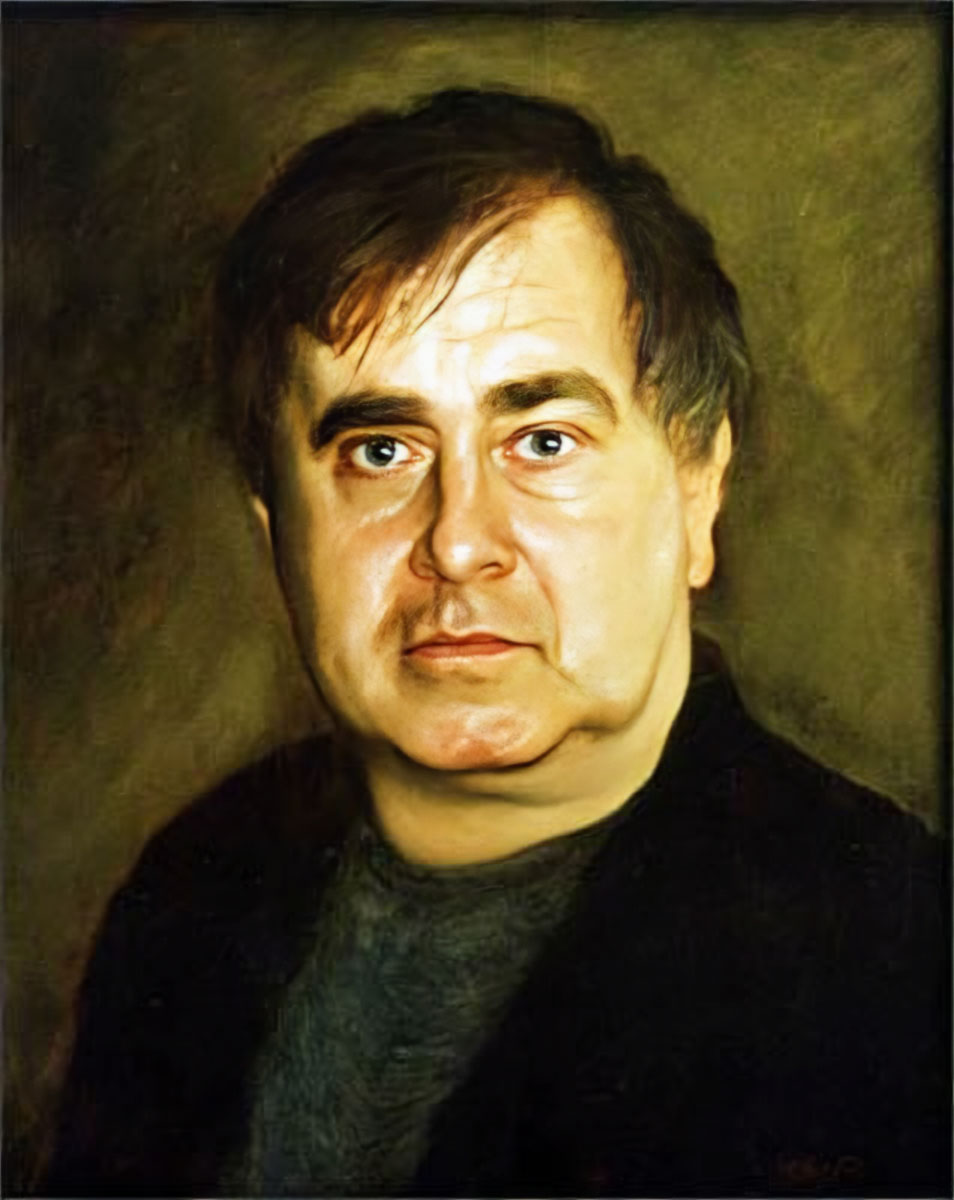

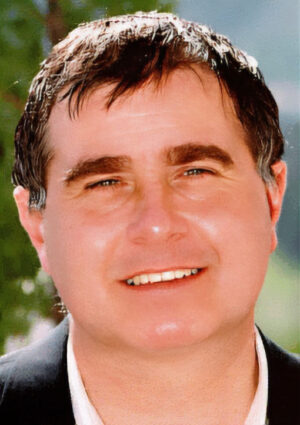

Jürgen Graf, 15 August 1951 – 13 January 2025

Obituary

A great Holocaust Revisionist has passed away. I usually do not write revisionist with a capital letter. But in this case, I have to. Jürgen was a very dear friend of mine. I met him for the first time in 1994 in his hometown Basel, when we went out for dinner one evening. The previous year, Jürgen had published two revisionist books: The 300+-page Der Holocaust-Schwindel (no need to translate that) and the much shorter 100-page booklet Der Holocaust auf dem Prüfstand (The Holocaust on the Test Stand). That same year, the first edition of my expert report on the Chemistry of Auschwitz (today’s English title) as well as the 350-page Vorlesungen über Zeitgeschichte (now in English as Lectures on the Holocaust) had appeared. Evidently, we were both working on our respective projects concurrently, but in complete isolation and ignorance of each other’s existence. We both had been in touch with Dr. Robert Faurisson since 1991, who knew about our work in progress and gave us advice, but Robert never mentioned to either of us anything about the other. That was a pity, because we both could have benefited greatly from each other’s skills and knowledge.

While the books I wrote got me in serious trouble in Germany, ruining my career as a fledgling research Chemist and ending with a prison term for my iconoclastic forensic research, Jürgen initially only lost his position as a foreign-language teacher in Switzerland, while a latter book he wrote got him a prison term as well (which he successfully dodged serving by going into Russian exile).

During our dinner that memorable evening in 1994, we decided to work no longer separately, but to join forces in order to help each other in our efforts to understand what really happened to the Jews within the German sphere of influence during the Second World War.

While I went into English exile in 1996 and established a small German-language revisionist outlet there (in 1998 christened Castle Hill Publishers), Jürgen teamed up with Italian revisionist researcher Carlo Mattogno and went on several trips to archives in the former Eastern Bloc. Jürgen was a multi-linguist who could converse in 12 languages, I think. Or was it 17? I forgot. Either way, it is well beyond most people’s comprehension how a human brain can competently juggle so many different languages. And he was not just limited to the usual European ones (German, French, English, Russian, Polish, Danish, Spanish, Italian…). No, he spoke Indonesian and Mandarin Chinese as well. He once told me jokingly that he developed serious feelings of inferiority when meeting a Russian who spoke 21 languages fluently.

His language skills came in handy when he and Carlo visited Polish and Russian archives during the 1990s. Without Jürgen’s language skills and his winning charm, Carlo could not have traveled to these countries and receive access to so much archival material. One fateful visit of the two concerned an archive in Moscow that stored the documents left behind at Auschwitz by the Central Construction Office of the Waffen SS and Police Auschwitz, the organization in charge of building the camp – fences, housings, watch towers, toilets, showers, disinfestation buildings, you name it… and the infamous crematoria said to have housed the alleged homicidal gas chambers. It was not so much the contents of this archive that was fateful for Jürgen, though. It was the lady who was in charge of that collection. She had been sifting through those roughly 80,000 documents for years, categorizing and cataloguing them. When Jürgen and Carlo entered the archive, this lady was very accommodating and also very honest. She told the two revisionist researchers straight away that, in her humble opinion, there isn’t a trace of evidence in that collection that homicidal gas chambers existed at Auschwitz, and that she therefore does not believe in the horror tales about Auschwitz. Olga was her name, and she ended up marrying Jürgen. They were together until death parted them.

Olga was a typical Russian otherwise (or rather a Belorussian, if I am not mistaken, originally from Minsk). She did not believe in the gas-chamber myth, but she believed that all Americans are evil. Some Soviet propaganda had to stick. Anyway, Jürgen and Olga came to visit me in the summer of 2002 when I lived at Coosa Circle in Huntsville, Alabama. My rented house was at the northern outskirts of the town, bordering at a forest with a fine network of hiking paths, which is rare in America. The Graf’s stayed with me for two weeks, if I remember correctly. We went on numerous hiking trips through the woods, where I refreshed Jürgen’s rusty memory of German Wanderlieder (hiking songs). We had a blast together. We sang some folk songs when back home as well, some of which with a clear Eastern-European influence, which Olga loved. Though she did not understand the German lyrics, she heard the sounds of Russia in the melodies. It was the last time I saw Jürgen in person. When they left, Olga had radically revised her opinion about Americans: wherever she went and revealed her (Belo)Russian background, she was warmly welcome and embraced by all the Americans she met. There was no hostility in any of them.

My relationship with Jürgen over the subsequent years was mostly limited to him translating books into German that were written mainly or exclusively by our pal Carlo Mattogno. Jürgen was an excellent, if not even an extraordinary translator. He would improve any book he received for translation not only by making an accurate translation, but by polishing up the language and making it sound more elegant and pleasant to read. He also sometimes took the liberty of emphasizing a point an author was making by adding irony, sarcasm and an occasional snide remark. Needless to say, that did not always find the author’s approval. But considering the at times absurd or even grotesque material he had to wade through, Jürgen couldn’t help himself but let his humor and wit shine through. I had to clean up after him a few times to keep the material free of additions not intended by the author. But I must admit that I personally liked it. Carlo is a hyper-dry author, and Jürgen threw some spices into the mix that seasoned revisionist readers might like. Only, the choir boys are not our only target audience. Serious scholars are also important, and they usually scoff at such rhetorical devices.

Jürgen’s post-teacher career consisted mainly of doing professional translations from various languages into his native German, most often for right-wing publishing companies in Germany. By 2016, Jürgen’s workload had become so intense, and his financial situation so uncertain, that he had to turn me down when I asked him for his usually steeply discounted service of translating one more of Carlo’s books. Hence, I had to sit down and do it myself. After a few years and several of Carlo’s books, and with the indispensable assistance of machine translations, I had become rather skilled in translating Italian texts, or rather editing machine-translated texts. I no longer needed any real-person translator. That was good for revisionism, as it removed the main bottleneck to get new research published, but it also loosened the close ties I used to have with Jürgen. We started losing sight of each other.

Jürgen scoffed at the idea of using computers to translate texts. When it comes to lingual elegance, he was right. His translation skills always surpassed that of Artificial Dumbness. But mine do not, and so I use machine translations as a springboard to get a head start, and it’s been working for me just fine. The problem is that translating a 300-page book by a professional translator costs at least some $3000, which we revisionists cannot afford. Moreover, a professional translator commonly submits a text that is a formatting mess, requiring days of editing and formatting. Today’s translation software, on the other hand, leaves the formatting perfectly intact, and costs me only a few dollars. While that text needs thorough proofing and editing to catch the occasional glitch, that is not much more effort than proofing/editing a real-person translator’s idiosyncrasies and occasional mess-ups. Make no mistake: the days of professional translators and interpreters are counted. Soon, no one will need to speak different languages anymore. It will be a poorer world.

Jürgen is spared from having to experience this. When I heard the sad news last summer that he was struggling once more with cancer, this time more seriously so, I knew that a final farewell was probably approaching. I am glad to know that he received the support he thought he needed for this final battle.

I am sad to have lost yet another dear friend and comrade in this epic battle for truth in history. Just two days earlier, I had lost another friend who was very dear to me. Born in the same year as Jürgen, she died in my arms. I was devastated by this experience. Now I hear that Jürgen followed her into the eternal hunting grounds. My heart bleeds.

May their souls rest in peace, and their spirits guard us!

Bibliography

Below is a list of Jürgen’s books. I list English editions, where available, and link to their online location. The year(s) in parentheses denote(s) the first (English) and the current edition for each book. Feel free to browser them at your leisure:

- Der Holocaust auf dem Prüfstand (1993)

- Der Holocaust-Schwindel (1993)

- Todesursache Zeitgeschichtsforschung (1996)

- Das Rotbuch. Vom Untergang der Schweizerischen Freiheit (1997)

- The Giant with Feet of Clay (2001, 2022)

- Concentration Camp Majdanek (with C. Mattogno, 2003, 2016).

- Concentration Camp Stutthof (with C. Mattogno, 2003, 2016).

- Treblinka: Extermination Camp or Transit Camp? (with C. Mattogno, 2004, 2020)

- Sobibór: Holocaust Propaganda and Reality (with T. Kues, C. Mattogno, 2010, 2018)

- The “Extermination Camps” of “Aktion Reinhardt” (with T. Kues, C. Mattogno, 2013, 2015).

- White World Awake! (2016)

- Auschwitz: Eyewitness Reports and Perpetrator Confessions of the Holocaust (2019)

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 2025, Vol. 17, No. 1

Other contributors to this document:

Editor’s comments: