Jan Karski’s Visit to Belzec

A Reassessment

“Claude Lanzmann: There are no survivors of Belzec.

Jan Karski: There are a lot of them!”

“One man who tried to stop the Holocaust.” “The first witness to the Holocaust.” Superlatives have never been lacking in descriptions of the Polish courier Jan Karski. His celebrity has extended to academia, where much ink has been spilled over such questions as whether Karski was on a mission to save the Jews (he was not) or whether he played an important role in informing the Allies about the alleged extermination of the Jews (he did not). Yet the actual contents of Karski’s witness account have generally been relegated to the background, to be “dealt with” briefly and then forgotten once more. On the traditional view, Karski’s story is as follows: Jewish leaders, having learned of Karski’s impending mission to London, asked him to carry a message for the Jews as well as for the Poles. They smuggled him into the Warsaw ghetto and into the Belzec “death camp” so that he could act on their behalf as a direct eyewitness. He then “became one of the first eyewitnesses to present to the West the whole truth about the fate of the Jews in occupied Poland.”[1]

As Karski described his experience at Belzec, he had seen a transport of Jews being driven out of the camp, down a narrow passage, and onto a waiting train. On that train, they would “die in agony,” killed by the disinfectant which had been spread on the floors of the wagons. Some time later, the train having meanwhile traveled to a remote location, their bodies would be removed and disposed of.[2]

Gradually, certain historians developed reservations about the story of Karski’s visit to Belzec. The camp, after all, was supposed to have been a killing center equipped with homicidal gas chambers. All Jews sent there were supposed to have been killed in those chambers, less a few who were kept alive to work in the camp. And transports of Jews were certainly not supposed to have departed Belzec, whose status as an extermination camp was to be proved by the fact that transports of Jews continually arrived at, but never departed, the camp.

Source: By commons: Lilly M pl.wiki: Lilly M real name: Małgorzata Miłaszewska-Duda [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

“Above all, trains did not leave Belzec or Treblinka[3] so that the passengers could die in the cars. Belzec and Treblinka were death camps with gas chambers, and these facilities were not mentioned in Karski’s account.”

The response to this troublesome witness was complicated by the fact that Karski had been hailed as a hero and savior of Jews. He had been named “Righteous Among the Nations” and made an honorary citizen of Israel. To call him a liar would be politically inconvenient. A more elegant solution was needed, and was found: Karski had not visited Belzec, but the Izbica transit ghetto, where he witnessed a deportation to Belzec. Thus altered, Karski’s observations would no longer contradict the standard Holocaust storyline. This account was promoted by Karski’s biographers Thomas Wood and Stanislaw Jankowski[5] and rapidly gained general acceptance. Although some historians continued to repeat the older story,[6] the triumph of the new version was so complete that when Karski was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012, the official announcement stated that Karski had “worked as a courier, entering the Warsaw ghetto and the Nazi Izbica transit camp, where he saw first-hand the atrocities occurring under Nazi occupation” without mentioning Belzec at all.[7]

This paper will show that the thesis that Karski visited Izbica and witnessed the deportation of a transport of Jews is certainly false, and will explain the features in Karski’s reports which have been used to support the thesis of a visit to Izbica. Furthermore, it will show that Karski’s accounts contain information that can only have come from an actual visit to Belzec. Both revisionist and orthodox writers have adduced arguments against Karski’s alleged visit to Belzec.[8] These too will be addressed in due course, and shown not to give any reason to doubt that the visit occurred.

1. Karski’s Chronology

In order to clarify the circumstances surrounding Karski’s visit to Belzec, we must first clarify when it happened. The outline of Karski’s story is as follows: in Warsaw he met with Jewish leaders, who smuggled him into the Warsaw ghetto (twice), and some days later into the Belzec camp. Later he traveled to London as a courier for the Polish government in exile, where among other things he reported on the situation of the Jews. When did this happen? Karski arrived in Britain on November 25, 1942,[9] and was detained and interrogated at the Royal Patriotic School, leading to some minor diplomatic kerfuffle.[10] In his book Story of a Secret State, Karski boasted that his entire trip from Warsaw to London lasted only 21 days,[11] and dated his conversation with Jewish leaders to the beginning of October,[12] his visits to the Warsaw ghetto and Belzec occurring after that.

A number of authors have accepted this date and thereby been led into confusion, for this chronology, which served to emphasize the swiftness of Karski’s trip, is false. As Karski’s biographers Wood and Jankowski observe, there are documents recording Karski’s departure from Warsaw by October 2nd and his arrival in Paris by October 6th.[13] Clearly this rules out the above mentioned chronology. More recent scholarship has suggested that Karski left Warsaw between September 12th and 19th.[14] An earlier report of Karski’s story in the Jewish publication The Ghetto Speaks dates the visit to the Warsaw ghetto to August and the Belzec visit to late September.[15] An even earlier and generally overlooked source – which will be discussed in greater detail below (Section 3) – dates those two visits to August and September.[16]

Karski’s description of his conversation with Jewish leaders in Warsaw shows that he visited the Warsaw ghetto after the first wave of deportations, probably during the brief halt that occurred in late August and early September.[17] The date of Karski’s departure from Poland shows that the Belzec visit can on no account be dated any later than September. While The Ghetto Speaks dates it to late-September, this is part of a stretched-out chronology that places Karski in Poland until late October, nearly a month too long. Cutting the timeframe down to the proper size would move Karski’s visit to early September, which is the most probable date.

2. The Izbica Thesis

As previously discussed, Karski’s statements that he had seen Belzec as a transit camp, coupled with his newfound celebrity, put traditionalist Holocaust scholars in an uncomfortable position. Accepting that Belzec actually was a transit camp was out of the question. Calling Karski a liar was politically inconvenient, and would set a dangerous precedent. Consequently, they elected not to reject Karski’s story altogether, but to change his destination. The location they seized on was Izbica, a Jewish town located between Belzec and Lublin.

The principal support for their argument was that some versions of Karski’s story from 1943 describe a visit to a camp a certain distance from Belzec, and distinct from the Belzec camp itself. As they interpreted the texts, the visit to Belzec was only a late addition to his story. As Karski’s biographers E. Thomas Wood and Stanislaw Jankowski put it:[18]

“The village Jan reached was not Belzec, nor did Jan think it was while he was there. When he first spoke of this mission after reaching London three months later, he described the site as a ’sorting point’ located about fifty kilometers from the city of Belzec – although in the same statement he referred to the camp’s location as ‘the outskirts of Belzec.’ (The actual Belzec death camp was in the town of Belzec, within a few hundred feet of the train station.) In an August 1943 report, Karski at first placed the camp twelve miles, then twelve kilometers outside of Belzec. By the time he began retelling his story publicly in 1944, the town he reached had become Belzec itself. […]

Jan was in the town of Izbica Lubelska, precisely the midway point between Lublin to the northwest and Belzec to the southeast – forty miles from each locality. Izbica was indeed a “sorting point”; Karski had this fact right and the distance from Belzec nearly right in his earliest report.”

The claim that the destination of Karski’s visit was in fact Izbica is taken for granted in the more recent literature.[19]

However, as we have seen, Karski’s visit to Belzec – or, on the new understanding, to Izbica – can be dated to September, most likely early September. Is it possible that Karski visited Izbica at that date and saw a transport being loaded with Jews?

If this were to be true, the first requirement would clearly be that there actually was a transport departing Izbica at around this date. Consultation of standard sources readily confirms that there was not. The lists of transports in Yitzhak Arad’s standard book on the Reinhardt camps contains no transports departing Izbica between May 15 and October 22, 1942.[20] A more recent list of all transports to and from Izbica contains some transports missing from Arad’s book, but confirms that no transport departed Izbica at any time even approximating the date of Karski’s visit.[21] Thus, the Izbica thesis fails on simple matters of chronology. Jan Karski cannot have visited Izbica and witnessed a transport of Jews being loaded to depart, because no transports of Jews departed Izbica at the time he allegedly visited. In contrast, Belzec was at the peak of its activity at the time of Karski’s visit.

While the fact that Karski’s description of his experience does not match the reality of Izbica in time is sufficient to refute the Izbica thesis, it is worth observing that his description does not match the reality of Izbica in place either. Karski’s descriptions of the camp he visited consistently maintained that it was entirely fenced in. For example, in the 1943 pamphlet Terror in Europe, Karski’s account describes the camp as “bounded by an enclosure which runs parallel to the railway track”,[22] and his 1944 book Story of a Secret State elaborates that it was “surrounded on all sides by a formidable barbed-wire fence” and well-staffed by guards.[23] Izbica, however, was not a closed ghetto. It was surrounded neither by walls nor barbed-wire fences.[24] Therefore Karski’s account cannot be of Izbica.

Looking at Karski’s full story makes the geographic contradiction between Karski’s story and Izbica even clearer. As Karski described his trip, he took the train to a town from which the Jews had been removed. There he met his contact, a Belzec guard, with whom he walked to the camp. The geography of Karski’s story, therefore, consists of an Aryan town and a nearby fenced-in camp that dealt with Jews. This matches the reality of Belzec Town and Belzec Camp. It does not match the reality of Izbica, which was an almost entirely Jewish settlement. As the Izbica native Thomas Blatt described it, Izbica was a “typical shtetl” with a prewar Polish population of only two hundred,[25] where Jews and Poles lived together even during the war.[26] Robert Kuwalek quotes a Jew who was deported to Izbica and described it as not a ghetto but “a purely Jewish town where no Poles lived”.[27] While Kuwalek notes that this statement is inaccurate, as “several dozen” Polish families lived in Izbica at that time, the description nevertheless illustrates just how dramatically different Izbica was from the town which Karski described visiting. Karski visited an Aryan town with a nearby fenced-in camp, while Izbica was an unfenced Jewish town without a nearby fenced-in camp. The two could hardly be more different.

We have seen that the Izbica thesis is impossible on both chronological and geographical grounds. Moreover, the internal logic of Karski’s story contradicts the idea of a visit to Izbica. As he described his visit to Belzec/Izbica, it was arranged by the Jewish underground, who wished to show him the full extent of the persecutions of the Jews so that he could speak in their cause as a direct eyewitness when he arrived in London. Therefore they decided to send him to Belzec, which they had identified as an extermination camp. Jewish organizations had in fact identified Belzec as an extermination camp, but they had made no such identification of Izbica. For Jewish leaders to wish to obtain a witness to Belzec, which they conceived as an extermination camp, is perfectly logical. According to one report, the Jews had sought a witness to Belzec exterminations as early as April 1942, and were willing to pay any witness who would give such testimony.[28] Their motivation for desiring a witness to a seeming extermination camp is understandable, but given that Karski had already seen the Warsaw ghetto, there was no reason for them to exert themselves in sending him to see the Izbica ghetto.

Nor does it make sense that Jewish leaders would arrange a trip to Izbica for Karski while telling him that he was going to Belzec. Even the possibility that Karski might have ended up visiting Izbica by mistake in spite of the fact that a visit to Belzec had been arranged is ruled out by the fact that Karski describes making a prearranged rendezvous with a Belzec guard, which would have been impossible in the event of a mistaken location or a last-minute change in plans. It is also unlikely that Karski could have been seriously confused about his location. As one author has stated, “[s]ince Karski was very familiar with Polish geography, it is difficult to see how he could have erred.”[29] Karski knew the area well. He had attended the University of Lvov, just 45 miles from Belzec.[30] In December 1939, he had seen an earlier camp for Jews located near Belzec. He had described this camp in a 1940 report, and mentioned the town of Belzec by name, correctly locating it “on the boundary of the territories occupied by the Bolsheviks.”[31] The supposition that he confused Belzec with Izbica is far-fetched.

Although the preceding arguments easily show that the Izbica thesis is totally untenable, they still leave some questions unanswered. Was the location of Belzec really a late addition to Karski’s story? Why are there versions of Karski’s story that describe visiting a “sorting point” rather than Belzec? Finally, did Karski really go to Belzec or did he not? The remainder of this paper will answer these questions.

3. The Earliest Report of Karski’s Visit

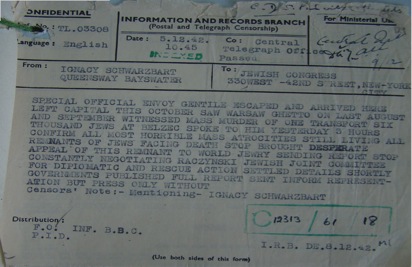

Authors supporting the Izbica thesis have supposed that Karski’s first accounts describe a visit to a camp some distance from Belzec. This claim is refuted by a telegram sent by Ignacy Schwarzbart, one of the two Jewish members of the Polish National Council, the day after he met with Karski.[32] The telegram, which was preserved because it was copied by the British censors,[33] has been largely ignored, despite its obvious importance.[34]

The telegram records a three-hour meeting the previous day[35] between Schwarzbart and a special official envoy gentile, evidently Jan Karski, who told Schwarzbart about visiting the Warsaw ghetto in August and in September visiting Belzec where he witnessed mass murder of one transport of six thousand jews.

The telegram confirms that Karski reported visiting Belzec from the beginning. Therefore, the chronological sequence of accounts of Karski’s trip is not

visit to a “sorting point” some distance from Belzec → visit to Belzec

but

visit to Belzec → visit to a “sorting point” some distance from Belzec → visit to Belzec

Below, we will be concerned with explaining this sequence of accounts.

The Vanishing Meeting

In an important article on Karski’s mission, David Engel has argued that the courier did not meet with Ignacy Schwarzbart until months after arriving in London. Engel’s principal argument was that Schwarzbart’s diary does not mention Karski until March 16, 1943, and then only for a remark about the relative positions of the Jews and Poles, not as the source of any vital new information.[36] If an incidental remark from Karski was enough to cause Schwarzbart to make a note in his diary, Engel reasoned, then a meeting with Karski revealing the truth of extermination at Belzec would certainly have provoked the same response.

Schwarzbart’s silence caused Engel to doubt that Karski had bothered to contact Jewish leaders at any earlier date. In light of Schwarzbart’s telegram shown above, his diary’s months-long silence about Karski takes on quite a different significance. Why did Schwarzbart not record his meeting with Karski in his diary? His telegram shows that it was of great importance to him at the time. Given that his diary does record an unimportant remark Karski made some months later, why is it silent on such a momentous meeting?

4. Some Background

Our next aim is to determine why there are accounts of Karski’s trip which put him in a “sorting point” far from Belzec. In order to solve this problem, we will need to look at the full array of wartime sources for Karski’s story. Before we do this, however, it will be useful to step back and consider the broader context. Who was Karski? What were his goals, and what problems did he face? Or more to the point, what were the goals and problems faced by the Polish government in exile?

Any general account of Karski’s context must start with the government which he served. As a result of the diplomatic posture they had taken prior to the war, the Poles found themselves in opposition to both Germany and the Soviet Union. While opposition to Germany fit comfortably with their position among the minor allies, opposition to the USSR involved a conflict within the Allied camp. While the Poles, under heavy pressure from the British, grudgingly reestablished diplomatic relations with the Soviets on July 30, 1941, they had no intention of giving up the territories that the Soviets had annexed, and never imagined that the issue of Poland’s eastern border was anything but a continuing battleground. The more realistic Polish leaders realized that they could scarcely hope to defend their territorial claims on their own. If Poland was to preserve its prewar eastern border, it would need diplomatic support from the other Allies, particularly from England and America.

Yet in the realm of international politics, the Poles were little more than a charity case. They had no real leverage with which to induce anyone to take their part. Under these circumstances, their only diplomatic weapon was whatever goodwill they could induce on the parts of their allies. But their ability to develop public goodwill depended almost entirely on their treatment in the mass media. As the Poles recognized that the Jews played a dominant role in the Anglo-American mass media, as well as in other aspects of the opinion-forming elite, they adopted the tactic of trying to curry Jewish favor.[37]

A second consideration that guided the policy of the Polish government towards the Jews was the role the Jews played in their own internal politics. The power of the London Poles was entirely dependent on the active hostility of the Polish people towards the German authorities. Recognizing that Germany’s anti-Jewish policies in Poland were highly popular with the Polish masses, they saw the need for a policy designed to prevent the Germans from using German-Polish concord on the Jewish question to win the approval, or at least the acceptance, of the Polish masses. Karski himself explained the significance of this situation for the Poles very clearly[38] in a document written in early 1940, which was discovered and published by David Engel.[39] The document lays out in detail the reasons of internal politics that forced Polish leaders into a kind of alliance with the Jews. As Karski wrote:[40]

“The attitude of the Jews toward the Poles and vice versa under German occupation is an extremely important and extremely complicated problem, much more important and much more consequential than under the Bolshevik conquest.

The Germans are attempting at all costs to win over the Polish masses […]

** They are attempting to play upon the growing conflicts between the Polish police or other vestiges of the Polish civil service and the broad masses of society, almost always standing ‘on the side of the people,’ and in the end, ‘the Germans, and the Germans alone, will help the Poles to settle accounts with the Jews.’**

The danger of this situation, as Karski perceived it, was that the handling of the Jewish question provided an issue on which Germans and Poles could heartily agree, paving the way for a broader collaboration that would undermine the power of the government in exile:[41]

“The solution of the ‘Jewish Question’ by the Germans – I must state this with a full sense of responsibility for what I am saying – is a serious and quite dangerous tool in the hands of the Germans, leading toward the ‘moral pacification’ of broad sections of Polish society.

[…] this question is creating something akin to a narrow bridge upon which the Germans and a large portion of Polish society are finding agreement.”

On the basis of this analysis, Karski suggested that it would be desirable to create a “common front” with the Jews and Bolsheviks against the “more powerful and deadly enemy,” the Germans, while “leaving accounts to be settled with the other two later.”[42]

The result of these two considerations was that the Poles were eager to criticize German policy towards the Jews, both in order to persuade their own people to distinguish German “atrocities” from their own intentions towards the Jews, and in order to butter up Anglo-American Jewry in hope of gaining their support on the issue of Poland’s eastern borders. Because of this hope, the Poles were very pliable in their dealings with the Jews as long as their core interests were not affected. Polish appeasement of the Jews was to little avail; their relations are perhaps best summed up in Sikorski’s comment “I am treating the Jews like a soft-boiled egg but to no avail.”[43] Jewish organizations were well aware of the weakness of the Polish position and exploited it, organizing media campaigns against the Poles so as to force them to make more substantial concessions, while offering hopes of support but refraining from definite commitments. These tactics had their intended result of putting the Poles on the defensive. As a British Foreign Office official recognized, the Polish government was “always glad of an opportunity […] to show that they are not anti-Semitic.”[44]

5. The Falsehoods in Karski’s Accounts

The next main goal of this paper is to understand the reason that Karski started out claiming to have gone to Belzec, then claimed to have visited a camp (not Belzec) some distance from Belzec, and then again claimed to have visited Belzec. Before we launch into this question, it’s worth stopping to analyze some simpler features of Karski’s accounts which have caused unnecessary controversy.

False Dates

Raul Hilberg, Michael Tregenza, and Carlo Mattogno have argued against Karski’s visit to Belzec based on the assumption that it took place in October.[45] As we have seen, Karski visited Belzec in September. However, the confusion is understandable, as Karski himself repeatedly gave the former date. Why did he do so?

One possible answer is that it was a simple mistake. This explanation, however, fails to explain the times that Karski claimed to have visited the Warsaw ghetto in January 1943 and left Poland the following month,[46] or claimed to have visited Belzec at the end of 1942 and traveled to London in early 1943.[47] In his meeting with President Roosevelt, Karski even claimed to have left Poland in March 1943.[48] Indeed, there was a broader effort among the Poles to falsify the date of Karski’s departure from Poland, and Karski was not the only one to report this falsely.[49]

Why did Karski give the original false date, of having departed Poland in late October? His biographers suggest that it was to make his information seem more fresh.[50] This was doubtless one reason, but when speaking to a Jewish audience, however, another factor entered the picture, namely the Poles’ desire to gain Jewish support for the Polish position on their eastern border by creating the impression that the Polish government was highly active and concerned on behalf of the Jews. By moving back the date of his departure from Poland, Karski gave the impression that he had hurried to carry the Jews’ news, sometimes even claiming that he had made the trip from Warsaw to London in record time. This story was in keeping with the impression the Poles wanted to make on a Jewish audience, while the reality – that he spent considerable time waiting around in Paris for the right moment to go to London – would not have.

Death Trains

Karski’s most attention-getting claim was that the Jews loaded onto the train at Belzec were killed on the trains with some kind of disinfectant, perhaps quicklime, which had been spread on the floor of the wagons.[51] As we will see below (Section 7), Karski freely admitted in postwar interviews that during the war he believed that Belzec was a transit camp from which Jews were taken for forced labor. He also accepted that the disinfectant was for the purpose of disinfection rather than extermination, thereby admitting that he had not truly believed in the extermination of the Jews by train, which was simply a piece of speculative atrocity propaganda.

6. Karski’s Wartime Accounts of His Trip

Now we turn to our main question: where did Karski say he went? Why are there versions of his story that claim a visit to a “sorting point” fifty kilometers from Belzec?

Examining this question requires that we look at how the trip is described in all major wartime versions of Karski’s story. They are:

- December 5, 1942 Schwarzbart telegram reporting on December 4 meeting with Karski. States that he went to Belzec.[52]

- March 1, 1943 story in The Ghetto Speaks, published by the American Representation of the General Jewish Workers Union of Poland (the Bund),[53] a slightly different version of which appeared in the March 1943 edition of Voice of the Unconquered,[54]the newsletter of the Jewish Labor Committee. Describes visiting a “sorting point” fifty kilometers from Belzec, at which some Jews are killed in “death trains” and others sent on to Belzec, where they are killed with poison gas or electricity.

- May 1943 story, written by Arthur Koestler[55] on the basis of discussions with Karski and later broadcast on the BBC.[56] Stated that Karski visited the camp of Belzec, which was located 15 kilometers south of the town of Belzec.

- Minutes of August 9, 1943 meeting in New York between Karski and Jewish organizations. Says that the camp Karski visited was 12 miles from Belzec, then says it was 12 kilometers from Belzec.[57]

- Story of a Secret State, published November 1944.[58] Reports traveling to Belzec, meeting his contact at a shop, and walking via an indirect route for 20 minutes or 1.5 miles to reach the Belzec camp.[59]

This series of accounts confirms what was noted above, that Karski’s story developed from a trip to Belzec, to a trip to a camp some distance from Belzec, then back again to a trip to Belzec. There are four texts which place Karski at a distance from Belzec: the pair of articles from March 1943, the Koestler broadcast, and the minutes taken by the Representation of Polish Jewry. On closer inspection, however, the March 1943 articles can be split off from the other two, as unlike the latter two, they explicitly distinguish Karski’s destination from Belzec.

The March 1943 Articles

The two March 1943 articles printed in Jewish publications in New York contain both the earliest published version of Karski’s story, and the only version of his story which distinguished the camp he visited from the Belzec camp. They are clearly derived from a common text, but edited differently. These articles were not authored by Karski, although they do derive from his report. Even Karski’s biographers recognize that parts of the story “appear to have been embellished for propaganda purposes or distorted for security reasons”.[60]

The most characteristic feature of these stories is their attempt to distinguish the destination of Karski’s trip from Belzec, and to reconcile the two within a common framework. They state that many of the deported Jews “die before they reach the ‘sorting point’, which is located about 50 kilometers from the city of Belzec”,[61] and claim in Karski’s voice to have visited this location:[62]

“In the uniform of a Polish policeman I visited the sorting camp near Belzec. It is a huge barrack only about half of which is covered with a roof. When I was there about 5,000 men and women were in the camp. However, every few hours new transports of Jews, men and women, young and old, would arrive for the last journey towards death.”

Karski himself never gave this version of the story. Nor did he ever claim to have visited the camp in Polish uniform. As he was acutely aware of the Poles’ need to curry favor with Jewish groups by creating the impression that Polish-Jewish relations were more favorable than they actually were, it is extremely unlikely that Karski would ever have told a story involving a Polish death-camp guard.

The story adds an explicit reconciliation between Karski’s story and the then standard account of Belzec:[63]

“Because there are not enough cars to kill the Jews in this relatively inexpensive manner many of them are taken to nearby Belzec where they are murdered by poison gases or by the application of electric currents. The corpses are burned near Belzec. Thus within an area of fifty kilometers huge stakes are burning Jewish corpses day and night.”

Again, Karski never told this story himself. As Wood and Jankowski correctly deduced, the story, though derived from Karski’s account, has been altered, although they were mistaken about how it was altered. The purpose of the alterations was to reconcile Karski’s experience with the story, then current, of the Belzec electricity/gas extermination camp, as can be seen in the fact that the passages which make this reconciliation do not appear in any other source, and do not match any claim made by Karski himself. The editors, however, slipped up in leaving in a description of the camp as located “on the outskirts of Belzec”. This description is incompatible with the description of the “sorting camp” located 50 kilometers from Belzec. A location 50 kilometers from London might perhaps be described as “on the outskirts of London”, or a location 50 kilometers from New York as “on the outskirts of New York,” but Belzec was only a small town. A location 50 kilometers from Belzec would no more be described as “on the outskirts of Belzec” than Austria would be described as “on the outskirts of Belgium.” The same goes for the text’s reference to the camp as being located “near Belzec”, when Belzec was much too small a place to be the point of reference for a location 50 kilometers away. These passages clearly reflect an earlier version of the text, before it was altered to send Karski to a different location.

While the editing could have been done in New York, it seems more likely that the story had already been altered in London. Thanks to the British censors who intercepted and preserved Schwarzbart’s telegram, we know that Karski came to London claiming to have entered the Belzec camp. Examining the context of his arrival will allow us to see how events likely proceeded. At the time of Karski’s arrival in London in late November of 1942, the campaign which culminated in the Allied declaration of December 17, 1942 was already underway. Ignacy Schwarzbart, the author of the December 1942 telegram which is the first written record of Karski’s visit to Belzec, played a key role in this campaign. Schwarzbart, whom Karski later remembered as “a professional politician and a bit of a manipulator,”[64] was at the time already involved in spreading the story of extermination at Belzec. According to The Black Book of Polish Jewry, on November 15 he had declared:[65]

“An electrocution station is installed at Belzec camp. Transports of settlers arrive at a siding, on the spot where the execution is to take place. The camp is policed by Ukrainians. The victims are ordered to strip naked ostensibly to have a bath and are then led to a barracks with a metal plate for floor. The door is then locked, electric current passes through the victims and their death is almost instantaneous. The bodies are loaded on the wagons and taken to a mass grave some distance from the camp.”

A document containing the same language came to the British Foreign Office on November 26,[66] and the New York Times reported similar[67] remarks concerning electrocution at Belzec made by Schwarzbart on November 25.[68] Other reports circulating at the time, some of which had appeared in the Polish government organ Polish Fortnightly Review just days before Schwarzbart met with Karski,[69] also mentioned Belzec as a place of gassing or electrocution. It cannot have taken Schwarzbart very long to realize that Karski’s story of Jews departing Belzec by train, even if only to be killed on the train, contradicted his story of the Jews arriving at Belzec all being electrocuted or gassed in the camp.

Karski, consequently, was a dangerous witness, whose story did not fit into the account being spread by the Poles and Jews at the time, and which was therefore not particularly wanted. Indeed, Karski’s experience played no role whatsoever in the Polish activities that surrounded the Allied declaration of December 17, 1942, in spite of the fact that he was the only eyewitness to the Reinhardt camps on hand in any Allied country. In fact, the Polish government-in-exile carefully restricted Karski’s contacts in London for months after his arrival,[70] and never arranged to have him inform the British about his experience in Belzec. Meanwhile the Allied declaration went forward with the pointed omission of any mention of the Reinhardt camps, which were relegated to the realms of print and broadcast propaganda, where they were covered without any input from Jan Karski, the only eyewitness on hand.

In short, Karski came to London with an account of his visit to Belzec that contradicted the preexisting propaganda about that camp. He told the Jewish members of the Polish National Council the story of his visit, but they were already engaged in advancing a different story about Belzec, one in which it was an extermination camp that killed with electricity or gas. In spite of the fact that their story was not supported by any eyewitness from within the camp, they continued with their campaign while keeping silent about Karski’s information. They could not but realize the danger inherent in Karski’s account of Belzec, which so dramatically contradicted the stories they were spreading. Naturally, they sought a way to defuse this danger, and came up with the solution of resolving the contradiction between the two stories by placing them at different locations. The articles in The Ghetto Speaks and Voice of the Unconquered are the result. While the alterations to Karski’s story were most likely made within Polish Jewish circles in London,[71] the articles were published not in London but in New York so as to avoid the possibility that Karski would read and contradict them. The expedient worked: as far as I have been able to discover, he remained completely unaware of them.

In light of this background, the odd fact that Schwarzbart’s diary does not mention Karski until March 16, 1943, which caused David Engel to conclude that the two had not previously met, becomes perfectly understandable. Karski’s story was a threat to the propaganda campaign which then occupied Schwarzbart’s attention. Schwarzbart only felt comfortable mentioning Karski in his diary after the American Jewish publications The Ghetto Speaks and Voice of the Unconquered had published the latter’s story in a form that explicitly reconciled it with the official version of Belzec by locating his visit in a “sorting camp near Belzec” rather than in Belzec itself and contrasting the “death train” method that Karski saw with the extermination “by poison gases or by the application of electric currents” that took place in Belzec. By that time, the Allied declaration and the wave of propaganda that surrounded it was a fait accompli, and the danger posed by Karski’s information had been defused.

The Distance Problem

While Karski was unaware of the two articles of March 1943, he was quite familiar with the next source, a story written by the Hungarian Jew Arthur Koestler at the suggestion of SOE chief Lord Selbourne, and on the basis of discussions with Karski himself. The piece clearly stated that Karski visited “the camp of Belzec.”[72] However, it also stated that “[t]he camp of Belzec is situated about 15 kilometers south of the town of that name,”[73] a seriously excessive figure. Karski could not have so described a camp at that location thus, because following the railroad south for 15 kilometers from Belzec would have brought him to Rawa Ruska, a much larger city. Had Karski visited a camp at that location, he would not have described the camp as 15 kilometers south of Belzec, but as on the outskirts of Rawa Ruska.

The same kind of excessive reported distance occurs in the fourth and final “problematic” source, the minutes taken by the Representation of Polish Jewry of an August 9, 1943 meeting between Karski and Jewish organizations, which again did not differentiate the camp Karski visited from Belzec, but placed it first 12 miles and then 12 kilometers from the town.

These sources do not, however, originate directly from Karski, and when he gave his own account of his trip, he said that he walked for 20 minutes from his rendezvous point in the town of Belzec to get to the camp,[74] which is entirely realistic, particularly given that he avoided the main paths. This still leaves the question of why there are second-hand accounts giving an excessive distance. There are several possible explanations. One is that Karski simply did not have a head for distances. He would be far from the only person with this disability. This possibility is supported by the fact that he gave a hugely exaggerated estimate of the camp’s size.[75] On the other hand, he gave a much more realistic (though still overstated) estimate of the distance as 1.5 miles in his account of his Belzec trip,[76] which suggests that the authors of these two texts may have exaggerated for reasons of their own. While Koestler was in direct contact with Karski and consequently could not follow the New York publications in saying that the latter had visited some location other than the Belzec camp, he was still aware of all the different claims being made about extermination methods, and made sure to smooth over the contradictions, saying that the Jews were killed in Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka “by various methods, including gas, burning by steam, mass electrocution, and finally, by the method of the so-called ‘death train’’’,[77] and putting an endorsement of the other accounts into Karski’s mouth:[78]

“I myself, have not witnessed the other methods of mass killing, such as electrocution, steaming, and so on, but I have heard firsthand eye-witness accounts, which describe them as equally horrible.”

Karski did not actually claim to have heard such first-hand accounts, but the remark served to ensure that all the different extermination methods could live happily together. Given Koestler’s concern with ensuring this, it is possible that he altered Karski’s description of the distances to set up the possibility that the conflicting reports about Belzec referred to different locations. The same applies to the Representation of Polish Jewry, which was actively involved in spreading stories of extermination and would have known perfectly well that Karski’s account conflicted with the usual version of Belzec. Of course, this is mere speculation, but it serves to highlight why these second-hand sources do not give any real support to the thesis that Karski visited a location other than Belzec. The decisive factor is that Karski’s first-hand accounts give the location of the camp more accurately.

Another feature to notice is that the texts which place the camp Karski visited somewhere beyond easy walking distance (12 or 15 kilometers, or 12 miles) from the town of Belzec never specify how he got there, or how he returned afterwards. In sharp contrast to this, the wartime texts Karski himself authored, as well as his postwar interviews, are very clear that he met his contact at a shop in the town of Belzec and walked a short distance to the Belzec camp.

Though it is a second-hand source, the Schwarzbart telegram also refutes the reports of excessive distances by placing Karski in Belzec itself. No one who knew the area as Karski did would describe a location 15 kilometers south of Belzec (or 12 miles or kilometers away) as being in the tiny town of Belzec. As this is the earliest source on Karski’s trip, it refutes any notion that he first claimed to have gone to a camp quite some distance from Belzec but subsequently changed his story upon learning the true location of the Belzec camp.

In summary, we have shown that there is no warrant in the wartime sources to support the idea that Karski visited a camp other than Belzec. We have explained the two sources that make this claim as clumsy alterations of Karski’s story meant to harmonize it with the required story of Belzec extermination camp. The two sources that simply place Karski’s destination an excessive distance from the town of Belzec can be explained either in terms of an attempt at reconciling stories or by his poor sense of distances, and are trumped by the more accurate information about Belzec’s location in his first-hand accounts.

7. Belzec in Karski’s Postwar Interviews

Karski’s postwar interviews gave him the chance to tell his story without the need to consider his role in Polish government-in-exile propaganda, and he showed a considerable willingness to correct elements of his story that had been presented falsely in his wartime writings. In describing his trip to Belzec, he admitted that his story of Jews being shot at Belzec was really based on guards shooting in the air to encourage the Jews to board the trains more hastily. He accepted that the disinfectant used in the trains was not aimed at extermination but at disinfection. Most important, he admitted that he had not believed in the stories he spread about Belzec being an extermination camp, but had thought it to be a transit camp.

Karski’s interview with Claude Lanzmann for the movie Shoah is his first and his most detailed. Though Karski discussed Belzec at length, his account so unsettled Lanzmann that it was entirely omitted from Shoah, as well as from the 2010 documentary Le Rapport Karski which was cut from the same footage. The reason for Lanzmann’s discomfort is easy to see. When asked about his knowledge of Belzec at the time of his visit, Karski replied:[79]

“I had heard about Belzec, I knew there was a camp. What I heard, by the way, at that time, even from some Jewish people, was that this was what was called at the time a ‘transitional’ camp.”

Yet reports of Belzec as an extermination camp had circulated widely at that point in time, so this statement implies that members of the Polish underground in Karski’s circle did not believe the reports they were themselves spreading about the extermination of the Jews at Belzec, and that even some Jews had an awareness of Belzec as a transit camp.

When Karski attempted to explain his thoughts on Belzec, Lanzmann sought to change the subject, and even cut Karski off when he tried to return to his point. As Lanzmann attempted to reassert the official history of Belzec, Karski continued to go off script. He insisted that while Belzec might have functioned as a death camp at some other point in time, by the time of his visit it had been turned into a transit camp:[80]

“Lanzmann: And Belzec started to be operational as a death camp in March 1942.

Karski: Yes, only at the moment I visited it, it became apparently truly transitional, which means the Jews were shifted somewhere. The Germans announced that they were going to forced labour, they were going to have good conditions…

Lanzmann: This was to the Jews.

Karski: They said this to the Jews, yes. The Germans always, if they could avoid open trouble, they wanted to avoid it. They wanted everything in as much order, of course, as humanly possible.”

As Karski proceeded to describe his visit, the character of Belzec as transit camp became even clearer:[81]

Karski: […] We entered the camp. As a matter of fact that camp, at the point where I entered it, had no wall. Wire was around it; barbed wire. Whether there were walls in other parts of it, I do not know, I spent in that camp probably no more than 20, 25 minutes – again, I could not take it. The difference between this camp and the Jewish ghetto in Warsaw was that here there was total confusion. The Jews, the population of it, were going somewhere. As I saw it at that time, from the station railroad, as I understood it, there were some rails leading to the camp. Rather primitive built, but I could recognise it, with some sort of a platform. And then the train, which consisted of some 40 cattle trucks. The train facing the camp would move two or three cars, and stop again. From the gate I was standing and observing militiamen, Gestapo Germans – ‘Juden raus! Juden raus!’ – directing them to the tracks.

Lanzmann: You had to cross the camp before arriving at this place…?

Karski: Yes, I saw this from the camp.

Lanzmann: …where you were able to see the loading of the rails.

Karski: Where I was able to see the loading of that primitive rail.

Lanzmann: Yes, but before this you had to cross the camp. Can you describe how you crossed it? What you saw at the time when you crossed it?

Karski: I did not go very deeply into it, because the guide, apparently, and the Estonian wanted to show me this scene. The train was facing that particular gate. We entered the gate, and then we stayed there observing what was happening.

Lanzmann: How long was it between the moment you entered the camp — through another gate – and this point? Was it a big camp?

Karski: I entered through the same gate. I did not wander in the camp. I did not go deeply in the camp. From the Belzec camp, my recollection was the shipment of the Jews from the camp to the trucks in the train. […]

Lanzmann: The people who were loaded into the freight cars – according to you they were working inside the camp since a long time?

… These people, these Jews – were they working inside the camp since a long time? How many days, how many hours?

Karski: I only saw total confusion. They did not look like inhabitants, they looked, as I interpreted it, as some sort of transitional camp. They brought Jews from somewhere, they are taking them somewhere. It did not look to me like an inhabited, regular… – At this point I was standing in the camp, it was total confusion. Shipment of the Jews to the train. What I understood at the time – where are they taking them? They were apparently taking the Jews for forced labour.”

We may note in passing that this description is totally incompatible with the thesis of a visit to Izbica.

Walter Laqueur interviewed Karski in 1979, and included a summary – but not a transcript – of the interview in his book The Terrible Secret.[82]Absent the actual transcript the source is not particularly useful, but broadly speaking Laqueur’s version has Karski confirming what he said in other interviews. In particular, he mentions that “Karski says he learned only in later years that Belzec was not a transit but a death camp and that most of the victims were killed in gas chambers.”[83] In a 1987 interview with Maciej Kozlowski, Karski confirmed this, stating:[84]

“For many years, I could not understand it. I thought Belzec was a transitory camp. It was after the war that I learned that it was a death camp.”

Karski’s attempts to interpret his trip to Belzec

Karski’s interviews consistently contain an attempt to understand the difference between what he saw at Belzec and what, on the received history, he should have seen. This does not appear in his interviews that mentioned his visit to Belzec only briefly or in passing,[85] but featured regularly in his more detailed interviews. The way Karski attempted to reconcile his experiences with received history was by hypothesizing that Belzec had functioned as a death camp, but that by the time of his visit it was in the process of being liquidated and therefore was functioning as a transit camp. This interpretation is already present in his interview with Lanzmann:[87]

“As I understood after the war, at that time they were liquidating the camp as such. By November[86] there was no longer a camp. Whatever the reason, I don’t know, but apparently the last shipment of Jews were taken out of Belzec and either shifted to Sobibor, which had become an extermination camp; or Jews who were taken from the Warsaw or other ghettoes would be for some reason shifted to Belzec for a short time and again go somewhere else.”

Although he admitted that he had been ignorant of exactly which of the Reinhardt camps the Jews from each particular ghetto were sent to, Karski stuck to his guns in the face of Lanzmann’s attempts to refute his story, and reiterated that “at the moment I visited [Belzec], it became apparently truly transitional, which means the Jews were shifted somewhere.”[88] In a June 1981 interview Karski repeated this interpretation, again suggesting that he had witnessed Belzec as a transit camp because it was then being liquidated.[89]

Karski’s interpretation derives from actual accounts of a transport being sent from Belzec to Sobibor during the liquidation of the former camp,[90] which he seized on as a solution to his conundrum of why he saw a transport departing Belzec if it was (as he was told after the war) an extermination camp.

Of course, the idea that Belzec was being liquidated at the time of Karski’s visit is incorrect. He must have been informed of this, since he subsequently stopped interpreting his experience in terms of the liquidation of the camp. While he again interpreted what he had seen at Belzec as a transport of Jews being sent to Sobibor in a 1986 appearance on British television and in a 1987 interview with Maciej Kozlowski, he no longer tried to interpret what he had seen in terms of the liquidation of the camp. Whether from reading or from conversation, he had thought of a new explanation. Picking up on stories which reported that Belzec was an inefficiently run preliminary death camp – a point which Lanzmann had mentioned during their interview[91] – he suggested that the reason he had seen a transport departing Belzec was that Belzec’s poor organization made it unable to absorb all of the transports sent there. As he put it in a 1986 television interview:[92]

“For many years I wondered how it was that I did not see the Jews brought into the camp, but taken out from that camp. Then I discovered, sometimes too many Jews would come to Belzec […]. The commandant, he was apparently negligent […]. and he couldn’t absorb all the Jews sent to the camp; he would send them to Sobibor which was beautifully managed, efficient, and where, of course, the liquidation of the Jews would take place […].”

In his 1987 interview with Kozlowski, he said much the same thing:[93]

“For many years I could not understand it. I thought Belzec was a transitory camp. It was after the war that I learned that it was a death camp. During the trials of the German war criminals in the late 1940s, some Polish railwaymen who cooperated with the underground were cross-examined as witnesses. They explained the scene I saw.

By German standards, Belzec was run very inefficiently. In fact at that time its commander, SS Captain Gottlieb Hering, was on trial before an SS court. The extermination in Belzec was done by exhaust gases from engines salvaged from Soviet tanks. It was a very ineffective way of killing. The engines over-heated, and the whole process of killing lasted for a long time. Sometimes one transport had not been completed by the time a new one arrived. In such cases the new transport was directed to Sobibor, where the death machine was running much better. I witnessed such a scene.”

This interpretation of Karski’s is also untenable: the only attested transport from Belzec to Sobibor dates to the summer of 1943, and at the time of Karski’s visit to Belzec the railway line to Sobibor was closed. Karski’s interpretations are not of interest for reasons of accuracy, but because he made them at all. As he repeatedly stated, he was very puzzled at the fact that his experience at Belzec did not fit with the officially sanctioned version. Faced with this confusion, he groped after whatever explanation he could find.

8. Why Believe That Karski’s Trip Happened at All?

Revisionist writers may find in Karski’s description of Belzec a fairly good picture of what the transit camp should have looked like while in operation. While his wartime accounts were elaborated for the purpose of propaganda, his postwar interviews help to correct this. In short, what he saw was this: there was a great concentration of Jews in Belzec, some of whom were housed in the camp’s barracks but others of whom had to remain in the open. Some of them had died, either on the trains or while waiting in the camp, and the dead bodies had remained there while the Jews themselves did. He saw that the Germans loaded the (surviving) Jews onto a train, and that some forceful measures (shouted commands, shots fired in the air) were needed to accomplish this. He heard that the Jews were being transferred elsewhere for work. All of this is in keeping with the expected functioning of a transit camp. Even Karski’s descriptions of seeing a considerable number of dead bodies in the camp fit with the documented history of Belzec. One of the rare surviving documents on Belzec records the high mortality on a large transport from Kolomea which arrived at Belzec on September 11, 1942 – almost exactly the same time as Karski’s trip.[94] It is even possible that Karski saw this very transport’s departure from Belzec, or if not that then perhaps another transport with similar (if less severe) elevated mortality.

While revisionists should be comfortable accepting Karski’s story, traditionalist Holocaust believers face a different situation. Karski’s account of Belzec is absolutely incompatible with the standard understanding that it was, at the time of Karski’s visit, an extermination camp equipped with homicidal gas chambers, at which transports of Jews arrived but from which they never departed.[95] In light of the total non-viability of the Izbica thesis, it would be no surprise if traditionalist Holocaust historians should decide that Karski’s story was a lie from beginning to end. On the face of things, such an argument might seem acceptable. To be sure, it would be politically awkward, given the degree to which Karski has been promoted as a hero, not to mention his key position in the Polish national mythology concerning Poland’s relation to the Holocaust. When a man has been awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom for having “told the truth, all the way to President Roosevelt himself,”[96] it’s a little awkward to turn around and argue that he was a persistent and determined liar. Nevertheless, the honest Holocaust believer has no choice but to do so.

One reason to be skeptical of this thesis is that as seen above, Karski was demonstrably very puzzled by the discrepancy between what he saw at Belzec and what he was told he should have seen. If his trip did not occur, he would have no reason for such perplexity. It would take a creative liar indeed to repeatedly fabricate such confusion, and to invent multiple explanations for said discrepancy merely so as to lend realism to a story of a trip that never happened.

A second reason telling against the thesis that Karski fabricated the story of his trip lies in the lack of motive. This is not to say that Karski could not have a motive for inventing a story about the extermination of the Jews – on the contrary. Rather, he had no motive for inventing the particular story that he did. As we have seen, Karski’s story arrived in London as a dangerous embarrassment to the Polish-Jewish campaign of atrocity propaganda what was then ramping up, and was totally ignored in the ensuing rush of publicity. If Karski had wished to invent a story of a visit to Belzec death camp, he would not have come up with a story that directly contradicted the propaganda that the Polish government was circulating.

Of course, the uncertainty of human psychology means that the above two considerations cannot be totally conclusive. There is, however, a third and more decisive reason why Karski must have been an actual witness to Belzec. Like all of the Reinhardt camps, Belzec is agreed to have had a structure known as the “tube”, a narrow passageway down which Jews passed. This structure is consistently described throughout Karski’s accounts of his trip to Belzec. The March 1943 articles in The Ghetto Speaks and Voice of the Unconquered describe a “specially constructed narrow passage” down which the Jews were driven as they headed out of the camp and onto the train.[97] The May 1943 account of Karski’s trip written by Arthur Koestler describes “a narrow corridor about two yards in width, formed by a wooden palisade on either side” down which the Jews were forced en route to the departing train.[98] The minutes of an August 1943 meeting with Karski recount that “the Jews were led to a long passageway, built of wood and wire-lathes, and directed them [sic] into waiting freight trains.”[99] The tube is also described in Story of a Secret State,[100] and in a passage quoted above from Karski’s interview with Claude Lanzmann.

Karski must have picked up his knowledge of the tube either from his visit to Belzec, or from some other source. But there are no earlier accounts of any such tube. It is not discussed in the April 1942 AK report on Belzec, nor in the July 10 report of the delegatura on Belzec,[101] nor in Ignacy Schwarzbart’s statement of November 15 or 25, nor in any of the reports on the Reinhardt camps that circulated in London in the run up to the Allied declaration of December 17. As the only eyewitness to Belzec accessible to the Allies, Karski was the first source to report on a tube. His knowledge of the tube cannot have derived from any other report, because there was no other report from which he could have learned of it.

9. Addressing the Arguments against Karski’s Accounts

Karski is almost unique in having been attacked as a witness by both Holocaust revisionists and traditionalists. These critics have seized on inaccuracies in Karski’s statements in order to argue that Karski never visited Belzec. We will now address the arguments in turn.

Karski says that he saw Jews from the Warsaw ghetto in Belzec, but Jews were never deported from Warsaw to Belzec

Both Carlo Mattogno[102] and Raul Hilberg[103] comment on the fact that Karski asserts that the Jews he saw at Belzec were from the Warsaw ghetto,[104] while Jews deported from Warsaw actually went to Treblinka, not Belzec. But Karski never claimed to have talked to the Jews in the camp, or to have received any precise information about their place of origin. His statement that they were from the Warsaw ghetto was simply an understandable, though incorrect, inference on his part. He had been in Warsaw, where he had met with Jewish leaders who told him about the large-scale deportations from the Warsaw ghetto and the transport of the deported Jews to death camps. These Jewish leaders in Warsaw then arranged for him to visit one of these death camps, Belzec. Having received a briefing from Jewish leaders in Warsaw which centered on the liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto, it is entirely unsurprising that when he saw thousands of Jewish deportees in Belzec, whose origin he had no way of determining, he associated them with Warsaw. It is also worth noting that the reports sent by Jewish organizations in Warsaw to the Polish government in exile in London stated that the deportees from Warsaw were sent to Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka.[105] These reports, in particular the reports originating in Warsaw, had a strong tendency to equate the Warsaw ghetto with Polish Jewry as a whole.[106] Karski’s incorrect assumption that the Jews he saw in Belzec were from the Warsaw ghetto is therefore entirely typical of his context.

Karski describes Belzec as being located on a plain, when in fact it is on a hillside

Carlo Mattogno observes that Karski locates Belzec “on a large, flat plain”[107] while it was in fact on a hillside.[108] But the slope of the hillside at Belzec is really quite insignificant.

In her book Hitler’s Death Camps, Konnilyn Feig describes visiting Belzec, and states that the camp “was located on a barren, flat plain.”[109] While this description may be imprecise, it is not grounds for doubting that she visited the camp. Likewise with Karski.

Karski reported entering Belzec disguised as a guard of Baltic nationality, but the non-German guards at Belzec were Ukrainian

Raul Hilberg points out that while Karski claimed to have entered Belzec disguised as a guard of Baltic nationality, most or all of the non-German guards were in fact Ukrainians.[110] Carlo Mattogno makes a similar argument, asserting that Estonian guards never served at Belzec.[111] Here Karski’s descriptions are simply the result of his concern for security, which caused him to modify the details of his experiences in order to protect his contacts and the contacts of his associates. As his biographers explained,

“At various times later in the war, Karski said he had worn Latvian, Lithuanian, and Estonian uniforms. He falsified the nationality for security and perhaps political reasons. ’If I wrote Estonian,’ he explained in an interview, ‘certainly it couldn’t be Estonian. It would be idiotic of me to expose the [underground] Jews’ connections with the guards in that way’.”[112]

Karski’s paranoia over security was so strong that he was even known to alter the nationality he assumed at Belzec from one day to the next.[113]

Karski gave the location of Belzec imprecisely

Carlo Mattogno notes that Karski’s description of the location of Belzec is inaccurate, stating:[114]

“Karski did not even go to the trouble to check the location of Belzec. He places it at a distance some 160 km east of Warsaw, whereas in reality it is nearly 300 km to the south-east of the Polish capital.”

The same error in location was noted by David Silberklang.[115] As mentioned above, Karski was in fact perfectly familiar with the location of Belzec, having seen an earlier camp there in late 1939, as recounted in his 1940 report. There are two possible explanations for the inaccuracy in location. The first is that Karski was again altering the details of his story in the hope of protecting sources, just as he altered the nationality of the guards. This thesis might be opposed on the grounds that such alterations would hardly be an effective measure of protecting sources. But Karski was clearly very into his role as a secret agent, to the point that when detained by the British on his arrival in London he did not even give his real name,[116] and continued to use pseudonyms even when dealing with government officials.[117] Clearly he was the kind of man who might alter details for security’s sake without giving too much thought as to whether the alterations really did increase security.

The second possibility is that Karski simply did not bother to look at a map, or think it worthwhile to give locations precisely. The reports in question were written for a mass audience, which could not be presumed to be interested in the details of Polish geography. When writing for such an audience, why bother with the details of “east” versus “south-east”? As for the inaccurate distance, there is no real reason that Karski would have known the exact distances between even places with which he was familiar. After all, he was not driving between them, and when getting around by train exact distances play a much smaller role. Under these circumstances, whether a writer gets a distance right is more a matter of whether he checked a map than whether he visited a location.

Karski was supposedly gotten into Belzec by bribing one of the guards, but the guards were rich

Carlo Mattogno argues that “the very basis of [Karski’s] story – that the camp guards could be bribed – is in flagrant contradiction to their being described, in the report of July 10, 1942, and others, as having “lots of stolen money and jewelry” and being able to pay 20 gold dollars for a bottle of vodka.”[118] This objection rests on the assumption that the newly wealthy are insusceptible to bribery, which is hardly confirmed by experience. Indeed, one might even argue that increased riches increase the desires of their possessor,[119] and therefore that the newly found riches of the Belzec guards would make them more susceptible to bribery.

Karski could not have entered Belzec because the security was too tight

Raul Hilberg doubts that it would have been possible for Karski to enter Belzec, even in uniform.[120] This claim is contradicted by the results of Michael Tregenza’s research with the villagers in the town of Belzec, which has established that security at Belzec was in fact extremely lax. Contrary to Hilberg’s claim that a uniform and a helper among the Belzec guards would not suffice to get into Belzec, a uniform may not even have been necessary. Belzec’s poor security was known to Jewish leaders, who assured Karski that “chaos, corruption, and panic prevailed” in Belzec, so that getting in would present no difficulty at all.[121]

Karski’s description of the uniform he wore is contrary to the actual uniforms worn by guards at Belzec

While discussing the visit to Belzec, Claude Lanzmann asked Karski what color his uniform was. Karski replied “Yellow. With a kind of parity (? ) boots, black cap I remember.” As it is sometimes claimed that the auxiliary guards at the Reinhardt camps wore all black uniforms, we might appear to have proof that Karski did not visit Belzec. More recent research has contradicted the claim that all guards at the Reinhardt camps wore black uniforms, and revealed that the uniforms worn by the guards at the Reinhardt camps varied considerably.[122] Karski’s description of a “yellow” uniform should be understood as meaning some sort of khaki, or “butternut.” Indeed, Michael Tregenza quotes the notes from a 1981 interview in which Karski described the uniform as consisting of “Khaki tunic, black trousers and boots”.[123] This description does not conflict with what is known about the uniforms worn by the guards at the Reinhardt camps. In fact, former Treblinka prisoners testifying at the trial of Feodor Fedorenko at around the same time as Karski’s interview with Lanzmann recalled the uniforms of the Ukrainian guards as greenish khaki,[124] brown khaki,[125] or some black and some khaki.[126] In view of the considerable variability of accounts of the uniforms of the Ukrainian guards given by individuals who saw these uniforms on a daily basis for months, Karski’s description of the uniform that he wore for less than a day certainly cannot be used to discredit his account.

10. Summary

When he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, Karski was credited with having “told the truth.” This praise was not entirely accurate, as his job as a propagandist active in seeking to win Jewish support for Poland’s cause caused him to embellish his reports with a propagandistic gloss. Yet beneath that finish lay the truth of an actual visit to the Belzec camp.

In his postwar interviews, Karski proved relatively willing to strip the layer of propaganda off the substance of his experiences. He readily conceded that the “death trains” story he had spread was false. He eagerly told everyone who would listen, and some who wouldn’t, that he had seen a transit camp at Belzec. He was puzzled by the contradiction between what he observed at Belzec and what the official history said, and attempted to reconcile the two.

Karski’s report of what he witnessed at Belzec contradicted the Belzec propaganda then circulating, and despite being the only available eyewitness account, his story was ignored in the great surge of publicity about the extermination of the Jews at the Reinhardt camps which began just prior to his arrival in London. His accounts posed such a threat to the officially promoted account of Belzec that they were circulated in a crudely altered form meant to reconcile the two. Holocaust historians threatened by the revelations about Belzec contained in Karski’s interviews then used these altered stories to support the thesis that Karski visited Izbica rather than Belzec, but this thesis is impossible on the basis of both geography and chronology. Thanks to the attentiveness of the British censors, we know that Karski talked about his visit to Belzec immediately upon his arrival in London, and it was not a late addition to his story. Because Karski’s reports contained accurate, previously unknown information about the interior layout of the Belzec camp, his story cannot have been fabricated on the basis of other reports of Belzec.

Jan Karski, therefore, was a genuine witness to the Belzec transit camp.

Notes:

| [1] | Doris Bergen, War and Genocide: a Concise History of the Holocaust. 2nd edition, 2009, p. 204. |

| [2] | Jan Karski, Story of a Secret State. 1944. pp. 339-352. |

| [3] | Here Hilberg is basing his account on the book Defeat in Victory by Jan Ciechanowski, which claims that Karski told President Roosevelt that he had visited Belzec and Treblinka. Karski himself never claimed to have visited the latter camp. |

| [4] | Raul Hilberg, Perpetrators, Victims, Bystanders. p. 223. |

| [5] | E. Thomas Wood and Stanislaw Jankowski. Karski: How One Man Tried to Stop the Holocaust. p. 128. |

| [6] | Bergen, War and Genocide, p. 204; Robert Jan van Pelt, The Case for Auschwitz, p. 144. |

| [7] | Online: http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2012/04/23/president-obama-announces-jan-karski-recipient-presidential-medal-freedo/ |

| [8] | Carlo Mattogno, Belzec, p. 31; Raul Hilberg, Sources of Holocaust Research, pp. 182-3; Hilberg, Perpetrators, Victims, Bystanders, p. 223. |

| [9] | Jan Karski interrogation, PRO WO 208/3692. |

| [10] | Foreign Office minute by F. Roberts, 27 November 1942. PRO FO 371/32231 W16085; Major K.G. Younger to J.G. Ward, 22 December 1942. PRO FO 371/32231 W17455. |

| [11] | Karski, Secret State, p. 354. |

| [12] | Ibid., p. 324. |

| [13] | Wood & Jankowski, Karski, p. 286. |

| [14] | Michael Fleming, Auschwitz, the Allies and Censorship of the Holocaust, Cambridge University Press, 2014, p. 150. |

| [15] | “Eye-Witness Report of the Annihilation of the Jews of Poland,” The Ghetto Speaks, March 1, 1943, p. 1. |

| [16] | Ignacy Schwarzbart to Jewish Congress, 5 December 1942. PRO FO 371/30924 C12313. The telegram gives its recipient as simply “Jewish Congress”, but the address corresponds to the headquarters of the American Jewish Congress. At the time, however, the World Jewish Congress shared office space in New York with the American Jewish Congress, and both organizations were headed by Rabbi Stephen Wise. |

| [17] | Michael Mills has questioned the story of Karski’s visit to the Warsaw ghetto on the basis of a description of the conditions in the Warsaw ghetto prior to the large deportation that appears in The Black Book of Polish Jewry, where it is attributed to Karski’s report. This passage is an expurgated version of one that appeared in The Ghetto Speaks and Voice of the Unconquered in March 1943. There, however, it is not presented as the result of Karski’s experience, but as part of a message he passed on from the Jewish leaders with whom he met. Therefore there is no contradiction between this passage and the date of late August for Karski’s visits to the Warsaw ghetto. |

| [18] | Wood & Jankowski. Karski, p. 128. |

| [19] | e.g. Robert Kuwalek, Belzec, p. 284. Kuwalek, however, confuses the March 1943 sources with the August 1943 account (see Section 6). |

| [20] | Yitzhak Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka. pp. 383, 390. |

| [21] | Online: http://www.bildungswerk-ks.de/izbica/deportationen-von-und-nach-izbica-1 |

| [22] | Alexei Tolstoy, A Polish Underground Worker, and Thomas Mann. Terror in Europe: The Fate of the Jews. National Committee for Rescue from Nazi Terror, 1943, p. 10. |

| [23] | Karski, Secret State, pp. 340-44. |

| [24] | Robert Kuwalek, “Das Durchgangsghetto in Izbica.” Theresienstädter Studien und Dokumente, 2003, pp. 321 – 351, here p. 331. |

| [25] | Thomas Blatt, From the Ashes of Sobibor. Northwestern University Press, 1997, p. 7. |

| [26] | Ibid., p. 228 n. 8. |

| [27] | Kuwalek, “Das Durchgangsghetto in Izbica,” p. 328. |

| [28] | quoted in Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, p. 350. |

| [29] | David Silberklang, “The Allies and the Holocaust: A Reappraisal.” Yad Vashem Studies, vol. 24, 1994, p. 148. |

| [30] | Karski, Secret State, p. 1. |

| [31] | David Engel, An Early Account of Polish Jewry under Nazi and Soviet Occupation Presented to the Polish Government-In-Exile, February 1940. Jewish Social Studies, vol. 45, no. 1, 1983, pp. 1-16, here p. 8. |

| [32] | “Ignacy Schwarzbart to American Jewish Congress,” 5 December 1942. PRO FO 371/30924 C12313. |

| [33] | It would be interesting to know whether the telegram has been retained in the archives of its recipient, the American Jewish Congress. |

| [34] | Only late in the writing of this article did I come across the online paper Poland and Her Jews 1941 – 1944 by Robin O’Neil, which mentions this telegram without giving a citation. |

| [35] | A number of writers have claimed that Karski met with both Zygelbojm and Schwarzbart on December 2nd. This telegram establishes that Karski in fact met with Schwarzbart on December 4th. In fact, in his interview with Claude Lanzmann Karski mentioned that he had been scheduled to meet with both Zygelbojm and Schwarzbart, but that Schwarzbart did not show, and he met with Zygelbojm alone. Apparently, Karski’s meeting with Zygelbojm was on December 2nd, while he subsequently met with Schwarzbart on December 4th. |

| [36] | David Engel, “Jan Karski’s Mission to the West, 1942-1944,” Holocaust and Genocide Studies, vol. 5, no. 4, 1990, pp. 363-380, here p. 365-66. |

| [37] | David Engel, In the Shadow of Auschwitz: The Polish Government-in-Exile and the Jews, 1939-1942. p. 147. |

| [38] | In fact, it was so clear in its portrayal of the lines of agreement between the Germans and the Polish masses that a second version was written, portraying the Polish people as much more favorably inclined towards the Jews. |

| [39] | David Engel, “An Early Account of Polish Jewry under Nazi and Soviet Occupation Presented to the Polish Government-In-Exile,” February 1940. Jewish Social Studies, vol. 45, no. 1, 1983, pp. 1-16. |

| [40] | Ibid., pp. 11-12. |

| [41] | Ibid., pp. 12-13. |

| [42] | Ibid., p. 13. |

| [43] | Engel, In the Shadow of Auschwitz, p. 73. |

| [44] | Frank Roberts minute, 1 December 1942, PRO FO 371/30923 C11923. |

| [45] | Hilberg, Perpetrators, Victims, Bystanders, p. 223; Michael Tregenza, Only the Dead: Christian Wirth and SS-Sonderkommando Belzec; Mattogno, Belzec, p. 31. |

| [46] | Minutes of meeting of Representation of Polish Jewry, August 9, 1943, in Archives of the Holocaust, vol. 8, pp. 287-294, here p. 287. Also reproduced in The Black Book of Polish Jewry, p. 329. |

| [47] | Jan Karski, “Leadership from abroad: Poland and Germany,” in Builders of the World ahead: Report of the New York Herald Tribune Annual Forum on Current Problems. p. 89. |

| [48] | Wood & Jankowski. Karski, p. 296. |

| [49] | Ibid., p. 185. |

| [50] | Ibid., p. 286. |

| [51] | Karski’s accounts consistently include some kind of disinfectant scattered on the floor of the deportation train. It is identified as lime in Voice of the Unconquered and The Ghetto Speaks. By May 1943, in the account of Karski’s experiences authored by Arthur Koestler, the disinfectant had become chlorinated lime (bleaching powder), which supposedly killed the Jews by releasing chlorine gas. In the minutes of an August 9, 1943 meeting with Jewish organizations, it became a mixture of quicklime and chloride, while in Story of a Secret State it became quicklime. In reality, Karski would not have been in a position to identify the disinfectant used, and all of these details are mere narrative decoration. |

| [52] | Ignacy Schwarzbart to American Jewish Congress, 5 December 1942. PRO FO 371/30924 C12313. |

| [53] | “Eye-Witness Report of the Annihilation of the Jews of Poland,” The Ghetto Speaks, March 1, 1943, pp. 1-5. |

| [54] | “Eye-Witness Report of a Secret Courier Fresh from Poland,” Voice of the Unconquered, March 1943, pp. 5, 8. A selection from this article, containing the discussion of Belzec, was reprinted in the 1943 publication The Black Book of Polish Jewry, pp. 135-38. |

| [55] | Maciej Kozlowski, “The Mission That Failed: A Polish Courier Who Tried to Help the Jews,” Dissent, vol. 34, no. 3, 1987, pp. 326-334, here p. 332. Karski adds that the suggestion that Koestler write such a broadcast came from Lord Selbourne, head of the British Special Operations Executive. In other interviews, Karski stated that Lord Selbourne thought his story similar to the untrue stories spread in the first world war of the Germans bashing out the heads of Belgian babies, but supported such propaganda because it was good for public morale. |