A Postcard from Auschwitz

The following is a true account of my personal visit to the camp. All photos are my own.

Krakow is a beautiful city in early summer, the stand-out among southern Polish cities. Miraculously, the old city center survived both world wars unscathed. The huge central square is a sight to behold, and with no less than three major universities, Krakow bristles with youthful energy. Coming down by train from Warsaw, I was able to arrange a two-night stay before continuing on my way to Vienna. As with most major European cities, one quickly learns of the “must-see” sites: St. Mary’s Basilica, Wawel Castle, the salt mines, and of course, Auschwitz.

By Thomas Dalton

By Thomas Dalton

By Thomas Dalton

By Thomas Dalton

By Thomas Dalton

By Thomas Dalton

By Thomas Dalton

By Thomas Dalton

By Thomas Dalton

By Thomas Dalton

By Thomas Dalton

By Thomas Dalton

By Thomas Dalton

By Thomas Dalton

By Thomas Dalton

By Thomas Dalton

By Thomas Dalton

By Thomas Dalton

In the background of Photo 4 is Block 24, the building that housed the brothel and library for (non-Jewish) inmates; the main entrance is shown in Photo 5. Photo 6 shows a typical view in the camp, of barrack buildings and a guard tower.

This being my first visit to Auschwitz, I decided to see it as a tourist would. This was not only easier (I was travelling alone), but allowed me to better understand the “official” portrayal of the camp and of events there. Auschwitz is the number one tourist destination in all of Poland; about 1.3 million visit the camp every year—coincidentally, about the same number as is alleged to have been killed there. The official guided tours dictate a particular image of the camp, and I was as interested in this image as the camp itself. I wanted to see what the public sees.

So I went to one of the many tourist information offices around town and purchased a standard “day trip” to Auschwitz. The package, which included free pickup and return delivery to my hotel, cost 90 złoty, about $30—quite a deal. My pick-up time was set (8:30 am), and the van would be at my hotel the next morning, for the “6-hour tour.” Plenty of time to see the place, I thought, given that Oswieçim—the Polish name of Auschwitz—was only some 70 kilometers (about 40 miles) from Krakow.

The van dutifully arrived the next morning. But I soon realized that, as at Auschwitz itself, the tour was not quite as expected. The vehicle—a bit larger than I anticipated, more like a small bus—had a capacity of about 25 people. I was one of the first in, and the driver proceeded to cover much of the city in order to pick up our remaining guests. But between rush hour traffic, construction delays, and people slow getting out to the bus, a good hour went by before we were even ready to depart Krakow. So, my “6-hour tour” was now down to five. And, of course, it would require another hour or so to return everyone; in other words, I was really getting a “4-hour tour.” Not sure that that counts as a “day trip,” but such is the life of a tourist in Poland. (I’m no tour planner, but it seemed to me that, if everyone simply walked to the central tourist office and met the bus there, that we could have saved a couple hours…)

It turned out that this little time crunch would impact our tour itself, and, in my suspicious mind, served an ulterior purpose. But I come to that matter in due course.

There are three distinct and roughly parallel paths from Krakow to Oswieçim: the (longer) expressway route, and two cross-country routes via two-lane roads. In good traffic, as I learned, all three take about one hour—a rather long time for a mere 40 miles. But Poland has only two kinds of roads: expressways and two-lane roads, and the latter are painfully slow. Our driver opted for one of the scenic country rides.

As soon as we were clear of Krakow city, the driver pulled out a DVD and popped it into a dashboard player. A small screen above us lit up: this was our complimentary 20-minute documentary about the camp (in English). No surprises here. We were treated to the usual recounting of the “extermination camp” history, the appalling conditions, the emaciated inmates, the gas chambers, and the “over one million” Jewish deaths. Horror awaits, it seemed to say.

The remainder of the trip was uneventful. The forecasts called for rain that day, but supposedly not until later in the day; with luck it would hold out for our visit. Around 10:30 am—a good two hours after my pickup—we rolled into the town of Oswieçim. It was a typical smallish European town, nicely maintained, with the usual amenities. We drove only a few minutes through the town when, suddenly, we arrived at the Main Camp, Auschwitz I. For those not familiar, “Auschwitz” is comprised of three primary facilities, and dozens of smaller sub-camps. The original and Main Camp is Auschwitz I, also called the Stammlager. It opened as a Nazi camp in 1940, but was originally built by the Polish army as a military barracks complex, apparently during World War I. This camp allegedly had a single gas chamber, which we were about to see. But the vast majority of the gassings are said to have occurred at Auschwitz II, known as Birkenau. This would come later in the day. The third facility, Auschwitz III (Monowitz), was located some three kilometers from the town, and served as an industrial facility; no mass murder is alleged to have happened there, and consequently it receives few tourists.

Knowing all this, I was still surprised at how integrated the Main Camp was into the town. This, I think, is not the usual image we have: the dreaded “Auschwitz death camp” located in the heart of a civilian village. But we have a good explanation for this, of course. Its original function, as a Polish military camp, had nothing to hide. And even as a German camp, when constructed in 1939 and 1940, it was not originally intended, even on the traditional view, as an extermination camp. The Germans were simply making good use of a captured military barracks.

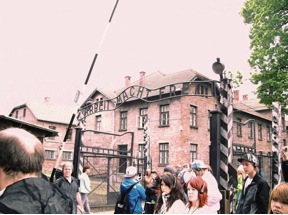

Pulling into the parking lot, we were immediately confronted with a mass of vehicles: passenger cars, taxis, tour buses like our own, and full size long-haul buses packed with people. The place was a frenzy of activity—see Photos 1 and 2. Our bus disembarked, we merged with another small group, and then were assigned a tour guide: a cheerful young woman with a good knowledge of English, and of the standard story she was scripted to present.

We pushed through the mob into the entrance building, past the gift shop, and on into a small alcove. There we were given our headsets and radio receivers. It is a rather high-tech affair: with all the commotion and simultaneous tours in multiple languages, the Poles gave the tour guide a radio voice transmitter; each of us could then hear her speaking through our headsets. Thus, each group heard only their personal guide. On the one hand, this was a clever and useful solution. No confusing cross-talk, and even if you drifted away from the group, you could still hear your guide speaking loud and clear. On the other hand, it had a noticeable (and to me, suspicious) side effect: questions from individuals to the guide could not be heard by the group. They were necessarily individual questions between you and the guide. When I did this on a couple of occasions, she answered me personally, but shut off the transmitter. No one else in the group heard either my questions, or the answers. Very clever, I thought to myself.

Moving into the camp grounds, we immediately came upon the famous “Arbeit Macht Frei” sign—“Work Makes You Free” (Photos 3 and 4).

Our group wandered through the camp, following the guide as she made stops in various barracks to tell us stories of the appalling conditions faced by the inmates. The buildings were mostly empty. Some contained walls of inmate photos; others, simulated sleeping bunks. One final barrack was set up rather as a standard museum. It had exhibits displaying inmate suitcases, personal items, and hair (cut from inmates as a precaution against lice). One large glassed-in exhibit showed an apparent mound of “thousands” of shoes—though, as Germar Rudolf has noted, the mound is displayed on an unseen elevated board, which is empty beneath. This is the same trick that grocers use to display fruit, to give the illusion of a vast quantity. The mound was not so vast after all.

At one point the guide mentioned the total Auschwitz death count as roughly 1 million Jews and thousands of others. I caught up to her and asked if the toll wasn’t previously claimed to be 4 million. (Microphone off.) Yes, she said, but better research in the 1980s and 1990s had confirmed the new, lower figure. Any chance it would be lowered still in the future?, I asked. Unlikely, she said.

By this time, people were beginning to talk among themselves about the as-yet-unseen gas chambers. The guide then reminded us that, indeed, we were about to come to the gas chamber itself. “And oh, by the way,” she added, “most of the gassings were at Birkenau. But we’ll see that later.” It was already approaching 12:00 noon.

Finally, we arrived at “the” gas chamber in the Main Camp, also called Krematorium #1 (or Krema 1, for short). It was a partially underground structure with a flat roof and sloping, grassy side walls with large trees—see Photo 7. Few statistics were given on the details of the gassings: no start or finish date (in fact, February to November 1942), no details on the gassing procedure (Zyklon pellets thrown in through roof vents), and only rough numbers of Jews allegedly gassed there (about 20,000—a mere two percent of the claimed Auschwitz toll). We could not enter via the “inmate entrance,” as this was blocked off (Photo 8), so we went around to the other side (Photo 9).

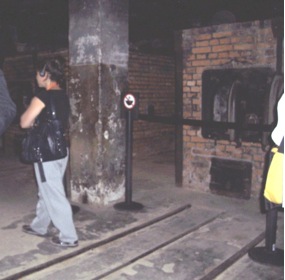

Upon entering the building, we were treated to what must have been the world’s shortest tour of a gas chamber. We walked in, took a hard right turn into a small room, then a hard left into the gas chamber itself. It was a windowless, rectangular room, about 25 x 5 meters. The guide said little more than “this is the gas chamber, no photos please,” and then she was off into the adjoining room with the cremation ovens. Rebel that I am, and not wanting to miss an opportunity, I lagged behind the group and then snapped a quick photo (#10). But the guide was gone—no chance to ask about the many post-war modifications to the room (chamber size, door location, chimney), nor about its history as a morgue and an air raid shelter. No chance to ask how 800 to 1000 people were jammed into that room, nor how the deadly Zyklon pellets were collected up without killing the guards handling the dead bodies. No chance to ask why the four Zyklon vents appeared to be added later than the original construction. No chance to ask about French traditionalist Eric Conan’s claim that “everything there is false.”

In the oven room (Photo 11), we had about one minute to view the ovens themselves—“no photos please”—and our guide was off. No chance to ask why the reconstructed chimney was not attached to the ovens. No chance to ask why the six cremation muffles, which could handle six bodies per hour, were such a capacity mismatch with a gas chamber that could kill 800 to 1000 at a shot. Note: it would have taken roughly 150 hours—or more than 6 days working round the clock—to dispose of all the bodies from a single gassing.

Outside again, our guide was suddenly much more relaxed. Now we have time for a break, for bathrooms, for a visit to the gift shop, she said. “Be out front at the bus at 12:30, for the ride over to Birkenau.” Finally, I thought—the highlight of the trip.

Again, the “ride to Birkenau” was surprising—all of about five minutes. Out of the small village, across a field, and there we were, at the famous entrance building, complete with train tunnel (Photo 12—a poor exposure, as my camera was beginning to fail me). There we were, at the site of the greatest mass killing in human history: 1.1 million people, the vast majority Jews, killed over two years (1943 and 1944), 90 percent of whom were gassed in the four crematoria.

I was very anxious to get inside and look around. Then another surprise. “Because we are running late,” said our guide (“late”?), “we will only have time to see the main guard tower and one of the barracks. Unfortunately, we won’t be able to see the gas chambers.” What?! You must be kidding me, lady! No gas chambers?! Like hell!, I said to myself. “How much time do we have until the bus leaves?,” I asked our guide. “About 25 minutes.” “I’m going to the gas chambers.” “Ok,” she said as she headed off with the group. I didn’t care if I had to walk back to Krakow; I was going to see the Birkenau gas chambers.

Inside the main gate, one sees the train tracks going out into the distance, to a dead end, and flanked by guard towers and a loading area (Photo 13). Being familiar with the camp layout, I knew that the main objectives were Kremas 2 and 3, and that they were straight ahead of me, at the end of the tracks, about 800 meters—almost half a mile—away. Quick calculation: I can walk there in 10 minutes, and 10 minutes back, leaving 5 minutes for the chambers—or I can run. I ran.

So, after an earnest five-minute run, I could at last see the ruins of the infamous Krema 2—site of the single greatest death toll at Auschwitz: some 300,000 people, on the conventional view (Photo 14). Across the way, its twin facility, Krema 3—site of another 275,000 gassings (Photo 15). Both buildings were destroyed by the Germans upon abandoning the camp, though Krema 2 retains some very relevant and important structures.

Standing there in front of the remains of both buildings, one gets a real sense of the improbability of the conventional story. Each building had an almost completely underground chamber, roughly 30 x 7 meters, at right angles to the main building, which contained the cremation ovens. On the revisionist view, this chamber was a morgue—a large, unventilated, but cool, place to store dead bodies (many infectious) until they could be cremated. On the standard view, this room was the gas chamber—a place in which 2,000 people were collectively gassed in less than 20 minutes. Photo 16 shows the collapsed roof of the Krema 2 chamber as it exists today.

Now, imagine this: You are somehow able to pack 2,000 frightened, sick, angry people, wall to wall, into this underground room—a room with only a single narrow doorway from the main building. You then kill them all by sprinkling pellets of Zyklon-B over their heads, through openings in the roof. Now you have to quickly extract the dead bodies, steeped in poisonous gas, without killing yourself or your fellow workers. No problem—if you could peel the roof off and scoop them out with a backhoe. Lacking that option, it would be nearly impossible in any reasonable amount of time. And yet the experts, like Franciszek Piper, claim that it took only three or four hours. Incredible—that they can make such claims, and no one (except the few revisionists) challenges them.

There are other stories in these remains. One is the search for residue of the deadly cyanide gas. If the chambers were used on as many people as claimed, the remaining bricks should have detectable cyanide compounds still in them. And yet none are to be found. Another story is the search for the roof openings into which the Zyklon pellets were poured—supposedly four per chamber. Krema 2’s roof is sufficiently intact that we should be able to find evidence of these holes. And yet they are not to be found—not one single indisputable hole.

But my time was running short. A quick dash over to Krema 3 for a last shot or two (Photo 17), and then back to the bus. The other two crematoria, Kremas 4 and 5, were across the camp, a good 600 meters away, in the wrong direction; they would have to wait for my next visit. So too would the two “bunkers,” or small converted farmhouses, that were allegedly used to pilot the Birkenau gassing project in 1942. Almost nothing remains of them, yet it would be interesting to hunt down their locations—the sites of some 250,000 Jewish gassings, it is said. But now it’s time to go. Heading back along the tracks toward that most infamous of buildings, I couldn’t resist pausing for one more shot (Photo 18).

I arrived back at the bus just as the crowd was loading up—perfect timing. After an hour ride we returned to Krakow around 2:00 pm. But rather than sitting it out for another hour circuit of the city as we returned my fellow riders, I opted to hop out at the first stop and walk home. A good move. I was back at my hotel for less than an hour when the skies unleashed a pounding rain. So luck was with me after all, that day—my day in Auschwitz.

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 4(2) (2012)

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a