Aspects of the Tesch Trial

“I do not feel guilty. I did my duty working from morning ’til night for my country, just as the English would work for their country.” —Bruno Tesch, interrogation of September 26, 1945

“It is an official duty of humanity to exterminate vermin.” —Bruno Tesch, interrogation of September 26, 1945

In March 1946, Bruno Tesch, the head of the firm Tesch & Stabenow (often abbreviated as TESTA), was put on trial along with his Prokurist Karl Weinbacher and the gassing (i.e. fumigation) technician Joachim Drosihn, on the charge that they “did supply poison gas used for the extermination of allied nationals interned in concentration camps well knowing that the said gas was to be so used.”[1] Tesch had been brought to the attention of British authorities by former employee Emil Sehm, who had claimed that while working at the company he had seen a travel report in which Tesch had agreed to provide technical assistance with exterminating the Jews with poison gas. After seven days of proceedings, Tesch and Weinbacher were convicted and sentenced to death, while Drosihn was acquitted.

The trial received early revisionist attention from chemist William Lindsey, who wrote a substantial (if somewhat intemperate) 1983 article outlining its course,[2] and has also been criticized from the orthodox side, notably by Jean-Claude Pressac, who wrote that “In 1946, simple malicious gossip could easily lead to someone being hung. I do not know whether the ‘trip report’ was produced before the Tribunal,[3] but if it was not then, this trial was a masquerade.”[4] In the only significant orthodox account of the trial, Angelika Ebbinghaus focuses on background information, offering little on the details of the trial.[5] Some aspects of the trial have also been covered in a history of Tesch & Stabenow.[6]

For their information on the Tesch case, the works cited above relied almost exclusively on the trial transcript. This paper aims to deepen understanding of the trial through the materials available in the investigation files. These files offer insight into both the specific case against Tesch, as well as the conduct of postwar investigations in general. An additional benefit is that the investigation files contain a number of sources of independent interest. This paper will not address the witnesses concerning homicidal gassings who appeared at the trial (notably C.S. Bendel and Pery Broad), first, because they are better considered in a broader context, and second, because their statements have already been discussed in the revisionist literature. We are not aiming at a treatment of all aspects of the trial, and will be content to pass over topics we consider unenlightening or which have already been adequately covered by other authors. Though in principle self-contained, this paper is not structured as an introduction to the Tesch trial, and the reader may find it useful to first familiarize himself with the case by reading Lindsey’s article. The published summary of the case[7] may also serve as a useful introduction. When quoting from the investigation materials, we have always used the original English translation when one was available, while sometimes noting discrepancies from the original German. Where there was no original English version, the translation is the author’s.

1. The Investigation

The investigation of Bruno Tesch and TESTA began with a letter from the former TESTA bookkeeper Emil Sehm to British authorities on June 29, 1945. Sehm wrote:[8]

“According to my estimation I am able to supply very important information that means fresh evidence to commit war criminals for trial. The war crime I am referring to concerns an official discussion which took place between a businessman of an IG Farben sister concern with leading men of the OKW [Army High Command], about the application of the hydrocyanic acid process to kill human beings. Further the training of SS men to apply this process.

My profession gave me the opportunity to see top secret files and that is where my knowledge results from.”

As his first letter received no response, Sehm sent another letter on August 24. He wrote:[10]

“In my capacity as accountant and later in special cases dealing with the correspondence I got acquainted with a few top-secret documents. When dealing with a particular file, I was instructed by Dr. TESCH about the secrecy which had to be kept about this particular file. The contents of this file was a report and I can very well remember it. It had the meaning as follows:

Dr. TESCH reported about an invitation he received to a conference at the OKW BERLIN. He stated to which members he was introduced and in which way and form. About the subject of the conference he wrote that the speaker explained that the execution of the Jews by shooting has developed in a mass execution and furthermore it is very unhygienic. Dr. TESCH was asked to submit any suggestion, whether and how Jews could be exterminated by using hydrocyanic acid. Afterwards technical points about the application of hydrocyanic acid were discussed and amongst other suggestions one way was suggested that all Jews detailed for extermination should be taken into a barracks previously prepared (gas-tight). During the night a trained man (using a respirator) should enter the barracks and place hydrocyanic acid plates in the rooms. In future, instead of getting buried, dead bodies will be cremated. Dr. TESCH offered himself to SS men who will be selected by the OKW and put at his disposal to train on courses for this purpose (using hydrocyanic acid).

In fact there were some SS men trained by him and his fellow worker. The book-keeping disclosed further that the firm has supplied hydrocyanic acid called ‘T’ Gas[9] to the OKW and SS offices (Dienststellen).

I copied this report and showed it to one of my reliable friends. Later I told it as well to Herr Frahm, Lorenzenstrasse 10. This copy was burnt immediately as I realized that it would have been useless to take any further steps for the time being to stop the crime. […]

On this conference according to the report of Dr. TESCH no high ranking SS were present, but the highest authorities of the OKW were leading this discussion. […]

As an economical adviser, I was convinced from the beginning that NSDAP means only war and destruction of the economy and it gives me a satisfaction to write this statement.

Through the knowledge of all these happenings my eyes were opened and I was fully convinced that the German nation has criminals as leaders and it will be the tragedy of the German people to be made responsible for the crimes inflicted on the human race.”

To recapitulate: Sehm claimed to have seen one of Tesch’s travel reports in which it was specified that (1) the method of killing Jews and disposing of their corpses was to be switched from shooting+burial to HCN+cremation, (2) the reason for this transition was hygiene, (3) the planning for gassing Jews was handled by the OKW, and (4) the killing with HCN was to take place by having a gassing technician enter the barracks in which Jews resided during the night, when the Jews would presumably be asleep, and carry out a disinfestation. This gassing method is so absurd that it is difficult to believe that Sehm was taken seriously – but he was. That September, British investigators visited TESTA with Sehm in tow and arrested Tesch. The date of the visit is a little uncertain. The investigative team’s report on the case says that it took place “on or about the 18th September 1945.”[11] Authors relying on the trial transcript have stated that Tesch was arrested on September 3,[12] as the prosecutor Gerald Draper stated in his introductory speech.[13] However, the dates of September 19 and September 12 were also given during the trial.[14]. As the arrest is described in a statement dated September 18, the date of the 19th would at least seem to be excluded. In the aforementioned statement, Sehm wrote that “the filing room in which I believed the file which would incriminate Dr. Tesch to be, was burned out […] during Mar 1944, after an air attack”. He detailed his confrontation with Dr. Tesch:[16]

“I stated to him: I have knowledge of a Traveling Report compiled by you. According to this you have negotiated with leading persons of the OKW. It was submitted to you that the shooting of Jews had increased to such an extent that this could no longer be justified from the hygienic point of view. It was proposed to employ the prussic acid process for the ‘liquidation’ of the Jews. You were asked for your opinion in the matter. Furthermore, the single phases of the operation were explained in the report.

Interrupting my statement, Dr. Tesch said that I[15] knew perfectly well that the firm was only carrying out gassing of vermin, etc; only after being repeatedly questioned did he deny to know of such a Travel Report. The female stenographers, Miss Radtke and Miss Knickrehm were also questioned as to whether they could remember that this Travel Report was dictated to them by Dr. Tesch. Both denied it.”

In his statement of October 10, Sehm stated that these events took place on September 18.[17]

Tesch was interrogated by Captain Gerald Draper and Captain Frank on September 26. The interrogation is available only in English. He was told that five million people had been gassed at Auschwitz, and replied that this was news to him – he had first heard of homicidal gassings in the press and radio. He did not believe that the gas he had supplied had been used for mass killing. He saw little sense in the description he was given of fake showers being used as gas chambers, and absolutely denied Sehm’s story about the travel report. While in many cases he was deferential to the interrogators on matters outside his direct experience (“If you say so, gentlemen, perhaps it is true; you may have better evidence”), he was very definite about the travel report (“It does not exist”). Sehm, he said, had always been a “book of seven seals” to him, and may have borne a grudge against him because of their past differences regarding pay and because of Sehm’s dismissal from the firm.[18] The interrogators, however, told him that Sehm’s statement could be confirmed, because Sehm’s friend Frahm (mentioned in Sehm’s letter of August 24) had also seen the travel report:[19]

“Q. In a secret file there was a report about an invitation to a conference in Berlin, was there not?

A. The only invitation received was to a conference with the Army and SS, the Reichs Ministry of Food and the Reichs Ministry of Interior.

Q. It is useless for you to say that is not so, as Sehm has seen the file. Is it possible there were files in the offices which were so secret that they could be seen by Sehm and not by you?

A. It is possible.

Q. And you are the head of the business?

A. I was away for more than half the year. I was away often, and whilst I was away secret papers arrived.

Q. Do you remember going to a very big conference in Berlin, with many high-ups?

A. No, I cannot recollect.

Q. Is it possible?

A. No, I do not think so. I did participate in conferences with the Reichs Ministry of Food and representatives from the three Services were present, but not high-ups.

Q. What were the ranks of the senior members?

A. Senior Staff Medical Officers.

Q. Do you remember a conference at which they talked about methods of doing away with the Jews?

A. No.

Q. Is it not unfortunate that Sehm read about it in one of your files?

A. I cannot imagine what he read.

Q. But someone else also saw the file – Frahm?

A. I have not met him.

Q. He is a friend of Sehm, and he also saw the file?

A. I do not understand, I cannot understand how a stranger could see a business file.

Q. Because Sehm showed him it.

A. I cannot credit Sehm with such a breach of confidence. He was not entitled to show such things to strangers, but if he did so he must have known what he was doing. I have absolutely no recollections of what Sehm could be thinking about.

Q. Sehm extracted the report from the file and showed the report from the file to his friend Frahm. It is easy to find out whether Sehm is lying, because we can ask Frahm.”

Indeed, one could and did ask Frahm. Two weeks later, Frahm gave a statement. Unfortunately for the investigators, Frahm did not confirm that Sehm had shown him such a document. Rather, Frahm stated that Sehm had shown him the letter he had written to the British in the summer of 1945:[20]

“I have not worked for the firm of TESCH and STABENOW but a friend of mine, Herr Emil SEHM, worked for this firm as bookkeeper. He told me one night that he did not want to work for TESCH and STABENOW any more but he did not tell me why.

One day in July or August 1945 Emil SEHM told me the following: ‘Now I can tell you why I wanted to leave the firm of TESCH and STABENOW.’ He showed me a letter that he had written to the British Military Authorities. It said that Dr TESCH had been in BERLIN with the Commander of the Wehrmacht and Dr TESCH had been told by the Commander of the WEHRMACHT that he or a member of his firm would have to instruct 30 SS men in how to use BLAUSAUERE-GAS [sic]. These SS men, when they had been instructed in the use of this gas, had to wear gas masks and go into the barrack rooms in the concentration camps and put tablets of the gas in the corners of the room and go out and shut the door.

Emil SEHM also told me that he had seen in a file in Dr TESCH’s office that the Ober-Commander of the Wehrmacht told Dr TESCH to instruct the 30 SS men in the use of BLAUSAUERE-GAS [sic].”

Frank and Draper’s seeming belief that Frahm had seen the file is inexplicable in terms of the available documents. The reader may verify that in the passages quoted above, Sehm did not make this claim. There are several possibilities for explaining this: Frank and Draper may have been lying in order to intimidate Tesch, they may have misunderstood the documents, Sehm may have verbally told them something along these lines which was not put down in writing, or the available versions of Sehm’s early statements may have been altered in order to remove contradictions from the prosecution’s narrative. In light of the numerous cases of dishonesty on the part of the investigative team which will be proved below, the last possibility cannot be dismissed out of hand, given that the available versions are not originals, but copies in English translation. That said, there is nothing to prove that this was the case.

Emil Sehm also gave a statement on October 10. He explained that he had found the alleged travel report filed under “Wehrmacht”, and that it was not marked as secret or confidential. He then quoted from the alleged travel report as follows:[21]

“Mr. ……… (Name of the Wehrmacht representative missing) explained to me that the shooting of Jews became a Mass Shooting and it proved to be unhygienic. He thought this could be improved by gassing the Jews with BLAUSÄUREGAS and burn the corpses afterwards. He asked me to supply him with suitable propositions. I suggested to carry out the extermination of the Jews by the usual method of gassing. After they have been put into the Barracks (the Jews) which were made airtight, a BLAUSÄURE expert proceeds to the rooms at night for the purpose of laying BLAUSÄUREGAS tablets. The corpses could be disposed of in the morning.”

In case his previous statements had left any doubt in the matter, he reiterated that “With regard to the travel report I want to mention again that according to the report the negotiations were not carried out by the higher SS leaders but with the leading personalities of the Army High Command.”

While Sehm’s statement did not say that he showed the documents to Frahm, as the British interrogators claimed, it did state that he had told Frahm about his reason for leaving TESTA. In denying that Sehm had told him this (“he did not tell me why”), and claiming that Sehm had said after the war that he was finally able to inform him of this reason (“Emil SEHM told me the following: ‘Now I can tell you why I wanted to leave the firm’ ”), Frahm directly contradicted Sehm’s assertions.

Had Frahm’s statement been taken earlier, and had the investigators been more clearheaded, that might have been the end of the case. But by October 10, the case could no longer be easily stopped. On September 28, the firm had been visited again. The report on this visit written by Sergeant D. Ellwood complained that Weinbacher “could not or would not give all the information sought.” Ellwood spoke to two gassing technicians, Marczinkowski[22] and Pietsch[23]:[24]

“Both stated that they knew nothing about Gas Chambers, but had been engaged in “delousing” only. It is practically certain that they had been “briefed” in what they should say when questioned, as they both professed ignorance of the simplest things. It was only after having been spoken to sharply that the above was wormed out of them.”

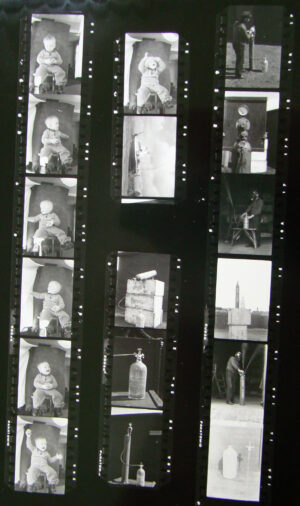

Ellwood’s report was forwarded along with a note that underscored how the investigators sought to interpret normal delousing facilities as homicidal:[25]

“It will be noticed that the ‘delousing’ apparatus referred to is in fact a gas chamber installation as pictured in the pamphlet herewith entitled ‘Die kleine TESTA-FIBEL über Normal-Gaskammern’. These chambers [10 cubic meter delousing chambers. –FJ] are certainly large enough to have been used for the purpose of annihilation of human beings. […]

The firm has asked if they can have the enclosed file back!”

On October 2nd, after reading Ellwood’s report, Tesch’s interrogation, and a report (presumably Sehm’s) on the confrontation between Sehm and Tesch,[26] Group Captain A.G. Somerhough wrote that he was “by no means satisfied that [Tesch] was not well aware of the purposes for which he was supplying this cyanide and that he did not only act as a technical advisor on the question of its use for the purpose of exterminating human beings.”[27] Because of Tesch’s connection to Sachsenhausen, Somerhough suggested handing him over to the Russians for interrogation “if they think they can get any more out of him, bearing in mind that they are in possession of some actual lethal chamber apparatus”,[28] proposed “to turn a War Crimes Investigation Team on to this case”,[29] and suggested that Tesch, Weinbacher, Drosihn, and twelve TESTA gassing technicians be arrested.[30]

In the meantime, Tesch had been released. Like so many things about the investigation, the date of his release is uncertain. The investigative team stated that it took place on October 1st,[31] a claim which was repeated at the trial.[32] The same date was also claimed by A.W. Freud[33] during his interrogation of Drosihn, but the latter remembered that Tesch returned on a Saturday,[34] which would necessarily have been Saturday September 29.

Once on the case, War Crimes Investigation Team [WCIT] Number 2 carried out arrests on a scale even broader than intended by Somerhough, rounding up and arresting all available employees of TESTA, secretaries and accountants along with gassing technicians. Weinbacher was arrested on October 6th, and Tesch and Drosihn the next day.[35] According to the investigative team’s report, nine employees were arrested on the 6th, three on the 7th, three on the 8th, one on the 9th, two on the 19th, and two on the 20th.[36]

Thus, by the time Frahm gave his statement of the 10th of October, the authorities had already committed to the Tesch case by ordering and carrying out the mass arrest of TESTA personnel. Given this commitment, the case could not be given up lightly. Although Sehm was the only witness against Tesch, and his statements had been directly contradicted by his friend Frahm, the case had to go ahead. On October 22, another version of Frahm’s statement was made, which attempted to remove these contradictions. The text then read:[37]

“I have not worked for the firm of TESCH and STABENOW but a friend of mine, Herr Emil SEHM, worked for this firm as a bookkeeper. He told me one night in the early part of 1943 that he did not want to work any more for the firm of TESCH and STABENOW because his principles did not agree with those of Dr TESCH, and he might also have told me of the gassing operations of TESCH and STABENOW at concentration camps, but I am not certain now.

In August or July 1945 Emil Sehm showed me a letter that he had written to the British Military Authorities. It said that Dr TESCH had been in BERLIN with the Commander of the Wehrmacht and Dr TESCH had been told […remainder of letter follows the version of October 10].“

The reader should compare this to Frahm’s statement of October 10th, and will readily see that the changes were exactly the removal of the two contradictions between Sehm’s story and Frahm’s.

1.1 The Interrogations of Drosihn and Weinbacher

The interrogation transcripts for Drosihn and Weinbacher, unlike those of Tesch, exist in full in both German and English. Neither knew anything about Sehm’s travel report, or about the gassing of humans. Their interrogations are particularly interesting, however, in that they give us a look into the operating procedures and ethical standards of the British War Crimes Investigation Team. The interrogations, in fact, exist in two different versions each in both German and English: an original transcript of the interrogations, which took place on October 17 in Drosihn’s case and October 16 in Weinbacher’s, and a doctored version.[38] The doctored versions have had certain passages embarrassing to the prosecution removed, but are still signed and certified as accurate transcripts by Captain Freud and the stenotypist. Altogether, then, there exist (1) a German original, with the passages to be removed indicated in pen, (2) an English translation of the German original, (3) a sanitized German copy with the offending passages removed, and (4) an English translation of the sanitized German copy.

What kinds of passages were thought worth removing? To start, the very beginning of Weinbacher’s interview was removed:

“Q. Take your hands out of your pockets if you come in here.

A. Yes, I have done it already,

(Owing to the obstinate behaviour of the prisoner Captain FREUD ordered the presence of an armed guard).”

What was this obstinate behavior? In the report on the case, it is stated that Weinbacher was “so insolent” during his interrogation that “special steps” had to be taken.[39] Another excised passage from the interrogation gives a sample of this “insolence”. After having first claimed that Dr. Tesch had bribed Weinbacher, something Weinbacher indignantly denied (the entire exchange being later excised from the transcripts), Capt. Freud then claimed that Dr. Tesch had given the members of the firm instructions about what to tell investigators. Weinbacher denied this, and in the exchange that followed (which was cut from the transcript) showed more of his “insolence”:

“Q. Don’t lie.

A. No. As sure as I am standing here, there was no question about it. You are under a misconception.

Q. Don’t shout at me.

A. I am speaking in the same voice as you are talking to me.

Q. Don’t become insolent. What did you get from Dr TESCH?

Q. I didn’t get anything. I can only say that you do not appreciate Dr TESCH” (German original reads: “daß Sie Dr. Tesch falsch beurteilen.”)

When Weinbacher denied that TESTA had specially secured files,[40] he was threatened by the interrogator, but the exchange was later removed from the transcript:

“Q. How do you like the prison? Apparently too well. We shall send you to a working camp [Arbeitslager] if you don’t want to speak the truth.

A. I can only tell the truth and nothing more. I can’t say anything but the truth.”

Dr. Drosihn’s October 17 interrogation experienced similar expurgations. As in Weinbacher’s interrogation, a passage to do with the disparagement of Tesch’s character was removed. (The first two lines of the following quotation were not removed; they are included here to provide the proper context.)

“Q. What did Dr. Tesch say when such an enormous order came?

A. ‘Good; that is a beautiful order.’

Q. He did not say: ‘Good, another 100,000 Poles or Russians dead’?

A. No, he never did say that. In my opinion, he would always have been against that.

Q. I am very much disappointed with you. I thought you would speak more openly.

A. I did so.

Q. No you did not. You did not say anything about the gassing of men.

A. I don’t know anything about it.”

In another removed passage Captain Freud expounded on the converted shower theory that dominated thinking about gas chambers at the time.[41] (He also made such a sketch and description of gassing showers during the interrogation of TESTA employee Johann Holst.[42])

“Q. We will show you how we found the gas chambers. (Captain FREUD makes a sketch). I show you the chambers of RIGA. These rooms had once been shower baths. The SS was standing armed on the roof, the people were driven into the yard, then the doors were locked and the SS pushed the people into the rooms, allegedly to take a shower bath. They were told that, then the doors were locked and the ZYKLON gas was sprinkled through the holes in the ceiling. After ten minutes the people could be brought to the incinerator, How many of these installations did you see?

A. Not a single one. In RIGA I only saw the normal installation.”

The questioning of Drosihn on Sehm’s travel report story was also cut, with the following text being removed:

“Q. I will tell you what records we have found. At the end of 1941 Dr Tesch was in BERLIN and had conferences with the highest officials of the Wehrmacht and the SS. And in the course of these conferences it was said literally: ‘Because the shooting of Jews is unhygienic it is suggested that BLAUSAEURE GAS should be used.’ That is to be read in black and white in a letter from the High Command. I am rather sure that you, too, took some part in this. What do you know about the destruction of men? But this time I don’t want to hear the same lies, but the truth.

A. I state once again that I heard of it only after the occupation.

Q. That is impossible for the shower baths were only camouflaged; there was no water there.

A. I assume that they were perhaps hot air chambers, but it is not allowed to build them like that, for that is not permitted by the law, that chambers must stand quite apart.

Q. It was a barrack standing alone. Didn’t you supply anything for it?

A. No, nothing. That is not the expert way and cannot be brought in accordance with the laws relating to BLAUSAEURE.”

As in Weinbacher’s interrogation, threats were removed from the edited version of Drosihn’s interrogation. First to go was a threat to hand him over to the Russians to be tortured:

“Q. I see, Dr DROSIHN. We won’t get anywhere like that. I had thought you would like to speak, but as you are not doing that, we must proceed differently with you; for we want to know what the firm had to do with the gassing of men. You know the firm’s position today, as well as yours, and that of the other gentlemen, Dr TESCH and WEINBACHER? Your sphere of activity was mostly in the East, such as AUSCHWITZ, RIGA, LUBLIN, ORANIENBURG, and all those places are now under Russian authority. We shall be forced to pass you on to the Russians who now deal with such cases and probably employ other methods to make you speak.

A. I cannot make any other statements. I can only assure you that my tongue has been loosened and that I will tell you everything.

Q. Until now you have not told us anything.

A. I must adhere to my statement that only after your victory did I hear that men had been gassed in the concentration camps.”

Also removed was a veiled threat against Drosihn’s wife:

“Shall we first hear [verhören, translation should be ‘interrogate’] your wife about [what Drosihn had heard about Auschwitz]? We want to spare her this.”

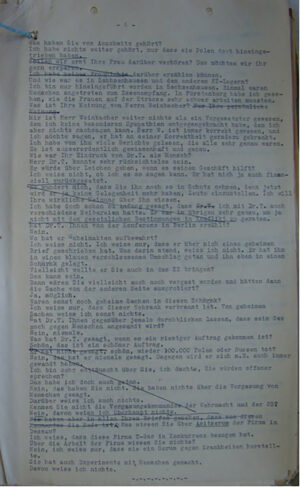

Figures 1 and 2 show pages from the original German transcripts of the interrogations, with the passages to be excised marked in pen.

The revelation of this procedure of sanitizing interrogation transcripts has significant implications, and raises the question of how far this practice extended to other similar cases of the time. Certainly, one must suspect similar alterations to Tesch’s interrogations, neither of which exists in a true original (meaning the copy actually taken down during the interrogation). However, there is also a strong possibility that similar acts took place in other British and American interrogations. In one similar case, there was testimony in the Congressional investigation of the Malmedy trial that the investigators engaged in extensive rewriting of interrogation-derived statements.[43] Interrogation materials are often not available in the original typed version, as seen in Figures 1 and 2 (with characteristic lack of formatting), but only in better-formatted, retyped versions. In light of the modifications demonstrated here, scholars cannot deny the very real possibility that they are dealing with doctored materials – “the interrogation as it should have been”. Though this is not the time to treat the subject thoroughly, one must remark that when using interrogation and trial materials, holocaust scholars have not shown adequate sensitivity towards the type of evidence with which they were dealing. It is no surprise that reading the prosecution’s file makes the accused look guilty: the prosecution was aiming for that effect, and often was not being particularly honest in the process. On the theme of caution with interrogation-derived statements, one should also note the penchant of prosecutors to use their own statements in the deposition of a witness. In simplified and somewhat caricatured form, the process looks like this: one begins with an interrogation as follows:

“INTERROGATOR: Statement 1 is true, right?

WITNESS: Yes.

INTERROGATOR: Statement 2 is true, right?

WITNESS: I guess so.

INTERROGATOR: Statement 3 is true, right?

WITNESS: No, definitely not.

INTERROGATOR: Statement 4 is true, right?

WITNESS: I don’t think so.

INTERROGATOR: Is it impossible?

WITNESS: Well, I guess I can’t prove it didn’t happen.”

Through the magic of the prosecution’s rewriting, this becomes

“DEPOSITION OF WITNESS: Statement 1. Statement 2. It is quite possible that Statement 4.”

In this way, the witness simply becomes the mouthpiece for as much of the prosecution’s case as he will assent to, or at least not explicitly deny. The appearance of voluntary or spontaneous admissions in the resulting statements makes them much more convincing evidence than the interrogation transcript itself would have been. This, of course, was intentional on the prosecution’s part. To give a simple example from the Tesch case, consider the following exchange during Drosihn’s interrogation:[44]

“Q. What was your impression of Dr TESCH as a man?

A. Dr TESCH could be very inconsiderate.

Q. He would step over corpses if it helped his business?

A. I don’t know whether I can express it that way. It is true he neglected my salary.

Q. It astonishes me that you still protect him thus, for now he will not have an opportunity to employ people. I want to know your real opinion of him.

A. I have already stated at the beginning that I had several quarrels with Dr TESCH. Besides, he was very correct and tried not to come into conflict with the law.

Q. Did Dr TESCH tell you about the conference in BERLIN?

A. No.

Q. Where did he keep secret records?

A. I don’t know. I only know that he wrote a secret letter about me. I don’t know what was in it. He put it into a blue, closed envelope and laid it in the upper shelf of the cupboard.

Q. Perhaps he wanted to bring you to a concentration camp?

A. That is possible. [Das kann sein.]

Q. Then you would perhaps have been gassed and experienced the matter from the other side?

A. Yes; possible. [Ja, möglich.]“

In his statement, this became

I also know that Dr TESCH kept a sealed envelope which probably contained my criticisms of the State in order to be able to blackmail me.[45]

1.2 Tesch’s Second Interrogation

On October 24, Tesch was interrogated by Anton Freud. This second interrogation does exist in German, but in a fragmentary form, severed into 31 numbered chunks. While the interrogation contains some particulars that are of interest in connection with specific points, some of which are cited elsewhere in this paper, the interrogation as a whole offered little new. Mainly, Freud took the opportunity to vent his anger and frustration over the weakness of the evidence the WCIT had gathered, accusing Tesch of engineering a coverup with his employees, and of burning key documents. At the time, there was still a realistic possibility that Tesch would be turned over to the Russians,[46] and Freud took the opportunity to threaten that because of the 4.5 million people he had killed, the Russians would rip out Tesch’s [finger and toe] nails.[47] Faced with Freud’s threats and name-calling, Tesch mostly confined himself to repeating his previous statements.

2. The Trial

The Tesch trial lasted from March 1 to 8, 1946. The Judge Advocate was C.L. Stirling, who had also presided at the Belsen trial. Major Gerald Draper started things off, reminding everyone what the trial concerned:[48]

“Zyklon B was going in vast quantities to the largest concentration camps in Germany east of the Elbe, and in those same concentration camps the SS Totenkopfverbunden were systematically exterminating human beings from 1942 to 1945 in an estimated total of six million human beings, of which four and a half million human beings were exterminated by the use of Zyklon B in one camp alone known as Auschwitz/Birkenau.”

The trial was conducted in English, and its transcript records only the English language versions of statements. The quality of the translation varied. A letter from Major Peter E. Forest, sent the day after the trial concluded, described the four interpreters. Captain Sempel received top marks, with Sergeant Rees a step behind. Sergeant Cunningham’s English was inadequate for the job, his translations incorrect, his manners poor. (“The Court was most displeased with his remark ‘Shut up’ to the Defending Counsel.”) Corporal Jacobson was too nervous and distracted to perform up to standard.[49] Certain problems of translation are evident in the transcript, for instance when the gassing of “mules” is mentioned (a mistranslation of Mühlen, the German word for “mills”).[50]

The main fact which the prosecution attempted to prove was that the defendants had known that the gas they provided was used for extermination. While witnesses for the gassings did appear, they were not the focus of the trial, and the “fact” of mass extermination with gas in concentration camps was largely taken as known, having already been “proven” at the Belsen trial. In establishing the defendant’s “guilty knowledge”, the vital witnesses were the trio Sehm-Frahm-Pook, as well as the TESTA secretaries Biagini and Uenzelmann. We will focus on the evidence which these witnesses presented at the trial, how it compares to their previous statements, and the pretrial machinations concerning how the case would be presented.

2.1 Sehm, Frahm, Pook

Sehm was the first witness to appear. He made a number of mistakes that damaged his credibility, such as alleging that TESTA had delivered gas to Dachau and Belsen,[51] and stating that “it was well known in the firm that Dr. Tesch was not a chemist, but a Doctor of Philosophy and interest only privately in the chemical science [sic].”[52] Sehm’s presentation of his story concerning the crucial travel report was consistent with his pretrial statements. With respect to the contentious question of what he had told Frahm, he stated that in the Spring of 1943 he had told Frahm all about the travel report, and Frahm, a “very temperamental person”, had “behaved in a rather violently anti-national socialist way.”[53] With respect to Wilhelm Pook, he stated that the latter “came back to Hamburg in October or November 1945 and we have been having discussions since.”[54]

Frahm was the next witness to appear, and contradicted Sehm’s account:[55]

“Q. Did [Sehm] tell you why he wanted to leave [TESTA]?

A. He indicated that things were going on at that firm with which his conscience could not agree.

Q. Did he particularise what those things were?

A. No. He did not give me any particular details because at that time to talk about such things was quite impossible.”

Wilhelm Pook and his wife Kate Pook did not appear until Day 3 of the trial. On direct examination Wilhelm Pook was not asked about the Sehm travel report, but did give an account of what Sehm had told him during the war:[56]

“Sehm told me that he was working at Tesch & Stabenow and that that firm supplied prussic acid for the territories in the east and that it was mainly a question of the killing of Jews and that Dr. Tesch undertook journeys there to give instruction about the manner of using that poison, and I know that Tesch & Stabenow furnished themselves this poison gas.”

Only on cross examination was he asked about the travel report. He confirmed Sehm’s story insofar as he stated that Sehm had told him about finding the travel report, read notes he had taken from it, and that he, Pook, had advised Sehm that it was dangerous to carry such a paper.[57] He did not, however, remember Sehm’s story about burning the note in an ashtray on the table:[58]

“Q. Did anything happen with this copy made by Sehm in your presence?

A. I cannot remember any more if he put it again in his pocket or what happened.”

Far more important than whether Pook could confirm Sehm’s bizarre tale of the travel report outlining the OKW’s plan to gas Jews at night in their barracks, however, was a fact revealed by Tesch’s lawyer Zippel. The reader may have noticed that Pook’s pretrial statements have not been mentioned. This is for good reason: they are not present in the files. While cross examining Pook, Zippel revealed that pretrial statements were taken from both of the Pooks. He pressed Pook on the discrepancy between his earlier statement and his trial testimony:[60]

“Q. Why did you not mention [the travel report] whilst you have been interrogated by Captain Lee, the British Interrogation Officer?

A. In the meantime I could think about it.

Q. Have you in the meantime spoken to Sehm about it?

A. Yes, we did, but we did not gain any new facts.

Q. When did you speak with Sehm about it?

A. Last week.

Q. Have you spoken to Sehm after Sehm appeared as a witness before this court?

A. Last week.[59]

Q. Did Sehm tell you what was the evidence given before this court?

A. It was only repetitions of what he had said before.

Q. Please answer my question now. Did he tell you what he gave as evidence before this court?

A. Yes he did – what was printed in the newspaper.

[…]

Q. Whilst interrogated by the British Interrogation Officer you could not remember that Sehm did show you a paper and yet now, months later, you can remember what was in this document.

A. We talked over this happening just as I gave the evidence a few moments before.”

Wilhelm Pook was followed on the witness stand by his wife, Kate Pook, who delivered similar testimony, with a few notable differences. First, she claimed that she had thought at first that the document Sehm brought with him was an original document but only later realized that it was a copy – a story which clashes with Sehm’s claim that it was just his own handwritten and fragmentary notes.[61] Second, unlike her husband, she managed to remember Sehm’s story about burning the note in an ashtray, although she was forced to admit that she might have merely been “reminded” of this by Sehm when he visited.[62] Third, in her original statement to the British interrogating officer, she had apparently mentioned something about Sehm showing her one of Tesch’s letters (rather than Sehm’s notes on a travel report, as she claimed at the trial), and she stated that she only remembered about the document after her initial statement.[63]

It is not entirely clear how Zippel acquired a copy of the pretrial Pook statements, or why they are not preserved in the records of the investigation and trial. Indeed, the casual reader of the Tesch investigation files could be forgiven for not noticing (either) Pook’s existence. From a few traces, however, we can reconstruct the events of the investigation involving Pook.

Sehm had alluded to Pook without mentioning him by name in his August 24, 1945 letter. His September 18 description of his confrontation with Tesch named Pook for the first time, giving a lengthy description. Sehm repeated his description of Pook in his October 10 statement. Pook, however, was located in the American zone, and was consequently not the easiest witness for the Hamburg-based team to get at.

On October 27, Ashton Hill, the commanding officer of the No. 2 WCIT, requested that a statement be taken from Pook:[64]

“It is requested that a statement be obtained from POOK who is now in the American zone, in order to corroborate the evidence of the chief informant Emil SEHM, who has made a statement on the lines set out below.” (Hill then quotes four paragraphs from Sehm’s statement.)

Making mention of this request, the investigative team’s report on the case notes:[65]

“In its present form there is very strong indirect evidence against all three accused but only weak direct evidence against Dr TESCH and no direct evidence at all against Herr WEINBACHER and Dr DROSIHN. The direct evidence against Dr TESCH can be strengthened slightly if a corroborative statement is obtained from Wilhelm POOK.”

Referencing the report, a November 9 letter stated that Pook was being searched for.[66] Eventually, No. 2 War Crimes Investigation Team received a message informing them that Pook had arrived in Hamburg on November 23:[67]

“RESTRICTED. CONFIRMING TELEPHONE CONVERSATION BENTHAM GREEN/ASHTON HILL RE GIFTGAS CASE AND DOCTOR TESCH. WILHELM POOK NOW REPORTED ARRIVED HAMBURG 23 NOV ADDRESS ALTONA STRESEMANNSTRASSE 71 BEI FAMILY MEYER. PLEASE ARRANGE IMMEDIATELY INVESTIGATION FOR CORROBORATION OF EVIDENCE OF EMIL SEHM AND REPORT ACCORDINGLY”

This message is dated only “02”, as in “the second day of the month”, at 1800 hours. The position in the file, however, indicates that the month was January. We will trace through the chronology of the pretrial period to see where Pook came back into the story. The report on the case, dating to early November, mentions only that a statement should be taken from Pook. A November 28 advisory report by Brigadier H. Shapcott recommended charges against Tesch only, suggesting that the cases of Weinbacher and Drosihn be left for a later date.[68] Though it listed all witnesses and other evidence to be brought, the report made no mention of Frahm or Pook. These two were also omitted from a December 12 list of witnesses to be called.[69]

On December 21, however, the charge was altered to include three defendants rather than Tesch alone. At this time, Frahm was added to the list of witnesses, but Pook still went unmentioned.[70] On January 3, referencing a telephone conversation between Smithers and Ashton Hill, Pook’s arrival was noted:[71]

“It has been reported that Wilhelm POOK has left the American zone and is at HAMBURG-ALTONA, Stresemannstrasse 71 by Family Mayer. An immediate interrogation has been ordered by this Branch to be conducted by a member of No. 2 WCIT, and the result will be notified to you accordingly if it is intended to call POOK as a witness.”

On January 19 both Pooks were on the witness list, but with a handwritten note that they were “not to be produced”.[72] Wilhelm Pook’s statement was acknowledged as received by 8 Corps District on January 31,[73] and eight further copies were sent on February 2.[74] On February 7, the originals of both Pook statements were passed on, along with copies.[75]

I have narrated these events in such detail to show the compelling evidence that statements from the Pooks were first taken at some point during January. It is important to establish this clearly because there is an intriguing circumstantial argument to the contrary. Here we return to the theme of the manipulation of witness statements by the WCIT. In addition to the Sehm statement of October 10 cited above, a second version of Sehm’s statement was prepared and is included in a set of copies of exhibits to be used at trial.[76] This version, which is given the same date, is identical to the normal statement, with one exception: Sehm’s discussion of his friend Pook, to whom he showed a copy of the mysterious travel report, is omitted.

The existence of this version of Sehm’s statement would appear, on first glance, to be linked with another case of document manipulation, namely that alluded to in the above mentioned November 28 advisory report, which states that Sehm should be presented as a witness “in accordance with Sehm’s statement as amended by this office.”[77] The question arises whether the Pook-less version of Sehm’s statement is that amended version. If so, it would be tempting to suggest that the Pooks’ failure to confirm Sehm’s story caused the British authorities to create a new, Pook-less statement. This would require the hypothesis of an additional, earlier, undocumented meeting between Pook and War Crimes investigators. The chronology of events related to Pook was given in such detail in order to show that such a hypothesis is untenable. The documentary record is too clear to allow for such speculation.

If the Pook-less Sehm statement is identical with “Sehm’s statement as amended by this office”, then the amendation was done prior to taking a statement from Pook, presumably having been performed in order to conceal Pook’s existence from the defense, since at the time his evidence remained a wild card. If the Pook-less Sehm statement is not identical with “Sehm’s statement as amended by this office”, then the latter was either for some reason not preserved in the Tesch trial files, or is nothing other than the standard version of Sehm’s statement, the true original not having been preserved. Whichever of these options one prefers, it’s clear that a great deal of document manipulation went on in the preparation for the Tesch trial.

2.2 Biagini and Uenzelmann

Aside from the trio Sehm-Frahm-Pook, the only witnesses offering evidence that Tesch and his fellow defendants had known that their gas was used to kill humans were two secretaries, Erna Elisa Biagini[78] and Anna Uenzelmann.[79] Neither of these witnesses told such a spectacular tale as Sehm, but they were seen at the trial as providing confirmation. Of the two, Biagini is the more interesting, in that she completely changed her story between her pretrial and trial statements.

In her interrogation, Biagini stated that she had not seen written materials concerning homicidal gassing, but mentioned that rumors on this subject had circulated at TESTA. These rumors, which she first heard in Winter 1942, were not given any credence.[80] The same story is given in her statement[81] and in the report on the case.[82] Her statements to this effect may well be true. Rumors concerning the gassing of humans did circulate in Germany during the war. It would not be surprising if some typists at a gassing firm gossiped about them. That said, Biagini claimed that she had heard the rumors from her fellow typist Erika Rathcke, which Rathcke denied in her interrogation, asking to be confronted with the witness who claimed this. She maintained this denial in the face of a threatening interrogation (“I tell you that you don’t speak the truth. That rumor was circulated in the office and you must know. I shall let you sit here for years if you don’t speak up.”). She had heard rumors about “idiots” being put to sleep (the euthanasia program), and knew of an institutionalized family member who had died shortly after a transfer, causing suspicion. She had not, however, heard anything about the use of gas for this purpose.[83]

At the trial, however, Biagini’s testimony was completely different. She first denied having heard rumors, but then told a new story about seeing a travel report:[84]

“Q. Did you ever hear any rumours about Zyklon B whilst you were with Tesch & Stabenow?

A. No rumours. What sort of rumours?

Q. Were there rumours about Zyklon B whilst you were with Tesch & Stabenow?

A. No rumours.

THE JUDGE ADVOCATE: When you were working with the firm, were there any rumours going about as to what Zyklon B was being used for?

A. I do not know for certain.

Q. Have you understood the question?

A. Yes.

Q. Let the court have an answer. It is a very simple question.

A. That the gas was used in concentration camps for disinfection.

MAJOR DRAPER: Did you ever hear that they were using the gas for any other purpose than for disinfecting vermin?

A. Yes.

Q. Will you tell us the circumstances and what you heard?

A. I was working at a document; I have read it – that it might be used for human beings as well.

Q. Do you say you read that yourself?

A. Yes.

Q. Having read that, did you mention it to any of your co-employees?

A. Yes.

Q. To whom and in what circumstances?

A. To Fraulein Rathcke. […]

Q. Did you learn anything else about Zyklon B being used for exterminating human beings whilst you were in that firm?

A. No, nothing else.”

Under cross examination, she stated that this report was one of Dr. Tesch’s travel reports, but did not remember anything about the context of the document. She could testify only to having read in a travel report something concerning the possibility that Zyklon could be used against humans.[85] When questioned about the matter, Tesch thought that Biagini’s new story might be based in fact, and offered the hypothesis that a student in one of his courses might have asked him about the effect of Zyklon on humans, and he might have taken note of this in a travel report. When challenged on this he emphasized that he indeed did frequently write down students’ questions in the travel reports from his courses, that he could prove this, and that students did indeed ask such questions at his courses.[86] Rathcke, for her part, denied that Biagini had told her about this document.[87]

The prosecution clearly did not know Biagini’s new story before the case went to trial, as can be seen from the fact that Major Draper mentioned her old story in his opening speech.[88] Her reasons for changing her story are not apparent. Like her old story, her new story is perfectly plausible and not at all incriminating, despite the prosecution’s insinuations. Her new story certainly cannot be interpreted as confirmation of Sehm’s travel-report story.[89] While both stories involve a travel report, the two descriptions of that travel report are quite different, as Tesch himself noted at the trial.[90]

The other TESTA secretary to offer evidence that Tesch had known of gassings was Anna Uenzelmann. Unlike Biagini, she stuck to her pretrial statements: at some point in 1942, after returning from Berlin, Dr. Tesch had said something to the effect that he had heard that there were plans to use Zyklon to kill humans, but had not given any details whatsoever.[91] Tesch denied that there was any truth to Uenzelmann’s story, and noted that “Frau Unzelmann is well known in the business as a very confused person”, and suggested she may have become confused during the years since the event and made a mistake.[92]

2.3 Excess Zyklon Supply?

It would be difficult to overstate how much emphasis was placed on the size of the Zyklon supply to Auschwitz during the Tesch investigation and trial. According to the prosecution, the supply was so large that Tesch must have known that the gas was used for extermination. TESTA’s employees, under arrest at the time, were pressured to provide support for this argument. Meanwhile, in his first interrogation, Tesch had indicated skepticism towards this line of argument:[93]

“Q. I am going to tell you something instead of asking the questions. 5 Million people died from gassing in Auschwitz. What do you understand from that?

A. It is news to me.

Q. Tonight you are learning something, are you not? You are astounded, are you not? So some of the gas which went in did not kill merely bugs, did it?

A. I do not know; there were a lot of bugs in Auschwitz.”

In one case, the investigation team managed to secure a sort of endorsement for the excess Zyklon supply [hereafter EZS] argument, but only based on the assumption that Auschwitz was much smaller than it in fact was: a statement taken from the gassing technician Gustav Kock[94] stated that he would be “astonished” at Zyklon orders of one ton monthly for two years from a camp the size of Neuengamme.[95] He repeated this statement at the trial.[96] Auschwitz, which had ordered 19 tons in two years, was meant, and the interrogator had suggested to Kock that Auschwitz was the size of Neuengamme or Gross Rosen. In another case, the British interrogating agent explicitly stated that Auschwitz was a normal sized camp, and was smaller than Sachsenhausen.[97] The confusion about the size of Auschwitz was compounded by the statements of the gassing technician August Marcinkowski, who recounted an early trip to the camp:[98]

“In March 1940 I carried out a gassing in AUSCHWITZ. This was just before it was due to become a concentration camp. At this time AUSCHWITZ consisted of seven to eight one-storeyed [einstöckigen] stone houses and we used about 120 kilograms of ZYKLON gas to gas it.”

Marcinkowski was called at the trial and repeated the story, stating this time that 120 to 130 kg of Zyklon had been used.[99] Captain Anton Freud, in turn, repeated this claim while interrogating Tesch, in order to prove that the Zyklon supply to Auschwitz was excessive:[100]

“Q Not conspicuous! Do you know what people have said about you? If a camp ordered 1 ton of gas a month, throughout 2 years, and you didn’t notice it, then you are either moronic or you don’t want to know it. You know that the entire Auschwitz camp can be gassed with 120 kg.

A. One barrack?

Q. No, the entire Auschwitz camp.”

The possibility that the Auschwitz for which Tesch supplied gas might have been somewhat larger than the Auschwitz which Marcinkowski gassed in early 1940 seems not to have occurred to Freud. Indeed, it was taken for granted by the investigating team that the quantity of Zyklon supplied to Auschwitz was so immense as to be sufficient to prove that large scale extermination of humans occurred at the camp. An entire segment of Tesch’s October 24 interrogation is devoted to Anton Freud’s rant against Tesch’s claim that the quantity supplied was not surprisingly large:[101]

“Q. There aren’t enough insects in all of Germany that one needs 1 ton Zyklon per month. If a camp ordered that much, you must have been aware that it wasn’t only used against insects. Do you know what your people have said about that? That you are an idiot or you didn’t want to know what the gas was used for.”

Here Freud was alluding to Gustav Kock’s statements mentioned above, originally made during his interrogation of October 20.[102]

At the trial, the prosecution strenuously objected to Tesch’s statement that Auschwitz’s demand for a larger supply of Zyklon was unsurprising due to the fact that Auschwitz was a larger camp.[103] Their plan for the EZS argument was to claim, based on inaccurate statements from Drosihn, that the SS could not carry out disinfection of barracks without the help of TESTA technicians, but could only perform gassings in gas chambers. Therefore all Zyklon sent to Auschwitz had to be used in (delousing) gas chambers or for homicidal purposes. As the quantities ordered were in excess of those needed by delousing chambers, therefore Tesch had to know that Zyklon was being used for mass extermination of humans at Auschwitz. Tesch rejected these arguments as well:[104]

“Q. Do you know how many delousing chambers there were in Auschwitz in 1942?

A. I do not.

Q. Do you know how many you supplied to this concentration camp.

A. Yes

Q. How many, roughly?

A. As far as I know we did not supply any.

Q. You would agree, would you not, that seven thousand kilograms of Zyklon B gas is unlikely to have been used for the purposes of delousing chambers?

A. On the contrary, I even now today am of the opinion that even a bigger amount could have been used.

Q. And you say the same about twelve thousand kilograms in 1943?

A. Yes, that means 1,000 kilograms a month and that is not exaggerated for a big camp.”

Despite the prosecution’s best efforts, the EZS argument consistently failed to persuade competent observers. The gassing technicians to whom it was put invariably rejected it, the only exceptions being in those cases where the technicians were given erroneous information concerning the size of Auschwitz.[105] Tesch rejected it, as did Weinbacher[106] and Drosihn, the latter even under the assumption that the Zyklon sent to Auschwitz cannot have been used for disinfecting barracks, but only in gas chambers or homicidally:[107]

“Q. If it is so from the books of the firm that 7000 kgs. [of Zyklon-B] went to Auschwitz alone [in 1942], would that strike you as the proper quantity for disinfecting only in gas chambers?

A. I do not know the conditions in Auschwitz, but I think it may be possible. […]

Q. Auschwitz took in 1943 12000 kgs. of the gas. Would you have been surprised if you had heard that?

A. I knew that Auschwitz was a very big camp.”

The prosecution also put the argument before Karl Schwarz, Professor emeritus at the (Hamburg?) Institute of Hygiene, who declined to endorse it.[108]

Despite its consistent rejection by everyone with expertise in gassing, the EZS argument remained the prosecution’s favorite, and went on making the rounds with holocaust historians. For example, in a well-known anthology on the alleged National Socialist gassings, the size of the Zyklon deliveries to Majdanek was held to be proof that they were intended for homicidal use.[109] While the EZS argument was repudiated by Jean-Claude Pressac,[110] it was resurrected by Robert Jan van Pelt in connection with the Irving-Lipstadt trial.[111] Van Pelt’s shoddy arguments need not concern us beyond a few brief remarks.[112]

Van Pelt uses Zyklon delivery quantities from Tesch trial documents, but these numbers are not complete and hence not suitable for comparisons of the sort van Pelt wants to draw.[113] The quantities van Pelt quotes do not include the gassings that TESTA carried out themselves in the camps,[114] notably in Sachsenhausen and Neuengamme, where these quantities are large enough to dramatically alter the results of van Pelt’s calculations for 1942.[115] TESTA’s books record that in that year it gassed a total of 334,720 cubic meters at Sachsenhausen and 112,260 cubic meters at Neuengamme. At 15 grams per cubic meter, the standard concentration for gassing barracks,[116] this means the use of 5,020.8 and 1,683.9 kg of Zyklon, respectively. These quantities dwarf van Pelt’s annual totals of 1,438 and 180 kg for these two camps. When the two sets of figures are added together, it appears that the quantities of Zyklon going to Sachsenhausen and Neuengamme in 1942 were, if anything, excessive in comparison with the quantity going to Auschwitz, perhaps as a result of German fear that epidemics in these camps might spread and affect the nearby urban areas.

Further, van Pelt assumes that the Zyklon supply to camps other than Auschwitz, Neuengamme for example, was adequate on a per-prisoner basis, while in reality Neuengamme prisoners complained that delousing was scarcely ever done, and blamed the camp administration for this omission, which was the result of a shortage of Zyklon.[117] Moreover, citing the Nuremberg document NI-9912 (of little direct relevance to Auschwitz), van Pelt assumes that the Auschwitz delousing chambers would have used a concentration of 8 grams per cubic meter. The concentration normally recommended by TESTA, however, was 10 grams per cubic meter (Type ‘D’). Even worse, van Pelt assumes a concentration of 5-8 grams per cubic meter for the delousing of barracks. TESTA’s recommendation for the gassing of barracks was 15 grams per cubic meter (Type ‘E’).[118] Correcting this last figure alone suffices to overturn van Pelt’s analysis.

Van Pelt compounds his errors by assuming that all camps require the same amount of Zyklon per prisoner, without considering regional differences in hygienic conditions. This allows us to return to the arguments made at the Tesch trial. In his first interrogation, Tesch remarked on the regional difference in the need for disinfestation, stating that “Eastern territories were particularly in danger of spotted fever”, although this was not said in the context of the EZS argument.[119] In his second surviving interrogation he made this point as well, this time in the EZS context, responding to the suggestion that the deliveries to the concentration camps were “a little strange” with a reference to the great danger of louse infestation in the east.[120]

Tesch elaborated on this point at his trial, noting that there was a greater infestation problem in the east than in the west,[121] and stating that among the reasons he was not astonished by the quantity of Zyklon supplied to Auschwitz was that “Upper Silesia was a much infested province of Germany, and because I experienced in Poland a sort of infestation with insects and vermin as I had not thought possible.”[122] When the prosecution expressed incredulity that Tesch should not have thought it strange to see Auschwitz order four times as much gas as Sachsenhausen over a certain period,[123] Tesch observed yet again that “one is a territory which is infected by vermin”. He explained that this was both general knowledge (“We knew that the whole of Poland and Upper Silesia were territories which were very badly infested”) and something he knew on the basis of his own experience.[124]

The prosecution also knew Tesch’s statement to be true. Their own trial Exhibit DB, a travel report dated March 20, 1941, reporting on Tesch’s experiences in Upper Silesia from 7-11 March, contained a discussion of the poor sanitary situation in Upper Silesia, including the remark that while the disinfestation plan was not yet definite, all were agreed that “something radical must take place.”[125]

Finally, in his attempt to obtain an upper bound for the amount of Zyklon that could have been put to “ordinary” use, van Pelt assumes that the entire supply of that product delivered to the Auschwitz complex had to be used in either the Stammlager or in Birkenau. He gives no justification for the assumption that the other Auschwitz subcamps never required Zyklon. The need to supply subcamps was repeatedly mentioned at the Tesch trial.[126] As van Pelt cites the trial transcript, it is unclear how he remained ignorant of this fact; the most charitable interpretation is that while he found it a fine thing to cite the trial transcript in support of his arguments, he did not feel obligated to go the trouble of reading it.

2.4 Sentence, Appeal, and Execution

Tesch and Weinbacher were found guilty and sentenced to death,[127] while Drosihn’s groveling earned him an acquittal. On March 19, Tesch submitted a petition against the judgment, as did Weinbacher the next day. Both men referred to the written appeals of their lawyers.[128] Tesch’s lawyer Dr. Zippel wrote a lengthy appeal which addressed a number of issues which had looked bad for Tesch during the trial. Chief among these was the issue of large gas chambers. Tesch had made various denials concerning his ignorance of large size gas chambers. At the trial, the prosecution sought to destroy his credibility by showing that these were lies. Drosihn wrote a statement on appeal concerning these large gassing facilities:[130]

I hereby declare under oath that the small 10 cbm. normal gas-chambers, which were used for quick delousing of clothing and simultaneous bodily delousing of the wearers of this clothing, f.i.[129] in barracks, are unsuitable for the delousing of winter clothing for the troops, which is returned from the front in large quantities during the spring and summer months by car, lorry, or truck loads for repair, because this material was continually brought to the collecting stations of the Army Clothing Departments, and had then to be taken in hand. For this purpose I therefore considered the employment of large gassing rooms more practical than the corresponding number of small chambers. The places known to me indeed all only used large rooms for gassing, but did not install typical gas chambers. As instances I would enumerate the clothing department of the Heeresgruppe Nord

1) in Riga – Mühlgraben

1 gassing room of 1500 cbm.

2) in Pleskau

1 gassing room of abt. 150 cbm.

furthermore the Field Clothing Department of the air force Riga

3) in Riga – Ilgeziem

1 gassing room of abt. 180 cbm.

Big rooms have the advantage of a considerable saving in building material for the construction of inner walls, and that instead of many equipments only one is required and the handling of the clothes (taking and handing out) is quicker and simpler. By extending the time to 8 – 24 hours for the gas to take effect in comparison to the gassing duration of not quite one hour with simultaneous personal (bodily) de-lousing, the gyratory equipment could be dispensed with altogether.

In the repair workshop of the Reichsbahn in Posen finally whole trains with military winter-clothing were regularly deloused by means of Zyklon in truck loads with afore-mentioned Pintsch Tunnel. This disinfecting establishment of abt. 500 cbm. was not only arranged to be operated with heat but also for the production of sub-pressure, so that quick time for the gas to take its effect and high outputs could be attained. The tunnel in Posen is illustrated on the page before last of the Testa-Fibel regarding Zyklon.”

This confusion appears to have resulted in part from the prosecution’s use of the term Gaskammer to designate all kinds of gassing spaces, even the kind that gassing professionals would call generally a Gasraum, and in part from the prosecutors’ failure to consistently distinguish between equipment that TESTA themselves supplied and equipment that they had merely heard of. Thus in his interrogation, Drosihn says that he has never heard of large Gaskammern one minute, and immediately afterwards discusses an immense gassing facility in Riga.[131] This is clearly not an attempt to deceive, but rather proof that he did not classify the Riga facility as a Gaskammer. The fact that the term Gaskammer was assumed to have a somewhat restricted usage is also supported by the interrogation of Gustav Kock, who distinguished an improvised Gasraum from a Gaskammer.[132] Thus, the prosecution’s belief that Tesch was lying in his statements concerning large gas chambers is simply the result of their failure to understand the usage of the relevant specialized vocabulary.

Tesch’s lawyer also sought to call for the testimony of additional scientists as character witnesses, including the Nobel laureate Otto Hahn.[133] Such gambits were tried by any number of accused Germans, and rarely did much good. A highly favorable personal letter from Léon Blum did nothing to prevent Dr. Schiedlausky from being sentenced to death at the British Ravensbrück trial.[134] British agent Sigismund Payne Best’s highly sympathetic account of Sachsenhausen commandant Anton Kaindl[135] did nothing to prevent the British from transferring Kaindl to Russian hands and to his death in imprisonment. Even more futile was Kurt Eccarius’s wife’s attempt to aid her husband by providing his former prisoner Martin Niemöller as a witness to his character: by the time she wrote, he had already been turned over to the Russians.[136]

Attempted help came from outside as well, as Fritz Kiessig, who had worked with Tesch’s company on disinfestation in the east, wrote to offer his services in their defense. His letter reads:[137]

“Dear Sirs,

On the evening of 2nd. March I heard from a British wireless station that three gentlemen of your firm had been arrested for having participated in gassing operations in the East.

Whilst I was in the O.K.H.B of the Adm.Amt V2 during 1942/43 I also had to do among other matters with the entire de-contamination problem and collaborated a great deal with your good firm or respectively with one of your directors in this question. This matter is therefore not unknown to me and as far as it concerns the section ‘Army’ of our forces the happenings in ‘gassings’ as indicated in the British radio are entirely new to me.

If you should have any interest in my evidence I will gladly hold myself at your disposal, as the practices of the firms occupying themselves in the east with de-contamination are known to me from personal experience.

Yours faithfully

(signed) Fritz Kiessig

Oberfeldintendant a.D.”

The letter was received only after the trial had finished. In his appeal, Zippel informed the authorities of the letter, and requested “that arrangements be made to cross-examine this witness” in order to confirm or refute Sehm’s claims.[138] This was not done. In a memorandum recommending confirmation of the sentences, Brigadier H. Scott-Barrett claimed that the appeals “do not disclose any substantially new matter.”[139] The sentences were duly confirmed. The death warrants were signed on April 26 and executed on May 16.[140]

Several weeks later, Tesch and Weinbacher’s lawyers filed a protest, noting that neither they nor the families of the victims had been informed that the execution had been scheduled or even that it had taken place. Their complaint was forwarded to the headquarters of the British Army of the Rhine, with the observation that “It would appear unnatural that the nearest relatives of a man about to be executed are not advised of the forthcoming execution,” and the question, “Are relatives entitled to receive the body for interment?”[141] The reply was negative, and read:[142]

“Accused sentenced to death are not notified that their sentences have been confirmed until the evening before execution. It is undesirable that there should be any demonstrations in connection with executions and it is therefore necessary to withold any information relating to the dates of execution until they have been carried out. In this latter connection, the question of notifying next of Kin that death sentences have been carried out and giving notice of confirmation of prison sentences, is at present being considered […] It has been decided that bodies of executed persons will not be handed over to next of kin, or their place of burial made known.”

2.5 The Theft of Tesch’s Property

In the absence of substantial direct proof of Tesch’s guilt, a large portion of the prosecution’s strategy fixed on portraying him as a liar. The report on the case gave a list of his alleged lies, and those of his co-defendants.[143] One of Tesch’s alleged lies was the claim that when a British agent left the room on October 23, he had not exchanged whispers with head bookkeeper Zaun. The prosecution laid out their view of the incident:[144]

“Arrangements were made for the firm to be allowed to continue business after the release from prison of all its members except Dr TESCH, Dr DROSIHN and Herr WEINBACHER. Military Government appointed Alfred ZAUN, the former Chief of Accounts, to act as manager in the absence of Dr TESCH. In order to obtain the necessary written authorities, Herr ZAUN applied for a personal interview with Dr TESCH, which was granted and arranged for 23rd October. The opportunity was taken to lay a trap in the form of a microphone in the office in which the interview was conducted, and a German stenographer was detailed to record the conversation.

As a cover, in order not to rouse the suspicions of either Dr TESCH or Herr ZAUN, an interpreter of this Team was initially ordered to remain in the room, being summoned out by a bogus telephone call. Immediately he had left the room Dr TESCH and Herr ZAUN’s conversation dropped to a whisper which could not be understood; but certain passages were recorded which revealed that Dr TESCH had handed over to ZAUN his wallet containing RM 3,700 and certain personal possessions to be given to Frau TESCH. The failure of this ruse to obtain any concrete evidence, owing to the fact that the microphone apparatus was not sufficiently tuned for whispers, was unfortunate. However, there is little doubt that quite a considerable amount of whispering was interspersed between normal conversation, and great suspicion fell upon both these persons. At the subsequent interrogation of both of them, done independently, they both strongly denied that any whispering took place. The possibility of ZAUN being re-imprisoned was seriously considered, but it was felt that he still was blameless as regards the main crime that was being investigated; further, he would be of less value to the Team in the conduct of the investigation if in prison than he would be at large.”

During that period, Tesch had given Zaun valuables to pass on to Tesch’s wife. Resentful at the failure of their ploy, the British confronted Tesch during his October 24 interrogation, claiming that he had tried to bribe Zaun:[145]

“Q. Herr Zaun is very sorry that he could not bring your things to your wife, but he found that RM 4,000 was too small a bribe.

A. That was not a bribe.

Q. You want to deny that you gave Herr Zaun money?

A. No, I gave Herr Zaun RM 3,700, which was not supposed to be a bribe; he was supposed to deliver it to my wife.

Q. Did you have permission for that? Herr Zaun told us all the secrets that you shared with him there, and as a bribe you gave him money.

A. I can only say that we shared no secrets, and he was supposed to give the money to my wife.

Q. What else was he supposed to give your wife?

A. My fountain pen, my watch, my rings.

Q. What else?

A. I don’t know.

Q. What else? Penholder, perhaps a tie pin?

A. Yes, that also.

Q. And letters to your wife?

A. No.

Q. Tasks for your wife?

A. No, I did not say that to Herr Zaun. I only said that he should give the money to my wife.

Q. No tasks for your wife? Herr Zaun has informed us otherwise.

A. I only said that he should bring the gold securely to my wife.”

It should be mentioned that the investigation team was already accusing Zaun of being bribed a week before the meeting,[146] and that they made such accusations very freely. The questioning of Tesch continued to address alleged whispering:[147]

“Q. What did you whisper yesterday with Herr Zaun?

A. Nothing, we did not whisper anything. I spoke to him only on points due to business affairs.

Q. What did you whisper?

A. No, we did not…

Q. You did not whisper. It did not occur to you at all to lower your voice. You continued to speak normally when we were outside?

A. Yes, I did not whisper.”

Tesch reiterated this version of events in his statement.[148] According to the description of the incident quoted above, Zaun was also interrogated about the alleged whispering on October 24th, but the statement taken from Zaun on that same day contains no mention of the meeting with Tesch, or of whispers, or of bribes,[149] and the transcript of the interrogation is not present in the case files.

As for the property which Tesch had tried to pass on to his wife, it was confiscated by the British. On January 23, 1946 – three months after this incident – WCIT No. 2 transferred the property of Tesch, Weinbacher, and Drosihn to Property Control. The receipt included some of the items taken from Zaun (fountain pen, pocket watch, tie pin) along with other items, but not Tesch’s rings, and it included only 3,500 marks, rather than the 3,700 Tesch had given to Zaun.[150] More precisely, they claimed to have handed over the property. The property was not returned (just as the families were not informed of the executions). Eventually, a custodian was appointed by the British military government to look for the property. He wrote to the war crimes investigation section of the military government:[151]

“According to information received from Mr. Alfred Zaun, a bookkeeper in the firm of the deceased, the following objects were taken from Dr. Tesch on 23 October 1945 in the course of an interrogation held after his arrest in the War Crimes Enclosure in Hamburg […].”

Lt. Col. R.A. Nightingale’s reply noted that the gold wedding ring and gold diamond ring were not contained on the receipt.[152] Property Control Section, however, reported:[153]

“No trace of this property could be found in Hamburg nor is the name of Capt. H.B. Bursar, S.O. III P.C., who is supposed to have signed the receipt, known at this HQ.”

While there is no certainty here, it appears that someone in the war crimes investigation team invented H.B. Bursar (note the name!) and forged the receipt in order to cover up the theft of Tesch’s property.

It wasn’t only the investigative team that had financial motivations. Emil Sehm, who had been so keen to stress his “top secret” knowledge in his initial letters, hoped for some gain from the case, and claimed compensation as an expert witness for the period in September 1945 during which he worked on the case, but after a series of correspondence it was found that he was completely ineligible for such wages,[154] which were up to 3 RM per hour, or 6 in exceptional cases, in comparison with ordinary witnesses’ wages of 20 Pf. to 1.50 RM.[155]

3. Miscellaneous Elements

We will take the opportunity to gather a number of pieces of information of interest which are contained in the files of the Tesch trial. The collection is by no means comprehensive.

3.1 The Witness Pery Broad