Neutral Sources Document Why Germany Invaded Poland

Most historians state that Germany’s invasion of Poland was an unprovoked act of aggression designed to create Lebensraum and eventually take control of Europe. According to conventional historians, Adolf Hitler hated the Polish people and wanted to destroy them as his first step on the road to world conquest.[1]

British historian Andrew Roberts, for example, writes:[2]

“The Polish Corridor, which had been intended by the framers of the Versailles Treaty of 1919 to cut off East Prussia from the rest of Germany, had long been presented as a casus belli by the Nazis, as had the ethnically German Baltic port of Danzig, but, as Hitler had told a conference of generals in May 1939, ‘Danzig is not the real issue. The real point is for us to open up our Lebensraum to the east and ensure our supplies of foodstuffs.”’

British historian Richard J. Evans writes:[3]

“In 1934, when Hitler had concluded a 10-year non-aggression pact with the Poles, it had seemed possible that Poland might become a satellite state in a future European order dominated by Germany. But, by 1939, it had become a serious obstacle to the eastward expansion of the Third Reich. It therefore had to be wiped from the map, and ruthlessly exploited to finance preparations for the coming war in the west.”

This article uses non-German sources to document that, contrary to what most historians claim, Germany’s invasion of Poland was provoked by the Polish government’s acts of violence against its ethnic German minority.

Historical Background

Polish Foreign Minister Józef Beck accepted an offer from Great Britain on March 30, 1939, that gave an unconditional unilateral guarantee of Poland’s independence. The British Empire agreed to go to war as an ally of Poland if the Poles decided that war was necessary. In words drafted by British Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax, Neville Chamberlain spoke in the House of Commons on March 31, 1939, declaring:[4]

“I now have to inform the House… that, in the event of any action which clearly threatened Polish independence and which the Polish government accordingly considered it vital to resist with their national forces, His Majesty’s Government would feel themselves bound at once to lend the Polish government all support in their power. They have given the Polish government an assurance to that effect.”

Great Britain’s unprecedented “blank check” to Poland led to increasing violence against the German minority in Poland. The book Polish Acts of Atrocity against the German Minority in Poland answers the question why the Polish government allowed such atrocities to happen:[5]

“The guarantee of assistance given Poland by the British government was the agent which lent impetus to Britain’s policy of encirclement. It was designed to exploit the problem of Danzig and the Corridor to begin a war, desired and long-prepared by England, for the annihilation of Greater Germany. In Warsaw, moderation was no longer considered necessary, and the opinion held was that matters could be safely brought to a head. England was backing this diabolical game, having guaranteed the ‘integrity’ of the Polish state. The British assurance of assistance meant that Poland was to be the battering ram of Germany’s enemies. Henceforth, Poland neglected no form of provocation of Germany and, in its blindness, dreamt of ‘victorious battle at Berlin’s gates.’ Had it not been for the encouragement of the English war clique, which was stiffening Poland’s attitude toward the Reich and whose promises led Warsaw to feel safe, the Polish government would hardly have let matters develop to the point where Polish soldiers and civilians would eventually interpret the slogan to extirpate all German influence as an incitement to the murder and bestial mutilation of human beings.”

Most of the outside world dismissed this book as nothing more than Nazi propaganda used to justify Hitler’s invasion of Poland. However, as we will see in this article, the violence against Poland’s ethnic Germans that led to Hitler’s invasion of Poland has been well-documented by numerous non-German sources.

American Sources

American historian David Hoggan wrote that German-Polish relationships became strained by the increasing harshness with which the Polish authorities handled its German minority. More than 1 million ethnic Germans resided in Poland, and these Germans were the principal victims of the German-Polish crisis in the coming weeks. The Germans in Poland were subjected to increasing doses of violence from the dominant Poles. Ultimately, many thousands of Germans in Poland paid for this crisis with their lives. They were among the first victims of Britain’s war policy against Germany.[6]

On August 14, 1939, the Polish authorities in East Upper Silesia launched a campaign of mass arrests against the German minority. The Poles then proceeded to close and confiscate the remaining German businesses, clubs and welfare installations. The arrested Germans were forced to march toward the interior of Poland in prisoner columns. The various German groups in Poland were frantic by this time, and they feared that the Poles would attempt the total extermination of the German minority in the event of war. Thousands of Germans were seeking to escape arrest by crossing the border into Germany. Some of the worst recent Polish atrocities included the mutilation of several Germans. The Poles were warned not to regard their German minority as helpless hostages who could be butchered with impunity.[7]

William Lindsay White, an American journalist, recalled that there was no doubt among well-informed people that, by August 1939, horrible atrocities were being inflicted every day on the ethnic German minority of Poland. White said that a letter from the Polish government claiming that no persecution of the Germans in Poland was taking place had about as much validity as the civil liberties guaranteed by the 1936 constitution of the Soviet Union.[8]

Donald Day, a well-known Chicago Tribune correspondent, reported on the atrocious treatment the Poles had meted out to the ethnic Germans in Poland:[9]

“I traveled up to the Polish Corridor where the German authorities permitted me to interview the German refugees from many Polish cities and towns. The story was the same. Mass arrests and long marches along roads toward the interior of Poland. The railroads were crowded with troop movements. Those who fell by the wayside were shot. The Polish authorities seemed to have gone mad. I have been questioning people all my life, and I think I know how to make deductions from the exaggerated stories told by people who have passed through harrowing personal experiences. But even with generous allowance, the situation was plenty bad. To me the war seemed only a question of hours.”

Hoggan wrote that the leaders of the German minority in Poland repeatedly appealed to the Polish government for mercy during this period, but to no avail. More than 80,000 German refugees had been forced to leave Poland by August 20, 1939, and virtually all other ethnic Germans in Poland were clamoring to leave to escape Polish atrocities.[10]

British Ambassador Nevile Henderson in Berlin was concentrating on obtaining recognition from Halifax of the cruel fate of the German minority in Poland. Henderson emphatically warned Halifax on August 24, 1939, that German complaints about the treatment of the German minority in Poland were fully supported by the facts. Henderson knew that the Germans were prepared to negotiate, and he stated to Halifax that war between Poland and Germany was inevitable unless negotiations were resumed between the two countries. Henderson pleaded with Halifax that it would be contrary to Polish interests to attempt a full military occupation of Danzig, and he added a scathingly effective denunciation of Polish policy. What Henderson failed to realize is that Halifax was pursuing war for its own sake as an instrument of policy. Halifax desired the complete destruction of Germany.[11]

On August 25, 1939, Ambassador Henderson reported to Halifax the latest Polish atrocity at Bielitz, Upper Silesia. Henderson never relied on official German statements concerning these incidents, but instead based his reports on information he had received from neutral sources. The Poles continued to forcibly deport the Germans of that area, and compelled them to march into the interior of Poland. Eight Germans were murdered and many more were injured during one of these actions. Henderson deplored the failure of the British government to exercise restraint over the Polish authorities.[12]

Hoggan wrote that Hitler was faced with a terrible dilemma. If Hitler did nothing, the Germans of Poland and Danzig would be abandoned to the cruelty and violence of a hostile Poland. If Hitler took effective action against the Poles, the British and French might declare war against Germany. Henderson feared that the Bielitz atrocity would be the final straw to prompt Hitler to invade Poland. Henderson, who strongly desired peace with Germany, deplored the failure of the British government to exercise restraint over the Polish authorities.[13]

Hitler invaded Poland to end the atrocities against the German minority in Poland. American historian Harry Elmer Barnes agreed with Hoggan’s analysis. Barnes wrote:[14]

“The primary responsibility for the outbreak of the German-Polish War was that of Poland and Britain, while for the transformation of the German-Polish conflict into a European War, Britain, guided by Halifax, was almost exclusively responsible.”

Barnes further stated:[15]

“It has now been irrefutably established on a documentary basis that Hitler was no more responsible for war in 1939 than the Kaiser was in 1914, if indeed as responsible…Hitler’s responsibility in 1939 was far less than that of Beck in Poland, Halifax in England, or even Daladier in France.”

Other Sources

Dutch historian Louis de Jong wrote that on March 25, 1939, windows were smashed in the houses of many ethnic Germans in Posen and Kraków, and in those of the German embassy in Warsaw. German agricultural co-operatives in Poland were later dissolved and many German schools were closed down, while ethnic Germans who were active in the cultural sphere were taken into custody. Around the middle of May 1939, in one small town where 3,000 ethnic Germans lived, many household effects in houses and shops were smashed to bits. The remaining German clubs were closed in the middle of June.[16]

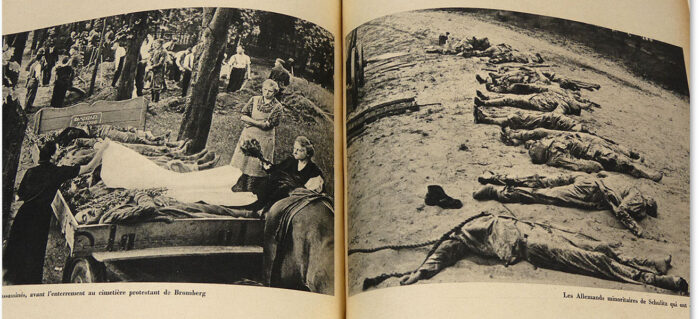

De Jong wrote that, by mid-August 1939, the Poles proceeded to arrest hundreds of ethnic Germans. German printing shops and trade union offices were closed, and numerous house-to-house searches took place. Eight ethnic Germans who had been arrested in Upper Silesia were shot to death on August 24 during their transport to an internment camp.[17]

On August 7, 1939, the Polish censors permitted the newspaper Illustrowany Kuryer Codzienny in Kraków to feature an article of unprecedented recklessness. The article stated that Polish units were constantly crossing the German frontier to destroy German military installations, and to carry confiscated German military equipment into Poland. The Polish government allowed this newspaper, with one of the largest circulations in Poland, to tell the world that Poland was instigating a series of violations of her frontier with Germany.[18] The Polish newspaper Kurier Polski also declared in banner headlines that “Germany Must Be Destroyed!”, while negotiations with Hitler were still in progress during August 1939.[19]

Polish Ambassador to America Jerzy Potocki unsuccessfully attempted to persuade Polish Foreign Minister Józef Beck to seek an agreement with Germany. Potocki later succinctly explained the situation in Poland by stating “Poland prefers Danzig to peace.”[20] Polish armed forces Commander-in-Chief Edward Rydz-Smigly also declared that Poland was prepared to fight even without allies if Germany touched Danzig. Rydz-Smigly declared that every Polish man and woman of whatever age would be a soldier in the event of war.[21]

British Royal Navy Capt. Russell Grenfell was highly critical of Britain’s unilateral unconditional guarantee of Poland’s independence. He said that, in general, special territorial guarantees were a means by which a great Power could turn its challengers into world criminals. Grenfell wrote:[22]

“This would have worked out very awkwardly for Britain in the days when she was the challenging power; as, for example, against Spain in the 16th century, Holland in the 17th, and Spain and France in the 18th.”

Grenfell was also critical of Britain’s guarantee of Poland’s independence because a guarantee is itself a challenge. He wrote that a guarantee “publicly dares a rival to ignore the guarantee and take the consequences; after which it is hardly possible for that rival to endeavor to seek a peaceful solution of its dispute with the guaranteed country without appearing to be submitting to blackmail.” Grenfell said that a guarantee may therefore act as an incitement to the very major conflict which it is presumably meant to prevent.[23] This is exactly what happened in the case of Britain’s guarantee of Poland’s independence.

Aftermath of Invasion

The Germans in Poland continued to experience an atmosphere of terror in the early part of September 1939. Throughout the country the Germans had been told, “If war comes to Poland, you will all be hanged.” This prophecy was later fulfilled in many cases.[24]

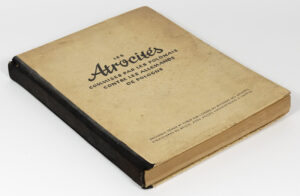

The famous bloody Sunday incident in Toruń on September 3, 1939, was accompanied by similar massacres elsewhere in Poland. These massacres brought a tragic end to the long suffering of many ethnic Germans. This catastrophe had been anticipated by the Germans before the outbreak of war, as reflected by the flight, or attempted escape, of large numbers of Germans from Poland. The feelings of these Germans were revealed by the desperate slogan, “Away from this hell, and back to the Reich!”[25]

American historian Dr. Alfred-Maurice de Zayas writes concerning the ethnic Germans in Poland:[26]

“The first victims of the war were Volksdeutsche, ethnic German civilians, resident in and citizens of Poland. Using lists prepared years earlier, in part by lower administrative offices, Poland immediately deported 15,000 Germans to Eastern Poland. Fear and rage at the quick German victories led to hysteria. German ‘spies’ were seen everywhere, suspected of forming a fifth column. More than 5,000 German civilians were murdered in the first days of the war. They were hostages and scapegoats at the same time. Gruesome scenes were played out in Bromberg on September 3, as well as in several other places throughout the province of Posen, in Pommerellen, wherever German minorities resided.”

Hitler had planned to offer to restore sovereignty to the Czech state and to western Poland as part of a peace proposal with Great Britain and France. German Minister of Foreign Affairs Joachim von Ribbentrop informed Soviet leaders Josef Stalin and Vyacheslav Molotov of Hitler’s intention in a note on September 15, 1939. Stalin and Molotov, however, sought to stifle any action that might bring Germany and the Allies to the conference table. They told Ribbentrop that they did not approve of the resurrection of the Polish state. Aware of Germany’s dependency on Soviet trade, Hitler abandoned his plan to reestablish Polish statehood.[27]

Conclusion

Hitler’s invasion of Poland was forced by the Polish government’s intolerable treatment of its German population. No other national leader would have allowed his fellow countrymen to similarly suffer and die just across the border in a neighboring country.[28] Germany did not invade Poland for Lebensraum or any other malicious reason.

However, even British leaders who had worked for peace later claimed that Hitler was solely responsible for starting World War II. British Ambassador Nevile Henderson, for example, said that the entire responsibility for starting the war was Hitler’s. Henderson wrote in his memoirs in 1940:[29]

“If Hitler wanted peace, he knew how to insure it; if he wanted war, he knew equally well what would bring it about. The choice lay with him, and in the end the entire responsibility for war was his.”

Henderson forgot in this passage that he had repeatedly warned Halifax that the Polish atrocities against the German minority in Poland were extreme. Hitler invaded Poland in order to end these atrocities.

Endnotes

| [1] | Roland, Marc, “Poland’s Censored Holocaust,” The Barnes Review in Review: 2008-2010, p. 131. |

| [2] | Roberts, Andrew, The Storm of War: A New History of the Second World War, New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2011, pp. 18-19. |

| [3] | Evans, Richard J., The Third Reich at War 1939-1945, London: Penguin Books Ltd., 2008, p. 11. |

| [4] | Barnett, Correlli, The Collapse of British Power, New York: William Morrow, 1972, p. 560; see also Taylor, A.J.P., The Origins of the Second World War, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1961, p. 211. |

| [5] | Shadewaldt, Hans, Polish Acts of Atrocity Against the German Minority in Poland, Berlin and New York: German Library of Information, 2nd edition, 1940, pp. 75-76. |

| [6] | Hoggan, David L., The Forced War: When Peaceful Revision Failed, Costa Mesa, Cal.: Institute for Historical Review, 1989, pp. 260-262, 387. |

| [7] | Ibid., pp. 452-453. |

| [8] | Ibid., p. 554. |

| [9] | Day, Donald, Onward Christian Soldiers, Newport Beach, Cal.: The Noontide Press, 2002, p. 56. |

| [10] | Hoggan, David L., The Forced War, op. cit., pp. 358, 382, 388, 391-92, 479. |

| [11] | Ibid., pp. 500-501, 550. |

| [12] | Ibid., pp. 509-510. |

| [13] | Ibid., p. 509 |

| [14] | Barnes, Harry Elmer, Barnes against the Blackout, Costa Mesa, Cal.: The Institute for Historical Review, 1991, p. 222. |

| [15] | Ibid., pp. 227, 249. |

| [16] | Jong, Louis de, The German Fifth Column in the Second World War, New York: Howard Fertig, 1973, pp. 36-37. |

| [17] | Ibid, p. 37. |

| [18] | Hoggan, David L., The Forced War, op. cit., p. 419. |

| [19] | Irving, David, Goebbels: Mastermind of the Third Reich, London: Focal Point Publications, 1996, p. 304. |

| [20] | Hoggan, David L., The Forced War, op. cit., p. 419. |

| [21] | Ibid., p. 396. |

| [22] | Grenfell, Russell, Unconditional Hatred: German War Guilt and the Future of Europe, New York: The Devin-Adair Company, 1954, p. 86. |

| [23] | Ibid., pp. 86-87. |

| [24] | Hoggan, David L., The Forced War, op. cit., p. 390. |

| [25] | Ibid. |

| [26] | De Zayas, Alfred-Maurice, A Terrible Revenge: The Ethnic Cleansing of the East European Germans, 2nd edition, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p. 27. |

| [27] | Tedor, Richard, Hitler’s Revolution, Chicago: 2013, pp. 160-161. |

| [28] | Roland, Marc, “Poland’s Censored Holocaust,” The Barnes Review in Review: 2008-2010, p. 135. |

| [29] | Henderson, Sir Nevile, Failure of a Mission, New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1940, p. 227. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 2022, Vol. 14, No. 3. A version of this article was originally published in the May/June 2022 issue of The Barnes Review.

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a