Auschwitz: Technique and Operation of the Gas Chambers

An Introduction and Update to Jean-Claude Pressac’s Magnum Opus

In 2017, a German publishing company asked me to contribute a thorough introduction to a reprint edition of Jean-Claude Pressac’s 1989 book of the same title. Unfortunately, this German publisher went out of business in late 2018, so no such reprint ever appeared. My introduction is still valuable, though; hence I published it in January 2019 as a stand-alone book.

Pressac’s 1989 oversize book of the same title, which can be accessed online at t.ly/2Dg-S, was a trail blazer, as its many reproductions of documents from the Auschwitz Museum’s archives made them accessible for the first time to the general public. The book is still valuable today, but after decades of additional research, Pressac’s annotations are outdated. My book of the above title and subtitle summarizes the most pertinent research results on Auschwitz gained during the past 30 years. With many references to Pressac’s epic tome, it serves as an update and correction to it, whether you own an original hard copy of it, read it online, borrow it from a library, purchase a reprint, or are just interested in such a summary in general.

In this issue of Inconvenient History, the first eight of its total of 37 chapters are reprinted. The first chapter points at the cause why revisionist research such as the one summarized here is both important but also largely ignored and suppressed.

An Allegory

David had a difficult early childhood. His drug-addicted parents mistreated and neglected him. At the age of two, the local children services intervened. At that point, David was malnourished and emotionally disturbed. David was assigned to a new “home” with foster parents who were more interested in the support money they got from the authorities than in David.

During the first years of his life, David learned not to trust the people around him. In order to survive, he had to learn how to lie, cheat and steal. Because no one was giving him positive, affectionate attention, he developed all kinds of tricks of negative attention seeking: he told wild, invented stories, pretended to suffer, and pushed people’s buttons by being disrespectful, sassy, and by irritating them with provocative pranks.

Technique and Operation of the Gas Chambers. An Introduction and Update

to Jean-Claude Pressac’s Magnum Opus (132 pp. 6”×9”; Holocaust Handbooks, Vol. 42) is available as paperback and eBook from Armreg.co.uk.

After parental rights were terminated, David was eventually adopted by parents who wanted to help him overcome his childhood trauma. They even included their own biological children in that project.

First they vowed to do everything to fulfill David’s wishes so that all his needs would be met at last.

Next, there were to be no more punishments. After all, David did not lie because he was a bad person but because he had been traumatized so deeply. One really had to empathize with this.

When David was mean to the other kids, they had to overlook this, too.

From now on, David no longer had to fear any punishment, except for an occasional mild reproof when he told wild but untrue stories, cheated while playing, or bullied other kids. After all, a child who had suffered so heavily in the past could not be made to suffer again.

When his adoptive siblings protested on occasion because they perceived David’s special treatment as unfair, or when they even accused David of lying or bullying, his siblings were rebuked or even punished for being so insensitive. David’s siblings were not allowed to criticize him.

David received this privileged treatment for 14 years in the house of his adoptive parents before he came of age and began his own independent life.

What had David been taught during these 14 years?

David had learned that he is entitled to the people around him lip-reading his wishes and fulfilling them without resistance when possible.

David had learned that not he will be punished for his lies but those who dare criticize him for them.

David had learned that he can torment his fellow human beings to a certain degree without being held responsible for it.

David’s parents had raised a monster.

Introduction

The Dutch cultural historian Dr. Robert van Pelt stated once that the crematoria of Auschwitz-Birkenau, as the killing sites of hundreds of thousands of Jews, are the epicenter of human suffering.[1] But how does he know what transpired in those buildings, of which nowadays only ruins or foundation walls are left?

Anyone questioning their own knowledge – or that of another person – on any subject should start with simple questions such as these:

How do I know that?

Why do I think I know that?

What is the basis of what I consider to be knowledge?

When we talk about historical topics, our knowledge, in a nutshell, is ultimately based on three types of evidence: material remains, documents, and testimonies. The present book on Auschwitz deals primarily with documents and to a lesser extent also with material remains. Testimonies are almost irrelevant. This may surprise many readers, because those familiar with the subject know that there is a veritable deluge of testimonies, especially since several organizations began to systematically record survivor memories in filmed interviews in the 1990s. In addition, the shelves of larger public libraries are chock-full of memoirs and testimonials, not to mention the many statements made during various criminal proceedings. It is no exaggeration to say that what most of us consider to be knowledge of Auschwitz is based precisely on these testimonies. And that’s the problem.

French historian Jacques Baynac expressed it in 1996 as follows:[2]

“For the scientific historian, an assertion by a witness does not really represent history. It is an object of history. And an assertion of one witness does not weigh heavily; assertions by many witnesses do not weigh much more heavily, if they are not shored up with solid documentation. The postulate of scientific historiography, one could say without great exaggeration, reads: no paper(s) [=documents], no proven facts […].”

Witnesses can err, omit important things, say only half the truth, exaggerate and understate, fib, lie and cheat, and all shades in between. Above all, we must always be aware that our brains hate ignorance. When we do not know something, we consciously and subconsciously tend to fill in the gaps in our knowledge or memory with what’s at hand: guesses, clichés, hearsay, rumors, etc. We all do this all the time, every day. Our brain is a master at extrapolating and interpolating.

Whoever wants to write exact, scientific history has to verify the reliability of testimonies. If it turns out that a witness has to some degree stated things that are untrue, then we must be allowed to ascertain this, and then we must draw consequences from it, namely that we reject the statement partly or entirely, or we completely reject a witness as untrustworthy, depending on the severity of the deviation from the truth.

And this is where the circle is completed that I opened with my initial allegory: Anyone who accuses David of not telling the truth or even of lying runs the risk of being persecuted to a greater or lesser degree by social punishment or even criminal prosecution. Under such a Sword of Damocles, historiography cannot conduct dependable, exact research. Fear of social ostracism or even legal consequences lets many researchers completely avoid the topic. If it is nevertheless taken up, then usually either with an ideological zeal that wants to uncritically believe everything David claims, or for safety’s sake in a compliant, uncontroversial way by parroting what the mainstream expects. Hence, the scientific quality of modern Auschwitz research by established, “respected” historians is accordingly pathetic, because anyone merely asking the wrong questions, let alone answering them in an unwelcome way, is no longer “respected”, but ostracized and marginalized.

Either you believe just about everything David says, or you’re a Nazi. Since the Mark of Cain called “Nazi” is equivalent to a social death sentence, even those who harbor doubts feign that they believe. Well, almost all…

The only way out of this dilemma is to make do without David, that is, without testimonies, and to retrace the events of history with what evidence is left: documents and physical traces.

In the 1980s, French hobby historian Jean-Claude Pressac recognized this dilemma and dared to solve the problem by trying to prove only with documents that the many testimonies about mass-extermination events at the Auschwitz Camp are essentially true. He succeeded in gaining the support of many respected individuals and institutions for this project, including the Auschwitz State Museum, the Commission of the European Communities (forerunner of the European Union), the Socialist Group of the European Parliament and the Beate Klarsfeld Foundation.[3] The result was a huge, 564-page book in DIN A3 landscape format (11.7 in × 16.5 in) featuring reproductions of hundreds of original German wartime documents on Auschwitz which were thoroughly annotated by Pressac. With this trail-blazing book titled Auschwitz: Technique and Operation of the Gas Chambers, whose critical analysis is one of the main focuses of the present book, international Auschwitz research for the first time obtained a solid foundation supported by documents.

Of course, research has not stood still since then. Due to the collapse of the Eastern Bloc in the late 1980s and early 1990s, many archives were made accessible that hitherto had been either completely inaccessible or accessible only to selected researchers.

Take, for instance, the files of the Central Construction Office at Auschwitz. This was the authority that was responsible for all construction projects in the camp, including the crematoria that, according to witness claims, contained homicidal gas chambers. Until the early 1990s, historians believed that the files of this authority had been destroyed in late 1944 or early 1945 shortly before the withdrawal of the Germans from the Auschwitz Region. But that was not the case. After the Red Army had captured the camp in January 1945, the files of this authority were quietly and secretly transferred to Moscow, where they were kept under lock and key until the early 1990s. The files are today in the Russian War Archives (Rossiiskii Gosudarstvennii Vojennii Archiv).

Other documents of the Auschwitz camp authorities are today in the Russian Federal Archives in Moscow (Gosudarstvenni Archiv Rossiskoi Federatsii), while some files of the Waffen-SS that deal with Auschwitz – the Auschwitz-Birkenau Camp was originally planned as a Waffen-SS PoW camp – found their way into the War Archives of the Waffen-SS, which is today stored in the Czech Military History Archives in Prague (Vojenský Historický Archiv).

In addition, there are archive holdings at the Auschwitz Museum itself as well as various files on criminal proceedings in Poland, which are now in Warsaw.

A small part of the collections made accessible in Moscow was evaluated by Pressac in the early 1990s, which inspired him to write a second book on Auschwitz, which I will address at the very beginning of the main text of this book.

In the following years, other researchers further analyzed these records and, based on Pressac’s magnum opus, brought new findings to light. The main text of this book gives an overview of these research results while frequently referring to Pressac’s magnum opus. Hence, anyone who wants to examine what is stated here about Pressac’s work needs to have access to his work. Unfortunately, Pressac’s magnum opus is no longer available today in its original print version, and only major libraries carry copies of it. Although the book was posted in its entirety on the Internet – www.historiography-project.com/books/pressac-auschwitz/ – the main advantage of the print version of Pressac’s book – that it reproduced many documents in high resolution – does not apply to the low-resolution Internet version. It therefore makes sense to make Pressac’s magnum opus accessible again in a reprint. However, as it is partly obsolete by further research, it would be irresponsible to offer Pressac’s statements from 1989 as the final word on the issues at hand. A reprint therefore required a detailed introduction bringing the reader up to speed with the current state of knowledge on document research into Auschwitz. The main text of the present book also fulfills this role, which therewith kills two birds with one stone.

If you cannot afford or don’t want to spend the money for this expensive reprint of Pressac’s magnum opus, you can always content yourself with following the many cross-references found in the present book to Pressac’s magnum opus by looking them up online or by borrowing a hard copy from a library.

Under no circumstances do I want you to blindly trust me or anyone else who speaks out on this sensitive issue. The potential of political and social abuse with this subject are greater than with any other. After all, Auschwitz cannot only be described as the epicenter of human suffering, but also as the epicenter of the “instrumentalization of our shame for contemporary purposes,” as German writer Martin Walser put it in his notorious 1998 speech.[4] With so much at stake, we all do well to make sure that we are on firm scientific ground.

To ensure this firm ground, many of the documents cited below are printed in facsimile. Many more can be found in the document appendices contained in the primary literature cited, most of which are available online as free PDF downloads. Hence, nothing stops you from finding out what the basis is of what the present book avers as knowledge.

Wimping out is not an option.

Germar Rudolf, Red Lion, PA

February 22, 2018

PS: As I write these lines, the reprint of Pressac’s magnum opus, which will include the contents of this book both in English and in German, is scheduled to appear in winter 2018/19 and will be available from Hanse Buchwerkstatt, Postfach 330404, D-28334 Bremen, Germany – unless the German censorship authorities have other plans… [Which they did. The owner of this publishing outlet was arrested in 2019, declared mentally insane, and disappeared from the face of the earth, for all I can tell. The company was dissolved by the German authorities. GR, May 2024.]

Who Was Jean-Claude Pressac?

Jean-Claude Pressac was a French pharmacist and amateur historian. In his youthful years, he was an admirer of Adolf Hitler. As such, he was bothered by the Holocaust, because it sullied Hitler’s reputation. He therefore became interested in arguments suggesting that the orthodox version of the Holocaust narrative was somewhat fishy. He realized quickly, though, that contesting, revising, or denying the Holocaust was very dangerous. Hence, he changed his approach. During the 1980s, he managed to gain the confidence of Serge and Beate Klarsfeld as well as the Auschwitz Museum, and to convince them that one has to defeat the revisionists or rather Holocaust deniers with their own weapons. The revisionists want to see solid evidence for the veracity of the orthodox narrative? Let them have it! Pressac promised to put a stop to the deniers’ games, at least regarding Auschwitz, by means of documents and technical arguments. He gained the support of the Klarsfelds and of the Auschwitz Museum, and got down to business forcefully: in 1989, the Klarsfelds published his first überwork: Auschwitz: Technique and Operation of the Gas Chambers. For the first time in history, this book made generally accessible a wide range of document reproductions concerning the history of the Auschwitz camp. Though of tremendous interest to many researchers in the world, only a very limited number of copies was printed and distributed to selected organizations and individuals. The book was never available for sale to the general public.

Four years later, Pressac upped the ante after having found further documents on Auschwitz in an archive in Moscow. While his first work became known only to connoisseurs of the subject, his second, a much more handy work in paperback format of just some 200 pages, became a bestseller: Les crématoires d’Auschwitz: La machinerie du meurtre de masse[5] – in plain English: The Crematories of Auschwitz: The Machinery of Mass Murder. Pressac himself mutated overnight to a darling of the mass media – a knight in shining armor who had slain the revisionist dragon! His book subsequently also appeared in a German,[6] Italian,[7] Norwegian,[8] Portuguese[9] and an English edition which, however, was heavily abridged and edited to conform to politically correct expectations.[10]

Pressac died in 2002 at the young age of 59, utterly forgotten by the media who had praised him as a hero merely eight years earlier. It is unclear why they ignored their former hero’s passing, but it may have had to do with Pressac’s increasingly skeptical statements about the orthodox Holocaust narrative.[11] Pressac’s second book, however, is today still hailed as a milestone of Auschwitz research. It is said to refute the deniers’ arguments with technical precision. In fact, due to its persisting relevance, the French publisher of Pressac’s second book issued a new edition in 2007.

This introduction aims at giving the reader a short summary of the research done after Pressac’s magnum opus was published in 1989. That research has greatly profited from the fact that, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, tens of thousands of documents in Czech, Polish and Russian archives have become accessible, enabling Auschwitz researchers to write a much more precise history of that most infamous of all German wartime camps. This means inevitably that not all of the claims Pressac wrote down in this book were confirmed by later research, while others could be substantiated with many more documents.

Claim and Reality

Already the title of Pressac’s 1989 book claims that its main focus is on the “Technique and Operation of the Gas Chambers” of Auschwitz. Beate and Serge Klarsfeld also highlight this claim by writing in their original preface to this book that it is a “scientific rebuttal of those who deny the gas chambers” (my emphasis). With that they refer to the fact that Pressac was a pharmacist by trade, and thus had some training in the exact sciences. Furthermore, just above the table of contents, we read that the reader will find in this book a “systematic study of the delousing and homicidal gas chambers […] of the former KL Auschwitz Birkenau, and an investigation of the remaining traces of criminal activity.”

What has to be expected from a work that scientifically and systematically describes the technique and operation of any device? Works of science and technology have different standards than those of history. While the latter can be narrative and highly conjectural in nature, science and technology have little room for this, if any.

The claims made in a scientific work must by necessity be supported either by source references to other scientific works, by experiments described in a way that they can be repeated by others, or by logical arguments. Particularly in the field of technology, logical arguments are most frequently based on mathematical reasonings.

Any book on the technique and operation of any device ought to be brimming with references to technical and scientific literature, should have some kind of mathematical reasoning as can be found in the field of engineering, and may even contain descriptions of any kind of experiments conducted.

Pressac’s present book does not contain any of it. His book is completely devoid of any references to anything. It has neither foot- nor endnotes, and not even a bibliography. As a matter of fact, if you carefully read all the text contained in it, you will find not a single reference to any scientific or technical literature in the text itself either. Nothing. Nada. Niente. Rien. Nichts.

So, how can a book that has none of the hallmarks of a book on technology be technological in nature? It simply can’t. At that point, if you are really interested in a thorough study of the technique and operation of the gas chambers, you are well advised to close this book and look elsewhere. And where would that be? Well, I will get to that at the end of this introduction. Let us now turn to Pressac’s first chapter on Zyklon B.

Zyklon B

The primary focus of any treatise on Zyklon B should be to first describe what the product is made of and what features it had. Next, a closer look into this product’s active ingredients would be warranted, which in this case is hydrogen cyanide (HCN). None of this can be found in Pressac’s 1989 book. It contains only a reference to the guideline for the use of Zyklon B for fumigations as it was published during the war by its distributor, the Degesch Company, and found in the files of the Health Authority of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in Prague. Not even that bit of background information is contained in Pressac’s elaboration, which otherwise contains no reference to any literature on either Zyklon B or HCN.

A large body of scientific literature on Zyklon B and fumigations with HCN was published primarily in Germany between the early 1920s and the end of World War Two. Instead of citing them here, I recommend consulting more-recent monographs on Zyklon B and its use which contain the pertinent references in their bibliographies.[12] Unless stated otherwise, the following information is taken from them.

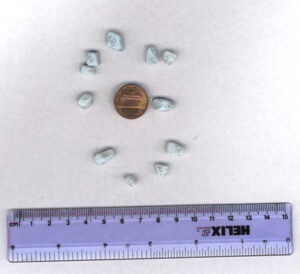

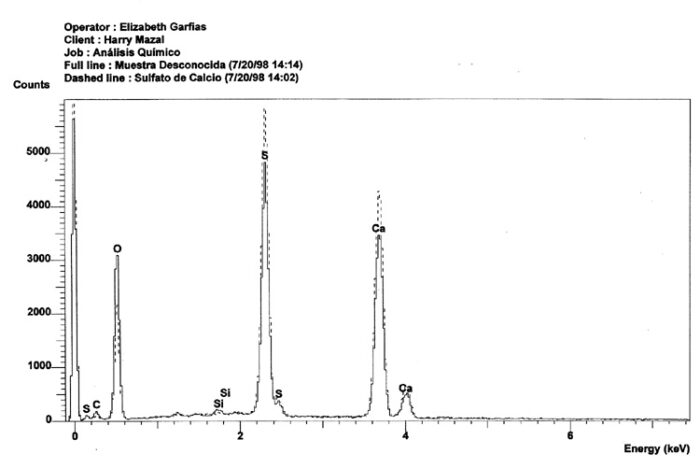

Zyklon B is liquid HCN soaked into some porous carrier material. Initially, diatomaceous earth was used (product name “Diagrieß”), but it compacted during transport, and was subsequently replaced by gypsum pellets (“Erco”). In addition, wood-fiber discs were also used, primarily for the U.S. market. A 1998 analysis of depleted Zyklon B pellets left behind by the Germans in Auschwitz at war’s end using a scanning electron microscope revealed that the carrier consisted of gypsum, see Illustrations 1 and 2.[13]

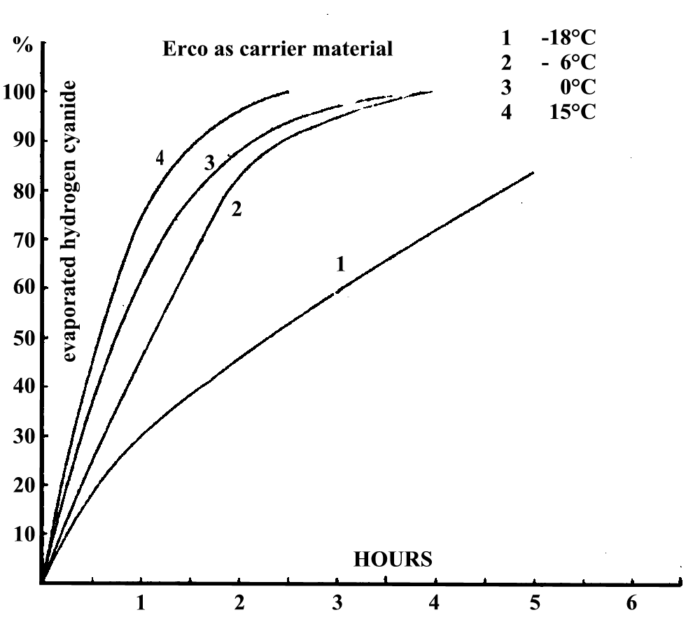

A 1942 publication by one of the scientists involved in optimizing Zyklon B gave detailed information about the speed with which HCN evaporates at which temperature from the gypsum pellets, provided the pellets are scattered out, and the ambient air’s relative humidity is low, see Ill. 3.[14]

On page 18, Pressac gives a long list of features of HCN without indicating where he got this data from, which is typical for him. (Unless stated otherwise, all page numbers subsequently given are from Pressac’s 1989 book.)

The chemical and physical properties of HCN are well established,[15] and the physiological effects of hydrogen cyanide on insects as well as mammals, humans included, are well-researched. Every toxicological handbook contains an entry, including those that predate World War Two.[16] Hence, Pressac’s claim on page 184 that “the lethal dose for humans was not known” to the SS seems far-fetched. However, a 1976 study by McNamara revealed that many, if not all of these toxicological handbooks took their data regarding the susceptibility of humans to gaseous HCN directly or indirectly from a German study of 1919, which reported the effects of gaseous HCN on rabbits.[17] Actual experiments with a human volunteer showed that the concentration listed by toxicological literature and repeated by Pressac as “immediately mortal” – 300 mg/m³ – is not immediately mortal for humans at all. While McNamara had only very limited data to rely on, American researcher Scott Christianson tapped into the precisely recorded data of hundreds of cases where humans were actually killed with HCN: executions of death penalties in the United States using HCN gas chambers. That data showed that it took on average 9.3 minutes to kill humans with a concentration of some 3,000 mg/m³ – ten time the above value! – while the longest execution with that kind of concentration took 18 minutes.[18] Hence, humans are actually quite resilient to gaseous HCN, even more so than Pressac assumed.

Pressac asserts that “By far the greater part (over 95 percent) [of Zyklon B delivered to Auschwitz] was destined for delousing […] while only a very small part (less than 5 percent) had been used for homicidal gassings” (p. 15). He doesn’t back up his data with anything. In fact, since it is not known how many times Zyklon B was used with exactly what amount in the camp’s various fumigation chambers, and because it is also unknown how often the many other buildings of that camp were fumigated for pest control with how much Zyklon B per event, there is no way of pinpointing the percentage of delivered Zyklon B used for innocuous purposes. Auschwitz, with its hundreds of prisoners’ accommodation blocks, had enough volume to perfectly explain the actual Zyklon B deliveries as needed for fumigations.[19] Hence, the large quantities of Zyklon B delivered to the camp do not prove anything by themselves.

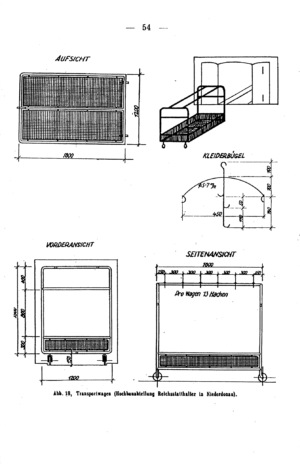

Disinfestation Devices

(For the second page, see the next illustration; Source: Russian War Archives, 502-1-333, pp. 7f.)

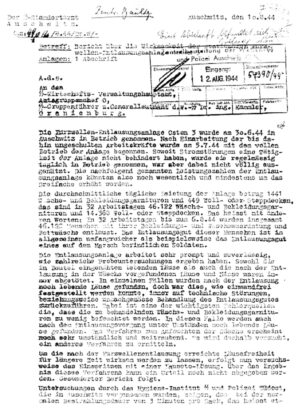

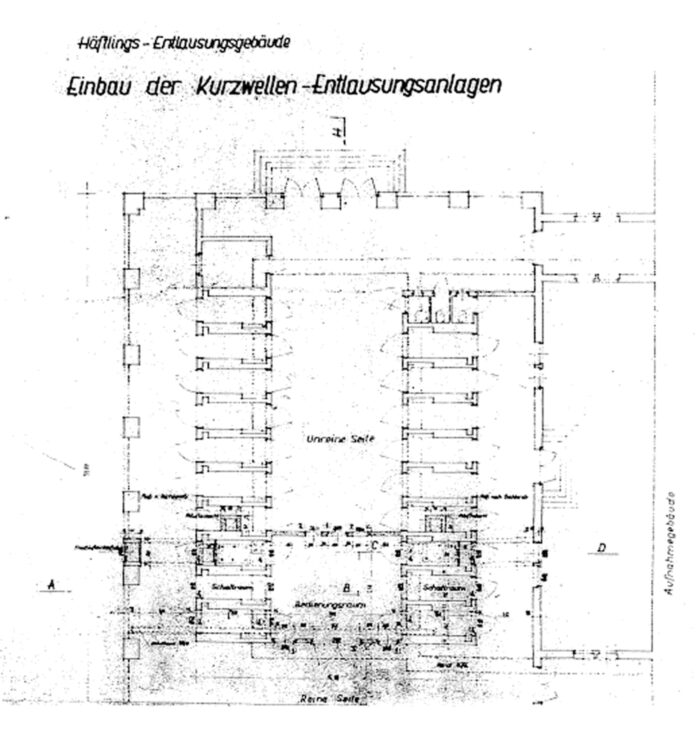

About the 19 Zyklon-B fumigation chambers originally planned for the reception building at the Auschwitz Main Camp, Pressac writes that its present state “makes it impossible to reconstruct the techniques employed” (p. 31). The reason for this is that the plan to install these chambers was abandoned in 1943 and replaced with a microwave disinfestation facility, the first of its kind in history. Siemens started developing the device in 1936. It was originally slated for use on garments of German soldiers. A shift of priorities occurred in early 1943, however. At that point, the typhus epidemic which had broken out at the Auschwitz Camp in spring of 1942 was still not under control, and many tens of thousands of prisoners had succumbed to it already. To preserve this slave-labor resource for the pivotal war industries of the Auschwitz area, the German authorities decided to use the most modern technique at their disposal to stamp out that epidemic for good. Due to air raids on Berlin damaging the local Siemens factories, however, the actual deployment of the device was delayed until spring of 1944. It went into operation on June 30, 1944, and proved to be sensationally efficient and effective.[20] Here are a few excerpts of the text of Illustration 4 in translation, a report written by Auschwitz garrison physician Dr. Eduard Wirths on August 10, 1944:

“Report about the efficacy of the stationary shortwave delousing device

The shortwave delousing device Osten 3 was taken into operation at Auschwitz on June 30, 1944. After training the so-far unskilled employees, full operations of the device started on July 5, 1944. Unless interrupted by blackouts, it was operated on a daily basis, but not always at full load. The delousing device’s performance data listed hereafter can be increase at least threefold.

The device’s average daily performance was 1441 sets of clothing and 449 blankets or comforters, which amounts to 46,122 sets of laundry and 14,368 blankets or comforters within 32 business days. In other words: Within 32 business days, until Aug. 6, 1944, all in all 46,122 people and their laundry and bed linens were deloused. The belongings to be deloused which these people have are usually more voluminous than for instance the stuff of a soldier in the field.

The delousing device operates very swiftly and reliably, as many test runs have shown […].

In order to extend the time during which the items are free of lice after the shortwave delousing, they are now impregnated with a Lauseto [DDT] solution on a trial basis […].

Tests conducted at Auschwitz by the Hygiene Institute of the SS and Police Southeast show that a complete sterilization of all tested staphylococci, typhus and diphtheria samples was achieved during an irradiation of 3 minutes per sack, or 45 seconds per individual item. […]”

Another fact unknown to Pressac was that DDT showed up at Auschwitz for the first time in 1944. It was produced under license from the Swiss chemical company Geigy, with the German name “Lauseto” (for Lausetod, louse death).[21] The Auschwitz Camp received 9 metric tons of it in April 1944, 15 tons in August, and 2 tons in October of that year.[22]

Since Pressac’s book is about the technique and operation of gas chambers, it would have behooved the author to explain to the reader in technical detail the technique and operation of both the U.S. execution gas chambers, mentioned by him only in passing on page 22, and of the professionally designed German disinfestation chambers.

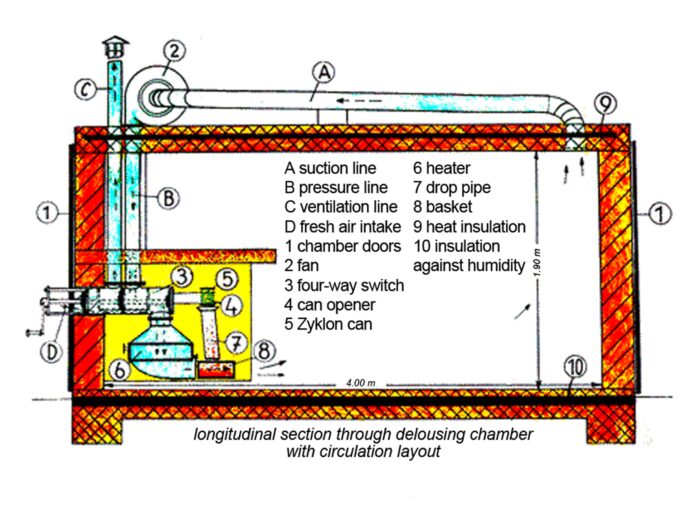

The U.S. execution gas chambers are the only type of homicidal gas chambers about which we have a complete documentation from their inception, of their design, construction and operation up to their decommissioning. By researching them, Pressac would have realized that some of his claims, for instance about the speed of executions, are unrealistic. Explaining in detail the Zyklon-B fumigation chambers which the German Auschwitz camp authorities had planned to install in their reception building would have led to numerous epiphanies. First of all, the Auschwitz camp authorities were informed about that circulation technology, as it was called, already on July 1, 1941, through a letter written to them by one of the distributors of Zyklon B.[23] It included the reprint of a technical paper describing the system.[24] That paper’s description of the system (see Illustration 6) served as a pattern for the design of the 19 planned Zyklon-B gas chambers at the reception building.[25] There are three main insights we can gain from studying these chambers.

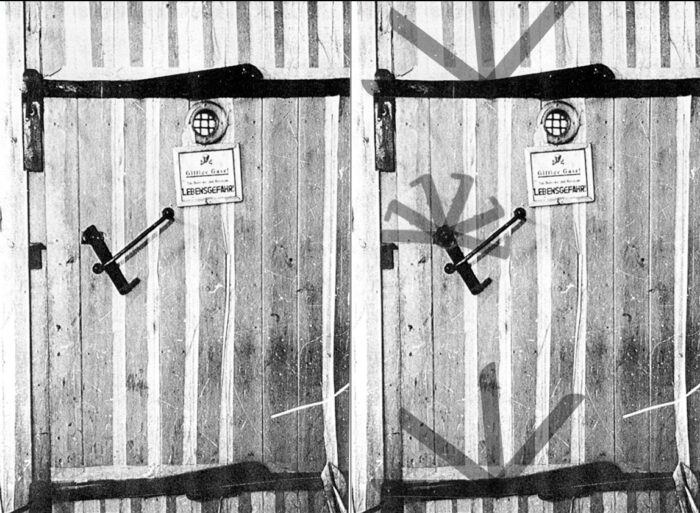

The first is that those chambers were by default equipped with sturdy steel doors, see Illustration 7 for the Degesch circulation devices still visible at Dachau.

Second, we need to be aware that the claimed swift executions require a fast rise in poison gas concentration everywhere in the chamber. The Degesch circulation device accomplished this in two ways: first by blowing warm air across the Zyklon B pellets, and then by channeling the air for the fan through a pipe from the other end of the chamber, thus circulating the air, hence spreading the fumes evenly throughout the chamber.

Third and finally, in order to achieve a relatively short ventilation time of only an hour or so, the ventilation system recommended for these devices had 72 air exchanges per hour.[26]

I’ll get back to these issues when addressing doors, introduction devices and the ventilation system, all of which are mentioned by Pressac without any technical context.

The article sent to the Auschwitz authorities does show that not only German experts in this field knew how to build efficient gas chambers, but the Auschwitz camp authorities knew this as well. To top it off, in his already mentioned study, Scott Christianson showed that German chemical companies lobbied for the introduction of hydrogen cyanide gas chambers for the execution of death row inmates in the U.S. in the 1920s and 1930s. Hence, the German specialists also knew very well where to find additional information and empirical data, which they could have, should have, would have used to build their very own homicidal gas chambers. There is, however, no trace of any contact between German and U.S. specialist in this regard in the extant documentation.

Gastight Doors, General Remarks

Many gastight doors were built by Auschwitz inmates in the local workshop. Pressac shows a number of them on pages 46, 48-50, 232, 425 and 486. These doors were constructed of wooden boards held together with iron bands. Technically speaking, they could not have been gastight. In fact, no wooden door can ever be truly gastight, in particular if it consists of several individual boards. Nevertheless, the camp authorities referred to these doors as “gastight.”

Some of these doors were equipped with a peephole covered on the inside by a protective metal grid, see Illustration 10. The peephole was required by German law for fumigation rooms without a window. It stipulated that any person entering such a chamber had to be observed by another person from the outside, who needed to wear a gas mask as well and had to have a first-aid kit at hand. This way he could swiftly intervene in case of an emergency, for example, caused by a leaking or improperly donned gas mask.[27]

A protective grid on the inside of a fumigation room was also needed, because clothes were put into those chambers on metal racks, see those used in the Auschwitz “Zentralsauna” as shown by Pressac himself (pp. 84f.). Similar clothes racks were also used in Zyklon-B fumigation chambers (See Illustration 8).[28] When wheeled in and out of the chamber, in particular when the door was being closed behind them, these racks could accidentally knock against any non-protected peephole’s glass, cracking it in the process.

The term “gastight door” is used by Pressac frequently, because it can be found in many documents. Yet it always refers to this wooden type of doors. The vast documentation of the Auschwitz Central Construction Office does not contain any trace of a real gastight door, one made of steel as shown in Illustration 7. As a matter of fact, an estimate for such doors was indeed requested for the initially planned 19 circulation fumigation chambers inside the reception building,[29] but since that project was cancelled in 1943, the doors were apparently never delivered, as results from an inquiry by the vendor of these doors in November 1944, asking whether the camp was still interested in the doors’ delivery.[30]

Even the doors used to seal the SS air-raid shelter in Crematorium I were made of a wooden frame with a nailed-upon, hence perforated sheet-iron cover, see Illustration 9.

Could the wooden doors, made by the inmates in their workshop, have been used to seal homicidal gas chambers? Illustrations 10a&b show a typical Auschwitz gastight door as shown by Pressac on page 49. In Illustration 10b I have shown the range of motion of the three latches that could be used to lock that door. This particular door was used for a disinfestation chamber. The cracks between the boards were “sealed” with felt strip to reduce any poison-gas leakage. It goes without saying that such felt strips may slow down a draft, but they can never be “gastight.”

The main challenge would not have been to keep the door from leaking, but to keep hundreds or even a thousand and more victims, who were locked up inside and who most certainly were panicking, from forcing open a door like this. After all, any execution-chamber door had to open to the outside, because many victims would die right in front of the door, blocking it from the inside.

Wood isn’t the sturdiest material, and the iron bands used for the hinges and latches would bend sooner or later when forced by a massive crowd. For the SS, it would have been reckless, to say the least, to use such doors for homicidal mass-slaughter rooms.

The Blue-Wall Phenomenon

On page 53, Pressac briefly discusses the “blue-wall phenomenon,” which, according to him, “permits the immediate distinction on sight between delousing and homicidal gas chambers.” While Zyklon-B delousing chambers developed a more or less intense blue wall discoloration, caused by Prussian Blue (iron cyanide), the claimed homicidal gas chambers did not. Pressac attributes the difference between both types of facilities mainly to three factors:

- While lice need HCN concentrations of 5 g/m³, a concentration of 0.3 g/m³ is immediately fatal for man. Pressac claims that “the quantity poured into the homicidal gas chambers was forty times the lethal dose (12 g/m³) which killed without fail one thousand people in less than five minutes.” He does not prove this latter claim.

- While the delousing chamber walls were exposed to the gas for 12 to 18 hours a day (an unproven conjecture), the homicidal gas chamber walls had an exposure time of not more than 10 minutes per day (another unsupported conjecture).

- While the delousing chambers were heated to 30°C, thus assisting chemical reactions in the wall, the homicidal gas chambers were “without additional heat.”

Pressac also states that the formation of the blue discolorations appeared “under the influence of various physico-chemical factors which have not been studied.” In the meantime, a number of studies have been found or conducted in this regard, starting with a case of a Bavarian church which was fumigated with Zyklon B in 1976, after it had just been renovated. It subsequently developed the “blue-wall phenomenon.”[31] Two more chemists published investigations about this phenomenon, with a focus on Auschwitz.[32] The gist of these studies is as follows:

- The reactions involved require an alkaline medium and a minimum amount of moisture inside the wall.

- While cool walls in unheated underground rooms have a high moisture content (such as the underground morgues of Crematoria II & III at Auschwitz-Birkenau, some of which are said to have served as homicidal gas chambers), heated above-ground rooms, such as the fumigation chambers, have a low moisture content.

- While the walls, floors and ceilings of the morgues of Crematoria II & III at Auschwitz-Birkenau were built using plaster, mortar and concrete with high contents of cement, keeping them alkaline for years, the mortar and plaster used for the Auschwitz fumigation chambers (particularly Buildings 5a and 5b) were poor in cement and rich in lime. Hence, they stayed alkaline for a much shorter period of time.

Already in 1929, a German experimental series showed that moist walls absorb up to 8 times more HCN than dry walls, and that alkaline masonry absorbs 25-times more HCN than non-alkaline masonry. Alkaline masonry also releases the gas much slower during ventilation.[33] In addition to alkalinity, this greater tendency to absorb and bind HCN may also be caused by the different chemical and physical features of cement compared to lime mortar. The cement’s huge inner microscopic surface supports chemical reactions of the kind under scrutiny in more than one way. We won’t go into more details here, though. The interested reader may consult the works cited.

It is thus evident that the physical and chemical features of the claimed homicidal underground gas chambers inside the Crematoria II & III would have had a much higher propensity to form the blue pigment in question, quite contrary to Pressac’s claim.

Pressac’s claim of a swift execution in the homicidal gassings at Auschwitz is based on two premises:

- Zyklon B releases its HCN fast.

- Humans are as susceptible to gaseous HCN as claimed in toxicological literature.

| Illustration 11: 442 pages of thorough chemical investigation into the chemistry of Auschwitz. The book is available as a free PDF download and is accompanied by a documentary at www.HolocaustHandbooks.com. |

As mentioned earlier, both assumptions are wrong. Despite the fact that victims of gas chamber executions in the U.S. are instantly exposed to the full concentration of the poison, which at 3,200 ppm is more than ten times higher than the instantly lethal concentration given in toxicological literature, it still takes up to 18 minutes to kill all victims.[34]

Finally, Pressac’s claim about brief ventilation times is also flawed, which I will discuss later when addressing ventilation systems.

This introduction is not the place to discuss all the issues involved that would allow us to conclude with certainty what all the facts are regarding this blue-wall phenomenon. For this, the interested reader can consult the literature cited and watch the documentary mentioned in Illustration 11. These brief elaborations merely serve to emphasize that Pressac jumped to premature conclusions without backing up any of his claims. As a matter of fact, it looks like he didn’t even try to investigate the matter.

Claiming that the lack of blue stains on their walls is a hallmark of homicidal gas chambers is puerile at best, because if that were so, basically all buildings in the world, lacking blue wall stains, would meet that criterion. The lack of evidence, however, cannot prove a claim; it actually refutes it.

* * *

The complete book can be read and downloaded free of charge at www.holocausthandbooks.com/book/auschwitz-technique-and-operation-of-the-gas-chambers/

Endnotes

| [1] | He said this about Crematorium II in Auschwitz-Birkenau, where most victims are said to have perished: some 500,000; Errol Morris, Mr. Death: The Rise and Fall of Fred A. Leuchter, Jr., Fourth Floor Productions, May 12, 1999; VHS: Universal Studios 2001; DVD: Lions Gate Home Entertainment, 2003; first screened on Jan. 27, 1999 during the Sundance Film Festivals at Park City (Utah); https://codoh.com/library/document/mr-death-rise-and-fall-fred-leuchter-jr/, starting at 25 min. 15 sec.] |

| [2] | Jacques Baynac, “Faute de documents probants sur les chambres à gaz, les historiens esquivent le débat”, Le Nouveau Quotidien, Sept. 3, 1996, p. 14.] |

| [3] | See the list of supporters in Pressac’s 1989 book on page 8.] |

| [4] | Martin Walser, “Erfahrungen beim Verfassen einer Sonntagsrede”, acceptance speech for the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade (Friedenspreises des Deutschen Buchhandels), Frankfurt, October 11, 1998; www.friedenspreis-des-deutschen-buchhandels.de/sixcms/media.php/1290/1998_walser_mit_nachtrag_2017.pdf.] |

| [5] | Jean-Claude Pressac, Les crématoires d’Auschwitz: La machinerie du meurtre de masse, CNRS éditions, Paris 1993, viii-156 pages plus a 48-page section with illustrations.] |

| [6] | J.-C. Pressac, Die Krematorien von Auschwitz: Die Technik des Massenmordes, Piper Verlag, Munich/Zürich 1994, xviii-211 pages.] |

| [7] | J.-C. Pressac, Le macchine dello sterminio: Auschwitz 1941-1945. Feltrinelli, Milan 1994.] |

| [8] | J.-C. Pressac, Krematoriene i Auschwitz: Massedrapets maskineri, Aventura, Oslo 1994.] |

| [9] | J.-C. Pressac, Os crematórios de Auschwitz: A maquinaria do assassínio em massa, Ed. Notícias, Lisbon 1999.] |

| [10] | J.-C. Pressac, Robert J. Van Pelt, “The Machinery of Mass Murder at Auschwitz,” in: Israel Gutman, Michael Berenbaum (eds.), Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp, Indiana University Press, Indianapolis 1994, pp. 183-245.] |

| [11] | Particularly in his interview with Valéry Igounet, Histoire du négationnisme en France. Éditions du Seuil, Paris 2000, pp. 613-652.] |

| [12] | Jürgen Kalthoff, Martin Werner, Die Händler des Zyklon B: Tesch & Stabenow. Eine Firmengeschichte zwischen Hamburg und Auschwitz, VSA-Verl., Hamburg 1998; Hans Hunger, Antje Tietz, Zyklon B, Books On Demand, Norderstedt 2007; Horst Leipprand, Das Handelsprodukt Zyklon B: Eigenschaften, Produktion, Verkauf, Handhabung, GRIN Verlag, Munich 2008; Germar Rudolf, The Chemistry of Auschwitz: The Technology and Toxicology of Zyklon B and the Gas Chambers – A Crime-Scene Investigation, Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield 2017.] |

| [13] | Harry W. Mazal, “Zyklon-B: A Brief Report on the Physical Structure and Composition,” http://phdn.org/archives/holocaust-history.org/auschwitz/zyklonb/ (undated; 1998).] |

| [14] | Richard Irmscher, “Nochmals: ‘Die Einsatzfähigkeit der Blausäure bei tiefen Temperaturen’,” Zeitschrift für hygienische Zoologie und Schädlingsbekämpfung, 34 (1942), pp. 35f.] |

| [15] | See the entries in William Braker, Allen L. Mossman, Matheson Gas Data Book, Matheson Gas Products, East Rutherford 1971; Robert C. Weast (ed.), Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 66th ed., CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida 1986, or any newer edition.] |

| [16] | Most prominent Ferdinand Flury, Franz Zernik, Schädliche Gase, Dämpfe, Nebel, Rauch- und Staubarten, Springer, Berlin 1931.] |

| [17] | B. S. McNamara, The Toxicity of Hydrocyanic Acid Vapors in Man, Edgewood Arsenal Technical Report EB-TR-76023, Department of the Army, Headquarters, Edgewood Arsenal, Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland, August 1976; www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA028501; see his traced-back line of “Chinese whisper” citation in toxicological literature there.] |

| [18] | Scott Christianson, The Last Gasp: The Rise and Fall of the American Gas Chamber, University of California Press, Berkeley, Cal., 2010, pp. 81f., 85, 99f., 106, 111f., 114, 116f., 180f., 189, 199, 209-211, 214, 216, 223, 229; an average of 9.3 min from 113 cases is reported on p. 220.] |

| [19] | For a calculation of this see Carlo Mattogno, Deliveries of Coke, Wood and Zyklon B to Auschwitz: Neither Proof Nor Trace for the Holocaust, Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield, 2021, pp. 82f.] |

| [20] | Hans Jürgen Nowak, “Kurzwellen-Entlausungsanlagen in Auschwitz,” Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung, 2(2) (1998), pp. 87-105; Hans Lamker, “Die Kurzwellen-Entlausungsanlagen in Auschwitz, Teil 2,” Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung, 2(4) (1998), pp. 261-272; Mark Weber, “High Frequency Delousing Facilities at Auschwitz,” The Journal of Historical Review, 18(3) (1999), pp. 4-12.] |

| [21] | Paul Weindling, Epidemics and Genocide in Eastern Europe, 1890-1945, Oxford University Press, Oxford/New York 2000, p. 380.] |

| [22] | Piotr Setkiewicz, “Zaopatrzenie materiałowe krematoriów i komór gazowych Auschwitz: koks, drewno, cyklon,” in: Studia nad dziejami obozów konzentracyjnych w okupowanej Polsce, Państwowe Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkenau, Auschwitz 2011, pp. 46-74, here p. 72.] |

| [23] | Letter by Heerdt-Lingler to SS-Neubauleitung, July 1, 1941. Russian War Archives, 502-1-332, p. 86.] |

| [24] | Gerhard Peters, Ernst Wüstinger, “Entlausung mit Zyklon-Blausäure in Kreislauf-Begasungskammern. Sach-Entlausung in Blausäure-Kammern,” Zeitschrift für hygienische Zoologie und Schädlingsbekämpfung, 32 (10/11) (1940), pp. 191-196.] |

| [25] | See the blueprint of June 24, 1944, Illustration 61, in the appendix to this introduction.] |

| [26] | Franz Puntigam, Hermann Breymesser, Erich Bernfus, Blausäuregaskammern zur Fleckfieberabwehr, special edition by the Reichsarbeitsblatt, Berlin 1943, p. 50.] |

| [27] | Mauthausen Museum Archives, M 9a/1; reproduced in: Carlo Mattogno, “The ‘Gas Testers’ of Auschwitz, Testing for Zyklon B Gas Residues · Documents – Missed and Misunderstood,” The Revisionist, 2(2) (2004), pp. 140-154; here p. 151.] |

| [28] | See Illustration 18 in Franz Puntigam et al., op. cit. (note 22), p. 54.] |

| [29] | Offer by the Berninghaus Company of July 9, 1942, Russian War Archives, 502-1-354, p. 8.] |

| [30] | Ibid., 502-1-333, p. 2; letter by the Berninghaus Company of November 22, 1944.] |

| [31] | Helmut Weber, “Holzschutz durch Blausäure-Begasung. Blaufärbung von Kalkzement-Innenverputz,” in: Günter Zimmermann (ed.), Bauschäden Sammlung, Vol. 4, Forum-Verlag, Stuttgart 1981, pp. 120f.] |

| [32] | Richard J. Green, “Leuchter, Rudolf and the Iron Blues,” 1998, idem, “The Chemistry of Auschwitz,” 1998; see www.phdn.org/archives/holocaust-history.org/auschwitz/chemistry; also G. Rudolf, The Chemistry of Auschwitz, op. cit. (note 8).] |

| [33] | L. Schwarz, Walter Deckert, “Experimentelle Untersuchungen bei Blausäureausgasungen,” Zeitschrift für Hygiene und Infektionskrankheiten, 109 (1929), pp. 201-212.] |

| [34] | For a swift test gassing with rabbits, showing the instant exposure to the gas, see the BBC documentary 14 Days in May, 1987; www.dailymotion.com/video/x20z7qm.] |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, Vol. 11, No. 1 (2019); ; excerpt from Germar Rudolf, Auschwitz: Technique and Operation of the Gas Chambers. An Introduction and Update to Jean-Claude Pressac’s Magnum Opus, Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield, UK, 2019

Other contributors to this document:

Editor’s comments: