Franciszek Ząbecki: Neither Stationmaster nor Photographer of Treblinka

Franciszek Ząbecki was a Polish railway worker during the Second World War at the Treblinka train station a few kilometers north of the two Treblinka camps. A number of myths have grown up around him, including that he was stationmaster during the war, that he took a photograph during the prisoner uprising at the Treblinka “death camp,” and that the photo he took is unique. Based mainly on documents written by Ząbecki himself, all of these assertions are shown to be inaccurate narratives that modern Holocaust historians consistently repeat. In addition, an additional photograph of the “burning of Treblinka” that has been recently rediscovered by CODOH is presented and analyzed.

Franciszek Ząbecki was the stationmaster of Treblinka train station, and took a unique, iconic photograph of the Treblinka II camp on fire during the Jewish inmate uprising of August 2, 1943. These are two of the most important aspects of traditional accounts of Ząbecki during World War II. Numerous historians attest to either or both of these facts. However, none of this is accurate, and requires serious revision. The main sources for overturning these myths are the words of Ząbecki himself.

Recent Mentions of Ząbecki in Mainstream Works

Below are a few recent examples from mainstream Holocaust literature specifically on the Treblinka Camp. We have chosen these works, since they illustrate how the incorrect assumptions about Franciszek Ząbecki are not even evaluated by these historians, let alone corrected, before being repeated. They are simply taken at face value.

The latest is from a 2024 book by Jacob Flaws, Spaces of Treblinka:

“Franciszek Ząbecki, the Polish stationmaster at Treblinka (4 km), remembered […]” (p. 53)

“Photo taken by local railway man Franciszek Ząbecki. The smoke comes from Treblinka during the revolt on August 2, 1943.” (p. 143, image caption)

Chris Webb of DeathCamps.org, Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team (H.E.A.R.T.), and the Holocaust Historical Society co-authored a book with Michal Chocholatý, The Treblinka Death Camp. The latest published version is from 2021, with a new edition forthcoming in 2026:

“Franciszek Ząbecki was the Polish stationmaster at Treblinka village station, and a member of the Polish Underground.” (p. 19)

“Franciszek Ząbecki, the station-master at Treblinka […].” (p. 34)

“Franciszek Ząbecki, the station-master, has stated […].” (p. 61)

“Franciszek Ząbecki, the station-master at Treblinka, recalled […].” (p. 64)

“Franciszek Ząbecki, the station-master at Treblinka, witnessed […].” (p. 128)

“Franciszek Ząbecki, the Polish station-master at Treblinka who claims […].” (p. 221)

Webb’s DeathCamps.org has a page last updated December 28, 2005, titled “The Treblinka Station Master Franciszek Zabecki.” The Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team’s website has a page with a copyright date of 2007 titled “Franciszek Zabecki – The Station Master at Treblinka: Eyewitness to the Revolt – 2 August 1943.” Finally, the Holocaust Historical Society website has a page dated June 7, 2022 titled “Zabecki Station Master at Treblinka.”

The Treblinka Museum published an exhibit catalog in 2021 titled “Stacja Treblinka Między życiem i śmiercią” (“Treblinka Station: Between Life and Death”). Monika Samuel is listed as the exhibition curator, with Dr. Edward Kopówka as supervisor. Much of the catalog examines the experiences of Franciszek Ząbecki at the Treblinka train station:[1]

“Franciszek Ząbecki is also the author of a unique photograph of the Treblinka II extermination camp. On August 2, 1943, he photographed the smoke rising above the camp, which had been set on fire by prisoners during an uprising. This is the most famous photograph of this death camp.”

“Photograph by Franciszek Ząbecki showing the burning Treblinka II extermination camp after the prisoners’ revolt on August 2, 1943.”[2]

In Treblinka Warns and Reminds, a 2022 book published by the Treblinka Museum and translated into English in 2024, Monika Samuel contributes an article titled “Railwayman Franciszek Ząbecki. Memoirs of a Witness from Treblinka.” This article utilizes much of the research from the 2021 exhibit catalog:[3]

“Franciszek Ząbecki is also the author of a unique photo of the Treblinka II Extermination Camp. On August 2, 1943, he photographed the smoke over the camp set on fire by prisoners during the revolt.”

“Photograph by Franciszek Ząbecki depicting the burning Treblinka II Extermination Camp after the prisoners’ revolt on August 2, 1943.”[4]

Michal Wojcik’s account of the Treblinka uprising, Treblinka 43: Bunt w fabryce smierci (Treblinka 43: Revolt at the Death Factory), also attributes the photo to Ząbecki. Somehow, Wojcik even knows the conditions under which it was taken:[5]

“The photo was taken secretly by Franciszek Ząbecki, an employee of the Polish railway at the Treblinka station.”

The Holocaust Controversies blog, in their white paper Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: Holocaust Denial and Operation Reinhard, refers to Ząbecki once in a footnote:[6]

“The naming of ‘Treblinka’ might be ascribed to a postwar confusion by the witness, were it not for the fact that Francizek Zabecki, the Treblinka stationmaster […].”

Online sources also repeat these assertions. The National WWII Museum has an online article on “The Treblinka Uprising,” written by the same Jacob Flaws cited above. The iconic photograph is the first image people see when visiting the page:[7]

“Photo of Treblinka uprising from a distance by Polish train station worker Franciszek Ząbecki.”

Even the Jewish Historical Institute, which has the photo in its own collection, credits it to Franciszek Ząbecki, in the only article on their website that mentions Ząbecki in any capacity:[8]

“Treblinka burning during the uprising. Photo taken by Polish railwayman Franciszek Ząbecki. Collection of the Jewish Historical Institute.”

All of these assertions are false and contradicted by Ząbecki himself in numerous places over multiple decades: his 1944 Soviet interrogation, his 1945 Polish interview, in a pair of signed statements he gave to Miriam Novitch in 1965, and in his 1977 memoirs titled Wspomnienia dawne i nowe (Memories, Old and New).

In fact, Ząbecki was not the stationmaster of Treblinka during the war, he did not take the famous photograph, and the photo is not “unique.” Recently, CODOH has rediscovered a second photograph taken at the same place mere moments after the more well-known photo, hidden in plain sight for nearly five decades.

The Unique Photograph Revised

The below is the famous photograph that is widely asserted to be the Treblinka II camp on fire during the inmate uprising. Since it was donated by Ząbecki to Miriam Novitch of the Ghetto Fighters House museum in Israel, we refer to it as the “Donation photo.”

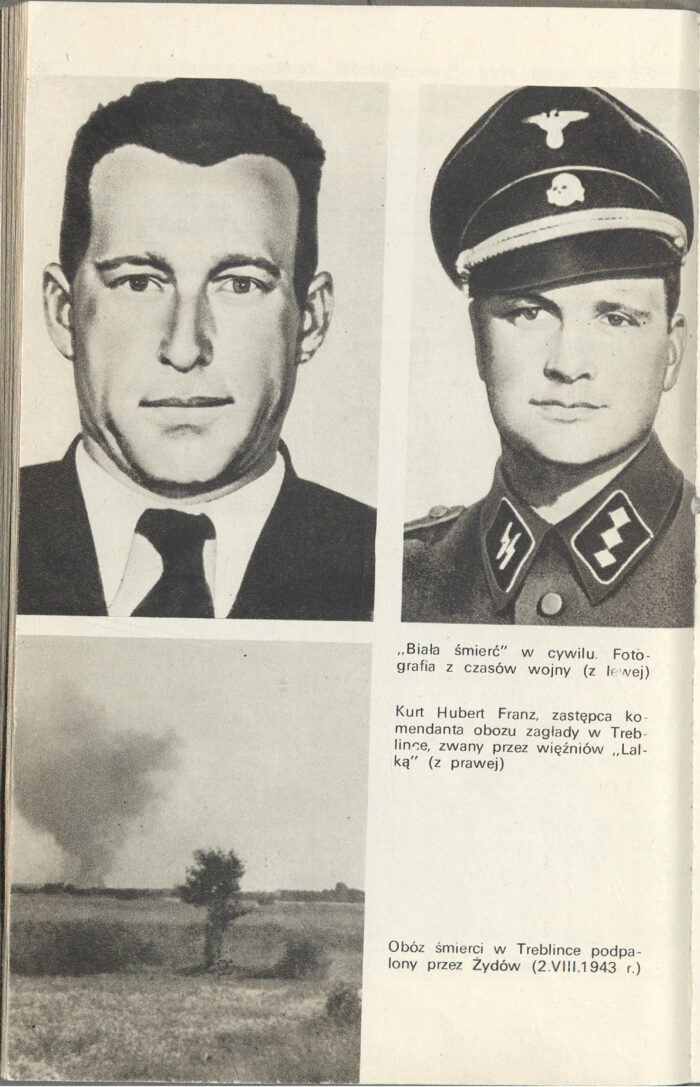

Below, we reproduce the full image-insert page containing a second photograph of this scene that appears in Ząbecki’s 1977 memoirs. We refer to this as the “Memoirs photo.”

While similar, these are different photographs. The Donation photo was taken seconds to a couple minutes before the Memoirs photo. There are numerous differences between the two that cannot be accounted for by printing defects:

- The Memoirs photo has a higher smoke plume, indicating it was taken slightly after the original as the smoke expanded and ascended due to wind and convection of warm air upwards.

- The Memoirs photo is angled slightly further to the right, showing details of the treeline and landscape that are not visible in the Donation photo.

- There are slight differences in the shape of the branches on the tree in the foreground, indicating wind movement between shots.

- The photos have different defects in terms of black dots, a scratch, blurring, and general noise.

Below, the two photos are shown side-by-side. It is likely that the Memoirs photo has been cropped from an original that shows the same extended scene as the well-known version.

Finally, a colorized version of each cropped to the area of interest highlights the differences between the two.

It should be evident that these are not different scans of the same photograph, and we have rediscovered this image that is virtually unknown to mainstream historians and the Treblinka Museum, who claim the Donation photo is “unique.”

It should be evident that these are not different scans of the same photograph, and we have rediscovered this image that is virtually unknown to mainstream historians and the Treblinka Museum, who claim the Donation photo is “unique.”

More information is posted on the CODOH Wiki, including both images in the highest-resolution raw format we could find, an overlay showing the extension of the treeline in the background of the Memoirs photo, and discussion of finer details like differences in the tree branches likely caused by shifting winds in between shots.[9]

We now move on to the myth that Ząbecki was the stationmaster of Treblinka train station, before discussing who actually took these photographs.

Not the Stationmaster

Franciszek Ząbecki became the stationmaster at Treblinka, but not until September 1944, after the Germans had fully retreated and the Soviet Red Army captured the area. The Soviets began their first investigation of the Treblinka camps in August 1944, and Ząbecki was interrogated by them the following month.

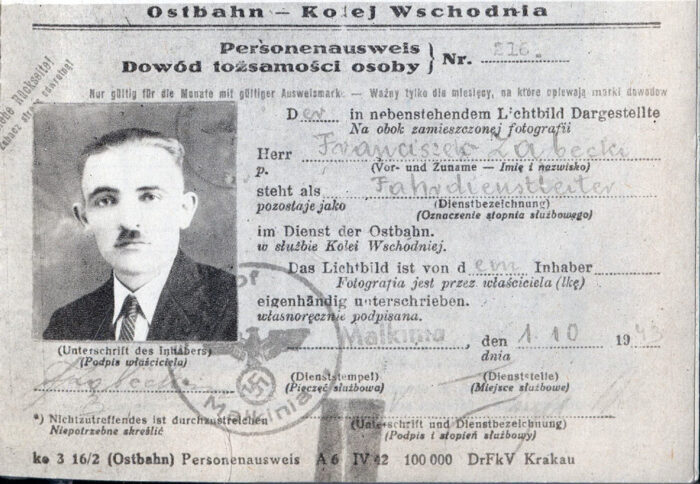

During the war years, Ząbecki was a dispatcher at the station, in addition to being a member of the Polish Armia Krajowa (Home Army) (code names “Dawny,” “Józuba”). The occupation listed on his Ostbahn ID card is “Fahrdienstleiter,” which translates to “dispatcher.”[10] In an interview in 1945 in Polish, he referred to his wartime position as a “dyżurny ruchu,” which translates to “traffic/transport dispatcher/controller.”[11]

In addition to having a stamp inconsistent with many other German stamps of the time, the card was issued on October 1, 1943, after the Treblinka uprising. If authentic, this may have been the final ID card issued to Ząbecki by the Germans, and it confirms he was not the stationmaster while the Treblinka Camp was in operation.

Ząbecki himself also states that he was never the dispatcher of the Treblinka station during the war. When offered the position, he turned it down because the duties of the job would conflict with his activities in the Polish Home Army:[12]

“After Pronicki’s departure, ‘Zagonczyk’ offered me the position of stationmaster. He also asked if it suited me and if it would not conflict with my underground work. After considering the matter, we concluded that I would gain nothing from it: nothing morally, little materially, and I would have less time for ‘my own affairs.’ […]

I missed out on promotion. I didn’t become a stationmaster.

Józef Kuźmiński took Pronicki’s place as stationmaster.”

“Zagonczyk” was the code name for Robert Dąbrowski, the stationmaster in Sokołów Podlaski. Józef Pronicki and Józef Kuźmiński were the two stationmasters during the war. Pronicki served as stationmaster until February or May 1943, and was also a member of the Polish Underground.[13]

The information that Ząbecki was not the stationmaster is not new information. From his first interrogation with the Soviets on September 24, 1944, he named Pronicki and Kuźmiński as the stationmasters.[14]

Not a Famous Photographer

Referring to Ząbecki as a stationmaster is inaccurate, although an anachronistic mistake. After all, he eventually attained that role under Soviet occupation. For the historians listed above, this is an error, but an understandable one.

Less understandable is attributing the famous “Burning of the Treblinka Death Camp” photograph to Ząbecki when he clearly stated he never took it from the moment the first version appeared in 1965. This is the Donation photo shown earlier.

In his memoirs, Ząbecki writes that he initially showed the photograph to the judge and attorneys in January 1965 at the trial of Kurt Franz, deputy commandant of the Treblinka II camp, and others in Düsseldorf, Germany:[15]

“I added that I had a photo of the burning camp from a distance. I thought this would pique the Court’s interest and compel them to hear further testimony. Yes, the Court viewed the photos, as did the defense attorneys and prosecutors, but they weren’t interested in any other facts. While viewing the photo, the prosecutor asked me a question:

‘Did the witness work at the station himself?’

‘No!’ I replied. ‘My friend and I worked in shifts; he helped me register arriving trains; this friend was also a member of the underground.’”

Ząbecki worked at the station, so “the witness” refers to the person who took the photograph. According to Ząbecki, this unidentified person did not work at the station himself.

After testifying, Ząbecki relates the story of meeting Miriam Novitch, a founder of the Ghetto Fighters House museum in Israel:[16]

“When I and the German Red Cross representative went out to the waiting room, a woman approached me, introducing herself as a correspondent from Israel, adding in Polish that she was born in Warsaw and named Miriam Novitch. She thanked me for my testimony and asked me to give her a photo of the burning camp to the Tel Aviv museum, and in return, she would give me a photo of a model of the Treblinka camp, taken by Jakub Wiernik, who had worked in a labor group at the death camp and escaped during the uprising. I gladly exchanged the photo, as it had been made in several prints. She then invited me to a conversation in the café of the Hotel Germania to provide a more detailed account of the Treblinka tragedy.”

In the Ghetto Fighters House Archives are documents from Ząbecki’s meeting with Novitch that clear up the mystery of who took the photo. Ząbecki handwrote and signed a statement, and signed a typed version of the same statement on letterhead from the Hotel Germania, dated January 19, 1965. He identifies a “Zygmunt Wierzbowski” as the person who took the photo:[17]

“I, the undersigned, Franciszek Zabeki, born on 8 October 1907, residing in Piastow (Warsaw), ul. 22 LIPCA 16/1, confirm that the photograph which I handed to Ms. Miriam Novitch on 19 January 1965 in Düsseldorf, in the court building, where I was questioned as a witness, comes from Mr. Zygmunt Wierzbowski and was taken by him on 2 August 1943: I present: The burning of the Treblinka II Death Camp.

This is original. I confirm that in the years 1941-1945, I was on duty at the Treblinka Station.

Donates Photographs to the Ghetto Uprising Museum in Israel.”

Ząbecki’s signatures on both documents are consistent with that of his 1943 Ostbahn ID card, and Miriam Novitch is listed on the archive’s website as the donor of these signed statements. Notably, the document uses the term “fotografie,” which is a plural version of the singular “fotografia” for “photograph.” It is not clear if he turned over multiple shots, or several copies of the same shot, or turned over only the single photo. Only the Ghetto Fighters House archive would be able to confirm this.

Ząbecki’s memoirs are not considered entirely reliable, due to degraded memories, an attempt to boost the profile of himself and other Poles’ wartime conduct in relation to the Jews, or communist censorship at the time. For instance, Ząbecki claims to have met Jankiel Wiernik on two occasions when conducting surveillance on the camp, while Ząbecki was attempting to inspire a Jewish rebellion in the camp on the suggestion of the Home Army. Historians do not take this account seriously, despite Ząbecki relating it in his memoirs and in a short 1967 typescript titled “Plan of the Treblinka Extermination Camp: Execution.”[18]

Who Was Zygmunt Wierzbowski?

There are at least two possible identities for Zygmunt Wierzbowski. In his memoirs, Ząbecki only mentions him once as a “supervisory dispatcher” at Treblinka station around July 1944.[19] He is mentioned nowhere else in the book. Notably, Ząbecki does not reveal Wierzbowski’s Home Army code name, whereas he constantly references the code names of fellow members of the Polish Underground throughout his memoirs. In many cases, he only refers to people by their code name.

In 1945, Judge Zdzisław Łukaszkiewicz interviewed Ząbecki and several other Polish railroad workers: Józef Kuźmiński, Wacław Wołosz, Mieczysław Lasowski, Stanysław Adamczyk, Lucjan Puchała, Wacław Bednarczyk, Stanysław Borowy, and Władysław Chomka.[20] Neither former stationmaster Józef Pronicki nor supervisory dispatcher Zygmunt Wierzbowski were among those interviewed. None of the interviewees mention Wierzbowski in their interviews, although many of them mention no people by name.[21]

While the Polish Centralnego Archiwum Wojskowego (Central Military Archive) lists no one with the name Zygmunt Wierzbowski, there was one Home Army member with that name, an electrical engineer who lived in, and was the leader of, a group in Warsaw (code names “Konary”, “Nenufar”). This Wierzbowski worked as technical director at a power plant in Warsaw during the war, and oversaw the sabotaging of the plant. For example, in March 1943, the entire plant was immobilized due to a serious act of sabotage by the group.[22] In short, this Wierzbowski’s Home Army formation has no known presence near Treblinka on the date of the revolt, so it is difficult to place him in the area on the relevant day to have had the opportunity to take the photos.[23]

Consulting telephone directories from the 1930s and 1940s, the only Zygmunt Wierzbowski listed in the Warsaw District is the aforementioned electrical engineer. Thus, if Wierzbowski, the electrical engineer, took the photo, it wasn’t taken of Treblinka on August 2, 1943. If a different Zygmunt Wierzbowski took the photo of Treblinka on August 2, 1943, then this person’s concrete link to Treblinka is currently not established.[24]

Regardless of who “supervisory dispatcher” Zygmunt Wierzbowski was, the largest issue with the photos is that they did not appear until 1965, so could have been taken at any time or place before then. Because Ząbecki said someone else took the Donation photo, he is unable to authenticate the document. Ząbecki is said to have turned over numerous railway traffic documents to Judge Łukaszkiewicz in the course of the 1945 investigation of Treblinka by the Main Commission for the Investigation of German Crimes in Poland, but this photo is not mentioned or included.[25] He also never brought up the photo during his 1944 Soviet interrogation that contains unique atrocity propaganda and exaggerations which he immediately abandoned. During that interrogation, he did not mention saving any documents at all. In lieu of mentioning documents and photographs that he had in his possession, Ząbecki reported:[26]

“The Germans and guards who guarded the prisoners were always drunk. I know that they forced people to eat vomit, i.e., what they threw up on the ground while drunk, forcing the prisoners to lick up the puke on the ground.”

Franciszek Ząbecki: A Case of “Perfect Revisionism”

In 2013, Jett Rucker wrote an article for Inconvenient History, outlining his concept of “perfect revisionism.” He laid out these criteria:[27]

“(a) it demolishes predominant historical opinion; (b) it is entirely based on information previously known, but not previously considered in the investigations; and (c) the findings themselves are immune to any suspicion of any revisionist agenda beyond that of the [document’s] authenticity, […].”

In the case of Franciszek Ząbecki, we have three instances of “perfect revisionism.” The historical accounts that he was stationmaster, took a photo, and that the photo is unique are all false, although they are the predominant opinion subscribed to by numerous authors who have published works on the Treblinka Camp, including the Treblinka Museum. Furthermore, the revisions discussed in this paper are based on information previously known but not previously considered: Ząbecki’s testimony, archival documents from Jewish institutes containing his signature and his own memoirs. Finally, they should be immune to any suspicion of a “revisionist agenda,” whatever that means, as they rely solely on the authenticity of the documents cited.

In addition to the documents Ząbecki is alleged to have collected from Treblinka station before it was blown up by the Germans, he is most often referred to when mentioning his position as stationmaster and his taking of the “unique” photo of the burning camp during the uprising. The myths we have explored here show up repeatedly in mainstream print and online literature on Treblinka.

The Treblinka Museum is in the best position to correct their own misattribution of the photo to Ząbecki. In the Museum’s exhibit catalog and related studies on Ząbecki, they included the well-known photo with a caption referencing Ząbecki’s memoirs, which we have shown includes a separate and distinct photo of the same scene. Perhaps they did not notice that the photo in Ząbecki’s book was different, and simply grabbed the only version available online, the Donation photo. In addition, the museum has the easiest access to Polish archives to determine who the Zygmunt Wierzbowski was whom Ząbecki referred to when donating the photo, whether there is evidence Wierzbowski was employed at Treblinka or any train station in the area during the war, whether he was in the Home Army, and if so, then what his code name was.

Possibly the most egregious blunder on these issues has been committed repeatedly by Chris Webb over two decades. His websites invariably identify Ząbecki as the stationmaster, and include an excerpt from Ząbecki’s memoirs on the Treblinka uprising. He cites the memoirs directly, not a secondary source that quotes an excerpt of them, so it has to be assumed that he referred to the actual book. Thus, it is inexplicable that he missed Ząbecki’s dozens of references to the actual stationmasters by name, even if he missed the part where Ząbecki explicitly turned down the promotion to stationmaster.

Compounding the error, Webb and Chocholatý’s book The Treblinka Death Camp bolsters the credibility of Ząbecki by referring to his position:[28]

“Franciszek Zabecki was the Polish stationmaster at Treblinka village station, and a member of the Polish Underground. He had been placed at Treblinka by the AK (Armia Krajowa-Home Army), the biggest Polish Underground movement, originally to report on the movement of German troops and equipment. He was therefore the only trained observer on the spot throughout the entire existence of the Treblinka extermination camp.”

It would be difficult to make more mistakes of fact and interpretation in a single paragraph. Ząbecki was not the stationmaster, and not the only person in the AK at the station. He was not “therefore the only trained observer,” and he specifically turned down the role of stationmaster, because it would have interfered with his Home-Army and surveillance activities.

Ząbecki’s memoir is referenced in the bibliography sections of Flaws’s book, Webb and Chocholatý’s book, Webb’s websites and Samuel’s exhibit catalog and book chapter. It should be taken for granted that they read the memoirs, even though it is in Polish with no official English translation. If so, it is inconceivable that they missed such aspects of the book as the images or Ząbecki’s repeated references to the actual stationmasters.

From the moment Ząbecki showed up in the historical record in the 1944 and 1945 Soviet-Polish investigations, it was established that he was not the stationmaster of Treblinka. The signed statements from the Ghetto Fighters House have existed since 1965, drafted the same day the photograph first appeared. His memoirs were published in 1977 and reinforce these points. Even though a second photograph is contained in his book, the caption does not attribute it to him, and his recounting of his 1965 testimony makes it clear that he did not take the photos.[29]

This discarding of nearly everything a witness has said or written is referred to as “convergence of evidence,” and it results in the spread of misconceptions, mistakes, lack of context, and not carefully examining a book that a historian cites. It displays a lack of respect for Ząbecki when historians disregard his own words, while utilizing myths about him that appear convenient in reinforcing a preferred narrative of the Treblinka camps and surrounding area. It has been over 80 years since Ząbecki told the Soviets that Pronicki and Kuźmiński were the stationmasters, and 60 years since he told Miriam Novitch that someone else took the famous photograph. It has been nearly 50 years since a different photograph of the same scene was printed in his memoirs.

These misconceptions have had a few implications. First, stationmaster Józef Pronicki has essentially been written out of the history of Treblinka station. In his 1945 interview, stationmaster Józef Kuźmiński reports almost nothing about the “death camp,” reporting witnessing only “a dozen or so transports of Jews.”[30] If the stationmaster was “the only trained observer,” to use Webb’s phrase, then further research on what Pronicki wrote or said, if anything, is warranted, since he was the actual stationmaster during more of the time period of the camp’s existence.

Second, an unauthenticated photograph taken by an unknown person has been attributed to Franciszek Ząbecki, despite Ząbecki’s statements to the contrary. This obfuscates the additional problem that the photo was unknown to virtually anyone before January 1965, and so far no research has been done to determine whether Ząbecki’s “friend” Zygmunt Wierzbowski existed, who he was, when and where he took the photos (if he took them to begin with), or the circumstances under which Ząbecki acquired them.

Third, by relying on secondary sources, and by erroneously assuming that the famous photograph was reprinted in Ząbecki’s memoirs, the inaccurate claim that the photo of the burning Treblinka Camp was “unique” was reinforced. In fact, if Ząbecki had at least two photographs of this event in his possession, what is to say that more photos were not taken and are currently awaiting discovery? They may be in the possession of Ząbecki or Wierzbowski family members, or have been donated to an archive, or are simply lost by now.

Finally, mainstream historians are seemingly unable to correct these misconceptions about Ząbecki. As illustrated above, these myths have been spread for decades, and continue to be spread in publications from as recent as 2024. Instead of being cleared up, the mistakes are turning into “official” history, as historians spread each other’s secondary sources without looking at primary documents with their own eyes. Such a level of trust may be admirable, but has resulted in inaccurate assumptions ossifying into accepted “truths.” What else is awaiting reevaluation by looking at primary source documents instead of copying secondary references and passing them off as primary-source research?

The focus on Ząbecki’s documents, his alleged position as stationmaster, and the assumed “unique” nature of the photograph results in a myopic view of the man and his written accounts of his wartime experiences. Despite the unreliability of Ząbecki’s testimony and memoirs in certain aspects, he made a number of highly relevant observations regarding the heavy and important railway traffic through the Małkinia-Siedlce railway line. Many of these observations could help us understand activity throughout this region that was critical to the war, as Ząbecki describes numerous types of civilian and military traffic through the area via rail, road and foot.

Smoke over Treblinka – Editor’s Remarks

When I read the above article on its submission, I was puzzled. Why would anyone in the summer of 1943 have bothered taking a picture of smoke rising over Treblinka? Doesn’t the orthodoxy claim that gigantic fires were constantly burning in the alleged Treblinka Extermination Camp since the spring of 1943, right up to the famous inmate uprising? If that was so, the skies around that camp would have been covered in smoke continously and uninterruptedly for months by the time the inmates set some camp facilities on fire during their uprising, causing some more smoke. It would not have been an unusual sight for anyone in the area. It would have been no particular reason to fetch a camera and make photos, anyhow. Or was it?

To figure this out, I asked Google AI on Dec. 29, 2025:

“How many metric tons of wood were contained in a standard German ho[r]se-stable barracks of World War Two?”

The answer:[31]

“A standard German horse-stable barracks of World War II—specifically the Pferdestallbaracke Type OKH 260/9, which was widely used in concentration camps and by the military—contained approximately 30 to 40 metric tons of [dry] wood. […]

While designed for 52 horses, the SS adapted these barracks in camps like Auschwitz-Birkenau to house between 400 and 700 prisoners, and in extreme cases, upwards of 1,000 people.”

Where am I getting with this?

During the claimed “cremation period” of the Treblinka II Camp, at least some 700,000 bodies are said to have been cremated on open-air fires using wood as fuel. The period of time in which this is said to have happened lasted some 122 days. Dry wood required to burn a body on such a fire is at least 5 times the body mass.[32] Assuming a body mass of only some 35 kg on average, this results in 175 kg of dry wood per body, or some 122,000 metric tons of wood. If that wood was fresh, the amount required roughly doubles. This means that, on average, some 1,000 metric tons of dry wood were burned daily, in addition to the roughly (700,000 × 0,035 t ÷ 122 days =) 200 metric tons of human bodies.

That daily conflagration would have amounted to the burning of (1000 t ÷ 35 t =) 29 horse-stable barracks. If the wood was fresh, this number roughly doubles.

The Treblinka II Camp is said to have had only a few buildings, but most certainly not some 30 or even 60 large inmate buildings capable of housing some 12,000 to 60,000 inmates.

In other words, what is said to have transpired in the spring and early summer of 1943 would have resulted in smoke that would have been at least ten times more intense than the burning of a few buildings during the inmate uprising of August 2, 1943. In fact, since only fresh wood would have been available from the surrounding forests, which would have necessitated not only twice the amount of wood, but moreover would have caused extreme volumes of smoke (wet wood smokes much more than dry wood), the smoke resulting from the open-air cremation of more than 700,000 inmates would have dwarfed the smoke from the inmate uprising easily by more than an order of magnitude in smoke quantity, and by two orders of magnitude regarding the time span during which that smoke is said to have darkened the sky around Treblinka.

Evidently, the smoke caused by the inmate uprising was so unique that it caused someone to make a few photos of it. Yet the 122 days of continuous smoking of at least ten times that intensity evidently didn’t trigger anyone to ever take notice, let alone take a photo of it.

Zabecki himself stated that the smoke caused by the inmate uprising was different from the “everyday martyrdom-like smoke,” meaning the smoke that rose during the camp’s “normal” operations, whatever these were. He describes it like this in his memoirs:

“On a hot day, Monday, August 2, 1943, at 3:45 PM, we saw from the Treblinka station great clouds of smoke, interspersed with flames from the fire rising above the camp. This was a different smoke, not the everyday martyrdom-like smoke.” (Page 94)

Had the “everyday martyrdom-like smoke” vastly exceeded the smoke caused by the uprising, the uprising would not even have been noticed by anyone outside the camp by its smoke, as it would have aded only a few percent more smoke to usual daily smoke. This suggest that what Zabecki calls the “everyday martyrdom-like smoke” must have been vastly smaller, making it even less worth taking a few photos of.

Occam’s Razor suggests the following, simplest explanation for the lack of any photo of that claimed 122-day-lasting open-air conflagration of 700,000 murdered inmates: it never happened.

Bibliography

1945 Court Testimony of Polish Railway Workers

- Adamczyk, Stanisław. “Stanisław Adamczyk, Testimony from Court/Criminal Proceedings from 26.10.1945.” Interview by Zdzisław Łukaszkiewicz. October 26, 1945. Archive of the Pilecki Institute, Chronicles of Terror (Institute of National Remembrance, GK 196/69). https://chroniclesofterror.pl/dlibra/show-content?id=252.

- Bednarczyk, Wacław. “Wacław Bednarczyk, Testimony from Court/Criminal Proceedings from 27.10.1945.” Interview by Zdzisław Łukaszkiewicz. October 27, 1945. Archive of the Pilecki Institute, Chronicles of Terror (Institute of National Remembrance, GK 196/70). https://chroniclesofterror.pl/dlibra/show-content?id=242.

- Borowy, Stanisław. “Stanisław Borowy, Testimony from Court/Criminal Proceedings from 21.11.1945.” Interview by Zdzisław Łukaszkiewicz. November 21, 1945. Archive of the Pilecki Institute, Chronicles of Terror (Institute of National Remembrance, GK 196/69). https://chroniclesofterror.pl/dlibra/show-content?id=257.

- Chomka, Władysław. “Władysław Chomka, Testimony from Court/Criminal Proceedings from 16.11.1945.” Interview by Zdzisław Łukaszkiewicz. November 16, 1945. Archive of the Pilecki Institute, Chronicles of Terror (Institute of National Remembrance, GK 196/69). https://chroniclesofterror.pl/dlibra/show-content?id=262.

- Kuźmiński, Józef. “Józef Kuźmiński, Testimony from Court/Criminal Proceedings from 16.10.1945.” Interview by Zdzisław Łukaszkiewicz. October 16, 1945. Archive of the Pilecki Institute, Chronicles of Terror (Institute of National Remembrance, GK 196/69). https://chroniclesofterror.pl/dlibra/show-content?id=280.

- Lasowski, Mieczysław. “Mieczysław Lasowski. Testimony from court/criminal proceedings from 21.12.1945.” Interview by Zdzisław Łukaszkiewicz. December 21, 1945. Arolsen Archives (1.2.7.7/82185969 – 82185970/ITS Digital Archive). https://collections.arolsen-archives.org/en/archive/1-2-7-7_9038700.

- Puchała, Lucjan. “Lucjan Puchała, Testimony from Court/Criminal Proceedings from 26.10.1945.” Interview by Zdzisław Łukaszkiewicz. October 26, 1945. Archive of the Pilecki Institute, Chronicles of Terror (Institute of National Remembrance, GK 196/69). https://chroniclesofterror.pl/dlibra/show-content?id=248.

- Wołosz, Wacław. “Wacław Wołosz, Testimony from Court/Criminal Proceedings from 18.10.1945.” Interview by Zdzisław Łukaszkiewicz. October 18, 1945. Archive of the Pilecki Institute, Chronicles of Terror (Institute of National Remembrance, GK 196/69). https://chroniclesofterror.pl/dlibra/show-content?id=308.

- Ząbecki, Franciszek. “Franciszek Ząbecki, Testimony from Court/Criminal Proceedings from 21.12.1945.” Interview by Zdzisław Łukaszkiewicz. December 21, 1945. Archive of the Pilecki Institute, Chronicles of Terror (Institute of National Remembrance, GK 196/70). https://chroniclesofterror.pl/dlibra/show-content?id=310.

Phonebooks

- List of Active Telephones of the Warsaw Network 1940. Biuro Nowoczesnej Reklamy, 1940. Originally published as Wykaz Czynnych Telefonów Warszawskiej Sieci 1940. https://mbc.cyfrowemazowsze.pl/dlibra/publication/10871/edition/9821/.

- List of Subscribers of the Warsaw Telephone Network of the Polish Joint-Stock Telephone Company, 1930-1931. E. and K. KOZIAŃSKI GRAPHIC ARTISTS’ STUDY IN WARSAW, 1931. Originally published as Spis Abonentów Warszawskiej Sieci Telefonów Polskiej Akcyjnej Spółki Telefonicznej 1930-31. https://mbc.cyfrowemazowsze.pl/dlibra/publication/edition/9886/.

- List of Subscribers of the Warsaw Telephone Network of the Polish Joint-Stock Telephone Company, 1935-1936. ZAKŁ. GRAF. „NOWOCZESNA SPÓŁKA WYDAWNICZA” S. A. MARSZAŁKOWSKA 3-5-7, 1935. Originally published as SPIS ABONENTÓW WARSZAWSKIEJ SIECI. https://mbc.cyfrowemazowsze.pl/dlibra/publication/edition/9883/.

- List of Subscribers of the Warsaw Telephone Network of the Polish Joint-Stock Telephone Company, 1937-1938. GRAPHIC PRINTING STUDIO “DOM PRASY” S. A. MARSZAŁKOWSKA 3-5-7, 1937. Originally published as SPIS ABONENTÓW WARSZAWSKIEJ SIECI TELEFONÓW POLSKIEJ AKCYJNEJ SPÓŁKI TELEFONICZNEJ, ROK 1937/38. https://mbc.cyfrowemazowsze.pl/dlibra/publication/edition/9884/.

- List of Subscribers of the Warsaw Telephone Network of the Polish Joint-Stock Telephone Company and the Government Warsaw District Network, 1938-1939. GRAPHIC PRINTING STUDIO “DOM PRASY” S.A. MARSZAŁKOWSKA 3-5-Ï, 1938. Originally published as SPIS ABONENTÓW WARSZAWSKIEJ SIECI. https://mbc.cyfrowemazowsze.pl/dlibra/publication/edition/9885/.

- List of Telephone Network Subscribers of the Capital City of Warsaw, Polish Joint-Stock Telephone Company, and the Warsaw District Network, 1939-1940. GRAPHIC PRINTING STUDIO “DOM PRASY” S.A., MARSZAŁKOWSKA 3/5/7, 1939. Originally published as SPIS ABONENTÓW SIECI TELEFONICZNEJ. https://mbc.cyfrowemazowsze.pl/dlibra/publication/11896/edition/9887.

- Official Telephone Directory for the General Government. Deutschen Post Osten, 1941. Originally published as Amtliches Fernsprechbuch. https://bc.radom.pl/dlibra/publication/1268/edition/1229.

- Official Telephone Directory for the General Government. Deutschen Post Osten, 1942. Originally published as Amtliches Fernsprechbuch für das Generalgouvernement. Urzędowa Książka Telefoniczna dla Generalnego Gubernatorstwa. https://bc.radom.pl/dlibra/docmetadata?id=1230.

- Official Telephone Directory for the General Government 1941. Druckerei der Postsparkarse, 1941. Originally published as Amtliches Fernsprechbuch für das Generalgouvernement, Ausgabe Mai 1941. Urzędowa Książka Telefoniczna dla Generalnego Gubernatorstwa, wydanie z maja 1941. https://mbc.cyfrowemazowsze.pl/dlibra/publication/edition/9818/.

- Official Telephone Directory for the Lublin District. Deutsche Post Osten, 1942. Originally published as Amtliches Fernsprechbuch für den Distrikt Lublin = Urzędowa Książka Telefoniczna dla Dystryktu Lublin. 1942. https://bc.umcs.pl/dlibra/publication/1901/edition/1736.

- Official Telephone Directory for the Posen District Regional Postal Directorate. Deutschen Post Osten, 1942. Originally published as Amtliches Fernsprechbuch für den Bezirk der Reichspostdirection Posen. 1942. https://bc.wbp.lodz.pl/dlibra/publication/77051/edition/73535.

- Official Telephone Directory for the Radom District. Deutsche Post Osten, 1942. Originally published as Amtliches Fernsprechbuch fur den Distrikt Radom. https://sbc.wbp.kielce.pl/dlibra/publication/13691/edition/13459.

- Official Telephone Directory for the Warsaw District. Deutschen Post Osten, 1942. Originally published as Amtliches Fernsprechbuch für den Distrikt Warschau. Urzędowa Książka Telefoniczna dla Dystryktu Warschau. https://mbc.cyfrowemazowsze.pl/dlibra/publication/edition/9817/.

Others Sources

- Batorski, Przemysław. “‘Treblinka Must Cease to Exist.’ Read the Account of the Rebellion at the Extermination Camp on August 2, 1943.” Żydowski Instytut Historyczny. Accessed December 23, 2025. https://www.jhi.pl/en/articles/treblinka-must-cease-to-exist-account-rebellion-extermination-camp-august-2-1943,3964.

- CODOH Forum Wiki. “The Burning of the Treblinka II Death Camp (Photographs).” December 27, 2025. https://wiki.codohforum.com/pages/index.php?title=The_Burning_of_the_Treblinka_II_Death_Camp_%28Photographs%29.

- DeathCamps.Org. “The Treblinka Station Master Franciszek Zabecki.” December 28, 2005. http://www.deathcamps.org/treblinka/zabecki.html.

- Flaws, Jacob. Spaces of Treblinka: Retracing a Death Camp. University of Nebraska Press, 2024.

- Flaws, Jacob. “The Treblinka Uprising.” The National WWII Museum | New Orleans, December 12, 2024. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/treblinka-uprising.

- Gontarek, Alicja. “The Military Action of the Home Army during the Rebellion in the Camp of Treblinka II in August 1943 – a Pre-Research Survey.” In Totalitarian and 20th Century Studies, vol. 3. Instytut Pileckiego, 2019.

- Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team. “Franciszek Zabecki – The Station Master at Treblinka: Eyewitness to the Revolt – 2 August 1943.” 2007. http://www.holocaustresearchproject.org/revolt/zabecki.html.

- Holocaust Historical Society. “Zabecki Station Master at Treblinka.” June 7, 2022. https://www.holocausthistoricalsociety.org.uk/contents/treblinkadeathcamp/zabeckistationmaster.html.

- Mattogno, Carlo. The “Operation Reinhardt” Camps Treblinka, Sobibór, Bełżec: Black Propaganda, Archeological Research, Expected Material Evidence. 1st ed. Holocaust Handbooks 28. Academic Research Media Review Education Group Ltd, 2024. https://holocausthandbooks.com/book/the-operation-reinhardt-camps-treblinka-sobibor-belzec/.

- Rucker, Jett. “Perfect Revisionism: The Vinland Map.” Inconvenient History 5, no. 3 (2013). https://codoh.com/library/document/perfect-revisionism-the-vinland-map/.

- Samuel, Monika. “Railwayman Franciszek Ząbecki. Memoirs of a Witness from Treblinka.” In Treblinka Warns and Reminds. Muzeum Treblinka, 2024. Originally published as Kolejarz Franciszek Ząbecki. Prace Wspomnieniowe Świadka z Treblinki.

- Samuel, Monika. Treblinka Station: Between Life and Death. Muzeum Treblinka. Niemiecki nazistowski obóz zagłady i obóz pracy (1941-1944), 2021. Originally published as Stacja Treblinka: między życiem i śmiercią: katalog wystawy. Muzeum Treblinka.

- Webb, Chris, and Michal Chocholatý. The Treblinka Death Camp: History, Biographies, Remembrance. Second, Revised an updated edition. Ibidem, 2021.

- Wikipedia, wolna encyklopedia. “Franciszek Ząbecki.” Accessed September 29, 2025. https://pl.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Franciszek_Z%C4%85becki&oldid=72696889.

- Wojcik, Michal. Treblinka 43: Revolt at the Death Factory. ePub. Znak litera nova, 2018. Originally published as Treblinka 43: Bunt w fabryce smierci.

- Ząbecki, Franciszek. “Minutes of the interrogation of Franciszek Ząbecki, the duty station Treblinka in 1941-1944. Treblinka Station.” In Treblinka: Research, Memories, Documents. Яуза, 1944. Originally published as Протокол допроса Францишка Зомбецкого, дежурного станции Треблинка в 1941-1944 гг. Станция Треблинка, 24 сентября 1944 г. State Archive of the Russian Federation (GARF 7445-2-134 pp. 79-85). https://docs.historyrussia.org/ru/nodes/354481.

- Ząbecki, Franciszek. “Plan of the Treblinka Extermination Camp: Execution.” In Treblinka Station: Between Life and Death, by Monika Samuel. Muzeum Treblinka. Niemiecki nazistowski obóz zagłady i obóz pracy (1941-1944), 1967. Originally published as Plan Obozu Zagłady Treblinka. Muzeum Treblinka. https://muzeumtreblinka.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Katalog-Stacja-Treblinka.pdf.

- Zabecki, Franciszek. “Providing help to Jews.” In Treblinka Station: Between Life and Death, by Monika Samuel. Muzeum Treblinka. Niemiecki nazistowski obóz zagłady i obóz pracy (1941-1944), 1967. Originally published as Udzielanie pomocy Żydom. Muzeum Treblinka. https://muzeumtreblinka.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Katalog-Stacja-Treblinka.pdf.

- Ząbecki, Franciszek. “Testimony about the Treblinka extermination camp.” January 19, 1965. Ghetto Fighters House Archives. http://www.infocenters.co.il/gfh/notebook_ext.asp?item=51626&site=gfh&lang=ENG&menu=1.

- Ząbecki, Franciszek. Wspomnienia dawne i nowe. PAX, 1977.

- Zaborski, Zdzisław. We stood by you, Warsaw: the history of the conspiracy and fighting of the VI District “Helenów” of Pruszków-Piastów-Ursus-Sękocin. Wyd. 1. Powiatowa i Miejska Biblioteka Publiczna im. Henryka Sienkiewicza, 2011. Originally published as Trwaliśmy przy tobie, Warszawo: historia konspiracji i walki VI rejonu “Helenów” Pruszków-Piastów-Ursus-Sękocin.

Endnotes

| [1] | Samuel, Stacja Treblinka. p. 35. |

| [2] | Ibid., p. 35, image caption. |

| [3] | Samuel, “Railwayman Franciszek Ząbecki […]” p. 237. |

| [4] | Ibid., p. 238, image caption. |

| [5] | Wojcik, Treblinka 43: Revolt at the Death Factory. Epub edition, illustrations section. |

| [6] | Harrison et al., Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka. p. 232, fn 431. |

| [7] | Flaws, “The Treblinka Uprising.” Image caption. |

| [8] | Batorski, “Treblinka Must Cease to Exist.” Image caption. |

| [9] | CODOH Forum Wiki, “The Burning of the Treblinka II Death Camp (Photographs).” |

| [10] | Zabecki, Wspomnienia dawne i nowe. Unnumbered pages, image inserts following p. 48. See also: Wikipedia, wolna encyklopedia, “Franciszek Ząbecki.” |

| [11] | Zabecki, “Franciszek Ząbecki, Testimony.” |

| [12] | Zabecki, Wspomnienia dawne i nowe. p. 85-86. In his memoirs, Ząbecki writes that Pronicki left in May. In his interrogation with the Soviets, he told them Kuźmiński took over in February 1943. |

| [13] | Ibid., p. 79. |

| [14] | Zabecki, “Interrogation of Franciszek Zabecki.” |

| [15] | Ibid., p. 125. |

| [16] | Ibid., p. 125. Ząbecki misremembers Jankiel Wiernik, despite claiming to have met him twice during the war. |

| [17] | Zabecki, “Testimony about the Treblinka extermination camp.” |

| [18] | For his account of meeting Wiernik, see Zabecki, “Plan of the Treblinka Extermination Camp: Execution.” See also Zabecki, Wspomnienia dawne i nowe. p. 82. |

| [19] | Ibid., p. 102. |

| [20] | Mattogno, The “Operation Reinhardt” Camps, p. 165. |

| [21] | The interviews from all except Lasowski are available on the Chronicles of Terror website and listed individually in the bibliography. Scans of Lasowski’s interview are available from the Arolsen Archives. |

| [22] | Zaborski, We stood by you, Warsaw. p. 490. |

| [23] | For a list of formations active in the Treblinka area at the time of the uprising, see Gontarek, “The Military Action of the Home Army.” |

| [24] | The full list of telephone directories consulted is included in the bibliography. |

| [25] | Zabecki, “Franciszek Ząbecki, Testimony.” |

| [26] | Zabecki, “Interrogation of Franciszek Zabecki.” Nothing like this is in any of his further testimony or accounts. |

| [27] | Rucker, “Perfect Revisionism.” |

| [28] | Webb and Chocholatý, The Treblinka Death Camp. p. 19. |

| [29] | Zabecki, Wspomnienia dawne i nowe. Unnumbered pages, image inserts following page 112. |

| [30] | Kuźmiński, “Józef Kuźmiński, Testimony.” |

| [31] | https://share.google/aimode/v49plQYMGemEEiMfK; that link was active only for a week, however. |

| [32] | See G. Rudolf, “Open-Air Pyre Cremations Revisited” and the sources quoted in it; https://codoh.com/library/document/open-air-pyre-cremations-revisited/ |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 2026, Vol. 18, No. 1

Other contributors to this document: Editor's Remarks: Germar Rudolf

Editor’s comments: