What the Germans Knew

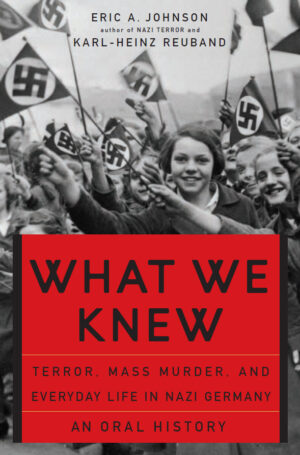

Another important issue regarding the Holocaust is the awareness of the German public about it, either civilians or soldiers. What did the Germans know? Two researchers, historian Eric A. Johnson and sociologist Karl-Heinz Reuband, started searching for answers in 1993. After nearly 3,000 written surveys and 200 interviews the result was the book What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder, and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany (Basic Books, 2006). It’s time to have a look at their findings, so brace yourselves dear readers as this will be one hell of a long ride! Contents follow:

Another important issue regarding the Holocaust is the awareness of the German public about it, either civilians or soldiers. What did the Germans know? Two researchers, historian Eric A. Johnson and sociologist Karl-Heinz Reuband, started searching for answers in 1993. After nearly 3,000 written surveys and 200 interviews the result was the book What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder, and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany (Basic Books, 2006). It’s time to have a look at their findings, so brace yourselves dear readers as this will be one hell of a long ride! Contents follow:

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Part One: Jewish Survivors’ Testimonies

1 Jews Who Left Germany before Kristallnacht

2 Jews Who Left Germany after Kristallnacht

3 Jews Who Were Deported from Germany during the War

4 Jews Who Went into Hiding

Part Two: “Ordinary Germans’” Testimonies

5 Everyday Life and Knowing Little about Mass Murder

6 Everyday Life and Hearing about Mass Murder

7 Witnessing and Participating in Mass Murder

Part Three: Jewish Survivors’ Survey Evidence

8 Everyday Life and Anti-Semitism

9 Terror

10 Mass Murder

Part Four: “Ordinary Germans’” Survey Evidence

11 Everyday Life and Support for National Socialism

12 Terror

13 Mass Murder

Conclusion: What Did They Know?

The authors not only interviewed Germans but also Jews, including eventually 20 interviews of each group, while changing the names of the interviewees to safeguard their anonymity. So we open the book and ask: What did you know about the mass murder of the Jews?

The Jews

We begin with Margaret Leib who, before fleeing to the US in 1941, was involved in communist resistance activities in Berlin.

“Before 1941, you hadn’t heard anything. Between 1942 and 1945, I was already here [in America]. I arrived here with great difficulty with my mother on September 12, 1941. My mother had gone to France right after my father’s death. My sister was nine years younger than me. She was killed. [While] they were still in Marseilles, she had a baby. Eventually she couldn’t feed her child any longer and she didn’t want to go on anymore. So she took the child to a children’s home. Then she was picked up during a raid and sent to a temporary camp in Nancy, and from there to Poland and the gas chamber. That she was deported is something I only know about from books.” (p. 13)

Only from books. No comment necessary. Next, Henry Singer, who fled to Italy in 1938. He doesn’t seem to know much as he states only the following:

“It’s not only the Germans that hated Jews. Almost the whole world hated Jews. The concentration camps – Auschwitz, Dachau, Buchenwald – Britain knew about it, France knew about it, the Americans knew about it. They could have done something about it. They could have bombed the camps because they were burning the bodies anyway. But they didn’t do it. You know why? Because they said, ’Leave Hitler alone because he’s doing a good job for us killing all the Jews. He gets the blame and we get what we want.’ That’s it in a nutshell, and nobody’s going to tell me any different.” (p. 18)

On the other hand he admits:

“But in all honesty I want to say that not all Germans were as bad as you see being depicted in the movies and the films. The majority was, but there were some that were not. So it’s not fair to accuse all of them.” (p. 17)

We now move to Rebecca Weisner who was sent to Auschwitz in October 1942 at the age of 16:

“We already knew by late July, August. One came from this camp, one came from that camp. Somehow we knew those things were more or less going on – that there was Auschwitz and that they had gas ovens to gas all the people, children and so. We knew that.” (p. 51)

Once again, they “somehow” knew. But Ernst Levin who was also deported to Auschwitz in January 1943, has a few more things to say (pp. 73-75):

“Word was filtering out. It was also filtering out that transports were leaving for the east from the ghettos. It was known at that time that these transports went directly to Treblinka or Auschwitz. Terrible, terrible! But people didn’t want to talk about it. When the German Jews learned about it, they really refused to believe a lot of it. The German Jews themselves would say, ’This is atrocity propaganda. That can’t be so. After all, it’s the twentieth century and we’re German.’ Many of them still considered themselves German. They didn’t believe it primarily because they didn’t want to believe it. Who can blame them? In Breslau the transports started in 1941. My grandmother had sisters, all of whom were sent on these transports. These people were taken away and they had nothing but their baggage. They left behind all their belongings, apartments, rooms, whatever they had. There were some vague rumors that they were going to the east to work. My grandmother’s sisters at that time were in their sixties. How were they going to work in the east? There were sick people. ’What is happening to them?’ they wondered. It was very disturbing, yet nothing was known for certain. Nobody knew of the gas chamber in Auschwitz at that time. Breslau had a very large Jewish community, the second or third largest in Germany. The only Jews left in Breslau at the end of 1942 were those who were integrated in the German war effort.”

He further adds:

“I was on the last transport when Breslau decided to become judenfrei [Jew free]. I think it was in January 1943. This German guy I was working with – he was actually a Meister, but he had not been drafted because he was already too old – then gleefully said: “Na ja, jetzt geht Ihr mal Steine kloppen in Russland!” [Oh yeah, now you are going to go break rocks in Russia!] I figured that this was going to be our fate. In general it was said that we were going to be relocated to the east – to work in the east. Just about four weeks before I went on my transport, there was one transport before mine and a friend of mine named Helmut went on that transport. That transport wound up in Treblinka. In a place near Treblinka, there was also a contingent of Germans working, one of whom we had known. Helmut wrote a letter and gave it to this man and said: ’Send it to my Ernst.’ I got this letter. I never knew who sent it or how they got it out. He told me in this letter that he was near Treblinka and ‘hier ist ein Lager, wo die Menschen chemisch behandelt werden.’ [Here is a camp where the people are being treated with chemicals.] It is amazing that even at that time he wouldn’t say that they were gassed. Isn’t that amazing? I was thinking, ‘What the heck does he mean?’ I guess he eventually was gassed. He certainly didn’t survive. Therefore I would have known four weeks before I was arrested that something was going wrong.”

Therefore, in a worksite near Treblinka his friend Helmut heard about people being “treated” with “chemicals”. Leaving aside the fact that he could even send a letter, this sounds more like a delousing procedure. As Levin himself thought, why didn’t he just say that they were gassed?

Next is Ruth Mendel, deported to Auschwitz in April 1943, when she was only 14 years old.

“As it turned out, women and children arriving in Auschwitz were gassed. But we were not. We were taken into Auschwitz and the other prisoners that had been there already knew their way around and said to us that the reason we weren’t gassed was that they thought, ’Well they’ll die soon anyway, so it doesn’t pay to run gas into the trains for just a few people.’ When we arrived, the SS was there with the dogs and the white gloves and the whips in their hands and beautifully pressed uniforms. At the time there were no selections. We were taken to the women’s camps.” (p. 87)

This shows how silly the rumors could be. Despite her age she was put to work on digging ditches. Here’s what she supposedly saw:

“That whole summer the crematorium was going day and night. During the day it was all smoke and at night you could see flames coming up. You could really see it. You could see it from miles away. In Birkenau I stayed with my mother the whole time in a big barracks, sleeping on boards with three pieces of straw or whatever that were infested with lice and fleas. I wouldn’t be alive if not for my mother. The crematorium was going and the flames were coming out. At night you would see it red. During the day it was black because of the smoke. There were little pieces, chips of bone, flying all over the place.” (p. 88)

We can be pretty sure that there is some poetic license here. And here’s how she left the camp:

“They put us on a train on November 1, 1944. We had no idea how we were picked to go on this train. Someone told us it was not to go anywhere – at the end of the tracks was the crematorium, a few yards or so away. But someone else told us, ’No, you are supposed to go to Germany as laborers.’ Of course you couldn’t trust this, but it turned out to be true.” (p. 89)

Well what do you know? Now it’s Helmut Grunewald’s turn who has some really interesting things to say. Born in 1918 to a Jewish father and a Catholic mother, he was deported to Auschwitz on March 1943. His father had been arrested by the Gestapo in 1942. Here’s what happened at the interrogation:

“This had all happened half a year before my arrest. But [when I was finally arrested,] my father was already there. While he was being interrogated [at Gestapo headquarters] by Bόttner and two other officers, he said to them, ’I don’t know why you want to interrogate me. I know that I’ll be sent to Auschwitz and be gassed anyway.’ […] But then they said to him, ’What kind of atrocity story is this that you are telling us? What makes you think that they are killing people there? How do you get that idea?’ ’Ah, you don’t have to tell me that,’ my father said. ’I know that. I know exactly what’s going on there.’” (p. 95)

But how did he know that?

“My father was extremely well connected, also in non-Jewish circles. That people were being murdered in Auschwitz and in Poland in general was evident anyway. And it was also already known that Auschwitz was very clearly an extermination camp.” (p. 96)

How about that. It was “evident”. Well, no matter how evident here’s the rest of the story. The Gestapo let him go!

“We believed it. We knew that it was true. It was just as my father had said to them when they had asked him, ’What makes you say that? What’s with this nonsense?’ He replied to them, ’You don’t have to tell me anything. I know that. So why do you want to interrogate me for so long?’ After this, they sent him back home to demonstrate that all of that was not true, and then my father went immediately into hiding. He went to the Eifel, to my grandfather’s birthplace, and was hidden there.” (p. 97)

Now Herbert Klein, deported to Theresienstadt in June 1943. In contrast to Grunewald, he claims that the Jewish community did not know of the mass murders. And as for the Germans he says:

“But nobody knew that [the Jews were being systematically murdered]. Nobody knew that because when my sister was deported from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz, first of all, we didn’t know it was Auschwitz. Still I’m sure certain things must have been known. When the Germans say they never heard anything, that’s a lie. One knew Dachau was a concentration camp. One knew they killed people. One knew that Sachsenhausen was a concentration camp. One knew about Buchenwald and about quite a lot of them. So, if someone said they didn’t know anything about it, that’s a lie. But if they say they did not particularly know that the Jews were murdered by the millions in Poland, that I accept. Even so, it is very difficult to accept.” (p. 107)

Next, Hannelore Mahler, deported to Theresienstadt in 1944. Asked when she first heard of the mass murders, she replied:

“That was actually more or less in the camp. In Berlin, one had whispered about it, and one was always questioning whether it was true or not. But nobody had dared to say anything openly about it, so it was still only a kind of assumption. That is the way that it is when you yourself are in a situation where you can be sent away on a transport at any time. You don’t want to believe it.” (p. 117)

Asked one more time, she replied:

“In effect, we knew nothing. Sure, we said, ’Where are they? What’s happened to them? And so on.’ But this was among ourselves, and afterward there wasn’t anybody left whom one could talk to. Yes, we suspected that those who had been sent away had not been sent to a sanatorium. But, since we ourselves could have been the next ones, or were – we were practically on the list to be mowed down – we didn’t want to believe it, because we could have been next. Do you understand what I am trying to say? We talked a lot about this afterward in retrospect. In retrospect, we said that we had suspected it and left it unspoken during the war. Everyone knew it. Everyone had thought that it was so. But we did not want to talk about it, because you could be there yourself. When one suspects that those who had been arrested and taken away and had never been heard from again, had not been sent to a sanatorium, you can almost compare that with someone who is about to be tested for cancer. One just doesn’t talk about it, even though everyone knows that it is so. Do you understand? One just doesn’t talk about it.” (p. 119)

Next are the testimonies of Jews who went into hiding and the first is Ilse Landau, who was arrested in 1943 for distributing leaflets in Berlin. She was sent to Auschwitz, but she managed to escape by jumping off the train. Her replies are worth quoting in full (the interviewer’s questions in bold):

“When did you first hear about the mass murder of the Jews? Was it before you were put on the train to Auschwitz or after that?

We had heard already that the other people were murdered in those other, nearer by, concentration camps like Bergen-Belsen and Sachsenhausen. There was a lot we had heard about.

When you were on the train going to Auschwitz, did you know that you’d go to Auschwitz?

Yes.

What did you know about Auschwitz at that time?

That they all would be gassed. Only a few who could work [might survive]. They were to dig the graves, cook for them, clean the toilets, or whatever there was to be done as work. That was the same as in Theresienstadt. My father died in Theresienstadt, and my aunt saw it with her own eyes that they had nothing to eat.

When did you first hear about the gassing of Jews and from whom?

That I can’t tell you.

Was it from other Jews, or from Gentiles, or from the radio?

From radio maybe. But I didn’t listen to the radio, my husband did. I went to sleep. I had to sleep. I wasn’t able to listen. A man is still stronger, you know.” (p. 125)

Another Jewess, Lore Schwartz, describes Theresienstadt and Auschwitz as transport camps:

“We did know, because we had worked before in those transport camps. The old people and the war wounded and the Jewish community employees went to Theresienstadt, so you knew that there was a preference, that there must have been something special about it. Auschwitz, I was there, so I knew. I was there as a visitor. I also knew that my father was in Buchenwald and that he died a few days after he was released. We knew that it was no picnic whatever was there. How much the Germans knew, I don’t know. But I can tell you that later on when I was in a work camp that you marched there in the wintertime without hair and without clothes. So they must have known, too. Definitely! If anybody tells me they didn’t, they did.” (p. 131)

Finally, Rosa Hirsch also claims ignorance on mass murders:

“In the beginning, you really thought they were going to work camps. I guess they didn’t want to admit it to themselves. Nobody knew for sure. I mean, at least nobody of the people I knew. We knew that it was something horrible. When the mail came back from my aunt’s with address unknown, we knew they were not alive anymore. But nobody knew about gassing. I don’t think anybody knew that. I mean, maybe they thought they died of hunger or maybe they died of something else. We didn’t know.” (p. 137)

This concludes the Jewish testimonies.

The Germans

We begin with Hubert Lutz who was born in 1928 and was a member of the Hitler Youth from ages 7 to 17. Regarding the murder of Jews he first states:

“We heard about a transport of people going out. There were rumors that people were killed, but there was never any mention of gas chambers. There were rumors that said people were squeezed together in these camps and most died of typhoid fever. And that was in essence the execution style. Now, about shootings, that was in connection with the partisans. Nevertheless, I am sure that they rounded up Jewish people and executed them along with the other partisans. I didn’t really give it any thought. I was fifteen, sixteen years old. We heard this on the periphery. That was not, to kids of my age at the time, our primary interest.” (p. 147)

Then follows this:

“When did you first hear that Jews were being murdered in great numbers?

In great numbers, I would say 1948, 1949. We knew about concentration camps. In 1945 after the war there were a lot of people running around and showing their numbers, their tattoo numbers. There were some pictures that were shown right at the end of the war, like when they liberated Dachau, Buchenwald. But that to us was almost understandable because the pictures they showed were of people that had obviously died from starvation. You could see their skeletons. We had not been through that kind of a starvation, but we knew how quickly you lose your weight. And there was also the word that most of these people had died from typhoid fever. And there were many other typhoid cases, for instance, in France and in Buchenwald. So, yes, that was not excusable. On the other hand, there were times at the end of the war when a lot of our people didn’t have anything to eat.

What about the gassing and the shootings?

We tried not to believe it. We simply said, ’No, that’s too brutal, too gruesome, too organized.’ Quite frankly, I began to read more and study more about it when I was in this country after 1959. A lot of people asked me, ’How come you guys didn’t know this? You claim you didn’t know anything about it.’ And, I asked myself, ’Well, how come you didn’t know this?’ So I started reading a lot and I started, well, maybe reading with a biased mind, hoping that I would find reason to believe that it was not true. But the evidence piled up. This became more convincing by the day. So I also asked myself, ’Could we have done anything different? Where did the responsibility lie?’ My conclusion was the responsibility lies in the fact that people didn’t do anything about it. They just stood by and closed their eyes and ears. And I think that is true. People just didn’t want to believe it. They didn’t.” (p. 150)

Now a daughter of a former policeman, Gertrud Sombart, who lived in Dresden during the Nazi period had this to say:

“Did you know anything about the mass murder of the Jews?

Not about the mass murder. We heard from my mother, who had heard from a female patient at the hospital, that there were such camps. But we thought they were labor camps because one had put them to work in the war industry. Nevertheless, she had provided some hints about that, but not anything specific. We did, however, get some more specific information from an acquaintance of ours. He had been working at a large power plant in Poland. He wore the Order of Blood decoration, which was for those who had been with the Nazis from the very beginning. Nevertheless, he was basically a good man, hardworking and industrious. We were friends with him and he knew what our views were. He would never trick us. While he was over there in Poland, he had seen how Jews were forced to shovel out ditches and were then shot. After that he said to himself that he was not going to go along with that, and then he returned [to Dresden] and talked about this.

But you apparently didn’t know until after the war that people were being killed in those camps?

Yes. There was, however, the time when I did see this one group. They were Jews and had probably been in such a camp. That was here in Dresden. Nevertheless, there were around fifty of them at least. They looked like starving wretches, haggard, and were merely able to shuffle themselves along. The population thought they were criminals. They looked like criminals.” (p. 161)

Next, Anna Rudolf who worked in Berlin at a film duplication laboratory:

“Did you know before the end of the war about the concentration camps?

No. You would often hear things like, ’He has been taken to a labor camp. He did something and he’s been taken to a labor camp.’ But everything was covered up and kept concealed. Nobody knew anything specific. And then we’d hear again, ’They packed that guy off to Dachau.’ My parents had thought that Dachau was a labor camp until it got around what kind of camp it really was. After that, everybody was afraid and nobody dared say to anything.

Did you know from rumors before the end of the war about what had happened to the Jews?

Yes, even already during the war. That was all certainly talked about. But, as I was saying, it was always just said, ’They are going to a labor camp.’ That they were gassed, and so forth, nobody had thought that. Nobody had thought that. Afterward, after the war, I worked with a Jewish woman whose father was a tailor. Her entire family had been taken away and her father had been forced to make and mend clothes in a concentration camp. But her brothers and her sister and her mother were all gassed. She herself had been hidden and so both she and her father survived. Anyway, she told me all about what went on there, how they were beaten, and how they had to do all that work. That was certainly horrible.” (p. 170)

It’s the same old story all over again. Someone was put to work while the rest of the family was gassed.

Peter Reinke follows, the son of a plasterer, born in 1925. He joined the navy in 1942 and he stated the following:

“While you were in the military, did you hear anything about the concentration camps or the deportations?

No, no. Not much. Not much. It was said that the Jews who hadn’t been deported had been made to work. That was what the [Nazis] had publicly told the people. What was done there, nobody knew. But we did indeed see how concentration camp prisoners had been forced to work, such as, for example, the Hiwis. These were Russians, White Russians, or Ukrainians, who had to carry out all sorts of functions. They had to work. They had to load and unload and perform all the menial tasks that needed to be done anywhere in the Wehrmacht, in any unit.

Did you ever hear any rumors or other things about mass executions?

No, no. I didn’t know about that. During the war we didn’t hear anything about that. We were seldom on land, only for loading up supplies. [But there was this one time] when we were in Libau [Latvia]. The naval base lay outside the city – at the point where the open territory began – and there was a lot of shooting. Then a rumor went around that they were shooting Russians. But then, we knew that the Waffen SS didn’t take any prisoners when they were dealing with the Russians. On the other hand, Waffen-SS men were shot by the Russians. There was so much shooting going on in the area – the front was only fifteen kilometers away – that you couldn’t really tell who was shooting whom and where the shooting came from.” (p. 176)

Next is Werner Hassel, who grew up in Upper Silesia, and listened to the BBC both at home and in the military. Yet he knew nothing about exterminations (p. 182):

“The soldiers out there on the front knew effectively nothing about the concentration camps and the mass murder of the Jews. I cannot imagine that [they had known]. I would have been aware of that. Especially since I came from a very different political past, I would have heard about that. A large number of people really didn’t know anything. I myself didn’t know where Sachsenhausen was or Auschwitz. That really was only known by people with inside information. When we were in Poland, we heard absolutely nothing [about the murder of the Jews], no rumors, absolutely nothing.”

Now let’s hear Hiltrud Kühnel, a student of dentistry during the war at the University of Frankfurt. Pay attention to her replies, one by one:

“Back then, what did you imagine concentration camps to be?

Extermination camps. That’s what I imagined concentration camps to be.

You didn’t simply think of something like a labor camp?

No, no. Extermination camps! You knew that was what they were. Hence, if someone says today that he had never known that, it is absolutely not true.

Do you mean to say that not only you knew about that but others did as well?

That was known by others as well.

How did one know that?

From the circle of acquaintances that you had, from the clergy and from good friends who shared our political views. It was talked around about what they were doing there. Those were indeed real extermination camps.

When did you hear about extermination camps for the first time? Can you give an exact date?

That must have been 1938 to 1939 at the time of Kristallnacht. That was in November 1938. We were sent home from school. That morning our school principal said to us, ’Please go home immediately, all of you. Horrible things have happened.’ I had to go back home with my schoolmate, from Frankfurt to where I lived in Hochst. Anyway, that was horrible for me. They had taken the cakes from Jewish pastry shops and thrown them onto the street. They cut open the Jewish families’ down blankets. There were a lot of Jews in Frankfurt. You could see the feathers floating around in the street. The cigars, the pipes from the tobacco shops, everything was lying in the street. The windowpanes were smashed in. I came home crying. We really could only cry. And then we said, ’Those are beasts. Human beings don’t do things like that.’

But that isn’t exactly the extermination of human beings.

No, but that was the beginning of the disregard of a race. They classified them as inferior. I would say that is when one started to know about it all. But, for heaven’s sake, you weren’t allowed to talk about it.

But how did one hear about it then, if one wasn’t allowed to talk about it?

For example, from a clergyman who was often at our place and from some others, whose names I can’t recall, who said, ’We heard that…’ That’s how.

But what had they heard exactly?

That the Jews were being gassed, and the foreigners. Indeed, one knew about the gassing.

One heard this expression exactly?

Gassing. Yes.

That they were being gassed, you heard this from clergymen? In your own home?

Yes, in our home. I already said that this was a kind of meeting place that the Nazis were aware of. They were aware that anti-Nazi groups were still meeting with my father.

Did you hear about this from the clergymen yourself?

Yes. Politics was the only thing they discussed at our place, whether it was over lunch or otherwise. I can really only recall political conversations at our home. That’s how I grew up. The clergymen knew that at our place they would never be named as a traitor or anything like that because of what they had made known there.

I wonder how the clergymen got their information. Did they say how they found out?

No, they didn’t tell us that. It only came up in the course of conversation as yet another atrocity that was known.” (pp. 187-189)

On to Ruth Hildebrand, the daughter of a civil servant in Berlin. Regarding the concentration camps she knew the following:

“Only that the Jews were being sent there. That the Jews were being gassed, they didn’t say. They didn’t go as far as that. The soldiers who had escorted the trains with the Jews had to get off just before the gates [of the camps], and then they rode back again with the train that was now empty. That’s what they said, and my husband told me about this late one evening. It depressed him so. It weighed heavily on him, and also, of course, on me. That they were gassed came out later. It did leak out slowly, however, that they had somehow met their death there. But one did not hear anything specific.” (p. 194)

On these rumors about the camps, Ekkehard Falter from Dresden comments:

“One knew that there were concentration camps. The Dresden members of the Communist Party were incarcerated at the Hohenstein Castle. In 1933, after the Nazis took power, they were collected there, and the population of Dresden knew that there was a concentration camp where members of the Communist Party were incarcerated. At that time there weren’t any concentration camps where Jews were being held, unless they were politicians. Only in 1943 did it become clear to me that Jews were being incarcerated in large numbers. They disappeared without any ado, picked up one by one. I knew that there was a special stratum of Jews here in Dresden that was richer than others who had pensions or had emigrated. But in the inner city, there were also poorer Jews from sections of the city where less affluent people lived because rents were cheaper. They didn’t have the money to emigrate.” (p. 198)

Asked when he heard for the first time about the mass murders, the only thing he knew about was the mass shootings as he had learned from an SS sergeant:

“At night he would tell me about things they had done. Because it was all so horrible I couldn’t sleep anymore. It would be a chapter in and of itself, and I don’t now want to talk about what he and his combat unit did to the population, like hoisting them up into the air with their feet and then shooting them. He told me that he didn’t understand how that could have happened. He said that there had been people with them who had passed their university qualification exams and had come from solid middle-class homes, but in only half a year they had been reeducated to the point that they no longer were bothered by what they were doing. [For example,] they had rounded up all the people in a Polish village, women and children, locked them up in a church, and then shot at them from the church’s gallery before setting the church on fire. ’We then lay around the church in radiant sunshine while the church burned. Those who had not gotten out were screaming, and then the door suddenly opened and a small child came out. One guy then got up, rat-a-tat-tat, dead. [Having been involved in all of this,] can you imagine that I am now going to remain here?’ And then, with the pin that had been just implanted in his leg and in a cast, he got up and took off. He even told me about things that were still worse. I don’t want to talk about them here. They are that dreadful.” (p. 199)

Stefan Reuter from a working-class family in Berlin, was asked if he had heard what was happening to the Jews during the war. Here’s his response:

“No, as crazy as it is. Sure, it was talked about, but I didn’t have any solid proof. At the time when my wife was to be picked up, one heard in communist circles that numbers of Jews were being gassed. There were these rumors, but there was no direct proof. After all, one can talk a lot. My thoughts leaned more toward the view that it could really have been possible.” (p. 203)

Then we have Ernst Walters, from a small town in the Saar region, who became a Nazi Party cell leader in 1937, and declares that he was already aware of the fate of the Jews in 1935. After this he states the following:

“[During the war] my parents [were evacuated and] were in Hameln and I somehow got the news that they were there. Since I had my motorcycle, I decided to drive there – I even had somebody riding on the back of the motorcycle with me. And then on the way back, we drove through Thuringia. I don’t know what town it was, as I didn’t take notice of it. But, anyway, we made a stop there and the place was stinking: ’What is that smell?’ ’Over there is a concentration camp, that’s where the corpses are being burned, where soap is being made from the Jews.’ In the concentration camps, [there were] Jews, and not only Jews. There were also communists. And there were also some in our town who disappeared. There were some who disappeared who were sick. That [all] was managed by the party. The party had them disappear.” (p. 208)

Weird smells were enough for the imagination to go wild. But in the end, everything turns out to be endless hearsay. Effie Engel was from a working-class family with communist leanings in Dresden. Here’s how she learned about the mass murders:

“I heard about this from my mother, who had heard about it from her friend – they were actually not supposed to talk about it, as it was all strictly confidential. Just before the end of the war, he was given leave and he came to visit us and he said, ’Listen, I have to tell you this. I can hardly stand it any longer. It is impossible how those people are being abused there. They have driven them down into those tunnels and forced them to work under SS supervision, and one after another of them is dropping dead because they simply don’t get enough to eat.’ And then he also went on to tell us about how they had been in camps, and about how they were so decimated that there were ever fewer and fewer of them. Only the strongest were sent to work; the others were annihilated. That was something he knew about already, and that was how I heard about it.” (p. 218)

Winfried Schiller was from the city of Beuthen in Upper Silesia. His father was a doctor and had some connections with Auschwitz which was not far from them:

“In any event, Auschwitz was less than one hundred kilometers from us. Every now and then, one thing or another got through to us about how the Nazis had numerous people in the camp. But, about the actual gassing or the elimination of the Jews, that was not known right up until the last days of the war. But that the Nazis interned people there, that the camp was full of people, that was definitely known.” (p. 222)

Regarding the rumors he adds:

“Only in the last years of the war was when the rumors got through about things like the concentration camp inmates being tortured and that they were dying so wretchedly. About the actual consistent gassing, we did not know. Then, when the Russian invasion came and the German army had to retreat, the concentration camp was evacuated. Then there came a great flood of concentration camp inmates in their striped clothes. It ran through Beuten toward Silesia. It was only then that the extent really became known.” (p. 223)

Next witness, Αdam Grolsch, a radio operator in the German army on the Russian front. Asked about the mass murder of the Jews, he first spoke of a mass shooting of 25,000 Jews in Pinsk within two days in October 1942. This was done on German orders but by Cossacks, Lithuanians and Latvians. Although the shootings are a fact, the number he claims is way too high to be believable.

Anyway, he was finally asked if he had heard BBC reports about gassings, to which he replied:

“Yes, I heard that as well. I can still remember this because I later saw those [gas] vans. But I heard about it too. I had by chance seen those vans. They were parked in Rowno [Rivne] and nobody knew what they were. They were those large and long mobile trailers attached to trucks. That is to say, they were mobile gas chambers for smaller operations. My attention was drawn to it by the BBC. Where I saw it was in Rowno. Rowno was in the middle of the Ukraine. But previously we had heard about such things from the BBC, like about mass shootings of Russians. That was what I knew about the best. They had also explained how they had also done that with small groups [of people] and with such vehicles as well. That was such a thing to hear that you wanted to see for yourself if that was really the case. And then I ended up seeing two or three of those things in Rowno, parked near the harbor. I often had to go to Rowno to get replacement parts for the radio post. That could have been in 1943.” (p. 237)

But according to the official story, those mobile gas chambers were single trucks, not the long trailers attached to trucks. And of course, he never witnessed any of them in operation. He only made the connection because of the BBC.

So finally, we arrive at the last witness, Walter Sanders, who was a communications officer on the Russian front. He concludes his interview with the following:

“For the sake of those who say today that they didn’t know anything about it – a large part of the population did know about it. Perhaps [they didn’t know] that it was quite as brutal as it was in reality. But they knew that there were concentration camps. They knew that Jews were kept there. And later, word got around that they were gassed. It wasn’t for nothing that it was said in those years, ‘Take care, otherwise you’ll go up the chimney.’ That was a familiar figure of speech. It circulated everywhere in Germany. [An expression like] ‘otherwise, you’ll go through the chimney’ doesn’t come about by chance.” (p. 259)

Nope. Not by chance. But a figure of speech it was.

Summary

From the revisionist viewpoint, not one of the above statements is unexpected or unprecedented. They all add up to the point that the rumors about mass killings were running wild, although not everyone had heard about them or believed them. They also illuminate the mindset of those who did believe them, some of them almost religiously. Of course, there were hard labor and mass shootings. But after decades of research, it can be stated with certitude that it is the extermination story that has gone up the chimney.

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, Vol. 10, No. 2 (2018)

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a