The Myth of Flames Rising from Crematoria Chimneys

Did the crematoria chimneys of the National-Socialist concentration camps belch out enormous flames, as many deportees claim in their accounts? Revisionists doubt it, and they’re not alone. An author such as Jean-François Forges, hardly suspected of revisionism, issued a warning of sorts in Éduquer contre Auschwitz (ESF Éditeur, Paris, 1997, p. 30):

“The guardians of memory must do their own work and denounce the complacent and unhealthy fantasies that consist in monstrously multiplying the millions of dead, the flames and the horrors of all kinds. We must stop allowing the ill-intentioned to cast suspicion on all testimonies. It is inconceivable that a theory as weak as Holocaust denial can endure and still appeal. The meticulous rigor of all those who want to talk about Auschwitz is one of the conditions for finally seeing an end to this regular and unbearable return of the scandals orchestrated by the negationists.” (Emphasis added)

A few pages further on, he writes (pp. 40f.):

“Elie Wiesel was not yet fifteen when, after an exhausting journey, he reached the ramp at Birkenau. He was still in the carriage when someone shouted: ‘Jews, look! Look at the fire! The flames, look! And as the train stopped, this time we saw flames coming out of a high chimney into the black sky.’ 77 Numerous witnesses speak of the flames coming out of the chimneys.78 These accounts must no doubt be understood as a symbolic description of the hell into which the deportees find themselves plunged, according to the traditional images of the world of suffering and damnation.”

And the full text of note 78 is as follows:

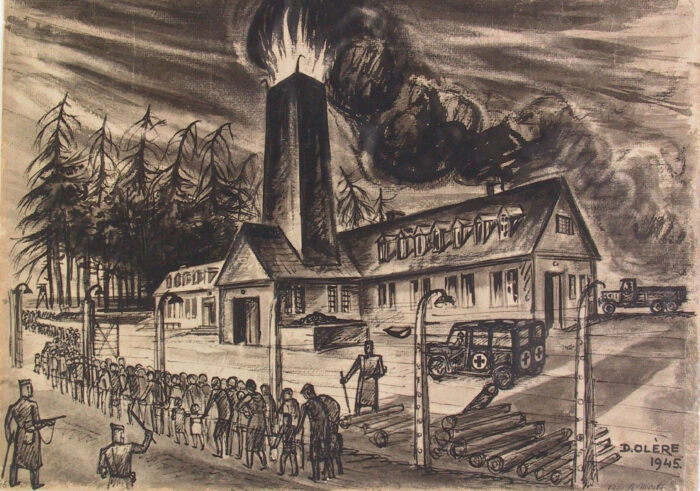

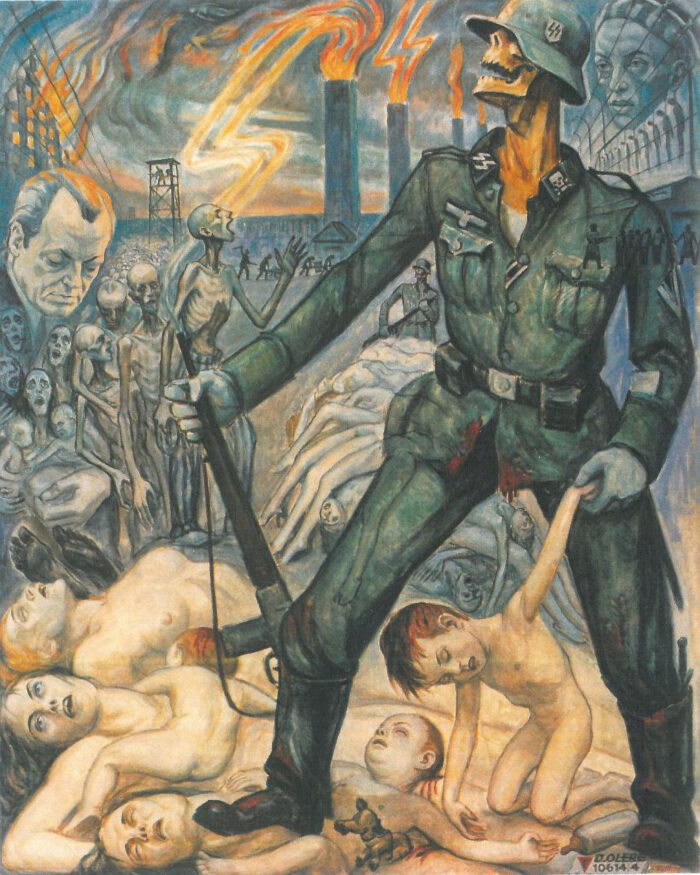

“For example, among many others, Jorge Semprun who ends his book about Buchenwald, L’écriture ou la vie, page 319, with the sentence: ‘On the crest of the Ettersberg, orange flames protruded from the top of the crematorium’s squat chimney’, or the drawings by David Olère, Un peintre au Sonderkommando d’Auschwitz, pages 36, 50, 51. Was it sparks, the ignition of residual gases? The testimonies are too numerous to be mere hallucinations. But these images are sometimes amplified. Myriam Anissimov evokes these flames several times in her book on Primo Levi. She dramatizes a scene evoked in Si c’est un homme, about Chant d’Ulysse and Dante’s Inferno, imagining that at the same time ‘several thousand men, women and children’ were being killed in the gas chambers, and that the chimneys ‘spat out human flames 10 meters high’ (page 263). She goes on to write that the chimneys ‘spewed gigantic red flames day and night, visible for miles’ (page 272), visible even ‘from the Buna factory’ (page 299). These excesses of imagination are astonishing in a book dedicated to Primo Levi, a model of rigor, measure and scrupulousness, whose ‘every word is weighed on the precision scales of the laboratory’ (page 409). The image of fire, however, is engraved in the memories of those who witnessed the death machines as a symbol of infernal creation. At the beginning of the film and book Shoah, on page 18, Simon Srebnick describes what he saw at Chelmno. He says: ‘There were two huge furnaces… and then the bodies were thrown into these furnaces, and the flames went up to the sky.’ Lanzmann asks for confirmation: ‘To the sky?’ Srebnick answers yes, the flames went up ‘to the sky’. The image of fire rising to the sky is probably the strongest to produce truth about the gigantism and horror of the infernos.”

Jean-Claude Pressac, in his “Enquête sur les chambres à gaz” (“Investigation into the Gas Chambers”), Les Collections de L’Histoire, No. 3, Auschwitz, la Solution finale, pp. 34-41, writes (p. 41):

“We know that the allegations made by Holocaust deniers focus essentially on three points. We won’t return here to their questioning of the number of Jewish victims. But as far as the other two points are concerned – the non-existence of homicidal gas chambers and the low incineration efficiency of the Topf furnaces – they have been or will be swept aside by the Topf documents. On the other hand, they contradict, for example, Birkenau survivors’ accounts of columns of smoke and flames spewing from the crematoria chimneys. A crematorium doesn’t smoke because manufacturers have forbidden it since the first European congress on cremation held in Dresden in 1876. [Note: F. Schumacher, Feuerbestattung, J. M. Gebhardt’s Verlag, Leipzig, 1939, pp. 20 and 21]. Subsequent regulations confirmed this. For Topf, it was a constant obsession from the outset to build smokeless fireplaces, so much so that the first two German patents (No. 3855 registered on March 16, 1878, and No. 7493 on February 14, 1879) [note: Institut national de la protection industrielle, antenne documentaire de Compiègne] applied for by Johann Andreas Topf were for smokeless fireplaces whose advertising prospectus promised future customers that ‘Topf-style fireplaces ensure complete, smokeless combustion.’ Prüfer was obliged to respect this double imperative (professional and regulatory), even with concentration-camp furnaces, as he confirmed to Soviet Smersh officers questioning him on March 5, 1946. This is why none of the aerial photos of Birkenau taken in 1944 by the US Air Force show smoke coming out of the six chimneys of the four crematoria.”

Other than the fact that eyewitness accounts are decidedly unreliable, as revisionists have been saying for fifty years, and as any historian worthy of this name should know, what can we conclude from all this? To illustrate this self-evident truth, here are some excerpts from deportees’ accounts of flames belching from the crematoria chimneys. Until proven otherwise, these flames are just one of the many myths of the concentration-camp world. We would be grateful if readers could provide us with other examples of stories about flames.

1945. Denise Dufournier, Souvenirs de la maison des morts, preface by Maurice Schuman, Hachette, Paris, 1945.

P. 50f.: (Ravensbrück) “But a glow more fiery than the others rose like a firework, falling and rising to the sky in a continuous stream. It was the great red flame escaping from the crematorium.”

1947. Georges Straka, “L’arrivée à Buchenwald,” De l’Université aux camps de concentraton. Témoignages strasbourgeois, Les Belles Lettres, Paris, 1947.

P. 82: “Later, we became accustomed to his presence in the very center of our prison, and even to its red flames rising several meters above its chimney on winter evenings or during interminable roll calls lasting up to 9 or 10 hours.”

1954. Henry Bulawko, Les Jeux de la mort et de l’espoir: Auschwitz-Jaworzno, new revised and expanded edition, preface by Vladimir Jankélévitch, Recherches, [Fontenay-sous-Bois?], 1980 [1st ed. 1954], 188 p.

P. 162f.: “The chimneys smoke incessantly, the sky [p. 163] at Birkenau is perpetually illuminated by the flames coming out of the four chimneys where millions of anonymous bodies are consumed.”

P. 180: “Who would have thought that in the heart of twentieth-century Europe, in the land of Kant and Marx, Beethoven and Goethe, the death camps and the smoking chimneys of their crematoria would spring up?”

1956. Lucie Adelsberger. Auschwitz. Ein Tatsachenbericht, Lettner, Berlin, 1956.

P. 82: “Officially, we were forbidden to know about the practice of this selection, even when the flames rose to the sky before our eyes and we were on the verge of suffocating due to the smell of fire and smoke.” (Quoted by W. Stäglich in his book on Auschwitz.)

1973. Viktor Frankl, Un psychiatre déporté témoigne, Éditions du Chalet, [Lyon], 1973 (Auschwitz).

P. 34f.: “A hand shows me a chimney only a few hundred yards away, and from it rises a [p. 35] high, sinister jet of flames, which dissolves into a dark cloud of smoke.”

1973 [?]. Germaine Tillion, Ravensbrück, Le Seuil, Paris, 1973.

P. 58: An elderly French Gypsy recounts what she claims to have seen in Auschwitz. “When we arrived at Auschwitz, we were put in a big wooden barracks with black gravel on the floor and nothing else […], and through the cracks in the planks, we could see big flames, all red, but we didn’t know what they were.”

1976. Fania Fénelon, Sursis pour l’orchestre, testimony collected by Marcelle Routier, co-published by Stock/Opera Mundi, 1982 [1st ed. 1976], Paris (Auschwitz).

P. 33: “It’s strange, you can’t see the sky; it’s as if it doesn’t exist. I have the impression that between it and us, there’s a huge smoke screen. Look at the horizon, it’s red, you can see a flame.”

P. 261: “Summer is here. The weather has been really fine for a few days now, with the heavy cloud of smoke from the crematoria stagnating in the warm air. We’re short of air, but occasionally catch a glimpse of the sun.”

P. 283: “We’re surrounded by thick smoke that hides the sun from us, and the awful smell of burnt meat suffocates us.”

P. 343: “Above the crematoria, the heavy smoke indicates that they are full to the brim, that they can absorb no more, so we leave them there, with their children, to await their turn.”

P. 356: “Since the alerts, the light has been reduced, and only the glowing sky still shows us the camp.”

1979. Professeur Gilbert-Dreyfus (Gilbert Debrise: pseudonym), Cimetières sans tombeaux: récit, Plon, Paris, 1979 (Mauthausen).

P. 22: You’ll never go through that door again,” and pointing to the glowing red belching of the crematorium: “The only way out of here is through the chimney.”

1979. Renée Louria, Les Russes sont à Lemberg, Gallimard, Paris, 1979 (Auschwitz-Birkenau).

P. 17: “[…] as the crematorium’s tall flames rose into the sky, and the smell of roasted flesh permeated the atmosphere […].”

P. 64: “[…] tall, glowing flames from the crematorium, crackling in the night […].

P. 68: “The chimneys of the crematorium no longer belched their flames of death, and were barely visible in the dense night.”

P. 116: “[…] and pushing me towards the window, she showed me the great chimney from which tall flames were escaping, which reminded me of those of the oil refineries I had seen one day passing near Rouen […].”

p. 125: “From the chimneys of the crematoria rose a tall, clear flame that emblazoned the camp with an eerie orange-red light. A penetrating smell of roasted flesh filled the atmosphere.”

P. 196: “The flames from the crematoria once again shot their fiery crests skyward.”

P. 212: “Here in this hell, we were given a slice of brown bread, while the crematoria spat out their fiery flames relentlessly.”

P. 227: “The crematorium flames rose high and sinuous into the sky with a mournful crackling sound. Flames descended in bouquets to the earth, like the incandescent flowers of a firework display.”

P. 229: “The crematoria lit up the camp with an apocalyptic light. […] In the red glow that engulfed the camp […].”

P. 240: “The crematoria were still spitting out their flames of death. Behind the barbed wire, just a little way back, children playing in the grass, waiting for the moment to go to the gas chamber.”

P. 253: “[…] the tall flames of the crematoria!”

1980. Jorge Semprun, Quel beau dimanche!, Éditions Grasset, Paris, 1991 (1sr ed. 1980), series Les cahiers rouges (Buchenwald).

P. 15: “The calm smoke over there was from the crematorium.”

P. 46: “[…] you could also see the crematorium chimney. It was smoking quietly. Pale gray smoke rose into the sky.”

P. 59: “[…] the light smoke from the crematorium […].”

P. 114f.: “The smoke from the crematorium is pale gray. They mustn’t have a lot of work at the crematorium to produce such light smoke. Either that, or the dead burn well. Very dry dead, corpses of friends like vine shoots [p. 115]. They give us this last flower of gray smoke, pale and light. Friendly smoke, Sunday smoke, no doubt.”

P. 124: “Perhaps the birds couldn’t stand the smell of burnt flesh, vomited over the landscape in the thick fumes of the crematorium.”

P. 180: “The crematorium chimney always smokes quietly.”

P. 239: “[…] The smoke from the crematorium rose into the sky […].”

P. 241: “[…] the smoke from the crematorium […].”

P. 253: “If they had turned their heads, they would have seen the crematorium building, its massive chimney from which the bitter, icy wind blew the smoke at times.”

P. 294: “[…] the haunting smell of the crematorium.”

P. 310: “I look distractedly at the crematorium chimney, noticing that the light gray smoke of the early morning has become thicker.”

P. 313: “[…] as light as crematorium smoke […].”

P. 329: “[…] in the pale December sky where crematorium smoke floats.”

P. 332: “[…] the calm gray smoke that was not crematorium smoke […].”

1981. Walter Laqueur, Le Terrifiant Secret. La “solution finale” et l’information étouffée, Gallimard, Paris, 1981.

P. 33: “Adolf Bartelmas, a railroad employee at Auschwitz, testified at the Auschwitz Trial, held in Frankfurt many years later, that the flames could be seen from fifteen or even twenty kilometers away, and that people knew it was humans being burned. Kaduk and Pery Broad, who appeared at the same trial, were even more categorical: when the chimneys were working, the flames were five meters high. The station, full of civilians and soldiers on leave, was covered in smoke, and there was a sweet smell everywhere. According to Broad, the clouds of black smoke could be seen and smelled from miles away: ‘The smell was absolutely intolerable…’”

1983 [?]. Edmond Michelet, Rue de la liberté: Dachau 1943-1945, Le Seuil, Paris, 1983 (reprint).

P. 187: “[…] the glowing chimney of the crematorium spitting fire night and day, spreading a smell of corpses that seemed to follow them here.”

1986. André Courvoisier, Un aller et retour en enfer, France-Empire, Paris, 1986 (Sachsenhausen).

P. 55: “[…] they made their way to the crematorium, from which an enormous amount of smoke was constantly pouring out, smelling indefinable when the wind blew it back into the camp.”

1987. Primo Levi, Si c’est un homme, translated from Italian by Martine Schruoffeneger, Julliard, Paris, 1987 (Auschwitz). In the appendix added in 1976.

P. 200: “[Giuliana Tedeschi] pointed out to me that from the window you could see the ruins of the crematorium; in those days you could see the flame at the top of the chimney. She had asked the elders, ‘What is this fire?,’ and was told, ‘It’s us who are burning.’”

1988 [?]. Margarete Buber-Neumann, Déportée à Ravensbrück: prisonnière de Staline et d’Hitler, Le Seuil, Paris, 1988.

P. 195: “[… Anicka] looks very upset and asks me to go and have a look out of the window. I see a tall column of fire rising above the cell building. I don’t immediately understand what could be burning. Then, all of a sudden, I make the connection with the crematorium.”

P. 196: In the winter of 1944-1945, the columns of fire coming out of the chimneys behind the cell block came to replace the wisps of smoke in the daily landscape of Ravensbrück.

P. 203: The end seemed very near, yet the crematoria chimneys continued to spit their flames and Winkelmann to choose his victims.

1990. Annette Kahn, Robert et Jeanne: à Lyon sous l’Occupation, Payot, Paris, 1990 (Auschwitz).

P. 136f.: “In my block, 12A, where most of us were non-Jews, we were strictly forbidden to turn our heads towards the crematoria, which belched out very tall, very straight flames. Like all the other blocks, ours was equipped with openings, sealed by boards with gaps in between. We weren’t allowed to hear or see anything we might repeat, so we were forbidden to turn our eyes towards the chimneys, on pain of following the same path. But we were fascinated, imagining what was going on in there, thinking that perhaps at the same moment, a friend, a sister, a father… I still shudder. So [p. 137] we were glued, our eyes against the slits, contemplating with horror this column of black smoke that provided a plume above the red flame.”

P. 150: “It’s over, that awful nightmare symbolized in the most secret of all by those chimneys belching fire and smoke is far away now, and every turn of the wheel makes it vanish a little more.”

1991 [?]. Béatrice de Toulouse-Lautrec, J’ai eu vingt ans à Ravensbrück. La victoire en pleurant, Perrin, Paris, 1991 [1st ed. 1946 ?].

P. 127 [you also know] that there is a crematory oven whose flame escaping from the chimney too often reddens the sky.

P. 270: The days are getting longer, the morning call seems shorter, and yet the crematorium flame is redder than ever, and the selections don’t leave us a moment’s rest.

P. 295 [and I think] […] of the red flame that escapes night and day from the high chimney. […]

1992. Sylvain Kaufmann, Le Livre de la mémoire: au-delà de l’enfer, preface by Robert Badinter, Jean-Claude Lattès/Stock, Paris, 1992 (Auschwitz).

P. 123: “His daughter was gassed on arrival. Max gradually brings me up to speed on what Auschwitz is like, and confirms that the reddish glow in the sky is a sign of the crematoria’s non-stop activity.”

P. 170: “[…] on the way to one of the gas chambers, […] we see the reddish glow of the crematoria every night, and smell the smell of burning flesh all the time.”

P. 396: “[…] asphyxiating trucks. […] At night, the glowing, sinister lights tore the sky and the hearts of those who knew what they meant.”

1992. Nadine Heftler, Si tu t’en sors…: Auschwitz, 1944-1945, preface by Pierre Vidal-Naquet, La Découverte, Paris, 1992 [written in 1946]

P. v (preface by Pierre Vidal-Naquet): “Nadine Heftler has nothing new to tell us about the gas chambers – since, shamefully, some people have tried to erase them from history – she simply saw, like so many others, the flames gushing out of the crematorium, and she knew early on, on October 22, 1944, that her mother had been a victim.”

P. 42f.: “Mom and I were immediately struck by the enormous flames coming out of a very tall chimney that looked like a factory chimney. Although astonished, we thought it was a chimney fire, and didn’t worry too much about it. In reality, it was the crematorium!”

P. 123: “[…] and, at night, the great red flames had ceased to light up the squalid camp.”

1993. Liana Millu, La Fumée de Birkenau, translated from Italian, preface by Primo Levi, Éditions du Cerf, Paris, 1993, Sseries Toledot-Judaïsmes.

P. 7 (preface): “[…] the haunting presence of the crematoria, whose chimneys, located right in the middle of the women’s camp – impossible to evade or deny – corrupted the days and nights with their unholy smoke […].”

P. 31: “[…] muddy, shifting sands that the light from the nearest crematorium illuminated with the reflection of its high flames;”

P. 36: “With an angry gesture, I pointed in the direction of the crematoria. They were all lit, streaking the foggy night with their tall flames; […]. With my face turned towards the bright flames, as if suspended in the darkness, I watched, …”

P. 65: “[…] the heavy wisps of crematoria […] little white light smoke […] heavy smoke from some selection among the old […].”

P. 70: “‘How it flames! Lord God, how it flames! […]’

We saw the night sky lit up in red and glittering with the enormous flames that rose ceaselessly from the little towers of the crematoria. The camp was thus dominated by a high crown of fire visible from the houses of Auschwitz, from those of the peasants and from the distant villages.

‘Tonight, there’s a lot of fire in Birkenau,’ these people might have said. […]

The flames rose so high that they lit up the camp’s alleyways. Reflections danced on the mud and puddles.”

P. 71: “Their faces reflected the glow of the flames […] human flesh given over to the flames […].”

P. 73: “‘over there,’ where a few tongues of flame were still flickering […].”

P. 108: “[…] the smoke from the crematoria hung in the heavy air […].”

P. 110: “[…] the smoke from the nearest crematorium.”

P. 117: “On the Birkenau side, some black smoke hung in the heavy air.”

P. 175: “[…] we dug ditches next to the crematoria to dispose of the excess ashes; […] we could see the smoke, so black, so heavy that it could hardly dissolve forever into nothingness.”

P. 177: “[…] and all the while, the crematorium continued to smoke, and bits of ash fell on my head.”

P. 179f.: “A little smoke came from the Birkenau side, and the wind carried it over Auschwitz. […] [p. 180] And it was all smoke. Smoke […].”

1995. Denise Holstein, « Je ne vous oublierai jamais, mes enfants d’Auschwitz… », Éditions no 1, Paris, 1995. series Témoignage.

P. 74: “As I come out [of the infirmary], we are directed to the other end of the camp. The sky is red, the smell is appalling, the air is unbreathable. Huge flames shoot out of the chimneys. We’re put up in a barracks just across the road. We spend a fortnight there.

1995. Nelly Gorce, Journal de Ravensbrück, foreword by Lucien Neuwirth, Actes Sud, Arles, 1995.

P. 104: “The maw of the monster [i.e. the crematorium] is, however, imperiously greedy; it needs its daily ration of human flesh.

High and gloomy, defying the world and humanity, blood-red flames rise into the sky, surrounded by a halo of thick, black smoke. The atmosphere is charged with the sickening smell of charred flesh, which lingers forever.

[…] And in the thick night, torn by these bloody lights, we feel terror and dread slowly rising within us.”

P. 108: “Sometimes, on arrival, a sorting takes place: the strongest are kept for camp work, and if they ask their tormentors about the nature of these gigantic flames violating the sky, they are told:

– It’s the bakery!

Strange bakery.”

P. 144: “Tonight, the flames from the crematorium rise high into the night, like a gigantic, devouring fire.”

P. 160: “From time to time, the glow of the crematoria streaks the sky, they are in full output, the nauseating smell forces me to leave the window.”

1996. Paul Steinberg, Chroniques d’ailleurs: récit, Ramsay, Paris, 1996.

P. 114f.: “The crematoria are under full load twenty-four hours a day. According to reports from Birkenau, we burned three thousand, then three thousand and five [hundred], and last week up to four thousand corpses a day. The new Sonderkommando is doubled up to monitor the gas chamber right through to the furnace, day and night. The chimneys let [p. 115] out ten-meter-high flames, visible at night for miles around, and the pungent smell of burning flesh reaches as far as the Buna.”

1996. Françoise Maous, Coma: Auschwitz, no A.5553. Récit, preface by Pierre Vidal-Naquet, Le Comptoir éditions, 1996.

P. 46: “[…] and his hand went up to the tall chimney of the brick building, from which a large flame was coming out. We noticed it, because when we called out, our eyes were turned towards it. We thought it was the crematorium where the dead were burned.”

P. 47: “Everything that I didn’t understand, all the terror that lay dormant inside me, everything that had seemed inexplicable since my arrival, was illuminated by the sinister glow of the giant crematorium; silently, I tried to realize this terrifying revelation.”

P. 89: “Tomorrow, at roll call, we would see the crematorium’s flame rise high, very high, illuminating us; the chimney would smoke, indicating to those who hadn’t seen that a convoy had arrived yesterday.”

P. 163: “The flames were so high that we could see them from our dormer windows, and we wondered if our turn was coming […].”

1997. Elisa Springer, Il silenzio dei vivi. All’ombra di Auschwitz, un racconto di morte et di resurrezione, Marsilio Editore, Venice, 1997.

P. 67f.: “Raising my eyes to my right, beyond the birch trees, the sky was lit up as if in broad daylight: great luminous flames licked the air, while a pungent odor spread, penetrating me. […]. That unbearable, acrid smell of burning sulfur never left me. I can still smell it today. I recognize the smell of death: it brought me closer to life. […]. Trembling with fear, we stared at the bright flame that reached for the sky and lit it up as if in broad daylight: all the water that fell on Birkenau that night was not enough to extinguish that flame.”

P. 70: “It was only after a few days’ stay in these places that everything began to make sense, even that long chimney that gave off tall flames and the acrid smell of burning flesh, one of the many sadly inseparable travelling companions of my existence”.

1997. Didier Epelbaum, Matricule 186140, histoire d’un combat, Éditions Michel Hagège, Boulogne-Billancourt, 1997. (The deportee interviewed in the book is Pierre Nivromont, deported from France for acts of resistance.)

P. 69: “And we always saw trucks coming night and day, non-stop, dumping people behind a kind of hedge. They would go down into the basements, and we never saw a single one of them come back up, except through the abominable red smoke.” (Birkenau)

P. 88: “When it was working hard, there was a red glow above those chimneys, it was really eerie.” (Buchenwald)

P. 117: “Didier Epelblaum: ‘One saw a flame coming out?’

Pierre Nivromont: ‘When the furnaces are going full blast, you can really see a red tongue coming out above the chimney. […] Because the Germans feared that the red flame would serve as a landmark, a milestone on the path of the bombers. […] In normal times, when this flame came into view, we’d say […]. That smoke, we saw it all the time, but we managed to be completely immune to the smell.’”

2000 [?]. Testimony of C. Kalb, collected by the Commission de l’histoire de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale and stored at the Institut d’histoire du temps présent. Excerpt reported in Michael Pollak, L’Expérience concentrationnaire. Essai sur le maintien de l’identité sociale, Éditions Métailié, Paris, 2000.

P. 193: “We knew we were there to die, and we resigned ourselves to it. The first few days, the crematoria with their big red flames struck us a lot, but afterwards we didn’t pay any attention to these things at all.”

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 2023, Vol. 15, No. 4; Updated version of Jean Plantin, “Le mythe des flammes qui jaillissaient des cheminées des crématoires,” Akribeia, No. 6, March 2000, pp. 23-32; www.vho.org/F/j/Akribeia/6/Akribeia23-32.html

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: