His Master’s Voice

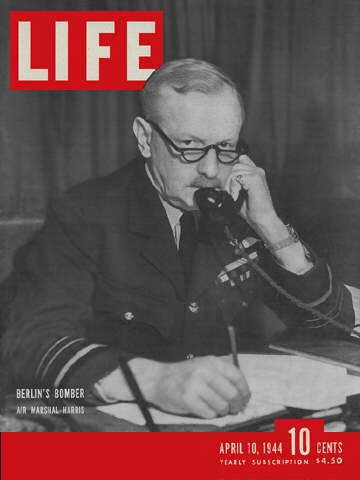

Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Travers Harris, 1892-1984

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley

“Bomber” Harris died on 5 April of this year, at the age of 91. As Air Officer Commanding in Chief Bomber Command from February 1942 until the end of the Second World War, he was in charge of Britain’s massive “area bombing” campaign directed against German cities. At least half a million German civilians were killed in these raids. And over 58,000 British air crew members died while flying in massed concentrations of heavy bombers – nearly the same number of fatalities suffered by British junior army officers during the First World War. The British jurist and historian, F. J. P. Veale, considered this “an even more calamitous loss since the standard of health and intelligence required for the men of Bomber Command was far higher than that of the junior officers who served in the trenches in France twenty years before.”

English by birth, Harris spent part of his youth in Rhodesia. After joining the British Army, he transferred to the Royal Flying Corps, which was redesignated the Royal Air Force in 1919. He commanded bomber and transport squadrons in Britain and the Mideast and by 1938 was Air Officer Commanding in Palestine and Transjordan. The next year he took command of No. 5 Bomber Group in Britain, which post he held until 22 February, 1942, when he was entrusted with the direction of Bomber Command.

Harris took command of Britain’s strategic bombing effort when the new four-engine heavy bombers were beginning to roll out of the factories. The Lancasters and Halifaxes were the principle delivery vehicles employed to drop thousands of tons of bombs on German cities.

Britain, like the other combatants, had attempted precision bombing of military targets early in the war. The 1941 British “Butt Report,” dealing with the effectiveness of bombing, found that only 30 percent of the bombers arrived within five miles of their targets, and in the Ruhr only 10 percent. Unable to engage in precision bombing, Harris advocated and instituted “area bombing.” This technique required the assembly of very large numbers of bombers, which would then drench whole metropolitan areas with high explosives and incendiaries. The aircraft were directed toward the center of a given city, since they were unable to strike selectively military targets. It was presumed that amid all the destruction wrought some targets of military significance would be demolished. During the process of hitting a city, factory workers and other civilians would, of course, be killed and wounded, with thousands more “de-housed.” Harris and other advocates of area bombing argued that such a bombing campaign would bring the war to a relatively swift end, by doing massive material and morale damage to the enemy.

Harris launched the first of his famous “Thousand Plane” raids against Cologne on 30 May 1942. While much favorable publicity was generated, the actual military results were exaggerated. For the year 1942, German armament production increased 50 per- cent overall, with aircraft output way up and oil, Germany’s weakest link, hardly touched. This armament increase came despite the intensification of the British and American bombing campaign.

Area bombing continued. On 12 August 1943, Harris wrote to Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal: “It is my firm belief that we are on the verge of a final showdown in the bombing war… I am certain that given average weather and concentration on the main job, we can push Germany over by bombing this year.” He followed up this prediction with another in January 1944, declaring that if he were only permitted to stay the course, his bombing campaign would drive Germany to “a state of devastation in which surrender is inevitable” by April 1st of that year.

Even as Harris was forecasting imminent victory through bombing, Bomber Command was fighting for its life over the skies of Germany. From November 1943 to March 1944, the RAF conducted the air Battle of Berlin. During this campaign the British lost 1,047 bombers, with a further 1,682 damaged – many beyond repair. The last blow came with the catastrophic Nuremberg raid of 30 March 1944, when the British suffered the loss of 94 bombers and another 71 damaged, out of 795 sent out that night. The severe losses in men and aircraft placed the future of Harris’ massed night attacks in doubt. But his command was given a reprieve when he was ordered, over his vigorous protests, to switch to operations directed against the French rail network, in order to assist the forthcoming cross-Channel invasion at Normandy.

Throughout the Summer of 1944, Harris called for the resumption of massed attacks against German cities. He even threatened to resign when given a directive, dated 25 September 1944, recommending that Bomber Command concentrate against oil and communications targets. On 27 January 1945 Harris was explicitly instructed to resume terror attacks against the German civilian population. This led to the notorious mid-February raids on Dresden, by then overflowing with refugees from the Red Terror in the East.

Harris was certainly one of the dominant military figures of the Second World War. However, the bombing campaign he had directed became an unpopular topic – especially among politicians – after the war. Harris left his post in September 1945, never to be given another military command by the British. He was the only top British military commander not given a peerage at the end of the war, and Bomber Command was denied a separate campaign medal and separate church monuments. Members of the Royal Family turned down invitations to its reunions. The British Government even refused to permit Harris to consult official records when writing his war memoirs. For many years after the war he worked in private business in South Africa.

It is noteworthy that Harris’ civilian superiors largely succeeded in escaping responsibility in the public mind for the policy of bombing German cities instead of concentrating on military targets. The decision to bomb cities for morale effect was made long before Harris became Commander-in-Chief of Bomber Command. The official minutes (quoting participants in the third person) of the War Cabinet meeting of 28 October 1940 reveal that Churchill said:

… whilst we should adhere to the rule that our objectives should be military targets, at the same time the civilian population around the target areas must be made to feel the weight of the war. He regarded this as a somewhat broader interpretation of our present policy, and not as any fundamental change. No public announcement on the subject should be made. The Italians and, according to recent reports, the inhabitants of Berlin, would not stand up to bombing attacks with the same fortitude as the people of this country. (Public Records Office – Kew, file PRO 65/6 War Cab 280 (40), 30 October 1940.)

On 14 February 1942, a week prior to Harris’ new appointment taking effect, the British Cabinet issued a new directive to Bomber Command that ordered the bombing campaign to “be focused on the morale of the enemy civilian population and in particular the industrial workers.” That was to be Bomber Command’s “primary object.” “Thus,” as B. H. Liddell Hart observed, “terrorization became without reservation the definite policy of the British Government, although still disguised in answer to Parliamentary questions.” After all, as Churchill remarked, “There are 65 million Germans – all of them killable.”

Reflecting on the terror bombing campaign, the famous British military strategist and historian, General J. F. C. Fuller, felt that “Bomber” Harris was symptomatic of a general decline in British character and morality: “With the disappearance of the gentleman – the man of honour and principle – as the backbone of the ruling class in England, political power rapidly passed into the hands of demagogues, who by playing upon the emotions and ignorance of the masses, created a permanent war psychosis. To these men, political necessity justified every means, and in wartime, military necessity did likewise.”

Air Marshal Sir Arthur Harris was truly a man of his times.

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 5, no. 2, 3, 4 (winter 1984), pp. 431-434

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a