Examining Stalin’s 1941 Plan to Attack Germany

Book Review

Unternehmen Barbarossa und der russische Historikerstreit (“Operation Barbarossa and the Russian Historians’ Dispute”), by Wolfgang Strauss. Munich: Herbig, 1998. Hardcover. 199 pages. Illustrations. Source references. Bibliography. Index.

No two peoples suffered more during the Second World War than the Russians and the Germans. In the carnage of that great global conflict, nothing matched the massive destruction of life and property wrought on the Eastern front by Russian and German forces fanatically driven by irreconcilable ideologies.

Now, more than 50 years after the end of the “clash of the titans,” free Russian and German historians are collaborating to ascertain the historical decisions and actions that led to that bloodiest of all conflicts. Wolfgang Strauss, a respected German Slavicist and political analyst, explains this clarifying historical process in “Operation Barbarossa and the Russian Historians’ Dispute,” his most recent work.[1] He examines here the research of revisionist scholars in Russia and Germany on Stalin’s role in igniting the German-Russian conflict and his efforts to expand the Soviet empire across Europe. Perhaps most importantly, he also shows how a shared understanding of the war is contributing to reconciliation between these two great European peoples.

Strauss affirms the view of German historian Ernst Nolte that Hitler’s militant anti-Communism was an understandable reaction to the looming Soviet threat to Europe and humanity. Put another way, the militancy of the “fascist” movements that arose in Germany, Spain, Italy and other European countries in the 1920s and 1930s was, in essence, a response to the undisguised Bolshevik goal of dominating Europe.[2] This view, Strauss contends, has now largely been embraced by Russian revisionists and the French historian François Furet.[3] It is basically irrelevant whether one regards the war that broke out in June 1941 between Germany and Soviet Russia as a war of aggression, a preventive war or a counterattack. For each side, Nolte and others contend, this was a life or death struggle to decide which world view and way of life would prevail in Europe – atheistic, internationalist Communism or the bourgeois Christian civilization of the West.

The Black Book

In no way does Strauss dismiss or whitewash Hitler’s brutal excesses. He also holds that Hitler’s racist concept of the inferiority of the Slavic peoples and his attempt to colonize their lands was not only wrong but doomed his military campaign, and ultimately the Third Reich, to failure. At the same time, Strauss stresses the monumental brutality of Soviet and international Communism. In this regard he cites The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror and Repression, a recent 860-page work by French scholar Stéphane Courtois and others.[4]

As Courtois stresses, many American and European scholars have upheld a morally peculiar view of history that fervently condemns National Socialist Germany while maintaining a meretriciously non-judgmental “objectivity” toward Soviet Russia. But there is no hierarchy of death and suffering. As Courtois writes: “The death of a Ukrainian peasant child, deliberately exposed to starvation by the Stalinist regime, is just as important as the starvation of a child in the Warsaw Ghetto.”

As Strauss relates, Courtois finds that 1) some 100 million human beings lost their lives as a result of Communist policies in the Soviet Union, Red China and other Communist states 2) The Communists made mass criminality an integral part of their governmental system; 3) Terror was part of the Soviet regime from the outset, beginning with Lenin; 4) Class and ethnic genocide, begun by Lenin and systematized by Stalin, preceded Hitler’s dictatorship by years; 5) Stalin was unquestionably a greater criminal than Hitler; and 6) Stalin’s joint, if not primary, responsibility for the outbreak of Russo-German War is undeniable.[5]

It is often forgotten that the Russian people were the first victims of Communism. Citing evidence from British, Russian and other sources, Strauss shows that those who imposed Communist despotism on the Russians were primarily non-Russian and non-Christian aliens – above all, Jews.[6] Their goal was nothing short of eradicating Christianity and European civilization, at whatever the human cost. Many Russians place the primary responsibility for the crimes of Communism, particularly in the first ten years of Soviet rule, on the Bolshevik party’s non-Russian elements. For example, Strauss notes, the Russian press has referred to the execution of Tsar Nicholas II and his entire family as a “Jewish ritualistic murder.”[7] In a similar context, Strauss cites from Solzhenitsyn the names of the ruthless Soviet secret police (NKVD) chiefs – all of them Jews – who put tens of thousands of slave laborers to death under appallingly inhumane conditions in building the White Sea Canal.[8]

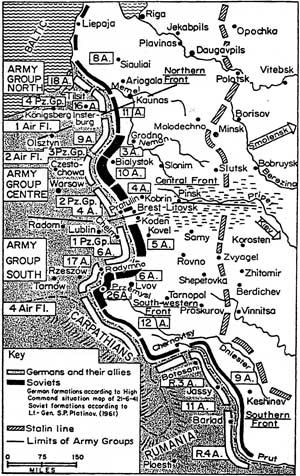

Just prior to the “Barbarossa” attack on the morning of June 22, 1941, two colossal military forces were poised on each side of the Soviet frontier. Three million German men, with 600,000 vehicles, 750,000 horses, 3,580 tanks, and 1,830 aircraft, were deployed in three large “Army Groups,” together with some 600,000 Romanian and Finnish troops. On the Soviet side, 4.5 million Red Army troops were deployed against Germany and Europe. Source: Paul Carell, “Hitler Moves East 1941-1943” (1991), p. 18.

One should not, however, get the impression that Slavs were the exclusive victims of Stalin’s terror, or that the murderers were all non-Russians.[9] During the Great Purge of 1937-39, Strauss points out, Stalin executed many Jews who had played a prominent role in the early Soviet regime. In 1940 Stalin succeeded in killing his greatest rival, Lev Trotsky (Bronstein), who had once been the second most powerful figure in the Soviet state. And when Stalin installed the Russian Nikolai Yezhov as head of the NKVD, replacing the Jewish Genrikh Yagoda, thousands of Yagoda’s followers and their families, mostly Jews, were murdered or committed suicide.

Pioneering Russian Revisionists

One of the earliest Russian revisionists of World War II history was Pyotr Grigorenko, a Soviet Army Major General and highly decorated war veteran who taught at the Frunze Military Academy. Already in the early 1960s, during the Khrushchev era, he was a “dissident,” publicly supporting civil rights for oppressed ethnic minorities. (Authorities committed him to a mental asylum.) In 1967, Strauss relates, he was the first leading Soviet figure to advance the revisionist arguments, which became well known during the 1980s and 1990s, on Stalin’s preparations for aggressive war against Germany. In an article submitted to a major Soviet journal (but rejected, and later published abroad), Grigorenko pointed out that Soviet military forces vastly outnumbered German forces in 1941. Just prior to the German attack on June 22, 1941, more than half of the Soviet forces were in the area near and west of Bialystok, that is, in an area deep in Polish occupied territory. “This deployment could only be justified” wrote Grigorenko, “if these troops were deploying for a surprise offensive. In the event of an enemy attack these troops would soon be encircled.”[10]

The best known Russian historian to advance revisionist arguments on Stalin’s preparations for a first-strike against Germany has been Viktor Suvorov (pen name of Vladimir Rezun). Strauss recapitulates his main arguments (which have been treated in detail in the pages of this Journal).[11]

Strauss examines three significant speeches by Stalin (which have also been dealt with by Suvorov, as well as in the pages of this Journal):[12] 1. In his address of August 19, 1939, shortly before the outbreak of war, Stalin explained why a temporary alliance with Germany was more beneficial to Soviet interests than an alliance with Britain and France. 2. In his speech of May 5, 1941, Stalin explained to graduate officers of military academies that the impending war would be fought offensively by Soviet forces, and that it would nonetheless be a just war because it would advance world socialism. 3. In the speech of November 6, 1941, some four months after the outbreak of the “Barbarossa” campaign, Stalin stressed the importance of killing Germans. (This speech helped to “inspire” the Soviet Jewish writer Ilya Ehrenburg to make his notorious contribution to the war effort in the form of murderously anti-German propaganda.)

Recent Russian Revisionist Historiography

A radical revision of World War II history, Strauss contends, became possible only after the collapse of the multinational Soviet Union (1991), when some 14 million previously classified documents dealing with all aspects of Soviet rule were finally open to free examination. This book’s greatest contribution may well be to highlight for non-Russians the research of Russian revisionists. Strauss is very familiar with this important work, which has been all but entirely ignored in the United States. The most important publications cited by Strauss in this regard are two Russian anthologies, both issued in 1995: “Did Stalin Make Preparations for an Offensive War Against Hitler?,” and “September 1, 1939-May 9, 1945: 50th Anniversary of the Defeat of Fascist Germany.”[13] The first of these contains articles by revisionist scholars as well as by critics of revisionism. (The “Russian historians’ dispute” referred to in the subtitle of Strauss’ book echoes the “German historians’ dispute” of the 1980s, in which Ernst Nolte played a major role.)

As Strauss notes, the most prominent critic of the revisionist view of Suvorov and others has been Israeli historian Gabriel Gorodetsky, who teaches at Tel Aviv University. (Strauss suggests that he is an long-time apologist for Stalin.) Gorodetsky is the author of a 1995 Russian-language anti-Suvorov work, “The ‘Icebreaker’ Myth,” and a detailed 1999 study, Grand Illusion: Stalin and the German Invasion of Russia.

In his discussion of “Did Stalin Make Preparations for an Offensive War Against Hitler,” Strauss writes (pages 42-44):

Even though revisionists as well as the critics of revisionism have their say in this book, the end result is the same. The anti-Fascist attempts to justify and legitimize Stalin’s war policy from 1939 do not hold up. The view that the Second World War was “a crime attributable solely to National Socialist Germany” can no longer be sustained. The historical truth as seen by Russian revisionists is documented in this collection of articles published by Bordyugov and Nevezhin as well as by the renowned war historian Mikhail Melitiukhov, academic associate of the All-Russian Research Institute for Documentation and Archives.

This most recent compendium of Russian revisionist writings deepens our understanding of Stalin’s preparations for a military first-strike against Germany in the summer of 1941. The strategic deployment plan, approved by Stalin at a conference on May 15, 1941, with General Staff chief Georgi Zhukov and Defense Commissar Semen Timoshenko, called for a Blitzkrieg:

Tank divisions and mechanized corps were to launch their attack from the Brest and Lviv [Lemberg] tier accompanied by destructive air strikes. The objective was to conquer East Prussia, Poland, Silesia and the [Czech] Protectorate, and thereby cut Germany off from the Balkans and the Romanian oil fields. Lublin, Warsaw, Kattowice, Cracow, Breslau [Wroclaw] and Prague were targets to be attacked.

A second attack thrust was to be directed at Romania, with the capture of Bucharest. The successful accomplishment of the immediate aims, namely, to destroy the mass of the German Army east of the Vistula, Narev and Oder rivers, was the necessary prerequisite for the fulfillment of the main objective, which was to defeat Germany in a quick campaign. The main contingents of the German armed forces were to be encircled and destroyed by tank armies in bold rapid advances.

Three recurrent terms in the mobilization plan of May 15 confirm the aggressive character of Stalin’s plan. “A sudden strike” (vnyyzapni udar), “forward deployment” (razvertyvaniye), and “offensive war” (nastupatel’naya voyna). Of the 303 [Soviet] divisions assembled on the western front, 172 were assigned to the first wave of attack. One month was allotted for the total deployment – the period from June 15 to July 15. Mikhail Melitiukhov: “On this basis it appears that the war against Germany would have to have begun in July.”

This anthology also devotes much attention to analyzing Stalin’s speech of May 5, 1941, delivered to graduates of Soviet military academies. In this speech Stalin justified his change of foreign policy in connection with the now decided-upon attack against Germany. From the Communist point of view even a Soviet war of aggression is a “just war” because it serves to expand the “territory of the socialist world” and “to destroy the capitalist world.” Most important in this May 5 speech was Stalin’s efforts to dispel the “myth of the invincible Wehrmacht.” The Red Army was strong enough to smash any enemy, even the “seemingly invincible Wehrmacht.”

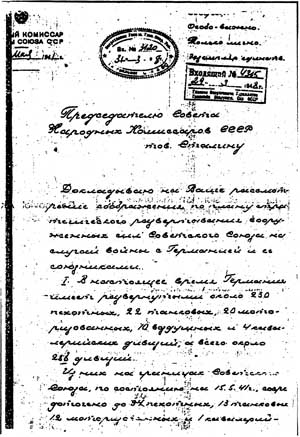

First page of the May 1941 Soviet memorandum, shown here in facsimile (reduced), that lays out strategy for a military first strike against Germany and her allies. Using such terms as “a sudden strike” and “offensive war,” it calls for a lightning attack against German East Prussia, Poland, Silesia and the Czech lands, thereby cutting Germany off from the Balkans and the Romanian oil fields, and a second military thrust directed at Romania. This document, says Russian historian Melitiukhov, suggests that the Soviet strike against Germany and her allies was set to begin in July 1941. Hand-written in black ink, this 15-page document was prepared by Soviet general Vasilevski, and signed by Soviet General Staff chief Zhukov and Soviet defense commissar Timoshenko. It was submitted to Stalin on May 15, 1941. The rectangle and oval archive stamps show that this document was transferred in 1948 to the operations bureau of the Soviet General Staff.

Strauss lists (pages 102-105) the major findings and conclusions of Russian revisionists, derived mostly from the two major works cited above:

- Stalin wanted a general European war of exhaustion in which the USSR would intervene at the politically and militarily most expedient moment. Stalin’s main intention is seen in his speech to the Politburo of August 19, 1939.

- To ignite this, Stalin used the [August 1939] Soviet-German Non-Aggression Pact, which: a) provoked Hitler’s attack against Poland, and b) evoked the declarations of war [against Germany] by Britain and France.

- In the event Germany was defeated quickly [by Britain and France], Stalin planned to “Sovietize” Germany and establish a “Communist government” there, but with the danger that the victorious capitalist powers would never permit a Communist Germany.

- In the event France was defeated quickly [by Germany], Stalin planned the “Sovietization” of France. “A Communist revolution would seem inevitable, and we could take advantage of this for our own purposes by rushing to aid France and making her our ally. As a result of this, all the nations under the ‘protection’ of a victorious Germany would become our allies.”

- From the outset Stalin reckoned on a war with Germany, and the [Soviet] conquest of Germany. To this end, Stalin concentrated on the western border of the USSR operational offensive forces, which were five- to six-times stronger than the Wehrmacht with respect to tanks, aircraft and artillery.

- With respect to a war of aggression, on May 15, 1941, the Red Army’s Main Political Directorate instructed troop commanders that every war the USSR engaged in, whether defensive or offensive, would have the character of a “just war.”

- Troop contingents were to be brought up to full strength in all the western military districts; airfields and supply bases to support a forward-strategy were to be built directly behind the border; an attack force of 60 divisions was to be set up in the Ukraine and mountain divisions and a parachute corps were to be established for attack operations.

- The 16th, 19th, 21st, 22nd and 25th Soviet Armies were transferred from the interior to the western border, and deployed at take-off points for the planned offensive.

- In his speech of May 5, 1941, to graduate officers of the academies, Stalin said that war with Germany was inevitable, and characterized it as a war not only of a defensive nature but rather of an offensive nature.

- Stalin intended to attack in July 1941, although Russian historians disagree about the precise date. Suvorov cites July 6, [Valeri] Danilov [a retired Soviet Colonel] gives July 2, while Melitiukhov writes: “The Red Army could not have carried out an attack before July 15.”

General Alfred Jodl, center, makes a point about the military situation during a briefing with Hitler and General Wilhelm Keitel.

Hitler’s Proclamation

In an appendix of documents, Strauss includes portions of Hitler’s “Operation Barbarossa” directive of December 18, 1940. Also here, in facsimile, is a German press announcement of June 22, 1941, that gives Hitler’s reasons for Germany’s attack against the Soviet Union:

This morning the Führer, through Reich Minister Dr. Goebbels, issued a proclamation to the German people in which he explains that after months-long silence he can finally speak openly to the German people about the dangerous machinations of the Jewish-Bolshevik rulers in Soviet Russia. After the German-Russian Friendship Treaty in the Autumn of 1939, he hoped for an easing of tensions with Russia. This hope, however, was crushed by Soviet Russia’s extortionist demands against both Finland and the Baltic states as well as against Romania.

After the victory in Poland the Western powers rejected the Führer’s proposal for an understanding because they were hoping that Soviet Russia would attack Germany. Since the Spring of 1940 Soviet troops have been deploying in ever increasing numbers along the German border, so that since August 1940 strong German forces have been tied down in the East, making any major German effort in the West impossible.

During his [November 1940] visit to Berlin, [Soviet foreign minister] Molotov posed questions regarding Romania, Finland, Bulgaria and the Dardanelles that clearly revealed that Soviet Russia intended to create trouble in eastern Europe. To be sure, the Bolshevik coup attempt against the [Romanian] government of Antonescu failed, but, with the help of the Anglo-Saxon powers [Britain and the United States], their putsch in Yugoslavia succeeded. Serbian air force officers flew to Russia and were immediately incorporated in the Army there.

With these machinations Moscow has not just broken the so-called German-Russian Friendship Treaty, it has betrayed it. In his proclamation the Führer stressed that further silence on his part would be a crime not only against Germany, but against Europe as well. On the border now stand 160 Russian divisions,[14] which have repeatedly violated that frontier. On June 17-18 Soviet patrols were forced back across the border only after a lengthy exchange of fire. Meanwhile, to protect Europe and defend against further Russian provocations, the greatest build-up of forces ever has been assembled against Soviet Russia. German troops stand from the Arctic Ocean to the Black Sea, allied in the north with Finnish troops and along the Bessarabian border with Romanian forces.

The Führer concluded his proclamation with the following sentences: “I have therefore decided to once again lay the fate and the future of the German Reich and of our people in the hands of our soldiers. May the Lord God help us especially in this struggle!”

Coming to Terms With the Past

Even though more and more independent Russian, German and other European historians support the revisionist arguments of Suvorov (and others), it still seems impossible, especially in Germany, to reapportion historical responsibility from Hitler to Stalin. In this regard, Strauss recalls (pages 45-46) a discussion in May 1993 at the Military History Research Office in Freiburg involving German historian Dr. Joachim Hoffmann, decades-long associate of the Research Office, and Russian historian Viktor Suvorov. Hoffman told of conversations on the “preventive war” issue he has had with prominent Germans, including President Richard von Weizsäcker, the influential journalist Marion Gräfin Dönhoff, and political figures Egon Bahr and Heinrich Graf von Einsiedel. In every case he was told that even if Suvorov is correct, and Hitler’s attack indeed preceded Stalin’s by weeks, this must not be acknowledged publicly because it would exonerate Hitler. This is typical, says Hoffmann, of the immoral attitude that prevails in Germany. In their egotism, he adds, these Germans do not realize that they are, in effect, demanding that Russians accept the propaganda lies of the Stalin era.

Dr. Joachim Hoffmann served from 1960 until 1995 as a historian with the semi-official Military History Research Office in Freiburg. His detailed revisionist work Stalin's Vernichtungskrieg, 1941-1945 (“Stalin's War of Annihilation”) has appeared in five editions. An English-language edition is being prepared for publication [by Theses & Dissertations Press; ed].

Strauss contrasts the very different attitudes of Germans and Russians toward 20th century history, and the role of historical revisionism. Whereas Germans are imbued with a national masochistic guilt complex about their collectively “evil” past, which was instilled during the postwar occupation as part of Allied “reeducation” campaign, and reinforced ever since in their media and by “their” political leaders, Russians are much more free and open about their Communist past, largely because they have not been occupied by foreign conquerers, and their media and educational system has not come under the control of outsiders.[15] Although die-hard Communists try to uphold the historiography of the Soviet era, most Russians want to know the truth about their past. After all, Strauss points out, one out of every two Russian families suffered under the Stalinist tyranny. For the time being, anyway, nothing is taboo in Russia, including the role of Jews in the Communist movement. (By contrast, Germans are forbidden by law to say anything derogatory about the political activities of Jews in the first half of the 20th century.)

The term “genocide” is used to refer particularly to the World War II treatment of Europe’s Jews. Without in any way minimizing the sufferings of innocent Jews caught up in that maelstrom, one should not forget that Stalin’s Soviet regime inflicted a much more ruthless and widespread genocide against the Russian and Ukrainian peoples. It is estimated that in the Soviet Union about 20 million people, the vast majority of them Slavs, lost their lives as a result of Soviet policies, either executed or otherwise perished in the Gulag prison network or as victims of imposed famine, and so forth. Millions of Germans were also victims of genocide. It is estimated that some four million Germans were killed or otherwise perished during the 1944-1948 period, victims of Allied-imposed “ethnic cleansing,” starvation, slave labor in the USSR, and in inhumane POW camps administered by the victorious Allies.[16]

In promoting greater understanding of the calamitous German-Russian clash of 1941-1945, German and Russian revisionist scholars foster reconciliation between these two peoples. Strauss cites recent developments that attest to this process. In Volgograd, victors and vanquished have joined to erect a monument dedicated to all the victims of the Battle of Stalingrad. Its inscription, written in Russian and German, reads: “This monument commemorates the suffering of the soldiers and civilians who fell here. We ask that those who died here and in captivity will rest in eternal peace in Russian soil.” On the outskirts of St. Petersburg a German soldiers’ cemetery and memorial was recently dedicated. Across Russia today, it is not unusual for Russian women to tend the graves of German soldiers. (Because the Soviet government did very little to help identify and provide decent burials for their war dead, few Russian women have had any idea where their own sons, brothers, and husbands fell.)

In the book’s epilogue, Strauss describes the fervent indignation and rage of Russians over the criminal capitalism that has taken hold in their country. The inequities between the nouveau riches and the mass of Russian working class people are now greater than under Soviet rule. Many Russian revisionists see an intrinsic resemblance and affinity between capitalism and Communism. Given that many former Soviet officials still hold office or otherwise wield power in the “new Russia,” everyone readily sees how easy it has been for members of the old Soviet elite – the Nomenklatura – to reemerge in Russia’s predatory capitalism as racketeers, gangsters, money speculators, bank frauders, extortionists and mafiosi. On the ruins of the Soviet system, writes Strauss, has emerged a new dictatorship of pitilessness, corruption, criminality, social division, poverty and despair. Resentment against the “reformist” policies advocated by the United States is widespread.

In this regard Strauss cites the views of Spanish writer Juan Goytisolo, who asserts that if this social pathology endures in Russia, then Karl Marx’s analysis will be proven correct, at least in part. While Marx was wrong about the promised virtues of Communism, writes Goytisolo, events seem to confirm his critique of capitalism, especially of unrestrained monetarism that knows only one value, namely, maximum profits regardless of human cost.[17]

Holding flowers, an 86-year-old German from the Aibling region of Bavaria searches memorial tablets for the names of comrades who gave their lives more than half a century ago in World War II. The stone memorial tablets stands at the recently dedicated soldiers' cemetery of Zolgubovka, near St. Petersburg.

‘Strong and Free’

Whether they call themselves “Reformers” (Westernizers), Communists or nationalists (“Eurasians”), Russians today, writes Strauss, overwhelmingly reject all forms of internationalism, whether Communist or capitalist. They want a Russia that is strong and free.

Toward this goal, many look to geopolitics, an outlook built on the Eurasian “heartland” theory expounded by 20th-century British geographer Halford Mackinder and promoted in Third Reich Germany by Karl Haushofer. (According to this theory, Russia has the potential for great power and prosperity because it is the core of the vast, resource-rich Eurasian heartland.) The leading exponent in Russia today of this view is Alexander Dugin, whose book, “The Basics of Geopolitics: Russia’s Geopolitical Future,” has been influential with both old Communists and new nationalists in a grouping sometimes referred to as the “national Bolshevik alliance,” and whose adherents are known as “Eurasianists.” Dugin is a close associate of Gennady Zyuganov, head of the country’s largest political party, the Russian Communist Party (which, in spite of its name, is much more nationalist than Marxist). Zyuganov himself is the author of a recent book, “The Geography of Victory: The Bases of Russian Geopolitics.”

Russia’s parliament, the Duma, has established a Committee of Geopolitical Affairs, chaired by Alexey Mitrofanov, a member of Vladimir Zhirinovksy’s Liberal Democratic Party. (Zhirinovsky proposes the formation of a Berlin-Moscow-Tokyo axis, and has been quoted as saying: “Today, the United States of America is the major enemy of our country. All our actions and dealings with America from now on should be undertaken with this in mind.”)

Notes

| [1] | Strauss, born in 1931, was arrested for anti-Communist activities as an Oberschüler (secondary school student) in East Germany (DDR) and imprisoned, 1950-1956. He is the author of several other notable books on Russia, including Russland wird leben: vom roten Stern zur Zarenfahne (1992), Drei Tage, die die Welt erschütterten (1992), Bürgerrechtler in der UdSSR (1979), and Von der Wiedergeburt slawophiler Ideen in Rußland (1977). He is also a frequent contributor to scholarly journals. He currently lives in Bavaria, where he works as a Slavic affairs specialist. |

| [2] | See: Ernst Nolte, Der Europäische Bürgerkrieg 1917-1945: Nationalsozialismus und Bolschewismus (Munich: 1997 [5th ed.]). Nolte has strongly suggested that Hitler’s wartime treatment of the Jews might legitimately be regarded as a defensive response by Hitler to the threat of Bolshevik mass murder of the Germans. In a 1980 lecture he said: “It is hard to deny that Hitler had good reason to be convinced of his enemies’ determination to annihilate long before the first information about the events in Auschwitz became public.” See also the interview with Nolte in the Jan.-Feb. 1994 Journal (Vol. 14, No. 1), pp. 15-22, and “Changing Perspectives on History in Germany: A Prestigious Award for Nolte: Portent of Greater Historical Objectivity?,” July-August 2000 Journal, pp. 29-32. |

| [3] | François Furet and Ernst Nolte, Feindliche Nähe: Kommunismus und Faschismus im 20. Jahrhundert: Ein Briefwechsel (Munich: 1998). |

| [4] | The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression, by Stéphane Courtois and others (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999). Original edition: Le livre noir du communisme: Crimes, terreur, répression (Paris: 1997). Earlier works by Courtois include Histoire du parti communiste français (1995), L’état du monde en 1945 (1994), Rigueur et passion (1994), 50 ans d’une passion française (1991), and Qui savait quoi? (1987). |

| [5] | Courtois has also written: “I am fighting for a reevaluation of Stalin. He was to be sure the greatest criminal of the century. But at the same time he was the greatest politician – the most competent, the most professional. He was the one who understood most perfectly how to put his resources at the service of his goals.” |

| [6] | Russian nationalists are fully aware, just as were the anti-Bolshevik “White Russians,” that the leaders of Russia’s Marxist movement – Mensheviks and Bolsheviks alike – were predominantly not Russian at all. As evidence of the alien character of the Bolshevik revolution and of the early Soviet regime, Russian nationalists (along with many others) often cite The Last Days of the Romanovs, a work by British writer Robert Wilton (and now translated into Russian). In an appendix to the 1993 IHR edition of this work (pp. 184-190), Wilton also notes: “According to data furnished by the Soviet press, out of important functionaries of the Bolshevik state… in 1918-1919 there were: 17 Russians, two Ukrainians, eleven Armenians, 35 Letts [Latvians], 15 Germans, one Hungarian, ten Georgians, three Poles, three Finns, one Czech, one Karaim, and 457 Jews.” See also: M. Weber, “The Jewish Role in the Bolshevik Revolution and the Early Soviet Regime,” Jan.-Feb. 1994 Journal, pp. 4-14. |

| [7] | A special 1996 edition of the Moscow newspaper Russkiy Vestnik lists the names of the executioners: Yankel Yurovsky, Anselm Fischer, Istvan Kolman, A. Chorwat, Isidor Edelstein, Imre Magy [?], Victor Grinfeld, Andreas Wergasi and S. Farkash. The article concludes: “All of this attests to the non-Russian origin of the murderers.” |

| [8] | According to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the six directors were Semyon Firin, Matvei Berman, Naftali Frenkel, Lazar Kogan, Yakov Rappoport, Sergei Zhuk. The Head of the Military Guards was Brodsky, the Canal Curator of the Central Executive Committee was Solts, the GPU and NKVD heads were Yagoda, Pauker, Spiegelglas, Kaznelson, Sakovskiy, Sorensen, Messing and Arshakuni. As the names indicate, all were non-Russians. Stalin awarded most of these murderers the honorary title “Hero of Labor.” See: Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, III-IV, Book Two (New York: Harper & Row, 1975), pp. 79, 81, 82, 84, 94, etc. |

| [9] | This generalization is mostly valid for the first 20 years of Soviet rule. However, following the Great Purge (1937-1939), and except for several years after World War II in East Europe where Stalin used Jewish Communists to instal puppet regimes, the dictator until his death actively opposed elements he referred to as cosmopolitans, parasites, and so forth. |

| [10] | Grigorenko originally submitted his article to the Soviet journal Voprosy istorii KPSS, which (of course) rejected it. It was published in 1969 by Possev, a Russian emigré publishing house in Frankfurt am Main. |

| [11] | Suvorov’s first three books on World War II have been reviewed in The Journal of Historical Review. The first two, Icebreaker and “M Day,” were reviewed in Nov.-Dec. 1997 Journal (Vol. 16, No. 6), pp. 22-34. His third book, “The Last Republic,” was reviewed in the July-August 1998 Journal (Vol. 17, No. 4), pp. 30-37. |

| [12] | See the review of Stalins Falle (“Stalin’s Trap”), by Adolf von Thadden, in the May-June 1999 Journal, pp. 40-45. |

| [13] | Gotovil li Stalin nastupatel’nuyu voynu protiv Gitlera (“Did Stalin Make Preparations for an Offensive War Against Hitler?,” by Grigoriy Bordyugov and Vladimir Nevezhin (Moscow: AIRO XX, 1995), and, 1 sentyabrya 1939-9 maya 1945: Pyatidesyatiletiye razgroma fashistkoy Germanii v Kontekste Nachala Vtoroy Mirovoy Voyny (“September 1, 1939-May 9, 1945: the 50th Anniversary of the Defeat of Fascist Germany in the Context of the Beginning of the War”), edited by I.V. Pavlova and V. L. Doroshenko (Novosibirsk Memorial, 1995). The latter work was briefly cited in the Nov.-Dec. 1997 Journal, pp. 32-34. |

| [14] | The German High Command greatly underestimated the number of Soviet divisions, as well as the quality and quantity of Soviet tanks. Hitler and the Wehrmacht were to find not 160 divisions on their doorstep, but more than 300. See: David Irving, Hitler’s War (New York: Viking, 1977), pp. 205-206, 297. On the correlation of forces in June 1941, see also Joachim Hoffmann, Stalins Vernichtungskrieg 1941-1945 (Munich, 1995), Chapter 1, and esp. pp. 31, 66. |

| [15] | Ominously, however, the “oligarchs,” most of them Jewish, exercise considerable control over the Russian media. See: Daniel W. Michaels, “Capitalism in the New Russia,” May-June 1997 Journal, pp. 21-27, and, “A Jewish Appeal to Russia’s Elite,” Nov.-Dec. 1998 Journal, pp. 13-18. |

| [16] | See: Alfred-Maurice de Zayas, The German Expellees: Victims in War and Peace (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1993), Alfred-M. de Zayas, Nemesis at Potsdam: The Expulsion of the Germans From the East (Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska, 1989 [3rd rev. ed.]), James Bacque, Other Losses (Prima, 1991), J. Bacque, Crimes and Mercies (Little, Brown, 1997), Ralph Keeling, Gruesome Harvest: The Allies’ Postwar War Against the German People (IHR, 1992). |

| [17] | Juan Goytisolo, La Saga de los Marx (Barcelona: Mondadori, 1993). Although Goytisolo was undoubtedly one of Spain’s foremost 20th century novelists, both his political views and private life were highly controversial. Expelled from Spain by Franco, he lived most of his life in France. |

“The price of freedom is eternal vigilance.”

—Thomas Jefferson

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 19, no. 6 (November/December 2000), pp. 40-47

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a