall of the Soviet Union. By 1992, Colonel Morel could read the writing on the wall, and he lit out, as fellow Communist Yitzhak Arad had long since done (see below) for Israel, to make Aliyah. Israel met Poland’s 1998 request for Morel’s extradition for crimes against humanity with the response that the statute of limitations had run out.

Statutes of limitation don’t apply to such as Oskar Groening or John Demjanjuk (see below), but they certainly do to Salomon Morel, especially when he is safely ensconced in the national home of the Jews, where he died a peaceful death in 2007.

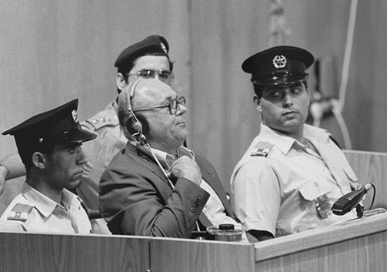

USHMM Photograph #65266, courtesy of Israel Government Press Office, [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Demjanjuk, however, got away from all this quite handily when, in 1952, he managed to emigrate to the United States, where he became an auto worker. There he lived, worked, and raised a family in much the same manner as other Americans, native-born or immigrant alike, until Demjanjuk rashly allowed his wife Vera to return to their native Ukraine. There, Vera let it out that John, for whom his mother had been receiving survivor’s benefits from the government, was still very much alive. She didn’t realize that this revelation put her husband under suspicion of having been a turncoat.

Demjanjuk’s mother’s benefactors were not long in exacting revenge for this assault on the national treasury of the Ukrainian people committed unwittingly by the bereft mother. The authorities, in possession of Demjanjuk’s postwar applications for a driver’s license in East Germany, cobbled up a much-discredited “identification card” for Demjanjuk as a guard at the notorious Trawniki concentration camp, and we were off to the races. Demjanjuk’s troubles with the laws of Israel, Germany and the US never ended after that.

He was extradited to Israel (the place whose statutes of limitation barred the extradition of Salomon Morel), tried there, sentenced to death, and subsequently freed by the Israeli Supreme Court’s ruling that there was insufficient evidence to convict him, and a subsequent case, brought after restoration of his US citizenship from Germany, where he was again being tried in the light of “new evidence.”

He died during that trial, a casualty of … something. Of World War II? Of Nazism? Of Communism? Of Zionism? Of American immigration law? It might seem, at least in John Demjanjuk’s case, that the vises of history close from every direction imaginable. Who won the war? Who controls the apparatus of the state after the war? Who controls the media after the war? Who has the most money after the war?

Yitzhak Arad grew up Jewish in a place that was part of Poland until he was 19, after which it was part of Lithuania. Alone among our war criminals, Arad enjoys a reputation, at least in certain partisan quarters, as a “historian,” or at least, narrator-from-the-scene, of innumerable atrocities, or resistance measures depending on your perspective, not only in the area in which he was born, but as well in Israel, in the violent gestation of which he participated quite as much, and quite as particularly, as he participated in the removal of German occupiers of his native lands, along with other persons whose ethnic, religious or political affiliations differed from his own.

Specifically, Arad participated (in Europe, at least) in intra-resistance conflicts in which he is recorded as having killed other resistance fighters whose affiliations lacked the Soviet/communist/Jewish ones enjoyed by the partisans among whom he fought. Whether Arad committed his atrocities in the name of Jewish domination or communist domination remains ambiguous to this very day; it certainly would have been ambiguous to Arad at the time, though it is likewise unclear to what extent the distinction mattered to him.

As it turned out, Arad’s communists won, but Arad took off for the Promised Land in 1945, where there was plenty of activity of the sort in which he had been successful already. Arad’s side won again in 1948, when the state of Israel was born amid the ashes of Palestine, and Arad became a brigadier general in Israel’s Defense Force before segueing to his career as an academic historian. Bloody times, it might be reasoned, are the better recalled and recounted when your own hands are covered with the stuff. Arad has commanded not only such credibility, but credence as well on the part of people eager to support his particular view of the events.

But back home in Lithuania, Arad’s old friends the communists were ousted in 1990. But it wasn’t until 2007 that historical investigators of the new regime got around to Arad’s actions during World War II against their side of the resistance to Lithuania’s many occupations. But, fortunately for Arad, his adopted country just said the claim was an anti-Semitic plot, and refused to cooperate with it.

Countries involved in the foregoing list include Argentina, Germany, Israel, Lithuania, Poland and the United States. Israel, of course, is the one common to all the cases. Israel extradites people accused of harming Jews, however peripherally and long ago that may be, or it just abducts them outright, and it sentences them to death. Those (Jews) accused of harming non-Jews, it welcomes in, and once they are safely ensconced within the walls rising even now around Eretz Israel, it rebuffs efforts to bring them to justice with impunity.

Israel’s wards may plainly be seen to be, or have been, partisans. Of Israel itself, it may also be said that it is partisan—in every pejorative sense of the word.

Notes

| [1] | The most famous of these works is Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem (New York: Viking Press, 1963), but an even better account of the trial is The Real Eichmann Trial by Paul Rassinier (English translation Steppingstones Publications, Silver Spring, Md., 1979). |

| [2] | John Sack, An Eye for an Eye: The Untold Story of Jewish Revenge against Germans in 1945 (New York: Basic Books, 1993). |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 2015, vol. 7, no. 3

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a