Fraud Exposed in Defamatory German Exhibition

Photo Exhibit of German Army Atrocities Shut Down

A highly publicized German exhibition of atrocities allegedly carried out by regular German army forces during the Second World War has been closed down in the wake of revelations that many of the harrowing photographs it displayed are deceitful. The organizers of “War of Annihilation: Crimes of the German Armed Forces, 1941–1944,” announced the shutdown on November 5, 1999, after ever more evidence had come to light proving that much of the controversial exhibit is fraudulent.

Since 1995 hundreds of thousands of visitors had viewed the exhibition, which appeared in more than 30 German and Austrian cities. Numerous secondary school classes were guided through it. Many of Germany’s most prominent social, political and business personalities endorsed the exhibit, which was designed to prove that regular German army (Wehrmacht) troops, and not just SS soldiers, carried out “Holocaust” killings of Jews and others.

“The Wehrmacht exhibition,” declared a leading Socialist party (SPD) politician in the German parliament, “is an important contribution to enlightenment. It gives a voice to the victims and, hopefully, to our consciences as well.” To applause from the entire body, a representative of the “moderate” CDU party declared: “I ask that such an exhibition about crimes committed by the German army be accepted with humility, in the spirit of the words of Ignatius, who said: truth against ourselves, that is humility.”

Most of the approximately 800 photographs in the exhibition are from Soviet-era Russian sources. More than half of the total are non-incriminating, while most of the 34 photos proven to be fraudulent or misrepresented actually show victims of the Soviets, and of other non-German forces. Exhibition organizer Hannes Herr also admitted that some of the photographs had been retouched. In some instances, photos taken from different angles of the same event or scene were displayed at different places in the exhibition with captions telling viewers that they showed atrocities at different locations. Also presented in the exhibition were documents that included phony confessions by Germans that had been extracted under torture from Soviets.

The shutdown postponed indefinitely the scheduled debut of an English-language version of the exhibition in New York City. Organizers announced their intention to re-open the exhibition after re-checking each of the hundreds of photographs.

A Polish Historian Speaks Out

A few “right-wing” German periodicals – including the weekly National-Zeitung and the quarterly journal Deutschland in Geschichte und Gegenwart – established early on that at least some of the photos in the anti-Wehrmacht exhibition were deceitful. Many examples of such deceit were also cited in a book published in 1999 by the FZ-Verlag of Munich: Bilder, die Fälschen: Dubiose “Dokumente” zur Zeitgeschichte (“Pictures that Falsify: Dubious ‘Documents’ of Contemporary History”).

However, it was only after two non-German scholars – one Polish and one Hungarian – incontestably identified misrepresentation and deceit among the exhibit photographs that “establishment” Germans felt emboldened to voice criticisms. Prof. Hans Moeller, for one, director of the Institute for Contemporary History in Munich, acknowledged that the exhibition was full of errors, adding that it would be irresponsible to show it in the United States.

Especially important in this process was the role of Bogdán Musial, a youthful Polish historian who works at the German Historical Institute in Warsaw. In an article published in the prestigious Munich historical quarterly, Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte, he established that some of the exhibit’s most gruesome photographs – allegedly depicting German army killings of Jews – in reality showed victims of mass killings by the Soviet security police (NKVD).

Just after the German invasion of the USSR in June 1941, Soviet authorities summarily shot many thousands of political prisoners, hastily burying their bodies in shallow graves or dumping them down well shafts. As Musial put it: “Beria’s order [by Stalin’s secret police chief Lavrenti Beria] was clear: no ‘mortal enemy of Communism’ should be freed by the Germans. Tens of thousands were liquidated by shots to the back of the neck or by beatings with sledge hammers. In some cases, the murderers threw hand grenades among the hapless victims, who had been herded together into prison courtyards … The perpetrators literally waded in blood …” In the town of Lutsk, for example, the Soviets killed about 2,000 people.

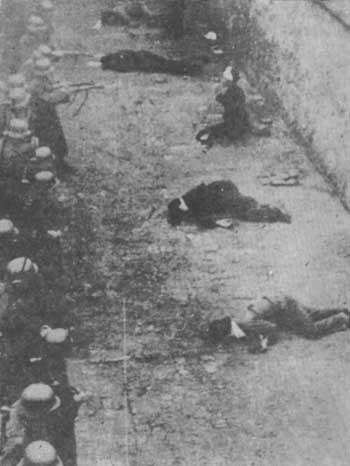

These two Wehrmacht crimes exhibition photographs purport to show German soldiers standing amid the bodies of Jews they had killed. In fact, these victims – most of them Ukrainians – had been killed in the town of Zloczow (Galicia) in late June 1941 by Soviet security police. The bodies were disinterred after German forces drove out the Soviets.

“… Before their flight from [the western Ukraine city of] Lviv [Lvov] in late June 1941,” wrote Musial, “the Soviets murdered some 3,000 to 4,000 prison inmates, most of them in the Brygidki prison. The victims were Ukrainians, Poles and Jews, as well as Soviet and even captured German soldiers.” After the Soviet withdrawal, Lviv residents went to the city’s main prison to search for missing relatives. “In the prison cellars,” relates Dr. Musial, “they saw layers upon layers of corpses … In the prison courtyard they found two mass graves.”

After Soviet forces fled from Lviv, the people of this ethnically mixed city took bloody revenge on the Jews (who generally had been ardent supporters of the Soviet regime). Many perished in this outburst of murderous rage. “There is, however, no indication that this pogrom was provoked by the Germans,” Musial notes.

What happened in the western Ukrainian town of Zloczów (Galicia) was typical of many others in the region. Following the Red Army takeover in late 1939, Soviet authorities arrested hundreds of “enemies of the people” there and deported them to Siberia and Kazakhstan. Then, in late June 1941, in the face of advancing German forces, Soviet security forces hastily rounded up 700 more allegedly anti-Soviet Zloczów inhabitants, and killed them over a five-day period with shots to the back of the neck. After German forces drove out the Red Army on July 1, 1941, they cooperated in digging up the mass graves of the victims.

In some places in this region, Musial notes, the Germans arrived just in time to rescue people who were about to be killed. “Altogether some 13,000 prisoners were liberated by the Germans.”

Musial compares the “Wehrmacht crimes” exhibit to the propaganda of the Communist regime in Poland. “The strength of this exhibition,” he has said, “lies in the weakness of its critics.”

As Musial explains, photographs of unearthed mass graves of Ukrainians and Poles killed by the Soviets were found by Red Army troops on the bodies of German soldiers who had fallen on the eastern front. These included some taken at Zloczów by a junior officer, Richard Worbs, who fell in 1944. Soviet authorities publicized such photographs as evidence of German atrocities. These same photos, with their deceitful misrepresentations, were acquired by the organizers of the German Wehrmacht crimes exhibition for display to hundreds of thousands of credulous viewers.

“Wehrmacht crimes” exhibition organizers Bernd Boll (left) and Hannes Herr (right), at its opening in the Kiel regional parliament in January 1999, with parliament president Heinz-Werner Arens in the middle.

In one exhibition photo, Musial explains, the corpses shown were actually Ukrainians who had been killed by the Soviet security police in Borislav (in Galicia, western Ukraine). The German soldiers seen in the photograph had helped unearth the bodies for identification. Another exhibition picture allegedly shows victims of a German massacre in Kraljevo (Serbia) in October 1941. In fact, the victims were Ukrainians and Poles killed by the Soviet NKVD in late June 1941 in a Lviv prison courtyard. “The victims were Ukrainians, Poles, Jews, Russians and German prisoners of war,” said Dr. Musial.

Among other apparently damning exhibition photos are some that show German soldiers standing among corpses “at a pogrom in Tarnopol.” In this case as well, the bodies are actually those of Ukrainian and Polish victims of the Soviet NKVD, which had been unearthed after the area came under German occupation.

“It is known that the regular German army carried out crimes,” Musial said in an interview. “It is impossible that among a million soldiers, and above all in the circumstances of that war, there would not have been crimes. But there were also countless decent soldiers.”

When Dr. Musial first made public his criticisms, the Wehrmacht exhibition organizers sought to silence him with a lawsuit and to discredit him with a smear campaign.

A Bold Hungarian Historian

Along with Musial, Hungarian historian Krisztián Ungváry played a major role in discrediting the “Wehrmacht crimes” exhibition. The 31-year-old Budapest scholar, who was named “military historian of the year” in 1998 by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, identified additional misrepresentations in a scholarly article.

In an interview with a Berlin newspaper, Ungváry spoke of “false photographs” and “false attributions.” He said that “90 percent of the exhibition must be altered.” Perhaps ten percent of the exhibition’s pictures showed German atrocities, he estimated, while another ten percent showed atrocities by Ukrainians, Finns, Hungarians or the Soviets. The remaining photos (about 80 percent of the total), he went on, showed no atrocities or crimes of any kind.

One of the exhibit’s most often cited photographs purports to show a German army execution squad preparing to shoot several young men. In fact, as Ungváry established, this photo depicts a Hungarian firing squad in the town of Stari Becej (in Vojvodina, which at the time belonged to Hungary) in the fall of 1941. At the time there were no German troops in the area. The doomed men are Communists who had been sentenced to death by a Hungarian military court for treason, murder and sabotage.

“The crimes of the Wehrmacht were dreadful,” says Ungváry, “but they were not unique. The Hungarian, Romanian and Soviet armies also carried out terrible crimes. This is also true of anti-Jewish excesses.”

Missing Context

Apart from its overt deceit by misrepresenting authentic photographs, the exhibition is a propagandistic fraud on a more fundamental level because it makes sweeping generalizations and fails to provide adequate historical context. A good example is the exhibit’s most familiar photograph (reproduced on the front cover of Germany’s leading news magazine, Der Spiegel), which shows German soldiers at an execution of several men in April 1941 in Panchevo, Serbia (Vojvoidina region).

What exhibition visitors were not told is that this was an execution of 18 Yugoslav army fighters who, disguised as civilians, had been involved in shootings of German soldiers. They were sentenced to death by a military court. This execution, however grim, was in conformity with internationally recognized military law. (Also unmentioned is the fact that when Yugoslav forces retreated from Panchevo, they took with them nine ethnic German civilians as hostages, who were then murdered in a nearby forest.)

“Victims of the massacre in Kraljevo, October 1941,” is the description given to this photo in the “Wehrmacht crimes” exhibition. It allegedly shows victims of a German massacre in Serbia. In fact, as Polish historian Musial established, these victims – mostly Ukrainians and Poles – had been killed by the Soviet NKVD in late June 1941 in a prison courtyard in Lviv (Lvov), western Ukraine.

Double Standard

The controversy over the exhibition once again underscores the double standard by which wartime Germany is routinely regarded. In contrast to the heavy stress by politicians and the media on victims of the Third Reich, especially Jewish Holocaust victims, there is comparative silence about victims of the Allies, especially those of America’s wartime partner, the Soviet Union.

No one demands, or expects, self-abasing apologies from America’s political leaders for the massive US support for Stalin during the Second World War.

While the public is constantly exhorted to “never forget” the victims of the Holocaust, we hear no such admonition for the vastly more numerous victims of Communism.

The scholars who identified falsifications in the Wehrmacht exhibition are – to use the pejorative label that is routinely applied to those who point out false Holocaust claims – “deniers.” Historians such as Musial and Ungváry “deny” the atrocities “proven” by the exhibition.

Jewish groups have often criticized Germans for their alleged failure adequately to come to terms with their Nazi past. But it is doubtful that political and social leaders in any other country would give their support to an exhibition that, in effect, indicts their grandfathers as criminals.

In today’s Germany, statements that call into question the official view of the Holocaust story can bring legal persecution. And truth is no defense. Several years ago, for example, German courts fined best-selling British historian David Irving 30,000 marks (about $21,000) for publicly saying what is now authoritatively conceded. He was punished for having told a Munich meeting that the structure in Auschwitz that has been portrayed for decades to tourists as an extermination gas chamber is a “dummy” (Attrappe).

Irving was found guilty of thus “disparaging the memory of the dead,” a German criminal code provision that effectively “protects” only Jews. The judge refused to consider any of the evidence presented by Irving’s attorneys, including a plea to permit the senior curator and archives director of the Auschwitz State Museum to testify in the case.

It is, of course, very unlikely that those responsible for the Wehrmacht exhibition will ever be charged, much less punished, for violating German laws against “insulting the memory of the dead” or against “popular incitement,” two of the criminal code sections that are routinely applied to “Holocaust deniers.”

One can be sure that organizers of a comparable exhibition of Allied or Zionist crimes, no matter how factually accurate, would doubtless have to reckon with criminal indictment and prosecution.

American newspaper reports about the exhibition’s revelations have tended to play down the scope of its misrepresentations, stressing that only a small portion of the photographs have been proven to be fraudulent. This is at least misleading, though, given that 70–80 percent the exhibition photos portray nothing at all sinister or criminal.

In an article about the exhibition revelations, the London Times warned: “The danger now is that Holocaust revisionists, who seize on all research blunders to bolster their arguments minimizing or denying the Holocaust, will try to argue that the German army was innocent of all war crimes.”

One of the most harrowing photos in the “Wehrmacht crimes” exhibition supposedly shows German troops executing civilians in Serbia in the fall of 1941. Hungarian historian Kriszthin Ungvary has established that this picture actually shows an execution by Hungarian troops in Stari Becej (which at the time belonged to Hungary) of Communists who had been sentenced to death by a Hungarian military court for treason, murder and sabotage.

Germany’s Climate of Intimidation

This deceitful and defamatory traveling exhibition could only have attained the stature it did with the thoughtless or cowardly cooperation of German historians and politicians. They knew, or should have known, how fundamentally mendacious this exhibit was, but many Germans today keep their mouths shut out of fear of being labeled a “revisionist,” “nationalist,” or “right-winger.”

This is a consequence of a climate of intellectual repression, in which scholars are obliged to abide by a restrictive “political correctness,” or risk public defamation or even legal persecution for daring to write or publish anything that might seem to “exonerate” the Third Reich regime.

As Budapest historian Ungváry has pointed out:

It is certainly not easy for a German scholar to present substantive criticisms on this topic without immediately being labeled a right-winger or being suspected of supporting the wrong side. I find this very worrisome, and it is unfortunate that no one does anything about this in Germany. Criticism of the exhibition has largely been left to the right-wing extremists.

The influential German daily Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung wrote that the revelations highlighted the “intellectual climate” in today’s Germany, which made possible a propagandistic enterprise with such prestigious backing. On another occasion the daily newspaper commented: “The abundance of the exhibition organizers’ errors, mistakes and negligence, proven by researchers, is devastating. One is at a loss for words, considering that this is about such a serious subject. One comes across something comparable only in government-organized disinformation campaigns.”

“Why didn’t German historians expose the many mistakes and misrepresentations in the Wehrmacht exhibition?,” wrote the editor of the German news magazine Focus. “History professors provide an answer only when we promise not to reveal their names: ‘Every historian immediately saw just how shoddy and slanted the exhibition was set up, but who has any desire to allow himself to be publicly ruined?’ The persecution of dissident thinkers has had quite an impact.”

Commenting on the exhibition controversy, Dr. Musial expresses some hope for the future:

I have the impression that the Germans have difficulties dealing with certain realities. A climate of consternation dominates, and this is certainly good for people such as Hannes Heer or Daniel Goldhagen. One does not really dare to question their views on scholarly grounds. Whoever dares to tackle these things without qualms, as I have, risks being labeled a revisionist. On the other hand, the tremendous response to my work gives me hope that finally in Germany people will begin to discuss, substantively and unhampered, this chapter of contemporary history.

Perhaps the most widely-reproduced photograph in the anti-Wehrmacht exhibition is this one, which shows an execution by German troops in April 1941 in the town of Panchevo in the Vojvodina region. This was an execution of 18 Yugoslav army fighters who, disguised as civilians, had been involved in shootings of German soldiers. They were sentenced to death by a military court. As grim as it was, this execution was entirely in accord with internationally-sanctioned military law.

(Sources: W. Hackert, “Diffamierung der deutschen Wehrmacht,” Deutschland in Geschichte und Gegenwart [Tübingen], Feb. 1998, pp. 22–29; “Leichen im Obstgarten,” Der Spiegel, Jan. 25, 1999, pp. 52–53; Klaus Sojka, Hrsg., Bilder, die Fälschen: Dubiose “Dokumente” zur Zeitgeschichte [Munich: FZ-Verlag, 1999]; Ungváry interview in Berliner Morgenpost, June 14, 1999; “Geschichtsverzerrung,” Deutschland in Geschichte und Gegenwart, Sept. 1999, p. 14; Musial interview, “Die Spitze eines Eisbergs,” Welt am Sonntag, Oct. 24, 1999; “Reemtsmas Spukhaus bricht zusammen,” National-Zeitung [Munich], Oct. 29, 1999, pp. 3–4; R. Boyes, “Photo errors arm German neo-Nazis,” The Times [London], Nov. 2, 1999; “‘Mörder-Wehrmacht’: Die Lüge stirbt,” National-Zeitung [Munich], Nov. 5, 1999, pp. 1, 4, 11; “Beweismittel gefälscht, Urteil richtig,” National-Zeitung [Munich], Nov. 12, 1999, pp. 3–6; “Wehrmacht: Neue Fälschungen,” National-Zeitung [Munich], Nov. 19, 1999, pp. 1, 6.

A Munich publisher, FZ-Verlag, recently issued a 416-page German-language book about the Wehrmacht exhibition, Die Wahrheit über die Wehrmacht: Reemtsmas Fälschungen widerlegt (“The Truth about the Wehrmacht: Reemtsma’s Frauds Debunked”). It is available from Deutscher Buchdienst, Postfach 60 04 64, 81204 Munich, Germany.

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 18, no. 5/6 (September/December 1999), pp. 6-11

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a