Why President Truman Overrode State Department Warning on Palestine-Israel

Fifty Years Ago: A Fateful Admonition

Donald Neff is author of Fallen Pillars: US. Policy Toward Palestine and Israel since 1945, as well as of the 1988 Warriors trilogy. This essay is reprinted from the September-October 1994 issue of The Washington Report on Middle East Affairs (P.O. Box 53062, Washington, DC 20009).

On September 22, 1947, Loy Henderson strongly warned Secretary of State George C. Marshall that partition of Palestine into Arab and Jewish states was not workable and would lead to untold troubles in the future. Henderson was director of the US State Department's Office of Near Eastern and African Affairs, and his memorandum, coming less than a month after a United Nations special committee had recommended partition, stands as one of the most perceptive analyses of the perils that partition would bring.

Henderson informed Marshall that his views were shared by “nearly every member of the Foreign Service or of the department who has worked to any appreciable extent on Near Eastern problems.” Among the points Henderson made:[1]

- “The UNSCOP [UN Special Committee on Palestine] Majority Plan is not only unworkable; if adopted, it would guarantee that the Palestine problem would be permanent and still more complicated in the future.”

- “The proposals contained in the UNSCOP plan are not only not based on any principles of an international character, the maintenance of which would be in the interests of the United States, but they are in definite contravention to various principles laid down in the [United Nations] Charter as well as to principles on which American concepts of Government are based.”

- “These proposals, for instance, ignore such principles as self-determination and majority rule. They recognize the principle of a theocratic racial state and even go so far in several instances as to discriminate on grounds of religion and race against persons outside of Palestine. We have hitherto always held that in our foreign relations American citizens, regardless of race or religion, are entitled to uniform treatment. The stress on whether persons are Jews or non-Jews is certain to strengthen feelings among both Jews and Gentiles in the United States and elsewhere that Jewish citizens are not the same as other citizens.”

- “We are under no obligations to the Jews to set up a Jewish state. The Balfour Declaration and the Mandate provided not for a Jewish state, but for a Jewish national home.[2] Neither the United States nor the British Government has ever interpreted the term 'Jewish national home' to be a Jewish national state.”

Political Pressures

Although the State Department reflected Henderson's anti-partition views, Harry Truman's White House was supporting partition because of strong political pressures. President Truman was so unpopular at the time that there was speculation he might not be able to win the Democratic Party's nomination, much less the presidential race.[3] As the vote in the General Assembly on partition approached, Henderson made another effort to change Truman's mind. On November 24, he wrote that[4]

I feel it again to be my duty to point out that it seems to me and all the members of my Office acquainted with the Middle East that the policy which we are following in New York at the present time is contrary to the interests of the United States and will eventually involve us in international difficulties of so grave a character that the reaction throughout the world, as well as in this country, will be very strong.

He continued:

I wonder if the President realizes that the plan which we are supporting for Palestine leaves no force other than local law enforcement organizations for preserving order in Palestine. It is quite clear that there will be wide-scale violence in that country, on both the Jewish and Arab sides, with which the local authorities will not be able to cope…. It seems to me we ought to think twice before we support any plan which would result in American troops going to Palestine.

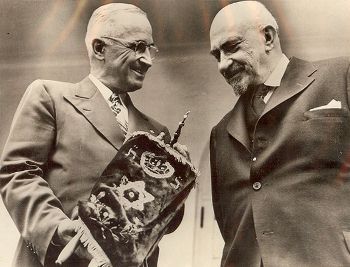

In his decision to support the new state of Israel, President Harry Truman put Jewish-Zionist interests ahead of American interests. Here Truman welcomes Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann to the White House, May 1948. Weizmann served as Israel's first president.

Under Secretary of State Robert A. Lovett was so impressed with the memo that he personally read it to President Truman. But Truman, worried about his election campaign in the coming year and urged by advisers such as Clark Clifford to endorse partition as a way to gain Jewish support, ignored Henderson's warnings.[5] Five days later the United States voted for partition in the historic session of the UN General Assembly.

Major Responsibilities

As the months passed and Palestine descended into the chaos and violence predicted by Henderson and the State Department, Truman could no longer escape the fact that partition had led to massive bloodshed. George Kennan, the director of policy planning at the State Department, warned on February 24, 1948, that violence in Palestine could only be stopped by the introduction of foreign troops. He urged that the US not be drawn into the quagmire:[6]

The pressures to which this Government is now subjected are ones which impel us toward a position where we would shoulder major responsibility for the maintenance, and even the expansion, of a Jewish state in Palestine …. If we do not effect a fairly radical reversal of the trend of our policy to date, we will end up either in the position of being ourselves militarily responsible for the protection of the Jewish population in Palestine against the declared hostility of the Arab world, or of sharing that responsibility with the Russians and thus assisting at their installation as one of the military powers of the area.

Similar views were expressed by the CIA and the Defense Department.

Despite such grave concerns, Clifford continued to urge Truman to maintain support of partition. In a memo on March 6, Clifford argued that if the US deserted it now it would make “… the United States appear in the ridiculous role of trembling before threats of a few nomadic desert tribes…. the Arabs need us more than we need them. They must have oil royalties or go bankrupt.”[7]

Implicit was the underlying message that Jews were more important to Truman's election than Arabs. As Truman himself once said: “I'm sorry, gentlemen, but I have to answer to hundreds of thousands who are anxious for the success of Zionism. I do not have hundreds of thousands of Arabs among my constituents.”[8]

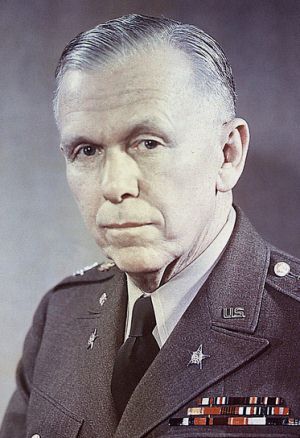

Secretary of State George C. Marshall emphatically opposed President Truman's decision to give official US recognition to Israel, which he believed was motivated by partisan eagerness for Jewish backing in the November 1948 presidential election.

By now, Arabs and Jews were slaughtering each other on a daily basis. Jewish forces were gathering strength and were on the verge of major attacks outside the limits defined by the UN for the Jewish state. Tens of thousands of Palestinians had already been turned into refugees, presaging the tragedy that soon would result in more than half of the total Palestinian community losing their homes.

The horrors unfolding in Palestine could not be ignored. On March 19, Truman renounced partition. The US announced in the UN Security Council that America believed partition was unworkable and that a UN trusteeship should be established to replace the British when they ended their withdrawal from Palestine on May 14.[9]

Reaction in the press and the Jewish community was deafening. Headlines screamed: “Ineptitude,” “Weakness,” “Vacillating,” “Loss of American Prestige.”[10] From Jerusalein, the American consul general reported: “Jewish reaction … one of consternation, disillusion, despair and determination. Most feel United States has betrayed Jews in interests Middle Eastern oil and for fear Russian designs.”[11] Truman tried to shift the blame to the State Department, claiming it had acted without his approval. However, it is clear that he had personally given approval for the change in strategy.[12]

In the end, Truman regained Jewish support two months later when he overrode stiff opposition by the State Department and made the United States the first nation to recognize Israel as an independent nation on May 14. Truman's decision had so disgusted Secretary of State Marshall that he told Truman to his face that he believed the president was acting on Clifford's political calculations to win Jewish support, adding: “I said bluntly that if the President were to follow Mr. Clifford's advice and if in the elections I were to vote, I would vote against the President.”[13]

On November 2, Truman defeated Thomas E. Dewey to win election to a full term as president.

Notes

| [1] | US Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1947 (vol. 5), The Near East and Africa (Washington, DC: US Govt. Printing Office, 1971), “The Director of the Office of Near Eastern and African Affairs (Henderson) to the Secretary of State,” September 22,1947. Text is also in Evan M. Wilson, Decision on Palestine: How the US. Came to Recognize Israel (Stanford, Calif: Hoover Institution Press, 1979), pp. 117-21. |

| [2] | The Balfour Declaration was issued November 2, 1917, saying Britain favored establishment of a “national home” for Jews in Palestine. Its text: “His Majesty's Government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.” Text of the early and the final drafts of the declaration are in Thomas Mallison and Sally V , The Palestine Problem in International Law and World Order (London: Longman, 1986), pp. 427-9. Text of the Mandate is inWalter Laqueur and Barry Rubin (eds.),The Israel-Arab Reader (New York: Penguin, 1987 [revised and updated]), pp. 34-42; a partial text appears in Fred J. Khouri, The Arab-lsraeli Dilemma (Syracuse University Press, third edition, 1985), pp. 527-28. |

| [3] | Steven L. Rearden, History of the Office of the Secretary of Defense: The Formative Years, 1947-1950 (Washington, DC: Historical Office, Office of the Secretary of Defense, 1984), p. 181. |

| [4] | US Dept. of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1947 (vol. 5 [1971]), “Memorandum by the Director of the Office of Near Eastern and African Affairs (Henderson) to the Under Secretary of State (Lovett),” November 24, 1947, pp. 1281-82. |

| [5] | Evan Wilson, Decision on Palestine (1979), p. 124. |

| [6] | US Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1948 (vol. 5), The Near East, South Asia, and Africa (Washington, DC: US Govt. Printing Office, 1975), “Report by the Policy Planning Staff,” Feb. 24, 1948,pp.656-57. |

| [7] | US Dept. of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1948 (vol. 5 [1975]), “Memorandum by the President's Special Counsel (Clifford),” March 6, 1948, pp. 687-96. |

| [8] | Robert J. Donovan, Conflict and Crisis: The Presidency of Harry S. Truman, 1945-1948 (New York: W.W. Norton, 1977), p. 322. |

| [9] | Thomas J. Hamilton, New York Times, March 20, 1948; the text of the US statement is in the same edition, as well as in US Dept. of State,Foreign Relations of the United States, 1948 (vol. 5 [1975]), “Statement Made by the United States Representative at the United Nations (Austin) Before the Security Council on March 19, 1948,” pp. 742-4. |

| [10] | Peter Grose, Israel in the Mind of America (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1983), pp. 275-76. |

| [11] | US Dept. of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1948 (vol. 5 [1975]), “The Consul General at Jerusalem (Macatee) to the Secretary of State,” March 22, 1948, p. 753. |

| [12] | Donald Neff, “Palestine, Truman and America's Strategic Balance,” American-ArabAffairs, Summer 1988. |

| [13] | US Dept. of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1948 (vol. 5 [1975]), “Memorandum of Conversation, Secretary of State,” May 12. 1948, pp. 975-6. |

A Preference for Equality

“The human heart also nourishes a debased taste for equality, which leads the weak to want to drag the strong down to their level, and which induces men to prefer equality in servitude to inequality in freedom.”

—Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America (1835-1840)

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 16, no. 5 (September/October 1997), pp. 13-15; reprinted from The Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, September-October 1994.

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a