Zyklon B – a Supplement

Zyklon B is the term of horror that symbolically summarizes all the atrocities reported about the National Socialist era. For the majority of people today, Zyklon B is the epitome of industrial mass murder. However, this will not be discussed here. Rather, after a brief description of the history of its creation and regular use, some of the physical and chemical properties of this product will be discussed.

Hydrogen cyanide (HCN) was already used sporadically at the front as a combat gas during the First World War.[1] Like all combat gases, it was developed under the direction of Fritz Haber, who – ironically – was a baptized Jew. It was he who, after the war was lost, made the control of pests, such as lice, bugs, beetles, rodents etc., the main area of application for poison gases. He introduced the hydrogen-cyanide fumigation process, which had long been used in the USA, to Germany. He replaced the risky US method – in which someone poured a cyanide salt into a container filled with a liquid acid in the so-called “vat method,” and then immediately withdrew – with a safer method in which anhydrous hydrogen cyanide, mixed with a stabilizer and a lacrimatory warning substance, is absorbed by a porous carrier material and packed airtight in a can.[2] When the can is opened, the adsorbed hydrogen cyanide evaporates more or less slowly from the carrier. Fritz Haber founded the Technical Committee for Pest Control (Technischer Ausschuß Schädlingsbekämpfung) in the spring of 1917, which later became the Frankfurt-based Deutsche Gesellschaft für Schädlingsbekämpfung (DEGESCH; German Association for Pest Control), the later main licensor of Zyklon B, which also supplied this chemical to the SS.[3]

However, both the judiciary and the scientific community have now recognized that there was nothing criminal behind these deliveries. For example, the Federal German judiciary acquitted Dr. Gerhard Peters, the main person responsible for the production and distribution of Zyklon B at the time, as well as all others accused in this connection, because it could not be demonstrated that they must have been aware of the misuse of their product.[4] This verdict is based on the findings of the judiciary and the scientific community that, during the Second World War, DEGESCH supplied not only private customers but also many authorities of the Third Reich and of its allied countries with tons of Zyklon B: the civil administration, the various armed forces, the Waffen-SS and the ordinary SS were supplied with the product throughout Europe. It is undisputed that the Auschwitz Camp, for example, did not receive any more Zyklon B than other concentration or prisoner-of-war camps, such as Buchenwald or Bergen-Belsen, in which it is recognized that no mass murder with Zyklon B took place. For example, during the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg, the Allies presented documents from a file proving the delivery of considerable quantities of Zyklon B to Auschwitz. However, they concealed the fact that the same file also contained documents with similar deliveries to the Oranienburg concentration camp north of Berlin, where no one has ever claimed that there were human gas chambers.[5]

The internationally renowned researcher Jean-Claude Pressac has also established, in agreement with the prevailing opinion, that around 95-98% of the Zyklon B delivered to Auschwitz was used for nothing other than its originally intended purpose: to destroy pests such as lice and bugs for hygienic reasons.[6] In other words, the amount of Zyklon B allegedly used for mass murder is statistically unverifiable and therefore simply claimed without proof.

The frequent misinterpretation of the fact of Zyklon B mass deliveries to Auschwitz as proof of mass murder is due to the fact that the uninformed are not made aware by the orthodox accounts of Zyklon B’s central role in pest control in Europe until the end of the Second World War. They are also not told how desperately the Wehrmacht, Waffen-SS and SS struggled against epidemics such as typhus among the fighting troops, in prisoner-of-war and concentration camps. As these epidemics were mainly transmitted by lice, the killing of lice was the primary goal of all hygiene measures in the various camps. However, the most effective agent for this at the time was Zyklon B. The main purpose of this agent was therefore not to kill the masses, but to prevent mass deaths. The product therefore has this terrible image quite wrongly. F.P. Berg has reported in detail on the importance of Zyklon B especially for the Axis powers’ entire hygiene and health care system, which should not be underestimated.[7] Contemporary literature describing the importance of Zyklon B is extensive, but is generally ignored in orthodox depictions of the time.[8] Zyklon B continued to play an important role for some time after the war before it was replaced by DDT and its successors.[9]

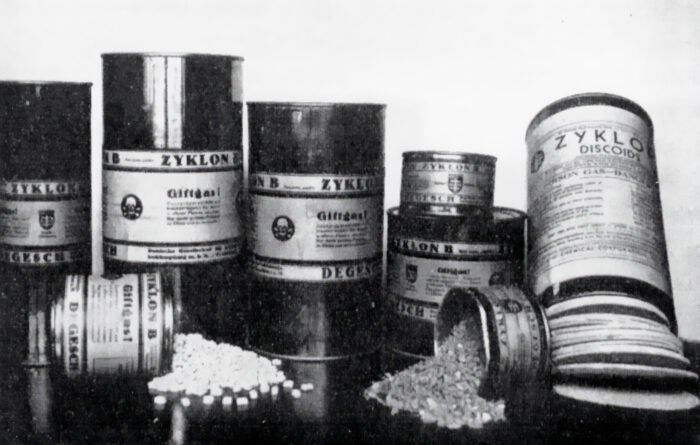

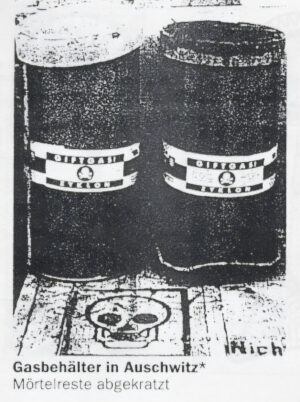

Zyklon B exists or existed at times with three different carrier materials: diatomaceous earth in granular form, grain diameter smaller than 1 cm (Diagrieß), a carrier material made of gypsum (Erco) available in granular or cube shape, or cardboard discs made of porous fiber material (discoids), similar to beer coasters with a hole in the middle.

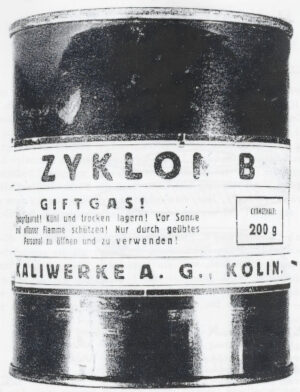

At the beginning of the development of Zyklon B, the carrier material consisted only of diatomaceous earth.[10] At the end of the 1920s, DEGESCH commissioned the Chemisch-Technische Reichsanstalt to investigate whether diatomaceous earth could be substituted by gypsum as a carrier material.[11] The investigations showed the advantages of gypsum over diatomaceous earth, so that it can be assumed that in the following years diatomaceous earth was gradually replaced by gypsum-containing substrates. Further interesting reports on this subject may be contained in the 1931-1944 volumes of the Reichsanstalt, but I could not locate any copies of them anywhere in Germany. It is possible that these documents were transferred to an Allied archive after the war. R. Irmscher from DEGESCH reports in an article published in 1942 that at that time the use of fiberboard discoids and gypsum (Erco) as carrier material was standard.[12] The director of DEGESCH, Dr. Gerhard Peters, reported after the end of the war that the Zyklon B produced by the Dessau Sugar Works (Dessauer Zuckerwerke) had been applied to a starch-containing gypsum carrier.[13] It is clear from another context that the fiberboard carrier material was later preferred.[14]

In the period from 1942 to 1944, which is important for many people interested in contemporary history, it is therefore highly probable that the diatomaceous-earth version (Diagrieß) of the 1920s and early 1930s was no longer used, but that the gypsum (Erco) version was preferred at that time.[15] In today’s product, whose name was changed to “Cyanosil®” a few years ago, approximately 60% of the product’s mass is accounted for by the carrier mass, which can also be assumed to be of a similar order of magnitude for the product used at that time. [16]

The evaporation of the poison gas HCN (hydrogen cyanide) from the carrier varied greatly depending on the carrier material. In the mid-1920s, the Zyklon-B carrier material consisted almost entirely of diatomaceous earth, which, according to the patent application, almost completely released its hydrogen cyanide within ten minutes.[10] In the early 1930s, G. Peters stated that the majority of the adsorbed hydrogen cyanide was released within half an hour, if the preparation was spread out in a layer 0.5 to 1 cm thick,[17] although it is not clear exactly what material the carrier was made of.

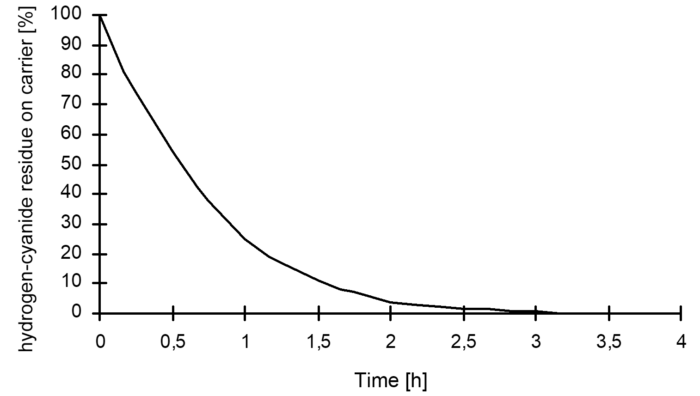

Evaporation times longer than those mentioned by Peters in 1933 were evidently achieved in the following years, probably by constantly increasing the proportion of gypsum in the carrier material to increase storage stability (and – incidentally – also to reduce the price of the carrier material), because the hydration water contained in gypsum binds hydrogen cyanide more firmly than the diatomaceous-earth version. For the Erco version of 1942, R. Irmscher gives an evaporation chart for 15°C and low humidity as given in Figure 1. At high air humidity, this evaporation can be considerably delayed, as the evaporating hydrogen cyanide draws considerable amounts of heat from the ambient air and thus condenses out air humidity on the carrier, which in turn binds hydrogen cyanide.[12]

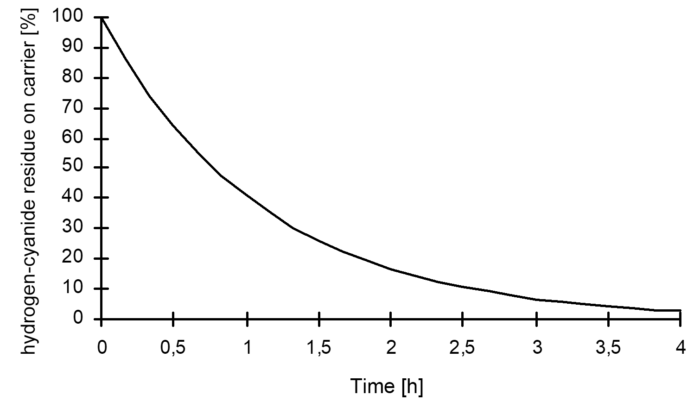

Similar, albeit somewhat less precise, information can be obtained about today’s products. According to information from the Linz-based pest control company ARED, the hydrogen cyanide it uses, which is adsorbed onto fiberboard disks, takes between 1 and 6 hours to be released, depending on the temperature.[18] Another piece of information comes from Detia Freyberg GmbH, a successor company to DEGESCH, which was the main supplier of hydrogen-cyanide products until the end of the war.[16] As the release of gas depends on temperature and air movement, Detia Freyberg GmbH only gives a rule of thumb. According to this rule, the unspecified carrier releases 80 to 90% of hydrogen cyanide within 120 minutes at a temperature of more than 20°C and uniform distribution of the preparation. After 48 hours, no or only negligible hydrogen cyanide residues can be detected in the carrier. At lower temperatures, this process should slow down in accordance with the falling vapor pressure of hydrogen cyanide.[19] Assuming an exponential decrease of hydrogen cyanide in the carrier, the characteristics shown in Figure 2 were derived from this data. According to this, 50% hydrogen cyanide release can be expected after 40 to 45 minutes (120/3 min).

For the Zyklon B preparation probably used in the period between 1942 and 1944, it can therefore be assumed that at 15°C and low humidity, about 10% of the hydrogen cyanide left the carrier substance during the first five minutes of the preparation being laid out and about 50% after half an hour. In cool cellars, such as the morgue cellars of crematoria II and III allegedly used as homicidal gas chambers in Auschwitz-Birkenau, with naturally high humidity, the evaporation time would have increased accordingly.

Rudolf has already reported in detail on the consequences of this rather slow release of the poison gas with regard to the credibility of contemporary historical claims.[21] These findings are substantiated by Friedrich P. Berg.[1]

In addition to the carrier material, the composition of the active ingredients apparently also changed somewhat in the later years of the war. We know that, from around 1943 to 1944, Zyklon B was also produced without a warning agent, and supplied as such in large quantities to Auschwitz, for example. The DEGESCH invoices of February 14, 1944 to SS Obersturmführer Kurt Gerstein, submitted to the IMT, are famous in this regard:[5]

“Today we shipped the following consignment by rail from Dessau […] to the AUSCHWITZ concentration camp, Disinfestation and Decontamination Department, station: AUSCHWITZ, as express goods: ZYKLON B Prussic acid without irritant = 13 crates, containing […] = 195 kg CN […]. The labels bear the note ‘Caution, without warning substance.’”

Degesch was only the licensor of Zyklon B. The product itself was manufactured by several companies, among them the Kaliwerke A.G. Kolin and the Dessauer Zuckerwerke, each with their own type of labels. Sales were arranged by two distributing companies: The Heerdt-Lingler Company (Heli) of Frankfurt for territories west of the river Elbe, and the Tesch & Stabenow Company (Testa) of Hamburg for Scandinavia, east-Elbian Germany and Eastern Europe.

However, the frequent interpretation of this fact as proof that it was allegedly intended for mass murder[22] is incomprehensible, as it is not clear why a special product should have been produced for mass murder. Rather, it can be assumed that the chemical industry was severely damaged by the Allied air raids on German conurbations, so that a reliable supply of this warning substance to the Zyklon-B producers was no longer possible. However, the Zyklon B producer responsible for Auschwitz, the Dessauer sugar refinery located south of Magdeburg (hydrogen cyanide was obtained from the residues of sugar refining), was never affected by the air raids. It is therefore only logical that the warning substance was partially dispensed with in the later years of the war in order to meet the constantly increasing demand for hydrogen cyanide to combat epidemics. This is especially true in view of the fact that the warning substance is in principle superfluous for the functionality of the product, and is only added for safety reasons.

It should be noted that, by decree of April 3, 1941, hence many months before the alleged decision on the “final solution of the Jewish question,”[23] which was not backed up by documentary evidence, and before the alleged consideration of the use of Zyklon B for mass murder,[24] the Waffen-SS was exempted from the obligation to comply with Reich regulations and implementation decrees regarding pest control with highly toxic gases.[25] This exemption cannot be explained by the fact that it was intended to facilitate mass murder and make it administratively possible, as there were no such plans at the time. This decree was probably issued to enable the Waffen-SS to fight pests and the resulting epidemics, bypassing possibly obstructive regulations. This was possibly done with a view to the already planned Russian campaign, as it was known from experience in the First World War that epidemics in the East were often more dangerous than the enemy.

Notes

First published as “Zyklon B – eine Ergänzung” under the pen name Wolfgang Lambrecht in Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung, Vol. 1, No. 1 (1997), pp. 2-5.

| [1] | For the toxicological effects on humans, see Fritz Berg, “The Self-assisted Holocaust Hoax,” October 1, 1996; https://codoh.com/library/document/the-self-assisted-holocaust-hoax/; see the updated version in this issue. |

| [2] | The predecessor of Zyklon B, Zyklon A, consisted of a liquid mixture of cyano-carbonic acid ester and chlorinated carbonic acid ester with irritants; see K. Naumann, “Die Blausäurevergiftung bei der Schädlingsbekämpfung,” Zeitschrift für hygienische Zoologie und Schädlingsbekämpfung, 1941, Vol. 33, p. 37. |

| [3] | On Fritz Haber’s activities see A.-H. Frucht, J. Zepelin, “Die Tragik der verschmähten Liebe,” in: E.P. Fischer, Neue Horizonte 94/95. Ein Forum der Naturwissenschaft, Piper. Munich 1995, pp. 63-111. |

| [4] | Degussa AG (ed.), Im Zeichen von Sonne und Mond, Degussa AG, Frankfurt/Main 1993, p. 148; the daily newspaper Wilhelmshavener Zeitung, Oct. 2., 1987, remarks on this with a tone of indignation that can only have been caused by ignorance. |

| [5] | IMT Documents 1553-PS; cf. David Irving, Nuremberg: The Last Battle, Focal Point, London 1996, p. 151 and document section, p. 12. |

| [6] | J.-C. Pressac, Auschwitz: Technique and Operation of the Gaschambers, Beate Klarsfeld Foundation, New York 1989, pp. 15 and 188. |

| [7] | F.P. Berg, “Typhus and the Jews,” Journal of Historical Review, Winter 88/89, Vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 433-481; idem, “The German Delousing Chambers,” ibid., Spring 1986, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 73-94. |

| [8] | As it is impossible to cite the entire literature here, but only a selection of interesting topics, please refer to further literature cited in them: O. von Schjerning, Handbuch der Ärztlichen Erfahrungen im Weltkrieg 1914/1918, Vol. VII: Hygiene, J. A. Barth Verlag, Leipzig 1922, esp. pp. 266ff: “Sanierungsanstalten an der Reichsgrenze”; O. Hecht, “Blausäuredurchgasungen zur Schädlingsbekämpfung,” Die Naturwissenschaften, 1928, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 17-23; G. Peters, Blausäure zur Schädlingsbekämpfung, Ferdinand Enke Verlag, Stuttgart 1933; idem, W. Ganter, “Zur Frage der Abtötung des Kornkäfers mit Blausäure,” Zeitschrift für angewandte Entomologie, 1935, Vol. 21, No. 4, pp. 547-559; W. Scholles, “Die Bekämpfung der Blutlaus durch Blausäure,” Der Obst- und Gemüsebau, 1936, pp. 3ff.; K. Peter, “Der Hafengesundheitsdienst in Hamburg,” Reichsgesundheitsblatt, 1936, pp. 430-434 (Zyklon-B fumigations of ships); G. Peters, “Ein neues Verfahren zur Kammerdurchgasung,” Zeitschrift für hygienische Zoologie und Schädlingsbekämpfung, 1936, Vol. 28, pp. 106-112 (Introduction of the novel circulation method); idem, “Durchgasung von Eisenbahnwagen mit Blausäure,” Anzeiger für Schädlingskunde, Vol. 13 (1937), pp. 35-41; idem, “Entlausung mit Blausäure,” ibid., 1939, Vol. 31, pp. 317-325 (of special interest: furniture vans as makeshift delousing vehicles; witnesses sometimes report furniture vans as mobile human gas chambers, see Ingrid Weckert, in: G. Rudolf (ed.), Dissecting the Holocaust, 2nd ed., Theses & Dissertations Press, Chicago, IL,, 2003, p. 238); R. Wohlrab, “Flecktyphusbekämpfung im Generalgouvernement,” Münchner Medizinische Wochenschrift, 1942, Vol. 89, No. 22, pp. 483-488; G. Peters, Die hochwirksamen Gase und Dämpfe in der Schädlingsbekämpfung, F. Enke Verlag, Stuttgart 1942; DEGESCH, Acht Vorträge aus dem Arbeitsgebiet der DEGESCH, 1942; F. Puntigam, H. Breymesser, E. Bernfus, Blausäuregaskammern zur Fleckfieberabwehr, Sonderveröffentlichung des Reichsarbeitsblattes, Berlin 1943; F.E. Haag, Lagerhygiene, Taschenbuch des Truppenarztes, Vol. VI, F. Lehmanns Verlag, Munich 1943; W. Dötzer, “Entkeimung, Entwesung und Entseuchung,” in: J. Mrugowsky (ed.), Arbeitsanweisungen für Klinik und Laboratorium des Hygiene-Institutes der Waffen-SS, Issue 3, Urban & Schwarzenberg, Berlin 1944; F. Puntigam, “Die Durchgangslager der Arbeitseinsatzverwaltung als Einrichtungen der Gesundheitsvorsorge,” Gesundheitsingenieur, 1944, Vol. 67, No. 2, pp. 47-56; W. Hagen, “Krieg, Hunger und Pestilenz in Warschau 1939-1943,” Gesundheitswesen und Desinfektion, 1973, Vol. 65, No. 8, pp. 115-127; ibid., 1973, Vol. 65; no. 9, pp. 129-143; NMT Document NI-9098, property table of gaseous insecticides carried by DEGESCH; |

| [9] | H. Kruse, Leitfaden für die Ausbildung in der Desinfektion und Schädlingsbekämpfung, Muster-Schmidt, Göttingen 1948; H. Kliewe, Leitfaden der Entseuchung und Entwesung, F. Enke Verlag, Stuttgart 1951. |

| [10] | Patent No. 438818 (D 41941 IV/451, Dec. 27, 1926), kindly provided by C. Mattogno. According to this, the preparation released practically all hydrogen cyanide within 10 minutes. |

| [11] | Jahresbericht VIII der Chemisch-Technischen Reichsanstalt, Verlag Chemie, Berlin 1930, pp. 77f. |

| [12] | R. Irmscher, “Nochmals: “Die Einsatzfähigkeit der Blausäure bei tiefen Temperaturen”,” Zeitschrift für hygienische Zoologie und Schädlingsbekämpfung, 1942, Vol. 34, p. 36. |

| [13] | F.I.A.T. Final report, Fumigants distributed by DEGESCH, A.G., Weissfrauenstrasse 9, Frankfurt, British Intelligence Objectives Sub-Committee, Her Majesty Stationery Office, London Oct. 1, 1945, p. 1. |

| [14] | B.I.O.S. Final report, The storage of grain in Germany with special reference to the control of insect pests, British Intelligence Objectives Sub-Committee, Her Majesty Stationery Office, London, Oct.-Nov. 1945, p. 30. |

| [15] | See illustrations in J.-C. Pressac, op. cit. (note 6) p. 17, from DEGESCH product information (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Schädlingsbekämpfung); see also G. Peters, Blausäure zur Schädlingsbekämpfung, op. cit. (noite 8), S. 80; Anzeiger für Schädlingskunde, Vol. 13 (1937), p. 36; while the discoid version was identified as such on the label, it is not clear from these illustrations whether the Erco and Diagrieß versions were also identified as such. With regard to a Zyklon-B can from the Kolin, see J. Borkin, The Crime and Punishment of I.G. Farben, The Free Press, New York 1978, p. 114. |

| [16] | A. Moog, W. Kapp, Letter from Detia Freyberg GmbH to G. Rudolf, Laudenbach, Sept. 9, 1991. According to the gentlemen of Detia Freyberg, this company continues the business of DEGESCH, which became American property after the war. On the mass portion of the carrier relative to the total mass: phone conversation between G. Rudolf and W. Kapp on January 10, 1992. Unfortunately, all the physical information provided by the manufacturers on the product Zyklon B/Cyanosil is strangely vague. The portion of hydrogen cyanide relative to the total mass of the product can be taken from DEGESCH’s calculations, cf. note 5. |

| [17] | G. Peters, Blausäure zur Schädlingsbekämpfung, op. cit. (note 8), pp. 64f. |

| [18] | Letter from ARED GmbH to G. Rudolf, Linz, refz. 1991-12-30/ Mag.AS-hj. |

| [19] | If the temperature is lowered from the boiling point of hydrogen cyanide to 0°C, the evaporation time would roughly triple. However, the evaporation of hydrogen cyanide from the carrier even at freezing temperatures is delayed less by adsorption effects than would be expected for free hydrogen cyanide, cf. G. Peters, W. Rasch, “Die Einsatzfähigkeit der Blausäure-Durchgasung bei tiefen Temperaturen,” Zeitschrift für hygienische Zoologie und Schädlingsbekämpfung, 1941, Vol. 33, pp. 133f. |

| [20] | See War Department, Hydrocyanic-Acid-Gas Mask, US Government Printing Office, Washington 1932; War Department, Technical Manual No. 3-205, US Government Printing Office, Washington 1941; Hauptverband der gewerblichen Berufsgenossenschaften, Atemschutz-Merkblatt, Carl Heymanns Verlag, Cologne, Oct. 1981; R. Queisner, “Erfahrungen mit Filtereinsätzen und Gasmasken für hochgiftige Gase zur Schädlingsbekämpfung,” Zeitschrift für hygienische Zoologie und Schädlingsbekämpfung, 1943, Vol. 35, pp. 190-194; DIN 3181, Part 1, draft, Atemfilter für Atemschutzgeräte. Gas- und Kombinationsfilter der Gasfilter-Typen A,B,E und K. Sicherheitstechnische Anforderungen, Prüfung, Kennzeichnung, Beuth Verlag GmbH, Berlin, May 1987. |

| [21] | Now in The Chemistry of Auschwitz, Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield, 2017, Chapter 7.3.1.3.2. “HCN Quantities Deduced from Execution Times,” pp. 250-267; the most-recent edition is posted at https://holocausthandbooks.com/book/the-chemistry-of-auschwitz/. |

| [22] | So e.g. J. Borkin, op. cit. (note 15); K. Naumann, op. cit. (note 2), by the way, reports the use of Zyklon B without an irritant in 1924. |

| [23] | The first date for such a resolution is given today as August 31, 1941 at the earliest, cf. Y. Bauer, Freikauf von Juden?, Jüdischer Verlag, Frankfurt/Main 1996, p. 98. |

| [24] | The dating of the alleged first experimental gassing with Zyklon B in Auschwitz is very contradictory and varies between September 1941 and spring 1942, cf. C. Mattogno, Auschwitz: The First Gassing, 3rd ed., Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield, 2016; J.-C. Pressac, Die Krematorien von Auschwitz. Die Technik des Massenmordes, Piper, Munich 1994. |

| [25] | “Runderlaß des Reichsministers für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft,” 3 April 1941, II A3 – 143, in: Zeitschrift für hygienische Zoologie und Schädlingsbekämpfung, Vol. 33 (1941), p. 126. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 10(2) (2018); first published as “Zyklon B – eine Ergänzung” under the pen name Wolfgang Lambrecht in Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung, Vol. 1, No. 1 (1997), pp. 2-5

Other contributors to this document:

Editor’s comments: