The Noble Red Man

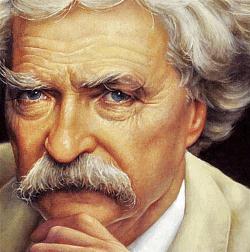

The tendency to idealize the Indian is hardly new in American history. Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens), a master debunker of cant and hokum, voiced his contempt for worshipful depictions of America’s aboriginal inhabitants in the following essay, which originally appeared in the September 1870 issue of The Galaxy.

In books he is tall and tawny, muscular, straight and of kingly presence; he has a beaked nose and an eagle eye.

His hair is glossy, and as black as the raven’s wing; out of its massed richness springs a sheaf of brilliant feathers; in his ears and nose are silver ornaments; on his arms and wrists and ankles are broad silver bands and bracelets; his buckskin hunting suit is gallantly fringed, and the belt and the moccasins wonderfully flowered with colored beads; and when, rainbowed with his war-paint, he stands at full height, with his crimson blanket wrapped about him, his quiver at his back, his bow and tomahawk projecting upward from his folded arms, and his eagle eye gazing at specks against the far horizon which even the paleface’s field-glass could scarcely reach, he is a being to fall down and worship.

His language is intensely figurative. He never speaks of the moon, but always of “the eye of the night;” nor of the wind as the wind, but as “the whisper of the Great Spirit;” and so forth and so on. His power of condensation is marvelous. In some publications he seldom says anything but “Waugh!” and this, with a page of explanation by the author, reveals a whole world of thought and wisdom that before lay concealed in that one little word.

He is noble. He is true and loyal; not even imminent death can shake his peerless faithfulness. His heart is a well-spring of truth, and of generous impulses, and of knightly magnanimity. With him, gratitude is religion; do him a kindness, and at the end of a lifetime he has not forgotten it. Eat of his bread, or offer him yours, and the bond of hospitality is sealed a bond which is forever inviolable with him.

He loves the dark-eyed daughter of the forest, the dusky maiden of faultless form and rich attire, the pride of the tribe, the all-beautiful. He talks to her in a low voice, at twilight of his deeds on the war-path and in the chase, and of the grand achievements of his ancestors; and she listens with downcast eyes, “while a richer hue mantles her dusky cheek.”

Such is the Noble Red Man in print. But out on the plains and in the mountains, not being on dress parade, not being gotten up to see company, he is under no obligation to be other than his natural self, and therefore:

He is little, and scrawny, and black, and dirty, and, judged by even the most charitable of our canons of human excellence, is thoroughly pitiful and contemptible. There is nothing in his eye or his nose that is attractive, and if there is anything in his hair that – however, that is a feature which will not bear too close examination … He wears no bracelets on his arms or ankles; his hunting suit is gallantly fringed, but not intentionally, when he does not wear his disgusting rabbitskin robe, his hunting suit consists wholly of the half of a horse blanket brought over in the Pinta or the Mayflower, and frayed out and fringed by inveterate use. He is not rich enough to possess a belt; he never owned a moccasin or wore a shoe in his life; and truly he is nothing but a poor, filthy, naked scurvy vagabond, whom to exterminate were a charity to the Creator’s worthier insects and reptiles which he oppresses.

Still, when contact with the white man has given to the Noble Son of the Forest certain cloudy impressions of civilization, and aspirations after a nobler life, he presently appears in public with one boot on and one shoe – shirtless, and wearing ripped and patched and buttonless pants which he holds up with his left hand – his execrable rabbitskin robe flowing from his shoulder an old hoop-skirt on, outside of it – a necklace of battered sardine-boxes and oyster-cans reposing on his bare breast – a venerable flint-lock musket in his right hand – a weather-beaten stove-pipe hat on, canted “gallusly” to starboard, and the lid off and hanging by a thread or two; and when he thus appears, and waits patiently around a saloon till he gets a chance to strike a “swell” attitude before a looking-glass, he is a good, fair, desirable subject for extermination if ever there was one.

Typical of the many “politically correct” motion pictures produced by Hollywood in recent years is “Pocahontas,” a 1995 Disney animated film that portrays Indians as liberated, nature-loving, wise and noble, and white Europeans as narrow-minded, ignorant, bigoted and greedy. In this scene from the movie, Pocahontas teaches English settler John Smith how to “paint with all the colors of the wind.” In reality, when the two first met in 1607, the Indian maiden was ten or eleven years old and, in keeping with local custom, bald and naked. Among the other “good Indian, bad white man” films produced in recent years have been “Dances With Wolves” with Kevin Costner (1990), “The Last of His Tribe” with Jon Voigt, and Robert Redford's “Incident at Ogalala.”

There is nothing figurative, or moonshiny, or sentimental about his language. It is very simple and unostentatious, and consists of plain, straightforward lies. His “wisdom” conferred upon an idiot would leave that idiot helpless indeed.

He is ignoble – base and treacherous, and hateful in every way. Not even imminent death can startle him into a spasm of virtue. The ruling trait of all savages is a greedy and consuming selfishness, and in our Noble Red Man it is found in its amplest development. His heart is a cesspool of falsehood, of treachery, and of low and devilish instincts. With him, gratitude is an unknown emotion; and when one does him a kindness, it is safest to keep the face toward him, lest the reward be an arrow in the back. To accept of a favor from him is to assume a debt which you can never repay to his satisfaction, though you bankrupt yourself trying. To give him a dinner when he is starving, is to precipitate the whole hungry tribe upon your hospitality, for he will go straight and fetch them, men, women, children, and dogs, and these they will huddle patiently around your door, or flatten their noses against your window, day after day, gazing beseechingly upon every mouthful you take, and unconsciously swallowing when you swallow! The scum of the earth!

And the Noble Son of the Plains becomes a mighty hunter in the due and proper season. That season is the summer, and the prey that a number of the tribes hunt is crickets and grasshoppers! The warriors, old men, women, and children, spread themselves abroad in the plain and drive the hopping creatures before them into a ring of fire. I could describe the feast that then follows, without missing a detail, if I thought the reader would stand it.

All history and honest observation will show that the Red Man is a skulking coward and a windy braggart, who strikes without warning – usually from an ambush or under cover of night, and nearly always bringing a force of about five or six to one against his enemy; kills helpless women and little children, and massacres the men in their beds; and then brags about it as long as he lives, and his son and his grandson and great-grandson after him glorify it among the “heroic deeds of their ancestors.” A regiment of Fenians will fill the whole world with the noise of it when they are getting ready invade Canada; but when the Red Man declares war, the first intimation his friend the white man whom he supped with at twilight has of it, is when the war-whoop rings in his ears and tomahawk sinks into his brain…

The Noble Red Man seldom goes prating loving foolishness to a splendidly caparisoned blushing maid at twilight. No; he trades a crippled horse, or a damaged musket, or a dog, or a gallon of grasshoppers, and an inefficient old mother for her, and makes her work like an abject slave all the rest of her life to compensate him for the outlay. He never works himself. She builds the habitation, when they use one (it consists in hanging half a dozen rags over the weather side of a sage-brush bush to roost under); gathers and brings home the fuel; takes care of the raw-boned pony when they possess such grandeur; she walks and carries her nursing cubs while he rides. She wears no clothing save the fragrant rabbit-skin robe which her great-grandmother before her wore, and all the “blushing” she does can be removed with soap and a towel, provided it is only four or five weeks old and not caked.

Such is the genuine Noble Aborigine. I did not get him from books, but from personal observation.

CODOH comments

Though there might be some truth to some of what Mark Twain says here, CODOH thinks that bashing Native Americans is not good style, and we do not endorse it. We post this article only due to our mission to post all papers published in this periodical, although we strongly disagree with this one. To balance this one-sided, unfair paper, The Journal of Historical Review later published a “Critical Response” to the unwise editorial decision of publishing Twain's diatribe, which we highly recommend you read as well: Zoltán Bruckner, “For a Balanced History of the American Indian”, The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 18, no. 2 (March/April), pp. 24-28

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 17, no. 3 (May/June 1998), pp. 12f.; reprinted from the periodical The Galaxy, September 1870.

Other contributors to this document:

Editor’s comments: n/a