Capitalism in the New Russia

Daniel W. Michaels is a retired Defense Department analyst who lives in Washington, DC. After graduating in 1954 from Columbia University (Phi Beta Kappa), he studied in Tübingen, Germany (1957), with a Fulbright scholarship.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991–1992, and the end of the centrally controlled “command economy,” a new class of wealthy private capitalists with close government connections has emerged in Russia. The new ruling clique that has replaced the Soviet-era “nomenklatura” is widely referred to by the American-origin term “istablishment.”

At the same time, life for most Russians has not improved. The great majority still struggles to survive, sometimes below the subsistence level. Industrial and agricultural production have fallen 50 percent in recent years, and millions are not paid their paltry salaries on time. Because most people lack hard currency to buy anything but essentials, consumer goods are generally accessible only to successful speculators, the mafia, and higher government officials. For the average Russian, and especially the elderly, life is not just impoverished, it is becoming desperate. [See: “Nationalist Sentiment Widespread, Growing in Former Soviet Union,” Sept.–Oct. 1995 Journal, pp. 8–10.]

Russians pin much of the blame for this catastrophe on the ineffectual government of President Boris Yeltsin and his Prime Minister, Viktor Chernomyrdin. In a public statement issued last December, a group of prominent Russian intellectuals spoke out on the crisis in their homeland:

The catastrophe has run its course. The economic policy of Yeltsin’s and Chernomyrdin’s aides has made a small section of the former communist nomenklatura and of the “new Russians” unbelievably rich, plunged most of the nation’s industry into paralysis, and reduced the majority of the population to poverty. As far as property ownership is concerned, the gap between the rich and poor is much deeper now than that which led to the [1917] October [Bolshevik] Revolution.

Corrupt Businessmen Flourish

During the Soviet era, centralized Communist Party rule ensured that economic activity, however inefficient, was at least fairly predictable, with a more or less reliable work force. Although living standards were low, this “banana republic with rockets” was stable in the way that a prison is.

Now lawlessness prevails in Russia, with business life functioning at a level similar to that of Al Capone’s Chicago. There is no effective system of laws to ensure the fair and orderly operation of business, banking, finance, insurance, stock trading, and so forth, and existing laws are neither consistently nor impartially enforced. Lawlessness and excess are more often rewarded than punished, and people have little protection against fraud by the new criminal class.

Russia specialist Richard F. Staar, a Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, reports in The Washington Times (Nov. 27, 1996):

In his book, Comrade Criminal, Stephen Handelman discussed connections between the already then well-established mafia underworld and corrupt bureaucrats, a relationship that apparently now has reached into the Kremlin itself. According to former Russian Social Security Minister Ella A. Pamfilova, a cynical redistribution of property currently is taking place. In her words, “The nature of the ruling class has not changed … It is the same old corrupt, elitist, nomenklatura-bureaucratic swamp.”

What is changing involves the national economy, half of which already has fallen under mob control, according to Security Council Secretary Ivan Rybkin. Former Director of the CIA, Robert M. Gates estimated earlier this year that two-thirds of all commercial institutions, some 400 banks (those in Moscow already control 80 percent of the country’s finances), several dozen stock exchanges, and 150 large government enterprises are controlled by the mob.

A recent Russian periodical revealed that about 40 percent of the Gross Domestic Product is in the hands of organized crime, mow merged with corrupt official and businessmen.

One prominent scandal involves a businessman named Anatoly Aronov, who is under indictment for establishing some 500 fraudulent paper corporations. By cleverly manipulating the slipshod Russian banking system, and taking full advantage of the uncontrolled market economy, the vulnerability of inexperienced Russians, and the general climate, Aronov created a phantom business empire. After establishing the paper companies as “legal entities,” Aronov then sold them at great profit to unwary Russians.

The disorder of Russia’s banking system has been described in a November 12 , 1996, article by Rafail Kashlinksy in Vestnik, a Russian-language magazine published in the US. Of the more than 2,700 banks in Russia at the beginning of 1995, it reports, by the end of that year the Central Bank of Russia was obliged to revoke licenses of 225 of these, while more than 800 banks finished the year with large losses. Another 500 banks, including some of the largest (such as the Moscow Interregional Commercial Bank), were near bankruptcy by mid-1996.

Woodrow Wilson Center analyst J. Johnson, dispatched to Russia to evaluate the situation, found four main reasons for the country’s banking crisis: a lack of professionally trained personnel; credit policy shortcomings; the monopolistic right of the quasi-government Sberbank to intervene in many instances as a government agent, giving it an unfair advantage in attracting clients and gaining access to useful information; and, the role of organized crime, which forces some bankers to divert time and resources to protecting themselves.

Crucial to the transition to a market economy is transferring business enterprises from state to private ownership. But this process has been ridden with abuse and corruption. Most of the oligarchs of Russia’s new business elite are not self-made men. On the contrary, they were simply given control of (state-owned) oil, gas, automobile, banking and other enterprises – essentially as gifts of the Yeltsin government to whom, of course, the newly-wealthy (and often youthful) businessmen are indebted.

Through the office of 35-year-old Deputy Prime Minister Alfred Kokh, the government assigns most of the enterprises to friends or supporters of Yeltsin and his administration, who, as new corporate CEOs, show their appreciation by supporting the government with money and favorable media coverage.

In an illustrative case, the Yeltsin government transferred 80 percent ownership shares in Russia’s second largest oil company (formerly the state-owned Yukos company) to Mikhail Khodorosvsky, 33-year-old former head of the Communist Youth League and founder of the Menatep Bank. In return, Khodorosvsky turned over $168 million to the Yeltsin administration. (Newsweek, March 17, 1997).

The Russian word for privatization, “privatizatsiya,” is routinely and cynically rendered by Russians as “prikhvatizatsiya,” meaning “grabbing,” or “piratizatsiya,” meaning “pirating.”

Russia’s most successful new businessmen, the so-called “Big Seven” (and their main business holdings), are: Rem Vyakhirev (Gazprom), Boris Berezovsky (Logovaz), Vladimir Gusinsky (Most Bank), Vaghit Alekperov (Lukoil), Alexander Smolensky (Stolichnyy Bank), Mikhail Khodorkovsky (Rosprom), and Andrey Kazmin (Sberbank).

These seven men alone, experts believe, control virtually half of the companies whose shares are rated the highest at the national stock market. Other prominent members of the new business elite include Vladimir Potanin (Oneksim Bank), Vladimir Vinogradov (Inkombank), Anatoly Dyakov (RAO EES Rossii), Yakov Dubenetsky (Promstroybank), and Petr Aven (Alpha Bank). (Izvestia [Moscow], Jan. 5, 1997).

It is estimated that more than $60 billion has already found its way from Russia into Swiss banks, reports the London Financial Times. Of this amount, $10 billion is believed to be mafia money. This same paper also reports (Feb. 14) that criminal groups control some 41,000 companies in Russia, half the banks and 80 percent of the joint ventures.

Conscious of the precarious foundation of the Russian economy, foreign businessmen are understandably apprehensive about investing in this treacherous environment.

To deal with the situation, some steps have been taken. Russia’s Federation (national) government is attempting to introduce a Civil Code based on that of The Netherlands, while American advisors have written statutes to govern operations of joint stock companies. But because Russia’s historical experience has little in common with either the Dutch or the American, it is doubtful that these administrative imports will prove very effective.

Previous Russian experience with capitalism – from the mid 19th-century to the 1917 revolution, and during the short-lived “New Economic Policy” (NEP) period (1921–1928) – is scant help in establishing a modern free market economy. While it is true that industrial development advanced rapidly in Russia in the decades immediately preceding the outbreak of the First World War (1914), it is also true that the plight of the emerging working class was often miserable – a source of unrest that contributed to the revolutionary upheavals of 1905 and 1917. And the NEP experience was too brief and limited in scope to serve as a useful model. (The corruption of “Nepmen” incidentally provided abundant source material for Soviet satirists.)

Unless and until drastic changes are made, a healthy market economy cannot develop. These changes must include: a comprehensive code of business and banking law to protect investments, a credible judicial system to rigorously and impartially enforce the laws, a sweeping purge of corrupt police personnel, a country-wide crackdown on crime and corruption, and a stable monetary policy.

What is particularly tragic about Russia’s economic calamity is that this vast land has such potential. In addition to a generally capable and well-trained managerial and working population, Russia is rich in natural resources, including oil, iron ore, gold and timber. Properly administered, this could be a very prosperous country.

Political Corruption

Without honest and effective political leadership, though, prosperity for the great majority will remain an elusive hope. Given its record so far, the government of President Boris Yeltsin can hardly be expected to provide the needed guidance and direction.

During last year’s election Russian banks directed substantial resources to favored political candidates. While some backed the national-patriotic and Communist candidates, those who supported Yeltsin were rewarded. Thus, when Yeltsin formed his new post-election administration he appointed Vladimir Potanin, the 35-year-old president and co-founder of the country’s biggest private bank, Oneksim Bank, as first vice premier for economics.

Because Yeltsin owes his July 1996 reelection victory in large measure to the financial and media support of Russia’s new plutocrats, his government is widely disdained as an instrument of alien interests. Although many former Communist Party officials (including Yeltsin himself), as well as former KGB functionaries, continue to occupy high-level positions in Russia, the Yeltsin administration is widely regarded as an American-controlled and -directed “internationalist” regime. Yeltsin’s chief of staff and primary economic advisor, Anatoly Chubais (age 41), is viewed as a US stooge at best, and a CIA agent at worst.

Opposing Yeltsin and his adherents is a diverse array of nationalists: national communists, national socialists, and national capitalists. In general, they call for a healthy, nationally-conscious Russian folk capable of defending and restoring the nation’s dangerously dissipated ethnic and cultural character. [See: E. Zündel, “My Impressions of the New Russia,” Sept.–Oct. 1995 Journal, pp. 2–8.]

Easily the most popular political figure in Russia today is General Aleksandr Lebed, a decorated Afghan war hero and the broker of peace in Chechnya. Even his critics concede his basic honesty. “Ordinary Russians are as far from the real levers of power today as they were during Soviet Communist Party rule,” says Lebed. Half the nation’s economy, he adds, is controlled by “a small group of banks and financial-industrial groups, while the other half is controlled by criminal clans.”

To protect their own corrupt business empires, the new plutocrats around Yeltsin will predictably do everything in their power to keep Lebed, or any authentically Russian figure, regardless of popularity, from taking power.

Not surprisingly, Lebed complains that he now has become invisible in the pages and programs controlled by the major media barons. In addition, no major bank will help finance him for fear of Kremlin retribution. (Newsweek, March 17, 1997.)

Prime Minister Chernomyrdin and Communist Party leader Gennady Zyuganov reportedly (Washington Times, Feb. 8) have discussed forming a political alliance to keep Lebed out of power if Yeltsin dies in office. Chernomyrdin and some of his backers, among them Moscow’s major bankers, are said to fear possible arrest as part of a nationwide campaign against corruption demanded by Lebed. (Chernomyrdin and Zyuganov have been personal friends since they served together six years ago on the Central Committee of the former Soviet Communist Party.)

To deal with the growing nationalist sentiment, authorities in Moscow are considering steps to crack down on its most extreme manifestations. Moscow’s Municipal Duma is considering a measure that prohibits the display or political use of symbols associated with Third Reich on the grounds that they disrupt the general order, incite to violence in a multinational society, and foster political extremism. Also forbidden would be the wearing of uniforms, displaying swastikas, and the use of the Roman (Hitler) salute as a greeting.

Zionist Kingmaker Berezovsky

Personifying Russia’s new ruling class is Boris Abramovich Berezovsky, a Jewish business magnate, media mogul, and high-ranking government official whom US News & World Report calls (Jan. 13, 1997) “the most influential new capitalist tycoon in Russia.” His business empire includes a bank, one of the few national television channels, oil concerns and automobile dealerships. (Forward [New York], Nov. 22, 1996.) After taking advantage of high-level political connections to quickly amass enormous wealth, Berezovsky provided large sums and favorable media coverage to insure the re-election of President Yeltsin, who then appointed him to the country’s national Security Council.

An important step in Berezovsky’s ambitious upward climb was his acquisition of Sibneft, Russia’s sixth-largest oil company. He gained this immensely important asset not through honest business practices or competitive bidding, but as a gift of the State Committee for the Management of State Property. Committee head Kokh simply appointed Berezovsky to take over Sibneft, and President Yeltsin signed the papers to approve the transfer. (Komsomolskaya Pravda [Moscow], Jan. 25).

Contributing to his image as the stereotypical international capitalist, Berezovsky ostentatiously roars around Moscow in a dark-blue bulletproof Mercedes 600, protected by a BMW in front, and bodyguards in Mitsubishi jeeps on either side. His private security staff numbers 150, including 20 former KGB technical surveillance specialists.

In the view of the country’s “democratic reformers,” the US News & World article continues, “Berezovsky and his ilk” have “exploited for personal gain wrongheaded economic reforms that were impoverishing the average man.” Berezovsky

has proved that building wealth in the new Russia has much to do with government cronies smoothing the way and little to do with free competition … Most disturbing of all to Russian reformers is the impunity with which Berezovsky has operated. His road to capitalism would have landed him in jail in most civilized countries, but brought no criminal charges in the new Russia.

Berezovsky, reports the New York Jewish weekly Forward (April 4, 1997), is “among those fabulously wealthy and hugely resented new Russian industrialists – robber barons accused of milking Russia dry – who bankrolled Mr. Yeltsin’s presidential campaign, buying the keys to the state.” Berezovsky has publicly boasted that he and six other top businessmen – some of them Jewish – control 50 percent of the Russian economy.

Not long ago Berezovsky bragged to the London Financial Times: “We hired [First Deputy Prime Minister] Chubais. We invested huge sums of money. We guaranteed Yeltsin’s election. Now we have the right to occupy government posts and use the fruits of our victory.” (Quoted in Forward, April 4, 1997)

An article in a December issue of the American business magazine Forbes accuses Berezovsky of running a criminally corrupt business organization. Headlined “Godfather of the Kremlin?,” the article concludes “It sure looks that way.”

A major scandal erupted in late 1996, following Yeltsin’s appointment of Berezovsky as deputy chief of Russia’s national Security Council (akin to the US National Security Council), when it was revealed that he had acquired Israeli citizenship three years earlier.

Responding to those who questioned the propriety of a wealthy businessman with foreign citizenship holding a highly sensitive security post, “Berezovsky and a number of television and newspapers journalists in his employ responded with racial demagoguery, accusing his critics of anti-Semitism.” Berezovsky “met with the editors of Izvestia for a series of interviews in which he mixed charges of anti-Semitism with thinly veiled threats of violence.” (Forward, Nov. 22, 1996) He has even brazenly insisted that Yeltsin has a moral and material obligation to Jewish business in Russia. (Komsomolskaya Pravda, Nov. 5, 1996).

“Every Jew, regardless of where he is born or lives, is de facto a citizen of Israel,” Berezovsky declared in a candid response to his critics. “The fact that I have annulled my Israeli citizenship today in no way changes the fact that I am a Jew and can again become a citizen of Israel whenever I choose. Let there be no illusions about it, ‘every Jew in Russia is a dual citizen’.” (Segodnya [“Today”], Nov. 14, 1996).

The Security Committee of Russia’s parliament (the Duma) has appealed to Yeltsin to remove Berezovsky from his sensitive Security Council position on the grounds that his dual Israeli-Russian citizenship legally disqualifies him from occupying the post. According to the Russian Federation’s Citizenship Law, he could legally occupy this post only on the basis of a specific agreement between Russia and Israel. No such agreement exists. Moreover, the Duma committee contends, Berezovsky is further disqualified because he has failed to sever his business connections after accepting the position. Finally, before he could be given legal access to classified information, the Federal Security Service would have to investigate and clear him. (Segodnya [Moscow], Feb. 19)

With good reason, the well-informed Jewish weekly Forward (Nov. 22) has expressed concern that Berezovsky’s illicit business activities and his arrogant public statements, as well as President Yeltsin’s indulgence of him, may aggravate anti-Jewish sentiment and thereby jeopardize the future of all of Russia’s Jews:

Given that many of the moguls who backed Mr. Yeltsin’s [reelection] campaign, including Mr. Berezovsky, are Jews, it seemed he was tempting, if not openly inviting, anti-Semitic conspiracy theories … Yeltsin’s failure to fire Berezovsky really puts the future of democracy in Russia, and the bizarre situation of the Jews there, in even sharper focus.

Vladimir Gusinsky

Nearly as rich and as influential as Berezovsky is Vladimir Gusinsky, another immensely wealthy Jewish banker and media magnate who played a key role in reelecting Yeltsin. (Forward, April 4, 1997) An outspoken advocate of Jewish interests, Gusinsky is a close ally of presidential chief of staff, Chubais. According to a Wall Street Journal report, he has ties to organized crime.

After a meteoric career building Most Bank, Gusinsky now devotes his energies to Media-Most, a new media holding company that includes the important NTV television network; a slick television weekly, “7 Days”; a popular radio station, “Echo of Moscow”; and a weekly news magazine, Itogi, which is published in partnership with Newsweek (owned by the Washington Post company); NTV-Plus satellite television network; and a 100,000-circulation daily newspaper, Sevodnya. (The Washington Post, March 31, 1997). He also has close connections with international media tycoon Rupert Murdoch.

When Prime Minister Chernomyrdin arrived in Washington, DC, in early February for a meeting with President Clinton, the 44-year-old Gusinsky accompanied him. On the day of their arrival, author/ journalist Georgie Anne Geyer wrote (Washington Times, Feb. 6):

On the surface Gusinsky is chairman of the powerful Most Bank and the “independent” Moscow TV … His bank was on the CIA’s recent list of banks with Russian mafia connections. In 1994, Most Bank was the scene of a bitter shootout with Mr. Yeltsin’s then-favorite KGB General Aleksander Korzhakov after which Mr. Gusinsky and his family temporarily exiled themselves to London. Most Bank is also known as a veritable den of former KGB men, and not KGB men from the professional intelligence sections, but from the notorious “Fifth Chief Directorate.”

Mr. Gusinsky now has a new role to play. He has had himself named head of the Russian Jewish Congress, and the suspicion is widespread that he will use his growing contacts with the American Jewish community to cry “Discrimination!” whenever anyone dares to criticize his business methods … We need to recognize what a delicate and dangerous moment this is in Russia when President Yeltsin’s life hangs in the balance, and men like Mr. Berezovsky and Mr. Gusinsky are readying to fill the vacuum that will surely open soon. They have talked publicly about using “constitutional means” when the time comes to insure an appointed president rather than new elections (in particular to avoid a victory of the honest General Aleksandr Lebed).

Crucial Jewish Role

No one can really understand Russia’s tumultuous social, political and economic situation, with its complex contending forces, without an awareness of the role of Jews, both in the past and today, and the popular attitude toward them.

During the Soviet era, Jews played a prominent, perhaps dominant, role in the ruling Communist Party and in economic, cultural and academic life. [See: M. Weber, “The Jewish Role in the Bolshevik Revolution and the Early Soviet Regime,” Jan.–Feb. 1994 Journal, pp. 4–14.] Today Jews hold conspicuous positions of great wealth and authority. Although they make up perhaps three percent of the total population, Jews wield power vastly disproportionate to their numbers. As the London Times noted recently (Jan. 27, 1997):

Prominent Jewish figures today enjoy unprecedented positions of power in politics, the media and the private sector, and have emerged as some of Russia’s most creative and talented minds. Boris Berezovsky, the most influential Russian Jew, who holds the post of deputy head of the Security Council as well as controlling a small business empire, even boasted recently that the country was run by seven key bankers, most of them Jewish.

Although anti-Semitism is still a powerful undercurrent in Russian society, and could resurface in the event of a nationalist leader coming to power, for the moment anti-Jewish sentiment is rarely voiced openly.

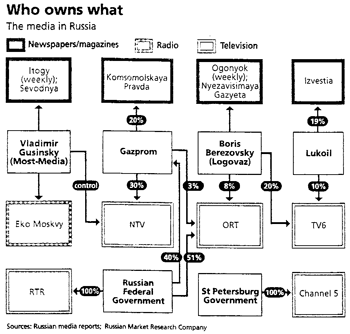

This chart from the London “Economist” (Feb. 25, 1997) shows the close ties linking business, media and government in Russia. The Russian federal government, for example, controls 100% of RTR television, 40% of the country's gas monopoly company, and 51% of ORT television, while the St. Petersburg city government controls 100% of Channel 5 television. Jewish businessman Boris Berezovsky controls Logovaz, the country's most prestigious automobile manufacturer, and has partial control of ORT and TV6 television, as well as the newspaper “Nezavisimaya Gazeta” and the weekly magazine “Ogonyok.” Another Jewish businessman, Vladimir Gusinsky, controls NTV television, “Sevodnya” newspaper, and the weekly news magazine “Itogi.”

Besides such business figures as Berezovsky and Gusinsky, a recent Forward article (April 4, 1997) cites such high-ranking Jewish government officials as: Boris Nemstov, first deputy prime minister in charge of social welfare, housing reform and restructuring of government monopolies; Yakov Urinson, deputy prime minister for economic affairs; and, Aleksandr Livshits, deputy head of Yeltsin’s administration.

Anti-Semitism was strictly illegal during the Soviet era. Today anti-Jewish sentiment is not only widespread, it is openly and sometimes forcefully expressed, in spite of Yeltsin government disapproval. Russian newspapers frequently and often emotionally discuss their country’s national-ethnic questions, the re-awakening Russian nationalism, and the role of Jews in society, in terms of an ongoing struggle between nationalism and internationalism. “Isn’t it a pity that anti-Semitism is flourishing in Russia today like ‘chrysanthemums in a garden’,” the frankly nationalist paper Zavtra (“Tomorrow”) sarcastically comments (No. 47, Nov 1996).

Even Gennady Zyuganov, leader of the reconstituted Communist Party (currently the main opposition political force), has written in his book, I Believe in Russia:

The ideology, culture and world outlook of the Western world became more and more influenced by the Jews scattered around the world. Jewish influence grew not by the day, but by the hour.

Reflecting the widespread bitterness of many Russians is a front-page article in Zavtra (Nov. 1996, No. 48), which charges that a group of “13 banker apostles” has gained control of the country. It went on to warn readers: “ … The Constitution has been one-third torn to pieces right under your nose in the last five years, and from this day on you will live under the jurisdiction of the Jewish bankers whose wallets protect the thugs of [television stations] ORT and NTV.”

Informed Russians are quite aware of America’s special relationship with Israel, with the Jewish lobby’s mighty influence in the United States, with the preferential treatment given by the US immigration agency (INS) to Jewish immigrants, and with the zealous US concern for Jewish welfare in general. Accordingly, Russian nationalists tend to view Jewish capitalists in their country as quasi-agents of the United States.

Concerned about a possible backlash, many Russian Jews, reports the Moscow correspondent of the Forward (April 4, 1997), now say that “there are too many Jews in government. There are too many Jewish bankers running the country.” Jews fear that with such a conspicuous profile they will be viewed as a group that has grown wealthy through dishonest practices at the expense of the productive working people, and that Russians will blame them for humiliating and ruining the nation. Anyway, a prominent Jewish community leader notes, “people here have quite bitter memories of the participation of Jews in the [Bolshevik] revolution.” (Forward, April 4, 1997)

Writing in Zavtra (No. 43, Oct. 1996), analyst Aleksandr Sevastyanov describes the contrasting attitudes of Russians and Jews with regard to Russia’s future:

There are many Jews in the country who preach the idea of a new Russian empire for the simple reason that for them Russian imperialism is a synonym for internationalism under new circumstances. Not having succeeded in its time with the Comintern [the Soviet- controlled Communist International], they now say “let’s try an empire.” Their ideal is a flourishing multinational Russia, where the Russians themselves are not really the rulers.

For us nationalists, this kind of Russia is pure nonsense – not worth our time or our support. Every normal Russian believes in his heart, and rightly so: “We have created this state and we shall rule it.” On the other hand, every typical Jew thinks to himself: “Yes, you Russians created the state, but we Jews shall rule it because we are the elite of the Russian nation, the natural claimants to the role of an imperial people. And we shall do so because we are the richest, the most united, the best educated, and the most cultured. If we do not rule Russia, then who?”

And, alas, today we Russians are not yet in a position even to pretend to an imperial role. The Soviet empire collapsed because the Russian people lost the ability to preserve or prevent the collapse of the great nation they had been built up over the centuries. To attempt to recapture its former ruling role, without first recapturing the ethnic strength that made it possible, would be suicidal. Solzhenitsyn is again right when he says: “Any attempt to restore the empire today would be tantamount to burying the Russian people.” We must first concentrate on solving the problems that have weakened us as a people. They are, first and foremost, demographic, and only secondarily economic, social, military, cultural, and the rest. We most reject all other activities that do not focus on the revitalization of our people. We cannot permit ourselves to be diverted from our absolutely essential goal, which is ethno-egocentric – not even by the ephemeral lure of empire building.

A Time of Ominous Transition

Still emerging from seven decades of Soviet rule, Russians are groping toward a new sense of national identity. Not yet having come to grips with its past, this is a land of historical paradox. Thus, Lenin’s embalmed corpse is still enshrined in a monumental sarcophagus on Moscow’s Red Square, and not a single former Communist official has been brought to trial for Soviet-era crimes.

As Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn has observed, Russia today is neither an authentic political democracy nor a genuine free market economy. While an ambitious few amass vast fortunes and great power through illicit deals, the country’s productive workers, children and elderly suffer. A small oligarchy rules over a population that lives in near destitution. “Democracy in the true sense of the word does not exist in Russia,” writes Solzhenitsyn. He continues:

There exists no legal framework or financial means for the creation of local self-government. People will have no choice but to achieve it through social struggle … This system of centralized power cannot be called a democracy … The fate of the country is now decided by a stable oligarchy of 150–200 people, which includes the nimbler members of the old Communist system’s top and middle ranks, plus the nouveaux riches … Our present ruling circles have not shown themselves in the least morally superior to the Communists who preceded them … Russia is being exhausted by crime, not a single serious crime has been exposed, nor has there been a single public trial … This destructive course of events over the last decade has come about because the government, while ineptly imitating foreign models, has completely disregarded the country’s innate creativity and singular character as well as Russia’s centuries-old spiritual and social traditions.

For the historically minded observer, the parallels between Russia today and Germany during the pre-Hitler Weimar republic years are striking and portentous. In each case, there has been severe economic, political and social upheaval, monetary chaos, substantial loss of territory, and humiliating subordination to foreign powers following the abrupt collapse of an seemingly entrenched political regime. Unscrupulous individuals, many of them members of an alien ethnic minority, have exploited their foreign connections and the prevailing disorder to quickly enrich themselves at the expense of the common people. Major media and financial institutions are largely in the hands of people with no national loyalty. In each case, the social dislocation has come with a drastic fall in cultural and moral standards.

Much of the talk in the United States about democracy in Russia is as ridiculous today as it has always been. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. Throughout its history, Russia has been ruled by an elite, entrenched in Moscow and St. Petersburg, often of non-Russian origin and fascinated by Western philosophies.

As a potentially wealthy country with a proud and illustrious past, it is difficult to imagine that Russians will permit the current miserable and humiliating situation to continue indefinitely. At the same time, it’s hard to see how Russia’s problems can be mastered without very drastic change.

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 16, no. 3 (May/June 1997), pp. 21-27

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a