Imprisoned at Ellis Island

Editorial

On December 23, 1991, President George H. W. Bush issued proclamation 6398 to recognize National Ellis Island Day. His proclamation began:[1]

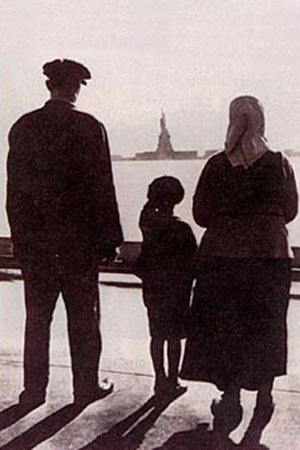

“The ethnic diversity that we so proudly celebrate in the United States mirrors our rich heritage as a Nation of immigrants. ‘Here is not merely a Nation,’ wrote Walt Whitman, ‘but a teeming nation of nations. […] Here is the hospitality which forever indicates heroes.’ One of the greatest symbols of American hospitality stands at Ellis Island in Upper New York Bay.”

Bush went on to call America’s history, “a story of immigrants.”[2] Indeed, according to the Ellis Island Website, “Ellis Island is the symbol of American immigration and the immigrant experience.”[3] There can be no doubt that Ellis Island has become a part of the contemporary American mythos. There is an incredible irony however about this symbol of hospitality and liberty — Ellis Island was used as a detention center for Germans and Italians during the Second World War.

In a stark example of inconvenient history, an investigation into the use and function of the facility at Ellis Island undoubtedly results in critical questions about our freedoms, our conduct of war, and even the treatment of ethnic and religious minorities by Americans.

Ellis Island, a small island in New York Harbor, was designated as the site of the first Federal immigration station by President Benjamin Harrison in 1890.[4] It officially opened its doors on January 1, 1892. Ellis Island became the nation’s premier federal immigration station. It remained in operation until 1954. During this time, the station processed over 12 million immigrant steamship passengers. The island was made part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument in 1965, and has hosted a museum of immigration since 1990.[5] The main building was restored after 30 years of abandonment and opened as a museum on September 10, 1990.[6]

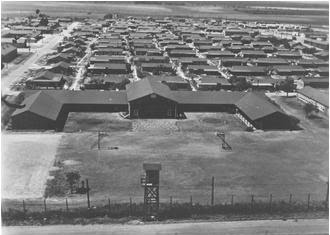

During the 1940s however, Ellis Island served another purpose—it was the location of an internment camp that held about 8,000 German, Italian, and Japanese U.S. citizens, naturalized citizens, and resident foreigners.[7] Ellis Island also served as a way station for those being transferred to and from other internment camps and for those awaiting deportation, repatriation, or expatriation.[8] At the time, Ellis Island was the perfect prison – easily guarded and reachable only by boat.

While the story of the internment of Japanese-Americans has become more widely known, it remains a largely untold tale that Germans and Italians were interned in at least forty-six locations in the United States during World War Two including Ellis Island.[9]

The majority of aliens arrested in New York and New Jersey were first taken to Ellis Island. According to a 2003 New York Times article:[10]

“Letters show that the Attorney General’s office expected to arrest 600 people from New York and 200 from New Jersey per month and hold them on Ellis Island. On Dec. 8, 1941, the day after the [Pearl Harbor] attack, the roundup began. Internees were housed in the baggage and dormitory building behind the Great Hall.”

The Ellis Island Reception center held people whose loyalty was in question. Of those interned, there was evidence that some had pro-Axis sympathies. Many others were interned based on weak evidence or unsubstantiated accusations of which they were never told or had little power to refute. [11] During the first two years of the war, Ellis Island was used primarily as a transit and holding camp. By January 1943, the population of German internees had stabilized at about 350 enemy aliens and their dependents. Upon arrival prisoners would have their clothes replaced with a pair of American army shoes, khaki socks, shirt, and underwear.

How did this come to pass?

In 1940, the Alien Registration Act was passed requiring all aliens aged 14 and older to register with the US government. On Dec. 7, 1941, pursuant to the Alien Enemy Act of 1798, Roosevelt issued three Presidential Proclamations 2525, 2526 and 2527 branding German, Italian and Japanese nationals as enemy aliens, authorizing internment and travel and property ownership restrictions. A blanket presidential warrant authorized U.S. Attorney General Francis Biddle to have the FBI arrest a large number of “dangerous enemy aliens” based on the Custodial Detention Index. Hundreds of German aliens were arrested by the end of the day. The FBI raided many homes and hundreds more were detained before war was declared on Germany on December 11.[12]

On January 14, 1942, the Attorney General issued regulations pursuant to Presidential Proclamation 2525-2527 and 2537 requiring application for and issuance of certificates of identification to all “enemy aliens” aged 14 and older and outlining restrictions on their movement and property ownership rights. Approximately one million enemy aliens reregistered, including 300,000 German-born aliens, the second largest immigrant group at that time. Applications were forwarded to the Department of Justice’s Alien Registration Division and the FBI. Any change of address, employment or name had to be reported to the FBI. Enemy aliens were prohibited from entering federally designated restricted areas. If enemy aliens violated these or other applicable regulations, they were subject to “arrest, detention and internment for the duration of the war.”[13]

U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued the now infamous Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942 authorizing the Secretary of War to prescribe certain areas as military zones. Eventually, EO 9066 cleared the way for the incarceration of Japanese Americans, as well as Italian Americans and German Americans in internment camps. In total, 10,905 people of German ancestry were interned, along with 3,278 people of Italian ancestry not counting spouses and children who voluntarily joined internees.[14] [15]

While the United States has officially apologized for its treatment of Japanese-Americans for their relocation and imprisonment during the war, we are apparently reluctant to apologize to the German and Italian internees. President Gerald Ford rescinded Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1976. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter signed legislation to create the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC). The CWRIC was appointed to conduct an official governmental study of Executive Order 9066, related wartime orders, and their impact on Japanese Americans in the West.

In December 1982, the CWRIC issued its findings in Personal Justice Denied, concluding that the wholesale incarceration of Japanese Americans had not been justified by military necessity. The report determined that the decision to incarcerate was based on “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” The Commission recommended legislative remedies consisting of an official apology and redress payments of $20,000 to each of the survivors; a public education fund was set up to help ensure that this would not happen again (Public Law 100-383).

On November 21, 1989, President Bush signed an appropriation bill authorizing payments to be paid out between 1990 and 1998. In 1990, surviving internees began to receive individual redress payments and a letter of apology. This bill only applied to the Japanese Americans. German Americans and other European Americans received neither the apology nor the recompense.[16]

While there was no evidence of a military necessity for the incarceration of German, Italian, or Japanese Americans during World War Two, we are faced with a similar situation today, only this time with Arab and Muslim internees. President Obama came into office in 2009 promising to shut down the Guantanamo Bay detention camp and end the extra-judicial system that President George W. Bush had created to imprison terrorist suspects without trial, often without even filing charges.

On New Year’s Eve 2011, President Obama signed his name to the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012. Buried in this act are provisions that appear to allow indefinite military detention of American terrorism suspects, and to require it of suspected foreign enemies. The Obama administration insists the law merely codifies existing standards, but its strong supporters and vehement opponents are sure it does much more, legally enshrining for the first time in 60 years the authority to hold citizens without trial.[17]

Americans like to think of the Second World War in strict terms of good and evil. It is difficult to consider that our political leadership was making decisions based on “race prejudice” and “war hysteria.” And yet that was the determination of the CWRIC. When will the lessons of the past be applied to contemporary political events? When will we realize that the Greatest Generation was not so different from our own—complete with blemishes and warts. It is quite simple to criticize and attack the actions of the vanquished – long dead enemies and regimes. It is far more difficult to realize that history is always written by the victors.

Notes:

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 4(3) (2012)

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a