A Major Revisionist Breakthrough in Russia

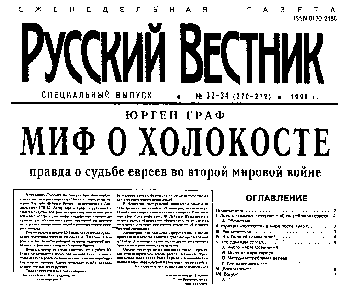

Under the front-page headline, “The Myth of the Holocaust: The Truth About the Fate of the Jews in the Second World War,” the Moscow paper Russkii Vestnik (“Russian Messenger”) has devoted an entire special issue to an effective revisionist analysis of the Holocaust extermination story.

This special issue of the Moscow paper Russkii Vestnik is devoted to a lengthy revisionist dissection of the Holocaust extermination story by Swiss historian Jürgen Graf. The front-page headline reads: “Myth of the Holocaust: The True Fate of the Jews During the Second World War.”

Written by Swiss historian and educator Jürgen Graf, this is the first serious work of revisionist scholarship on the Holocaust issue to receive mass distribution in Russia. Some 200,000 copies were sold between September 1996 and February 1997, both as a special issue of Russkii Vestnik and as an attractive 123-page booklet. Graf’s well-organized and carefully referenced essay debunks numerous specific Holocaust claims, while introducing readers to the work of such revisionist specialists as Robert Faurisson, Carlo Mattogno, Arthur Butz, Enrique Aynat and Fred Leuchter.

Introducing Graf’s essay is a front-page editorial note that condemns the “ghastly crimes committed against the Jews” by the “Hitlerites.” At the same time, though, it stresses that Jewish wartime losses have been greatly and purposefully exaggerated.

The editorial also introduces readers to historical revisionism, which is not well known in Russia. “On the basis of purely scholarly research,” relates the first paragraph, the Institute for Historical Review in the United States “debunks historical myths.” It continues:

The revisionist school of historians, which has been in existence for several decades in the West, on the basis of scrupulously examined documents and eyewitness accounts, was the first to question the assertions of the Zionists. The USSR and Russia were unaware of the existence and views of the revisionist school because we had not yet approached the problem in that way.

“Characteristically,” the editorial relates, “the main ‘arguments’ used against the revisionists have been court suits and terror,” citing the cases of such individuals as Robert Faurisson, Thies Christophersen, Ernst Zündel and Wilhelm Stäglich. “This alone suggests that the enemies of revisionism simply do not have any other kind of arguments.”

In a sympathetic page-two preface to Graf’s essay, Russian historian Dr. Oleg A. Platonov writes of the “myth of the ‘Holocaust,’ namely, that six million Jews were allegedly put to death in gas chambers during the Second World War.” This myth, he continues, “has taken hold in the mass mind with particular force,” with the aim of encouraging non-Jews to “feel a sense of guilt, repent and pay restitution.” He goes on:

The myth of the Holocaust insults humanity because it portrays the Jewish people as the main victims of the last war, even though the Jews in fact suffered not more, but less than other peoples who were caught up in that murderous conflict … Humanity paid for the war with 55 million human lives, in which the real – not the mythical – number of Jewish victims was not six million, but rather about 500,000, as the calculations of specialists show …

“On the wave of the myth of the Holocaust,” Platonov adds, “the state of Israel was established illegally and against the will of the Palestinians.” Both Graf and Platonov are members of this Journal’s Editorial Advisory Committee. (See the May–June 1997 Journal, pp. 19–20.)

To satisfy the public appetite for revisionism in Russia, translations of several revisionist writings are in the works, including a Russian edition of the book-length analysis of Israel’s “founding myths” by French scholar Roger Garaudy (reviewed in the March–April 1996 Journal, pp. 35–36).

This special Russkii Vestnik issue was cited favorably in the Moscow newspaper Pravda (January 24, 1997). Valentin Prussakov’s Pravda article, “Jews at the Origins of Nazism,” discusses the role of Jews and half-Jews in wartime Germany’s armed forces, and as intellectual forebears of National Socialism. Although Pravda no longer plays the leading role it did during the Soviet era, it remains an influential paper with a national readership. “It is difficult not to agree with the view of Russian historian Oleg Platonov,” writes Prussakov, who goes on to quote from Platonov’s Russkii Vestnik preface. “Obviously, it is time to put an end to the talk of the ‘special suffering of the Jewish people’,” concludes Prussakov.

How the public views the past, and especially 20th-century history, is a crucial aspect of the current struggle between “nationalists” and “internationalists” for the future of Russia. (See “Capitalism in the New Russia” in the May–June 1997 Journal.) In Russia, as in America and western Europe, “internationalists” promote a highly polemicized rendering of “Holocaust” history, with its guilt-ridden “lessons” for non-Jewish humanity, while “nationalists” have an interest in fostering a truthful and impartial perspective on this chapter of history.

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 16, no. 4 (July/August 1997), pp. 36f.

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a