'Fuss and Flapdoodle” About Pearl Harbor

Book Review

Pearl Harbor: Final Judgement, by Henry C. Clausen and Bruce Lee. New York: Crown, 1992. Hardcover. 485 (+ x) pages. Photos. Notes. Appendices. Index. ISBN: 0 517 58644 4.

James J. Martin graduated from the University of New Hampshire in 1942 and received his M.A. (1945) and Ph.D. (1949) degrees in History from the University of Michigan. His teaching career has spanned 25 years and involved residence at educational institutions from coast to coast. Dr. Martin's books have included the two-volume classic, American Liberalism and World Politics, 19311941, as well as Beyond Pearl Harbor, The Man Who Invented 'Genocide': The Public Career and Consequences of Raphael Lemkin, and An American Adventure in Bookburning in the Style of 1918. He is also author of two collections of essays: Revisionist Viewpoints and The Saga of Hog Island and Other Essays in Inconvenient History. Dr. Martin has contributed to several editions of theEncyclopaedia Britannica, and is a three-time contributor to the Dictionary of American Biography.

The fourth of the ten (some students combine two and come up with nine) investigations of the Pearl Harbor attack of December 7, 1941, was the result of an authorization by the United States Congress. A Senate Joint Resolution of June 13, 1944, directed the Departments of the Army and Navy to conduct their own investigations, which was promptly followed by the Secretaries of these Departments appointing personnel to conduct such investigations and the beginning of hearings, which were to take awhile.

The Army Pearl Harbor Board (APHB) consisted of three Generals plus a supporting staff of three, an Executive Officer,a Recorder, and an Assistant Recorder, the latter three having no vote in the Board's final disposition. The Assistant Recorder was a 39-year-old San Francisco lawyer, Henry C. Clausen, who had come into the army two years earlier, ostensibly by taking a commission, not as a draftee foot-soldier. How the lightning had managed to strike Clausen for appointment to such a crucial job no one ever explained, but anyone who has gone over the repeated citations in later years of Clausen's heated admiration of War Secretary Henry L. Stimson, which had not abated even 50 years after his entry into the armed services, can probably figure it out for themselves.

The findings of the APHB, which have been exhaustively examined for more than four and a half decades, take months to read. Charles A. Beard alone devoted parts of three chapters of his 1948 book, President Roosevelt and the Coming of the War 1941, to such an examination, and there are numerous somewhat shorter analyses and commentaries on it all. For our purposes it is sufficient to observe that the Board came to conclusions which angered the Secretary of War and led to a determination to undermine its findings, even if it required that pressure be placed on some of its witnesses to recant sworn testimony making them, in substance, perjurers.

What the Board did was to reverse the flow of criticism for what had happened, away from the Army and Navy commanders at Pearl – which had been the original desire of the authorities in Washington – and once more to direct it at the superiors of those in Hawaii who took orders. This therefore required the top people in Washington to put into effect a comprehensive program of Pearl Harbor responsibility damage-control; it is here that we find Atty. Clausen as chief of the cast of characters in the book at hand.

When the APHB singled out Secretary Stimson's direct subordinate, Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, as responsible for the Army not being ready to defend the fleet based at Pearl Harbor on the morning of December 7, 1941, they angered the Secretary. That and other charges convinced Stimson that something had to be done to soften the Board's verdict and once more lay the blame elsewhere. For the first two and a half years the sentiment had been well established by the first big political investigation, conducted under the direction of Supreme Court Justice Owen J. Roberts (Dec. 18, 1941 to Jan. 23, 1942). It found that all in Washington were innocent of any dereliction of duty, and that the Army and Navy chiefs on Oahu, General Walter C. Short and Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, had failed comprehensively in following orders and repelling the Japanese attack.

It should be understood, especially by those who were not around at the time, that there was no Defense Department in 1941, and no coordinated military operation as represented by the Pentagon today. The Army and Navy had separate secretaries in the Cabinet, and conducted their affairs separately unless, obviously, operating by agreement or under direction of the President. Each branch also had its own separate air forces. There had been talk for years before 1941 of consolidation into what was to become the Department of Defense after 1945. In congressional debate it had been posed as an economy move (“it will save many millions”), and there had been especially heavy debates on it in the House of Representatives in the spring of 1932. It was thought strange that the Hoover administration opposed it while at that moment creating a thunderous stir in admonishing Congress to balance the budget. (See the major roundup of US press sentiment on it in the lead story in the Literary Digest, May 21, 1932, pp. 5-6).

Major US Navy war ships in “battleship row” at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, settle to the bottom following the Japanese attack on the morning of Dec. 7, 1941.

Few realized that Justice Roberts (b. 1875), like the War and Navy Secretaries, Stimson and Frank Knox, respectively, was a Republican, appointed to the Supreme Court by Roosevelt's predecessor, Herbert C. Hoover, and had begun his Court service on May 30, 1930. (It was a disgrace for Congress later to conduct an investigation of Pearl on a partisan basis; the pro-war Roosevelt Democrats had as allies a very large contingent of pro-war Republicans, without whom FDR's war effort would have been impossible. The war homogenized the parties and turned the country temporarily into a one-party state.)

But nothing had been done by war's outbreak, so there is an aspect to the Pearl investigations that many today do not understand or appreciate: the rival views on responsibility with respect to the branches of the armed services, the defensiveness of both, and the partisanship among the politicians in ascribing more of the onus to one or the other, which fills the investigative reports and wearies the readers thereof. (In a caste society every caste becomes morbidly sensitive about its position, and this grows out of the possible change in esteem in which it is held, which may markedly alter that position. The armed forces certainly qualify as castes in this controversy.) .

The Army Pearl Harbor Board conducted its investigations in secret, listened to 151 testimonies and filed a secret report, which was made public after the end of the war in the summer of 1945, by which time Mr. Roosevelt was deceased and had been followed in office by Harry S. Truman, who was responsible for making this a public disclosure. At the conclusion of this investigation carried out from July 20 to October 20, 1944 – its finding became known almost immediately to Secretary of War Stimson, who put into operation the follow-up damage-control counter-investigation by his handpicked agent, Major Clausen, who in turn began his repair work less than five weeks later (Nov. 23, 1944). It is how this incredible operation was conducted which is the main subject of the book at hand, though it is fattened by an immense set of appendices which give it the appearance of greater formidability than it really has.

Attorney Clausen's final product was a masterpiece of self-serving (it constitutes Volume 35 of the subsequent Congressional investigation's published record), while adding a succession of glowing haloes around his adored chief, Secretary Stimson. One flees for balancing relief to Prof. Richard N. Current's Secretary Stimson: A Study in Statecraft (Rutgers Univ. Press, 1954, a frightfully neglected book), and a long succession of drastic discounting and appraisals of Stimson for various periods ranging from his performance as President Hoover's Secretary of State, 1929-33, to his central role as point man of the warrior Republicans who made FDR's War Deal such a triumph, 1940-45 et seq. (Mr. Stimson also served as Secretary of War in the administration of President William Howard Taft after his failure to become Governor of New York in 1910.)

Attorney Clausen and the historians would make a topic for a hundred thousand word essay. While claiming to have read them all, he considered them all ignorami, though producing no evidence whatever in support of this assertion. They in turn originally appraised attorney Clausen's mission as nearly worthless, and his attempt to derail the Army PH Report a weak and unconvincing diversion. What draws attention in his nearly 50 years after-the-fact dictum in Judgement is his savaging of Navy people on Pearl, which is really none of his business, while dodging entirely the Army responsibility for defending the Navy when it was berthed there. The work of 21 revisionists from John T. Flynn to John Toland (1945 to 1982) is 100 percent missing from Clausen's “final” dictum, and none of the other contemporaries are even worth mentioning. The ugly meanness of shrugging off all responsibility and splattering it all over underlings acting on the orders of these whitewashed superiors makes its mark on a reader with some perception of American traditions of fairness. One hesitates to say much in the presence of this shameful parade.

Before coming to any permanent conclusions a revisionist for sure needs to digest thoroughly five other basic treatments of it all, from contemporaries of Clausen to recent times. These are:

- the pertinent parts of Chapters 9 through 12 of Charles A. Beard's President Roosevelt (1948);

- the analysis of the Clausen mission by George Morgenstern in his Pearl Harbor (1947) and

- by Percy Greaves in his chapter on the Pearl Investigations in Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace (1953);

- the overall situation succinctly laid out in The Final Story of Pearl Harbor (1968) by Harry Elmer Barnes, and

- the assemblage of later-revealed important materials in John Toland's Infamy (1983 ed.).

All of Clausen's fuss and flapdoodle in getting people to alter their previous testimony about who saw, and when they saw the 13-part Japanese diplomatic message of the afternoon of December 6, 1941, is today just so much bound waste paper. What difference does it make what Army men did or did not see it after 6 p.m.? President Roosevelt certainly saw it by 10 p.m. that night and commented in the presence of witnesses, “This means war,” and in view of American-Pacific strength concentration in Hawaii that moment, FDR surely did not mean that Ottumwa and Kankakee were in danger. Why was nothing done for more than twelve hours after that? Stimson and Marshall were veritably at his elbow. Who besides the President was at the White House that night or most of that night? Does anyone know? Where was the chief executive of the Army, Gen. Marshall, for almost 24 hours after noon of Dec. 6, 1941? Clausen does not investigate these matters, but after all, as he repeatedly observed, he had not been appointed to investigate the investigators. And at no time did he claim to be a historian.

In the “case” of the Army PH Board vs. Stimson, Marshall et al it was hard to discern who were the plaintiffs and who the defendants, but Clausen performed mightily in behalf of the Administration figures. As a lawyer devoted to his client he was not interested in history. He was committed to making an ex parte collection of “evidence” or any kind of diversion which would redound to the credit of his adored chief Sec. Stimson, and hopefully at the same time discredit the APHB Report that implicated Stimson via Gen. Marshall for responsibility in failing to defend the US Fleet in Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, while at the same time planting the guilt once more, a la the Roberts Report, on the operational commanders at the scene, an ignoble and reprehensible stratagem if ever there was one.

This ancient game of saddling underlings for the responsibility when big plans and high strategy collapse and bring about disaster, was a sordid and unappetizing activity utterly lacking in basic decency. But it was the Army itself that had come down on Stimson and Marshall, after all, not some awful revisionists. (Atty. Clausen calls the latter “isolationists.”)

For someone who has gone over the substance of this work as often as this reviewer, much of this book is truly tedious. Perhaps this estimate of Clausen's book should have been done by someone utterly ignorant of it all, as had been the case with some of the newspaper reviews, in which case they might have been able to approach the assignment with some kind of breathless sense of discovery.

There is no use to pile example upon example, but one might mention the famed “war warning” to Gen. Short of Nov. 27, 1941, about which a veritable library of analysis and comment exists. Beside what is at hand, revisionists should surely examine this set of contradictory advisories in Chapter 8 of Prof. Current's Secretary Stimson, “The Old Army Game,” and Chapter 16 of Morgenstern's Pearl Harbor, “The 'Do-Don't' Warnings.”

How Gen. Short could put the base on a semi-attack alert and a sabotage alert simultaneously, conduct long range reconnaissance by air without planes of flying range to do the job, and how he could encompass other precautions without unduly exciting and arousing the civilian population of Honolulu surely tax almost anyone's sense of the rational. For instance, there was the major coastal artillery base, Fort DeRoussy, not at Pearl but six or more miles away, smack up on the fringe of the big resort hotels on Waikiki Beach. How Gen. Short could have sent in a fleet of Army trucks loaded with shells to arm these big guns without creating a mild hysteria among the Honolulu civilians, who could not have missed witnessing all this, escapes all understanding.

And if Clausen had made even the barest effort at keeping abreast of what had been done on the subject other than by himself, he and his co-author could have saved themselves the embarrassment of the final appendix to their book, “The 'Winds Code'” (pp. 447-470). This reprinting of what the politicians had done to Capt. Safford as the lasting line on the “East Wind, Rain” message is almost beyond comment. Those in the congressional hearings who mauled Safford repeatedly for his stubborn insistence such a message had been received at least three days before the attack on Pearl conducted what was probably the ugliest and most dishonest campaign ever carried out in public against a member of the US armed forces. It is very likely that at least one of them knew such a message had been received, and probably that there had been several other receptions.

The question of whether Capt. Safford had received this message or not is central to the most sacrosanct Establishment tome on Pearl, Roberta Wohlstetter's Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision (1962). However, this matter was blown away more than 15 years ago by the revelations of Navy Warrant Officer Ralph T. Briggs, who was responsible for getting the copy to Capt. Safford. (It was Safford who was responsible for keeping the role of Briggs concealed and thus saving his career from destruction.) This is gone over repeatedly by Toland in his book Infamy.

US and Soviet Intelligence in Pre-Pearl Japan

For a quarter of a century this writer has been aware of a buried theme in Pearl Harbor revisionism that so far has had virtually no written accompaniment. Itis a mixture of suspicion and conviction that the United States via one or another of its civilian agencies or armed forces had a formidable intelligence service planted in Japan, perhaps for a decade before December 7, 1941, and knew well in advance of the usual official line on the subject when the Japanese fleets left port to bring their air force to bomb Pearl, and to attack and invade the Philippines two days later.

The Soviet Union had such an operation, as those who have read one or another of the many accounts of Richard Sorge may recall. Japan had a well-disciplined Communist Party founded in part by the legendary Sanzo Nozaka (1892-1993) as far back as 1922. He had spent most of the war years involving Japan and China at the headquarters of Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communists in Western China. In fact, the Stalinist spy ring had even been successful in planting a Japanese Red, Hotsumi Ozaki, in the Japanese Cabinet itself. It is most unlikely that only Stalinist Russia had a spying operation in Japan.

In the lengthy, almost-400 word footnote by Toland on p. 272 of the 1983 Berkley Books edition of his Infamy dealing with Major (later Colonel) Warren J. Clear, head of US Army Intelligence in the Far East, there were observations leading one to conclude that US Army Intelligence was anything but ignorant about what was going on in Japan in the fall of 1941. But nothing was said about how information was being gathered, which brings up something more substantial relative to Col. Clear.

In 1968 an amateur cryptologist enthusiast, David Kahn, published a widely-circulated book titled The Gode Breakers, which included material about Pearl. Editors assumed that he was an expert. In a piece published more than a dozen years later, Kahn made the flat-out statement, “The United States had no spies in Japan.” When this article was reprinted in the San Francisco Chronicle of Dec. 7, 1981, it prompted a retired US Army Colonel, John W. Carrothers, to write in denunciation of this as one of the “damn lies” the paper had printed on Pearl that day. In the conclusion of his letter to the editor, published Dec. 11, 1981, Carrothers went on to report on an address he had heard Col. Clear deliver to “900 officers at the Command and General Staff School,” which concluded with the following words by Clear:

I had an excellent organization in Japan. It consisted largely of Koreans, who hated the Japanese because Japan was then occupying their country. Regarding the Japanese army which invaded the Philippines, I knew the designations and strengths of the units, the names of the ships on which they were to sail, the dates of departure, the names of the ports of destination in the Philippines. All of this information was on President Roosevelt's desk 48 hours before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

In mulling over this declaration there has been a revisionist assumption that if US Army Intelligence had a full detailed report on the Japanese Navy task force which had departed for the Philippines, was it not logical to conclude that the same Korean dock-worker spies had also furnished the details on the Hawaii-bound fleet that had sailed out a few days earlier? Perhaps this might have been taken up in the book Col. Clear was writing about Pearl Harbor (Toland gives the title as Pearl Harbor: The Price of Perfidy), but it was never published and the manuscript disappeared after the demise of the author in 1980. This was the fate of another Pearl Harbor book that never saw print, produced by US Navy (Ret.) Commander Charles C. Hiles. It also vanished after its author's death. From what had been said about them informally, the Clear and Hiles books “contained dynamite,” as the expression goes. So the situation remains a conflict between the will to believe, encouraged by books such as that by Atty. Clausen, as against the desire and determination to find out, as reflected by the ongoing search by revisionists.

– J.J.M.

It was amazing how quickly attention to this was jettisoned after the publication of the substance of the Briggs interview by the Establishment American Committee on the History of the Second World War in its Newsletter No. 24, which appeared about Christmas of 1980. And one ought to re-read the solid tribute to Capt. Safford by Percy Greaves in The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 4, no. 4 (Winter 1983-84).

But it is not just revisionists who have clawed Atty. Clausen. Even the olympian-based Mrs. Wohlstetter, whose 1962 book was the bible on Pearl in Establishment Academe, scorned Clausen, describing his 1945 Report as “notoriously unreliable” (Wohlstetter, p. 35). Clausen's chief supporter among Establishment authors of major works on Pearl was Ladislas Farago in The Broken Seal (1967, p. 416) who praised it and him without any reservation.

The title of the book, Pearl Harbor: Final Judgement, is both preposterous and insulting if not laughable. It is the last work on the Pearl Harbor drama about like yesterday's sunset was the culmination of the world. It sounds like the similar pontifical titles of the glosses on the work of Gordon Prange by the team of Profs. Goldstein and Dillon; “The Verdict of History,” indeed. (On Prange's shortcomings as a historian one should consult the critique by Capt. Roger Pineau, USN (Ret.) which covers more than an entire page in the Christian Science Monitor of Dec. 7, 1982). No number of works with absurd and arrogant titles alleging to be the “verdict of history,” the “final judgement,” and the like will ever stem Pearl Harbor revisionists from coursing the trail to the White House in the fall of 1941, instead of to the armed forces commanders at Hawaii, who were under direct orders of the civilian and armed forces quintet in Washington headed by the President.

It would be the epitome of softness to label Atty. Clausen's operation, a 55,000 mile trip around the world at taxpayers' expense at the direction of, and for the benefit of only one man, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, “one sided.” In seeking to vindicate his revered chief's evasion of responsibility while choosing the deplorable ploy of passing on the buck to subordinates, Clausen performed mightily. His sweet and deodorized treatment of Sec. Stimson through this report is, however, in near polar opposition to, for example, the civilized dismantlement of Stimson by Prof. Current in the book mentioned above. (Commenting on Clausen's boast of having interviewed 92 persons in the course of his investigation, and including quotations from 50 of them in his report, Greaves remarked in Perpetual War, p. 434: “But there was no word as to what he learned from the other forty-two.”) One would think from Clausen's skewed myopic view of it all that absolutely nothing happened between 1945 and 1992.

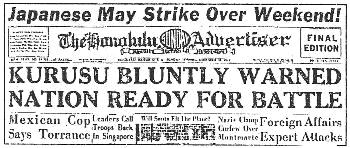

“Japanese May Strike Over Weekend!” announces a front-page headline in a leading Hawaii daily paper, The Honolulu Advertiser, Sunday, Nov. 30, 1941, one week before the Pearl Harbor attack.

Nevertheless, this effort a near half-century after to capitalize on it all does not clear the contemporary record. Greaves, in Perpetual War (pp. 43339) characterized Clausen's odyssey as probably the greatest whitewash job ever essayed upon in history, while Morgenstern in Pearl Harbor (p. 200), written in 1946, concluded that if there was a single person in the USA primarily responsible for there being a thick miasmic cloud of utter irrelevancy making it impossible to sort out the Pearl Harbor story because of his numerous false leads and pointless wild goose chases, it was Henry C. Clausen. (On Sec. Stimson's integral Big Money ties one should consult Ferdinand Lundberg, America's 60 Families [New York: Vanguard, 1937]. Though a failed candidate for high office in 1910 and a one-time district attorney, Mr. Stimson was essentially always a Wall Street lawyer, equally at home in the cabinets of Presidents both Republican and Democrat.)

Henry C. Clausen spent well over a generation tending to the legal affairs of the Scottish Rite Masonic order, in which he became a Sovereign Grand Commander and honored by the designation “Illustrious.” Turning to the subject of theology in the 1970s he produced a work titled Clausen's Commentaries on Morals and Dogma, which before the end of that decade sold almost a quarter of a million copies and surely has pushed toward the half-million mark since. It was first published under the authority of the Supreme Council of the Scottish Rite in San Diego in 1974. In view of his substantial reputation among his Masonic confreres in this area of endeavor, it is probably unfortunate that Atty. Clausen did not stick to theology instead of participating in a recycling of his role in the Pearl Harbor smokescreen.

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 15, no. 1 (January/February 1995), pp. 39-43

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a