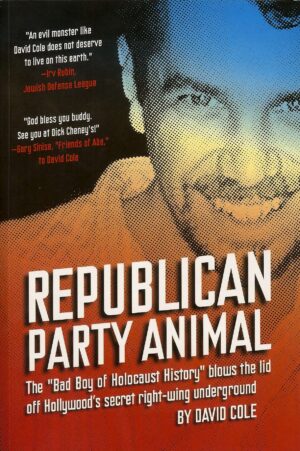

Republican Party Animal

A Review

Republican Party Animal, by David Cole, Feral House, Port Townsend, WA, 2014, 319 pp.

Republican Party Animal is a layered chronicle of David Cole’s short but storied public career as a “Jewish Holocaust denier” and of his equally unlikely “second life” as David Stein, when he would come to play an influential role as an event organizer and Op-Ed dynamo among the guarded ranks of Hollywood conservatives before having his heretical past exposed by a vindictive ex-girlfriend. The dual biographical narratives converge in a morally conflicted tale of downfall and personal reinvention, of intersecting identities and of consequences wrought in the whirlwind momentum of a life less ordinary.

Cole’s telling is breezy, surefooted, and entertaining throughout; he gives the impression of a natural raconteur, punctuating his episodic memoir with revealing anecdotes, ironic observations, and self-effacing humor, all while providing the kind of sympathetic yet critical discussion of Holocaust revisionism that, coming from a reputable imprint with wide distribution, is rare if not unprecedented.

“I will most likely come off as an asshole in this book,” Cole announces at the outset. And while I suspect that will indeed be the conclusion of certain readers (including one well known magazine editor who has since threatened legal action), it isn’t mine.

No Country for Jewish Revisionists

Cole’s curious – and curiosity-driven – initiation into the intellectual quick (though never the dominant political culture) of Holocaust revisionism started off, as he tells it, “innocently enough,” in the late 80s as a capricious detour during his youthful adventures train-hopping political movements for kicks and edification. Being intrigued by IHR co-founder David McCalden’s category-defying ideological profile as “a militant atheist, an Irish nationalist, and a Holocaust revisionist,” Cole wrote to him asking for literature and information. When McCalden instead showed up at Cole’s doorstep in full-on confrontational mode (he thought Cole was “a ‘Jewish infiltrator’ trying to cozy up to him for nefarious purposes”), Cole assured him that he was sincere and there was an apparent meeting of minds. Following this encounter, Cole read McCalden’s hand-picked literature and found it to be “[i]ncredibly amateur crap.” Yet he was left with questions. “The problem” he discerned, was that “mainstream historians would never address revisionist concerns, and the revisionists, for the most part, were sloppy and (mostly) ideologically motivated.”

Preoccupied, Cole soon went to visit McCalden, only to receive the news that the guy had died of AIDS, leaving behind a massive collection of books and private correspondence that, by default, fell into Cole’s possession. Whatever inchoate doubts or questions Cole had entertained about the standard Holocaust historiography, it seems fair to surmise that his “identity” as a non-dogmatic Holocaust revisionist crystallized in the months-long binge of immersive reading that followed. I imagine it was with some nostalgia that Cole recalls his underground education:

I rented an apartment with two stories so that I could devote one entire floor just to the books. And I read every single one of them, making notes, bookmarking pages, and indulging in what would become, in less than a decade, the lost art of reading hard-copy books without a computer in sight.

By the early to mid-90s, Cole would be riding a wave of public notoriety as an intrepid, Hollywood-bred independent researcher and documentary filmmaker making the rounds on daytime TV talk shows professing informed skepticism about the received history of the Holocaust. In those days, which I remember too well, Cole could be seen alongside IHR spokesman Mark Weber on the Montel Williams Show (where, in an ironic twist recounted in Republican Party Animal, his appearance led to the reunion of two Holocaust survivors – brothers who had lost contact after the war, each assuming the worst about the other’s fate). He appeared with CODOH founder Bradley Smith and Skeptic editor Michael Shermer on a rather tense episode of Donahue. He even went on the Morton Downey Junior Show, where he suffered the late host’s outrageous nicotine-expectorating spleen with pluck.

The first and most conspicuous thing that distinguished Cole from other Holocaust revisionists (as they were still referred to in those days, when the artifice of civility had yet to give way to the “denier” shibboleth), was, of course, the fact that he was, perhaps more than nominally, Jewish. Cole’s Jewish identity was at once a hook and a problem. On the one hand, his Jew-cred ingratiated him to many revisionists who understandably wanted, for the most part sincerely, to disassociate their work from the thick funk of anti-Semitism that surrounded it. On the other hand, the specter of a “Jewish Holocaust revisionist” rankled the guardians of orthodoxy for whom the public image of a Jewish gas chamber skeptic presented a dangerous rift in a carefully crafted Manichean narrative that had long served to marginalize and stigmatize – and across certain borders, criminalize – critical engagement with what I like to call “the other side of genocide.”

But it wasn’t all talk-show theater. Because the second, and ultimately more important, thing that set Cole apart from other revisionists was his knack for getting his hands dirty. He conducted – and documented – on-site investigations in the “Holiest of Holies” where the worst conveyor-belt atrocities were believed (“by all the best people” as Bradley would have it) to have gone down. Cole’s groundbreaking guerilla Auschwitz documentary, David Cole Interviews Dr. Franciszek Piper remains a case in point. Rather than simply lay contextualizing narration over the usual stock footage of marching brownshirts and bulldozed corpses, Cole did what other revisionists, a few notable exceptions notwithstanding, would not – and to be fair, could not – do; he visited ground-zero and critically examined the physical structure of what was then presented to tourists as a homicidal gas chamber in its “original state.” Cole put questions to the museum staff and even scored a groundbreaking interview with then-curator Dr. Franciszek Piper – who, at little prompting, admitted what revisionists alone had long contended – that the “gas chamber” displayed to tourists as the genuine article was in fact a postwar “reconstruction” (though of course, revisionists would more likely call it a “fake”). While other revisionists buried their noses in books (which is, of course, important), Cole took matters into his own hands. He was inquisitive. He was tenacious. He was clever. And just as important, he had the testicular brass – and the “Jew face” – to go where others feared to tread.

To Phil Donahue, Cole was “the Antichrist” (seriously, Donahue called him that, to his face!). To professional “Skeptic” Michael Shermer, he was a “meta-ideologue,” or what we might now call a high-functioning troll, who reveled in the role of the contrarian, stirring up trouble “for the hell of it.” To revisionist king-of-the-mountain Robert Faurisson, he was a dangerous upstart, a loose cannon who couldn’t be trusted to toe the line. To Irv Rubin – crucially, the late Irv Rubin – David Cole was something worse.

Cole’s history with the man whom, from the other side of eternity, he describes as the “lovable and murderous head of the Jewish Defense League” began in a violent altercation when Rubin tried to shove Cole down a section of stairs at a 1991 UCLA speaking engagement. It ended, more or less, a few years later when a threat of mortal violence changed the course of Cole’s life. The pivotal turn – or plot point, since we’re in Hollywood – came in late 1997, when, for a variety of reasons, Cole had more or less absconded from his public dalliance with revisionism. That’s when, “[f]or reasons known only to him,” Rubin took to the nascent World Wide Web to place a $25,000 bounty on Cole’s head.

Evoking the lurid prose-style of a forgotten dime-store pulp novel, Rubin’s accompanying screed described Cole as “a low-lying snake that slithers from dark place to dark place, [spreading] his venom to innocent victims.” And when Rubin fulminated that “an evil monster like this does not deserve to live on this earth,” it wasn’t mere bluster; it was an incitement. Rubin had long been suspected of (and has since been implicated in) a number of arson attacks and fire bombings directed against revisionists and revisionist organizations so there was every reason to believe that he – or more likely one of his psychotic JDL lackeys – might rise to the task. Like the leader of some torch-wielding mob in an old horror film, Rubin wanted to kill the monster, not metaphorically, but literally. And he offered cash money to anyone who would do the bloodwork or provide information to make it easier. “This world would be a happier place, indeed,” the avuncular zealot declared, “when all the Jew-baiters and Jew-haters have disappeared, especially the most vicious hater of them all, David Cole.”

But the event proved to be fateful rather than fatal. There’s been a good deal of hazy speculation over just what happened, with some people, myself included, speculating that Cole’s subsequent “recantation” (such a silly word to use in the 21st century) was ghostwritten by Rubin and signed under duress, and with others suspecting that Cole’s public declaration might have been, if not sincere, at least in line with what seemed to be his increasingly ambivalent stance toward revisionism. The truth as revealed in Cole’s book, is shaded grey.

In short, Cole took the threat seriously. He considered going to the police but rejected that option because of the unwanted publicity it would entail. In the end, he opted to simply call up his bête noir and offer up an unequivocal, notarized recantation in exchange for his life. He wrote it himself. It was bullshit, of course, but it also provided a way out. A clean break from the public existence he had entered with perhaps too much reckless disregard for what might follow.

In Republican Party Animal he is clear that “The recantation was Cole’s ‘death.’ ”

“I had already left revisionism, so I figured why not ‘kill’ Cole, especially if it saves my actual hide. Once someone like Cole recants, there’s no going back. Your credibility is shot. If you try to recant your recantation, people will always wonder, ‘was he lying then, or is he lying now?’ I agreed to the recantation not just to get the bounty removed, but to burn all Cole bridges. I knew that the revisionists who were already getting pissed at me in 1995 would truly hate me when they read what I gave Rubin. I wanted to ‘kill’ Cole in a way that would make it impossible for me to go back.”

But David Cole didn’t die, literally or figuratively. It might be more accurate to say that he receded, only to resurface as the script demanded. It remains an open question whether Cole’s ensuing life adventure resolves in measures of liberation and redemption or in desolation and ruin. Unlike a Hollywood script, life isn’t so tidy.

Toasting Team America

As the curtain closes on the first act, Cole finds himself in a funk, “limping back to square one.” When a fashion-mad actress-girlfriend leaves him spiraling in debt, he spends some time “pining and whining” before eventually moving on to some shady but apparently lucrative Internet business ventures where he cynically leverages his by-then-encyclopedic knowledge of Holocaust history to play “both sides” for what financial gain could be had. Having for practical reasons already adopted his new identity as “David Stein,” he invents other pseudonyms – “one to sell books and videos to Holocaust studies departments around the world, and one to sell books and videos to revisionists.” And the vultures, from both sides, take the bait.

Cole’s account of what might be considered his transitional phase is tinged with moral ambivalence and, ultimately, regret. “The truth is, I can’t defend it,” he writes at one point.

“The only thing I can say is that after I was forced out of the field by the death threats of the JDL and the lies of people like Shermer [more on Michael Shermer later – CS], I had to emotionally divorce myself from the subject matter […] unlike my revisionist work, which I’ll still defend, and unlike my conservative work, which I’ll still defend, I can’t defend the period in between.”

Following this episode, Cole soon walks into another bad relationship, adopts yet another name (“David Harvey,” if you’re keeping track), and pulls off another death-faking caper, this time to escape the physically abusive clutches of a woman he now refers to only as “the Beast.” Then he goes off the grid, ensconcing himself in the beach city environs of El Segundo, where he soon becomes restless. Teaming up with a fellow film editor referred to as “Fat Frank,” Cole eventually re-enters his old turf to do some shadow revisionist – or quasi-revisionist – work, shooting a still-unreleased interview with Mel Gibson’s dad (!), making a short documentary about the persecution of Ernst Zündel and Germar Rudolf, and ghostwriting an important free-speech manifesto entitled “Historians Behind Bars.”

In the course of “one thing leads to another,” Cole’s friendship with Fat Frank leads to a friendship with actor Larry Thomas, best known for his role as the “Soup Nazi” on Seinfeld, which leads to a relationship with a blonde vixen, which leads to a bout with erectile dysfunction, which leads, fatefully, to yet another bad bet romance, this time with a “six-foot-tall redhead with an amazingly big smile” named Rosie – the actress-model who would eventually play a key role in blowing David Stein’s cover. If Republican Party Animal were film noir, I guess Rosie would get billing as the femme fatale – except that by most accounts she was bad news from the start. One inescapable conclusion to be gleaned from Republican Party Animal is that David Cole has abominably bad judgment when it comes to the ladies.

While Cole’s introduction to revisionism is clearly delineated in Republican Party Animal, it is somewhat less clear how he came to identify as a “South Park conservative.” He provides a hint that the Left’s shambolic response to the end of the Cold War in 1989 might have been a germinal factor, but it is almost in passing that he mentions, in a prelude to a discussion of his involvement (working with the legendary Budd Schulberg) in the restoration of Pare Lorentz’s 1946 documentary Nuremberg, that he had “over the years” somehow found time to pen a number of conservative (mostly anti-Islamist) op-eds for the L.A. Times under yet another “revolving series of pseudonyms.”

The lack of a clear-cut conservative origin story is a point of minor frustration for me if only because during my brief correspondence with Cole in the mid-90s, I had come away with the impression that he identified as a liberal. Maybe it was his abortion rights activism, or maybe it was his outspoken atheism (which he now disavows, also without much explanation) that tripped me, but when the stories broke about l’affaire Cole-Stein, my first thought was: David Cole is a Republican?

No matter, Cole seems sincere. “I don’t mind being defined by what I’m against,” he explains, “And I’m against the left.” More insightfully, he goes on to distinguish ideology from principle:

“Principle is not the same as ideology. As an example, Islamism—the set of beliefs adhered to by Muslims who want to impose their worldview on others—is an ideology. But opposition to Islamism isn’t necessarily an ideology. It can be, but not by necessity. One can oppose banning women from voting or driving on principle. You can be right, left, moderate, or totally apolitical, and still, on principle, say ‘that’s a bad and oppressive idea.’ The fact that I dismiss ideology and ideologues doesn’t mean I don’t have principles, and it doesn’t mean that I don’t care passionately about them. And, generally speaking, the right side of the spectrum, more often than not, reflects my principles.”

Fair enough, then. Cole is a conservative as a matter of principle, not as a matter of dogma. He’s more PJ O’Rourke than Russ Kirk. More Hayek than Rand. I get it. I even sort of agree.

The same hands-on approach that had distinguished Cole’s career as a revisionist researcher would prove instrumental in guiding his meteoric rise in the demimonde of Hollywood conservatives – or “Friends of Abe” as he came to know them. So successful was he in navigating this semi-secretive social network that after proving his mettle as a party organizer in various settings he would brand his own offshoot organization, the “Republican Party Animals,” hosting liquor-doused GOP fundraisers that were attended by outspoken and semi-closeted right-wing celebrities, pundits, and proles.

Cole took careful notes along the way and while I suppose his insider’s account of so many soirees and mixers will be chum for certain political junkies, I personally would have preferred more in the way of a sketch. As it stands, Cole’s reminiscences about this period of his life seem burdened by a surfeit of anecdote – too much detail at all turns, too much dwelling on interpersonal contretemps. But while I can’t shake the sense that a measure of time and distance would have advised finer editorial discretion, the truth is I have yet to read an autobiography that doesn’t suffer from this tendency. It may be that the occasional pangs of boredom I felt in reading Cole’s play-by-play can be chalked up to selective incuriosity. I felt the same way about Jim Goad’s Shit Magnet, and Goad is one of my favorite writers.

Telling All

The Feral House promotional copy pitches Republican Party Animal as a kind of inside-politics-inside-Hollywood tell-all. And indeed, there’s scuttlebutt on offer if that’s your fix.

On the revisionist side of the aisle, we learn, or we are reminded, that David McCalden – the guy who played a formative role in introducing Cole to revisionist theory – was a sexual as well as intellectual outlaw who gave his wife AIDS (before dying of it himself) back when a viral load meant a one-way ticket to the morgue. We learn – or we are reminded – that Robert Faurisson, was sufficiently pin-pricked by Cole’s ungovernable audacity that he huffed and puffed and spread rumors that Cole was a “World Jewish Congress infiltrator.” (Cole’s grave sin, incidentally, was to break with revisionist dogma by broadcasting his opinion that the Natzweiler gas chamber in France, unlike those on display at Auschwitz, Mauthausen, Dachau, etc., was the real deal, albeit a highly eccentric outlier in the scheme of the received mass-gassing narrative.)

Aside from such morsels, however, Cole’s recollections about his exploits among the maligned revisionist milieu are mostly reflective, evenhanded, and often fond. He gives David Irving due credit as a once-formidable narrative historian with a narcissistic penchant for self-sabotage. He expresses warm regard for CODOH-founder Bradley Smith (“we don’t agree on everything, but he’s a lifelong friend”), and his thoughts on certain egregiously persecuted revisionists (or, in some instances, “deniers”; Cole insists upon the distinction) are presented with judicious attention to the underlying free-speech travesty that somehow still eludes many outspoken civil libertarians. Ernst Zündel (whom Cole describes as a “denier,” again if you’re keeping a ledger) is a good example. Cole appraises the repeatedly imprisoned German-Canadian pamphleteer as a harmless crank who “really loves Hitler,” yet he channels Voltaire in voicing unqualified support for a man who has spent a significant part of his adult life behind bars, often in solitary confinement, for what can only be described as thoughtcrime. “I never said anything in support of his views,” Cole writes, “but I supported his right to be free from prosecution for simply writing a book, and I still do. On that subject, I’d stand with him again today.” Cole is equally resolute in his defense of Germar Rudolf (“revisionist”), a German chemist who was extradited from his legal residence in the United States to be locked up for years in a German cell, all for the “crime” of writing about blue stains on old concrete.

Turning to the celebrities and politicos on the other side of the aisle, Cole’s grievances are moderate, and his gossip is less salacious than I would have expected. John Voight comes off as a harmless lush. Gary Sinese is a “mensch” with some unknown skeletons in his closet. D-listers Pat Boone and Victoria Jackson are unsurprisingly depicted as conspiracy-mongering loons. Clint Eastwood is aloof in a good way. Kelsey Grammer is aloof in a creepy way. David Horowitz is described as “a huge dick” who “reacts to a request to shake hands as most men would to a request to grab the penis of a rotting corpse.” There’s a blowjob story featuring Oliver Stone’s batshit crazy son. There’s a funny story about Michael Reagan’s war on gophers. And, yeah, it turns out that Cole’s deadbeat dad was “apparently” the doctor who served Elvis that fatal dose of Demerol. Gotta mention that.

You might think that Cole’s harshest score-settling would come in for Rosie and the Lolita-chasing neocon-cum-Disney-scripting hack with whom she tag-teamed to out David Stein as a Holocaust denier … in which case you would have another think coming. Because the dirtiest dirt in Republican Party Animal is reserved not for the people who exposed Stein as Cole (nor for Irv Rubin, the man who tried to have Cole murdered), but for an accused rapist (as Cole never tires of emphasizing, for reasons more subtle than they first appear) who has for some time served as “the media’s go-to guy for the selective skepticism of hipsters who hang out in coffee shops in Silverlake.”

Let’s warm up with a bit that made me laugh:

“After Shermer contacted me, we hung out a few times. The first time I was at his house, he asked me if I’d like any coffee. I drank coffee religiously in those days (my pre-alcohol days), so I said yes. And Shermer proceeded to re-heat a pot of coffee that was stone cold, presumably brewed that morning, hours ago.

‘Uh, can you maybe brew up some fresh?’

‘No need, it’s just as good reheated.’

Sometimes, it’s the little things that matter as much as the big ones when you’re trying to gauge someone’s intelligence. Here was a supposed ‘scientist’ with no concept of how fresh-brewed coffee gets worse when it gets cold.”

Cole goes on to describe Skeptic editor Michael Shermer as “one of the most dishonest human beings I have ever known,” and he has the goods – specifically transcripts of recorded phone conversations – to back up his spleen. It’s little surprise that Shermer unleashed his lawyers in an unsuccessful bid to prevent Cole’s book from being published. What’s more surprising is that the man still enjoys his inflated reputation after being so thoroughly exposed as a mendacious opportunist who repeatedly betrayed and libeled Cole and who has deceitfully misrepresented his – and other revisionists’ – work at every conceivable turn. I won’t go into detail about just what dirt Cole has against “Shermy,” but I will say that his prolonged and hyper-documented animadversion is worth the cover price.

So, there’s juice for those who come a-lookin’. Some of it may be petty, but some of it is well justified and even newsworthy. Still, I would politely insist that the “tell-all” aspect of Republican Party Animal ultimately amounts to a wink-sly bait-and-switch. Cole’s thematic gravamen, tucked between so much confessional digression and tittle-tattle, concerns the burden of conscience and a man’s abiding struggle to maintain a modicum of personal and intellectual integrity while inhabiting two worlds where cynicism and suspicion hold sway.

Cole’s story is thus laced with insight bearing on such threads of connective tissue that, moral equivalence be damned, unite revisionism with movement conservatism. When Cole dwelled in revisionist circles, he inveighed against Faurisson-branded “No holes, No Holocaust” rhetoric and pled for sanity against the seductive force of sundry conspiracy theories. When Cole dwelled in the world of conservative politics, he found himself in the same futile rut, taking pubic issue with Breitbart-branded trench warfare tactics and pleading for sanity against the seductive force of sundry conspiracy theories. “I’d rather gouge out my testicles,” Cole quips, “than accept the accolades of the lunatic fringe.”

Whether you find the tone colorful or off-putting will be a matter of taste, but I think Cole is especially good on this front. One of my longstanding gripes with movement revisionism (I pay less attention to movement conservatism) is that it blends too easily with rank crackpottery. The revisionist affiliation with – and tacit affinity for – various threads of wildly conspiratorial speculation may be understandable when we consider that respected World War II scholars have largely been driven away by very real threats of prosecution and ruinous public censure, but in the atmosphere that prevails under a black cloud of taboo the loudest voices tend to be the looniest. It’s an insidious catch-22 that in turn makes it only too easy for consensus-mongering guys like Michael Shermer to paint the whole project in broad strokes as a manifestation of hate-fueled paranoia. Cole puts the matter more bluntly when he notes that “[c]leaning up flaws in the historical record after a major event like a world war is not the same as claiming that all 27,000 residents of Newtown decided to fake a mass shooting.”

While I may not share Cole’s explicitly “pro-Zionist” views, it is thus without qualification that I endorse his stridently expressed contention that:

“The people who think that revising the history of the Holocaust will somehow topple Israel are idiots. Israel’s existence is not based on whether or not there were gas chambers at Auschwitz in 1944. If, tomorrow, Yad Vashem declared that Auschwitz had no killing program, it would not make one damn bit of difference. Israel would be fine, because Israel’s Muslim foes don’t give a good fuck about historical subtleties. No one in the Muslim world is studying forensic reports, thinking ‘if I can’t find traces of cyanide residue in the Auschwitz kremas, I’ll hate Israel and try to destroy her. But if I can find the traces, by gosh, I’ll love and support her.'”

We are faced with a subject so clung up with emotive gravity that Cole’s elementary defense of disinterested inquiry is difficult for people to grasp, which is why it bears repeated emphasis. There is nothing inherently hateful or even political about revisionist research. This is fundamentally true regardless of what personal motives impart to individuals who persist in such research, and it is fundamentally true regardless of what political arguments or agendas may latch to such research. While motivated ideologues can be counted on to use revisionist scholarship as a cudgel against their imagined enemies, the underlying investigative project is simply and eternally a thing apart; it is an empirical and interpretive process that, once the fog has lifted, will be judged on its relative merits and deficiencies – the same as with other “problematic” species of skeptical inquiry, such as concerning racial differences or climatology or various aspects of human sexuality. Once this much is understood, it becomes possible to distinguish the substantive core of revisionism from the cranked-up clamor that invariably surrounds it.

Being wise to this difficulty, Cole anchors his own interpersonally fraught micro-history of foibles and resentments to the project of historiography writ large. A memorable passage taps the messy truth:

“[…] in every massive conflict between nations you see the exact same things that occur in conflicts between individuals—the same jockeying and maneuvering, the same collecting and testing of loyalties, the same measuring of risk against gain. The difference is only the scale. I used to make that point when I lectured. Never elevate or excoriate historical figures to the extent that they stop being flesh-and-blood humans. Don’t make Hitler the devil, and don’t make the Founding Fathers gods. They were still human, no matter their impact on history.

Is the task really so difficult? I’m afraid it is. Humanity is long in the weeds, and we are burdened with heavy baggage. For all his sarcasm and ventilation, Cole ends up counseling humility before the big questions. Who will notice?

Gas in the Gaps?

Given his past investment in the subject, it’s a safe bet that many readers will be interested in David Cole’s present take on Holocaust history and revisionism. Although he expresses understandable reluctance about holding court on the subject anew, the truth is that Cole is never more in his element than when he writes about history. He’s attentive to detail and he presents his theses logically in clear language that stands in welcome contrast to the palaver-laden cant of certain professional obscurantists. He would be a good teacher.

Revisionism comes up at tangential and direct turns throughout the biographical narrative – significantly in “The Idiot’s Creed,” which provides a fascinating account of Cole’s “behind the scenes” interactions with a number of prominent public figures during his revisionist days – but Cole’s present views are explicitly teased in an early chapter none-too-subtly entitled “So Just What the Hell Do I Believe, Anyway?” and are more carefully developed in a 24-page appendix that should be of special interest to traditional Holocaust historians and revisionists alike.

The unavoidable headline is that Cole stands by his early research, rejecting the standard claim that Auschwitz and many other infamous camps served as killing centers equipped with homicidal gas chambers. “Auschwitz was not an extermination camp,” he writes:

“Auschwitz and Majdanek in Poland, and Dachau, Mauthausen, and the other camps in Germany and Austria, were not extermination camps. They were bad, bad places. People were killed there. Jews were killed at Majdanek by shooting, and Jews were killed at Auschwitz in 1942, most likely due to decisions made by the commandant in defiance of orders from Berlin.”

In the following paragraph, Cole writes:

“However, Auschwitz was not the totality of the Holocaust. Not by far. Serious revisionists (David Irving, Mark Weber, and hell, I’ll throw my own name in there) don’t dispute the very provable mass murder of Jews (by shooting) during the months following the invasion of Russia. And at a camp like Treblinka, there is a massively strong circumstantial case to be made that the Jews who were sent there were sent there to be killed. It’s circumstantial because very little remains in the way of documentation, and zero remains in the way of physical evidence. But revisionists have never produced an alternate explanation of the fate met by the Jews sent to camps like Treblinka and Sobibor, with empty trains returning. However, accepting that Treblinka was a murder camp but Auschwitz wasn’t means that the Holocaust was not as large in scale or as long in operation as the official history teaches. So taking Auschwitz out of the category of extermination camps is seen as lessening the horror of what, even shorn of Auschwitz, was still a horrific situation.”

While Cole’s summary may come laced with a bit more anti-Nazi editorial invective than is typically found in the currents of dissident Holocaust scholarship, his take on the history of Auschwitz in particular pretty much distills to a grounded recitation of revisionist theory, at least insofar as he rejects the standard claim that the site was renovated to be an ever-efficient killing factory during the latter phase of the war. In his more detailed treatment, where Jean-Claude Pressac’s work figures prominently, he deftly summarizes myriad forensic and chronological problems to advance the openly revisionist conclusion that the most infamous extermination camps were nothing of the kind.

And in case anyone other than Phil Donahue still believes the propaganda about the Dachau “gas chamber,” Cole is at the ready with a sobriety check:

“Eventually, by the 1970s, the Dachau museum admitted that the ‘gas chamber’ was never used. The fact that the ‘phony shower heads’ were created by the army prior to the visit of U.S. dignitaries in ’45 is the biggest open secret in the field. The current claim at Dachau is that the room was ‘decorated’ with dummy shower heads, which replaced the real shower heads and thus made them useless, in order to fool the victims, and once they were inside, gas pellets were thrown in from chutes in the side wall. And the half-measure ‘revision,’ that the chamber was ‘never used,’ really needs to be meditated on for a moment to grasp its stupidity. We’re supposed to believe that the Nazis took a working—and very necessary—group shower room at the camp, and replaced the working shower heads with fake ones, because they wanted to fool the victims into thinking they were walking into a shower room, which they would have thought anyway if the original shower heads had simply been left intact, and then the Nazis decided not to ever use the gas chamber, but now the room was unusable as an actual shower because the real shower heads had been replaced by fake ones, fake ones that were supposedly necessary to fool victims into thinking that they were walking into a shower room which is exactly what the victims would have thought without the fake shower heads because the room actually was a shower room which could have still been used as one in between gassings if not for the dummy heads that replaced the genuine ones.”

If you want a down-and-dirty distillation of Cole’s current views, the most tightly packed summation is probably provided in the following two paragraphs:

“The evidence of the mass murder of Jews was largely buried or erased by the Nazis long before the end of the war. At the war’s end, what was there to show? What was there to display? And something had to be displayed. World War II is a war with an ex post facto reason for being. The war started to keep Poland free and independent. At the end of the war, when Poland was essentially given to the USSR as a slave state (not that there was much the U.S. could have done to stop it from happening), none of the victorious powers wanted folks to start asking, ‘wait—sixty million people dead, the great cities of Europe burned to the ground, all to keep Poland free, and now we’re giving Poland to Stalin?‘

So Hitler’s very real brutality against the Jews had to become ‘the reason we fought.’ Except, those brutalities began in earnest two years after the war started. But why quibble? Russia had captured Auschwitz and Majdanek intact (more or less), and the U.S. had captured Dachau totally intact. So, those camps became representations of a horror for which almost no authentic physical evidence remained. At Auschwitz, an air raid shelter was ‘remodeled’ to look like a gas chamber (as the museum’s curator admitted to me in a 1992 interview). At Majdanek, mattress delousing rooms were misrepresented as being gas chambers for humans (as the museum’s director admitted to me in 1994). And at Dachau, the U.S. Army whipped up a phony gas chamber room to give visiting senators and congressmen in 1945 a dramatic image of ‘why we had to fight.’”

Attentive readers will note how Cole, at certain points in the above-cited excerpts, parts company with many revisionists. This is made clearest in the appendix, where, in a nuanced counterpoint to the long-rehearsed revisionist emphasis on lack of a clearly discoverable “master plan” authorizing the wholesale extermination of Europe’s Jewish population, Cole plausibly argues that there were actually a congeries of “plans” floated and hatched at various stages in the wake of the infamous (and still profoundly misunderstood) Wannsee “protocols,” with such plans being molded by shifting goals and expediencies as the Nazis pursued an overarching yet decentralized injunction to resolve the “Jewish question” one way or another with only instrumental regard for the welfare of Jewish people. Sometimes this meant the exploitation of Jewish labor. Sometimes it meant the mass transfer or “evacuation” of populations. And sometimes it meant mass killing, including by gassing.

From this vantage, Cole focuses on the question of intent, discerning clues in the sequence of contemporaneous communications and pronouncements, many culled from Joseph Goebbels’s writings, to support his conjecture that for a time – specifically from “1942 through 1943” – Jews were dispatched to genuine extermination camps, specifically “Treblinka, Sobibor, Belzec, and Chelmno,” otherwise known as the Aktion Reinhardt system, where they were lined up and shot, or, in classic Holocaust style, queued up and fed to gas chambers (albeit of the truck-rigged must-have-been-carbon-monoxide-not-diesel-exhaust variety, not the pellet-inducted Zyklon B variety) and then burned (in pits, not crematoria).

Anyway, here’s the money shot:

“From 1942 through 1943, Polish Jewry was subjected to one of the most brutal campaigns of mass murder in human history. Because of the secrecy surrounding those four extermination camps, and the fact that they were ploughed under and erased from existence in 1943, it’s difficult to be precise about certain details. And we do know that some Jews were sent to those camps as a throughway to other destinations (as recounted multiple times in Gerald Reitlinger’s 1953 masterwork The Final Solution). But, more than enough circumstantial evidence exists to show that for most Jews, the train ride to those camps was one-way, and final.”

Not being an historian (and not having the constitutional fortitude for serious historical research), I will leave it to revisionist scholars to engage Cole’s interpretation of the timeline, the documentary mens rea and such other circumstantial evidence that might or might not support the conclusion that the eastern camp system served for a time as a full-on gas-and-burn death factory. I’m confident they’ll have plenty to say, since this whole area seems to have assumed prominence as the focal point of revisionist (and anti-revisionist) critique over the past decade or so, as evidenced by the widely viewed video documentary, One Third of the Holocaust, by the forensic researches of Fritz Berg, and by the voluminous output of guys like Germar Rudolf, Carlo Mattogno, Thomas Kues, Jürgen Graf and others, often in rebuttal to the mud-slinging gang of anti-revisionist gadflies over at the “Holocaust Controversies” site. Cole may not have come looking for an argument, but he’ll have one if he wants it. One can only hope that the debate, if it comes, will proceed with a modicum of civility. Whether Cole’s argument is sincere or tactical (and I’m inclined to believe he is sincere), it should be received as an invitation for revisionists to clarify and supplement their mounting counterargument in a spirit of good faith.

Regardless of how it will be met among active revisionists, I am sure that Cole’s argument will seem positively baffling to the average reader who has been groomed to regard Auschwitz as synecdoche for the canonical Holocaust story. While it may be understood that Cole is correct when he points out that “Auschwitz was not the totality of the Holocaust,” ordinary readers who come to Republican Party Animal with the usual engrained preconceptions will be hard-pressed to digest his “gas in the gaps” counter-narrative. I imagine it will be a bit like being told that yes, there was a Battle of the Alamo, but it actually took place in North Dakota!

No matter where the chips fall, I do think that Cole’s “exterminationist” interpretation of the Aktion Reinhardt system is superficially plausible and therefore useful. Whether it can withstand more intensive scrutiny is a different matter. Being a dilettante at best, I can only say it’s not how I would bet. Presumably for reasons of brevity, Cole neglects to directly address the copious revisionist literature in this area, so when he states that “revisionists have never produced an alternate explanation of the fate met by the Jews sent to camps like Treblinka and Sobibor, with empty trains returning” I am left to wonder whether he has read Samuel Crowell’s carefully documented treatment of the Aktion Reinhardt camps in the Nine-Banded Books edition of The Gas Chamber of Sherlock Holmes. For what it’s worth, the relevant discussion is framed in the seldom-read fourth part of Crowell’s book, “The Holocaust in Retrospect,” where – I’m trying to save everyone time here – the most succinct statement of an “alternate explanation” (though Crowell would probably call it an “interpretation”) is advanced in the fifth section, “Aktion Reinhardt and the Legacy of Forced Labor,” beginning at page 339. Without wading too deep into the morass, Crowell offers a contextual reading of several key documents to support the revisionist position that “Aktion Reinhardt was about wealth seizure and SS control of Polish Jews, chiefly for labor purposes: It was not about mass murder.”

While Crowell’s analysis does not – indeed cannot – exclude the possibility that these sites were at some point devoted to the crudely mechanized destruction of human beings, including by mass gassing, I think he is persuasive in his interpretation of documents that render the scenario less likely than Cole asserts. For example, the authentic Franke-Gricksch inspection report (which wasn’t discovered until 2010 and is not mentioned by Cole) explicitly discusses the eastern program as a plunder operation, makes no reference to gassing, and includes population assessments that are plainly at odds with the numbers in the “final” Korherr report (which, it should be noted, has been disavowed by Korherr himself).

Crowell’s discussion of the top secret 1944 Globocnik report to Himmler along with its addendum also provides clear support for the interpretation that the AR system was primarily devoted to wealth seizure and includes an important note about “relocated persons” being given chits as a kind of bullshit assurance that “future compensation” would be rendered for their assets “some day in Brazil or in the Far East.” If the reference to “relocated persons” meant Jews – and there is a strong contextual reason to assume so, given the geographic presumption in the wording – then this addendum is difficult to reconcile with the notion that Jews were being systematically snuffed upon arrival at the camps.

While I make no apology for assigning Crowell plenipotentiary status in this arena, I realize it may be considered bad form since I am his publisher. Let this be my disclaimer, then, if such be warranted. I may be biased, but I am convinced that the importance of Crowell’s research has not been fully appreciated, and I think that his concise but granular study of extant documents hovering around the AR camp system are relevant and need to be considered along with the forensic and testimonial issues that revisionists will likely raise in counterpoint to Cole’s argument. In any case, when you grapple with informed disagreement, it is wise to seek out what philosophers of knowledge call “epistemic peers,” if only as a safeguard against the conceit of certitude, and I think the views of Crowell and Cole can be usefully considered as a proximate peerage; they’re intelligent men evaluating the same evidentiary chain, presumably in good faith, yet reaching different conclusions.

I should mention also that it is largely due to Crowell’s better known socio-cultural study of mass gassing claims that I am inclined to view particular gassing claims from a default perspective of skepticism. World War II mass-gassing stories are so bedeviled with conflation, confabulation, and culture-bound confusion – and for delineable reasons – that it is well, in the absence of clear-cut physical evidence, to weigh sociogenic explanations against the kind of literal interpretation that holds sway in the standard historiography.

Shadows and Mirrors

In forms of storytelling low and high, we have come to recognize a narrative device. By allusion to Dostoyevsky, it may be referred to as the Doppelgänger or the “Double.” It’s also sometimes called the “Shadow,” which I like better. I’m never sure about these things. I don’t know if it’s a modern invention or one of those Jungian archetypes that Joseph Campbell used to go on about. I’m not even sure whether it’s a trope or a motif, or some other lit-crit flavor I never learned. All I know is that it comes up often enough. Think of Humbert Humbert playing his cat-and-mouse game with Clare Quilty in Lolita, or think of the drug-addled narc in Phillip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly – itself a re-imagining of Nabokov’s The Eye – unwittingly stalking himself until the damage is done. Think of Marlow and Kurtz, or think of lycanthropic myths, or, if you’re a simpleton, stop at Jekyll and Hyde or – why not? – The Nutty Professor. Jerry Lewis version, please.

The Shadow may appear as a liberating demon like Tyler Durden in Fight Club, or as a beastly projection like Patrick Bateman in American Psycho. But the underlying psychology isn’t so moveable; it always settles around the problem of the divided self, and around such conflict as arises when one mask is dislodged to reveal the secret face that haunts or entices. And, to bastardize Robert Burns, when a Shadow meets a Shadow, there must come a reckoning.

It’s tempting to read David Cole’s unexpected and possibly important memoir as a kind of real-life Shadow story. The hallmarks are there. It’s about a guy haunted and lured by the former self he had hoped to bury, and the reckoning, obligatorily foreshadowed, comes as it must.

But if that’s the template, we are just as soon confounded by questions. Who is the Shadow? Is the Shadow David Cole, the once and again infamous “Jewish Holocaust denier” who left an indelible mark on one of the most abominated intellectual movements in modern history? Or is the Shadow David Stein, the titular “Republican Party Animal” who penned influential op-eds while organizing mixers for Hollywood’s “right-wing underground”? Is the Shadow flickering in the multiplicity of lesser pseudonyms and guises the author created as a matter of camouflage or whim as he stood in two circles? Or does the Shadow dwell elsewhere, perhaps in the hearts and minds of those who cast aspersions upon the man in subterfuge?

It’s a matter of perspective, I suppose. Or of sympathy. Or maybe it’s just a false start. Cole’s story is, in any case, ultimately not so much about a self-divided as it is about the burden of irrevocable choices and what cornered insight may be gained in the wake of so much preposterous tumult, when every cover is blown and there’s nowhere left to hide.

“I don’t want to be here,” Cole emphasizes at the beginning of his story. In the closing chapter, he plays on a recurrent Coen brothers theme to assert that he has “learned nothing.” I believe one of these voices. I am deeply suspicious of the other.

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 6(3) 2014

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a