Mahatma Gandhi’s Persecution

On the Triviality of Mahatma Gandhi’s Struggle for Civil Rights in South Africa

Introduction

When I was languishing in a German prison for my historical research between 2005 and 2009, I had the opportunity to read many works of classic literature. Among them was also a book on Mahatma Gandhi’s basic works. It explained his principles during his struggle for civil rights and the right to self-determination in South Africa and India.[1] In my defense speech during my trial in late 2006 and early 2077, I used several quotations from the works of Gandhi which seemed to me crucial also for the struggle for civil rights that we revisionists find ourselves in. They can all be found on page 184 of my book Resistance is Obligatory:[2]

“So long as the superstition that men should obey unjust laws exists, so long will their slavery exist.”[3]

“Democracy is not a state in which people act like sheep. Under democracy individual liberty of opinion and action is jealously guarded.”[4]

“In other words, the true democrat is he who with purely non-violent means defends his liberty and therefore his country’s and ultimately that of the whole of mankind.”[5]

“I wish I could persuade everybody that civil disobedience is the inherent right of a citizen. He dare not give it up without ceasing to be a man. […] But to put down civil disobedience is to attempt to imprison conscience. […] Civil disobedience, therefore, becomes a sacred duty when the State has become lawless, or which is the same thing, corrupt. […] It is a birthright that cannot be surrendered without surrender of one’s self-respect.”[6]

“I am convinced more than ever that an individual or a nation has the right, even the duty to resort to [civil disobedience], if its existence is at stake.”[7]

Mahatma Gandhi is a giant among the idols of peaceful resistance and civil disobedience against abusive authorities. Back in 2007, I was quoting him with reverence, awe and admiration.

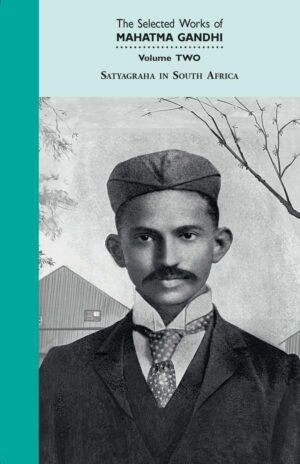

This past Christmas, a supporter of mine of Indian extraction, after having read my book Resistance is Obligatory, had the generosity of sending me as a gift the book that is the focus of this review. The writings by and about Gandhi that I read while in prison were laying out the principles of Gandhi’s activism throughout the decades.[8] They did not contain a detailed description of these struggles. I only remember a brief summary of what he went through during his early years while lobbying for equal rights for Indian immigrants in South Africa.

The book reviewed here is a rather detailed and riveting history of Gandhi’s action and experiences in South Africa.

Stopping and Reversing Mass Immigration

The European Rulers of South Africa needed cheap labor to till their farms and slog in their gold and diamond mines. Slavery had been abolished by the British empire, and the native population was not inclined to leave their stone-age subsistence behind in order to toil in the fields and mines of the White Man under rather terrible conditions. Therefore, the British resorted to incentivizing impoverished Indians to immigrate to South Africa in order to do these menial labors – as indentured workers. However, the European rulers were not inclined to give these Indian immigrants equal rights, even after their term of indenture had ended after 5 years. In fact, toward the turn of the 19th to the 20th century, attitudes reversed: European fears of getting eventually outnumbered and replaced by Indians led to the introduction of laws that limited immigration to people fluent in a European language. Other laws aimed at making the lives of Indians already present in South Africa so miserable that they would go back to India voluntarily.

Gandhi’s fight against these laws in certain ways resembles the struggle of civil-rights groups today in Europe and the U.S. lobbying for granting equal rights, including citizenship, to all immigrants, and to lobby for a more liberal immigration policy. While Gandhi did not oppose restrictions on immigration as such – he understood and respected the Europeans’ fear of getting outnumbered – he intentionally violated laws that prohibited the entry of non-registered Indians into certain South African provinces (which had varying laws in this regard).

During those years, the South-African authorities introduced obligatory ID cards for immigrants with either photos or fingerprints as unique identifiers, in order to be able to distinguish new unregistered (hence illegal) immigrants from those who had settled in South Africa before the introduction of laws restricting immigration. These ID cards were a major bone of contention for Gandhi and his supporters. What we all take for granted today – government-issued photo IDs with biometric data – was an outrage back then, enough to stage a revolt.

Persecution – a Comparison

Gandhi got imprisoned three times throughout his stay in South Africa. Initially, the maximum penalty for the offenses involved was three months’ imprisonment. Gandhi first got a two-months term, and later another three-months term, both of which he had to serve in full. Later, he was sentenced to nine plus three months, hence a year in total, among others for stirring up the people to violating South Africa’s immigration laws. However, due to mass protests and strikes, he was released after only six weeks, and then reached an agreement with the South African government that was a resounding victory for his movement. This ended Gandhi’s persecution in South Africa.

To a current-day revisionist of European extraction, this sounds like paradise. The lowest maximum term for violating “denial” laws is Luxemburg’s six-months term, while the highest maximum term exists in Austria with 20 years (if committed together with National-Socialist revivalism). I spent a total of 45 months in German prisons for two separate offenses (14 plus 30 months, plus one month in U.S. deportation confinement). No revisionist ever gets released early, and if anyone should dare to organize protests and strikes against such incarceration, they might face getting arrested as well.

Throughout Gandhi’s entire struggle in South Africa, the newspaper he had founded to report about the ongoing struggle for civil rights, titled Indian Opinion, appeared unimpeded – except for occasional staffing shortages and financial constraints. The South-African authorities never interfered with it in any way. No confiscations of issues, raids of the editorial offices, confiscations of printing machinery, arrest of editors, authors, printers, distributors or publishers were ever reported.

Confiscations of revisionist periodicals and books are the norm in continental Europe. Periodicals such as Inconvenient History could not exist for long before having their offices raided by the police, all issues confiscated and burned under police supervision, all means to produce new copies and issues destroyed (printers, computers, data carriers etc.), and anyone involved prosecuted: publishers, editors, authors, printers, distributors, importers, exporters, warehousing managers, sellers, and buyers of multiple copies.

The associations created by Gandhi and his supporters to organize their struggle against the South-African authorities, including major real estates to gather his followers, equally never experienced any harassment or impediment from anyone.

On the 9th of November 2003, several revisionists established in Germany the “Association for the Rehabilitation of those Persecuted for Contesting the Holocaust.”[9] Its purpose was “to eliminate the previously prevailing isolation of those persecuted through organized efforts, to ensure that their fight for justice receives the necessary public attention, and to provide the financial means for a successful legal battle”. Hence, it is a perfect equivalent of Gandhi’s organization he named “Satyagraha.” The aim of this German group was to “reopen criminal proceedings that led to convictions for denying or trivializing the Holocaust in accordance with Section 130 (3 and 4) of the German Criminal Code.”[10]

The founding members were, among others: Robert Faurisson, Jürgen Graf, Ursula Haverbeck-Wetzel, Gerd Honsik, Horst Mahler, Germar Rudolf, Bernhard Schaub, Hans Schmidt, Wilhelm Stäglich, Fredrick Töben, Ernst Zündel, Ingrid Zündel-Rimland, Anneliese Remer (widow of Otto Ernst Remer)

On May 7, 2008 (mind the timing with Germany’s “liberation day” on May 8), the German Minister for the Interior Wolfgang Schäuble declared this civil-rights organization anti-constitutional and banned it.[11] At that point, several of this group’s leading members had been arrested and sentenced to long prison terms (Horst Mahler, Ernst Zündel and myself). Anyone who would henceforth try to maintain this organization or establish any similar successor civil-rights organization would be in violation of criminal law. Hence, if the Committee for Open Debate On the Holocaust were an organization in a long list of European countries outlawing opposition to anti-revisionist censorship laws, it would have been banned and dissolved a long time ago, and any recalcitrant members and volunteers would have been arrested, prosecuted, sentenced and locked away for years.

Gandhi mentions repeatedly that they had trouble organizing their struggle due to a lack of funds. That’s all the financial constraints he experienced. Until 2004, I used to operate, usually through friends or relatives, a bank account for normal business operations in Germany. However, in the summer of 2004, my German bank account got “arrested” by the German government, and all assets in it confiscated. A good friend of mine who had managed that German bank account for me was arrested, and his house worth roughly a quarter-million dollars was confiscated as “collateral” for an expected fine in that order of magnitude, which was expected in some future court case against me for selling “contraband literature.” (My friend and his house were eventually released.) Banks in Europe close accounts of revisionist individuals and enterprises with some regularity, even in countries where contesting the orthodox Holocaust narrative is as such is not a crime (HSBC and Barclays in the UK, for instance). Online payment gateways such as PayPal, Authorize.net, Wise and Square refuse to do business with revisionists, and a long string of payment processors have closed accounts and banned us over the decades. Furthermore, American Express has banned the use of their cards on revisionist websites.

In other words: Gandhi never really faced persecution worthy of that name. The British and South Africans pretty much let him have his way. In fact, he had many fans and supporters among them. I wonder what he and his movement would have looked like, had the South-African and British authorities and societies applied the same persecution methods as modern-day authorities and societies do against us revisionists.

Hidden Racism

Gandhi’s early writings (1903 to 1907) have a number of remarks about South Africa’s native population which are clearly racist in nature. While Gandhi was fighting against European racism toward Indians during those early years, he evidently had no qualms displaying the same kind of racism against people he considered to be inferior to his own kind.[12] However, his later-day account of his South African struggle reads quite differently. In an early chapter titled “History” (pp. 7-18), he describes the native population of South Africa and their customs in some detail, yet without using any derogatory terms. Quite to the contrary, some of the terms he uses are quite favorable. It thus seems that Gandhi, in his later years, has corrected his initial prejudices.

Conclusion

There are numerous reasons why persecution against revisionists in our days is so much more severe than what Gandhi ever experienced. The most important of them is that the field in which he struggled with his civil disobedience neither attacked taboo topics nor a major, if not the most important, psychological mainstay of the world order of his time. Battles against discrimination based on race and ethnicity (the Indians in South Africa), as well as the fight for national de-colonization and self-determination of third-world countries (India) were and still are topics that find support and majorities everywhere. We revisionists simply picked the most-difficult topic to be granted equal civil rights. We’ve got public opinion firmly stacked against us. All the more important it is to follow what Gandhi called “Satyagraha”: peaceful and conciliatory disobedience and resistance against unjust laws, and the strict acknowledgment that it is unacceptable to argue for, advocate, justify, promote or condone the violation of anyone’s civil rights and rights to self-determination, be it in the past, present or future.

Endnotes

| [1] | Mahatma K. Gandhi, The Selected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Vol. 4: The Basic Works, Navajivan Publishing House, Ahmedabad, 1969. |

| [2] | 2nd ed., Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield, 2016; https://armreg.co.uk/product/resistance-is-obligatory-address-why-freedom-speech-matters/. |

| [3] | Shriman Narayan (ed.), The Selected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, vol. 4, Navajivan Publishing House, Ahmedabad 1969, p. 174. |

| [4] | Young India, 2 March 1922; Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India (ed.), The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi (Electronic Book), Publications Division Government of India, New Delhi 1999, 98 volumes (https://www.gandhiservefoundation.org/about-mahatma-gandhi/collected-works-of-mahatma-gandhi/), subsequently CWMG, here vol. 26, p. 246. |

| [5] | Harijan, 15 April 1939, CWMG, vol. 75, p. 249. |

| [6] | Young India, 5 Jan. 1922; CWMG, vol. 25, pp. 391f. |

| [7] | Young India, 14 Feb. 1922. |

| [8] | Among them also the secondary works by Fritz Kraus (ed.), Vom Geist des Mahatma, Holle, Baden-Baden 1957; and Michael Blume, Satyagraha. Wahrheit und Gewaltfreiheit, Yoga und Widerstand bei Gandhi, Dissertation, Hinder + Deelmann, Gladenbach 1987. |

| [9] | Horst Mahler, “Verein zur Rehabilitierung der wegen Bestreitens des Holocausts Verfolgten,” Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung 7(3&4) (2003), p. 448. |

| [10] | See https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Verein_zur_Rehabilitierung_der_wegen_Bestreitens_des_Holocaust_Verfolgten. |

| [11] | Press release by the German Ministry for the Interior dated 7 May 2008; https://tinyurl.com/245zmj46. |

| [12] | See Arthur Kemp, “The Racism of the Early Mahatma Gandhi,” The Revisionist 2(2) (2004), pp. 184-186; https://codoh.com/library/document/the-racism-of-the-early-mahatma-gandhi/. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 2024, Vol. 16, No. 2

Other contributors to this document:

Editor’s comments: