Setback to the Struggle for Free Speech on Race in Australia

Part 1

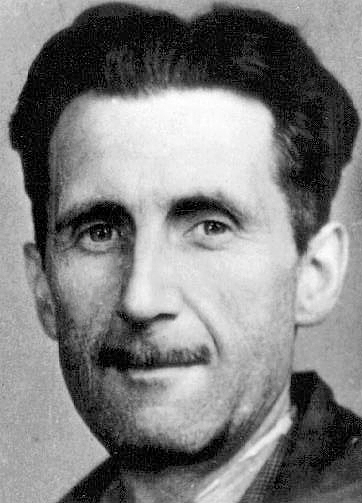

“I am well acquainted with all the arguments against freedom of thought and speech – the arguments which claim that it cannot exist, and the arguments which claim that it ought not to. I answer simply that they don’t convince me and that our civilization over a period of four hundred years has been founded on the opposite notion. […] If I had to choose a text to justify myself, I should choose the line from Milton: “By the known rules of ancient liberty.” The word “ancient” emphasizes the fact that intellectual freedom is a deep-rooted tradition without which our characteristic Western culture could only doubtfully exist. […] If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.” —George Orwell, Proposed but Unpublished Preface to Animal Farm[1]

I

For two years in Australia there has been an intense “culture war” between those thoughtful citizens who seek, in the name of the freedom of speech, reform of the Racial Discrimination Act and those others, some idealistic, who have opposed such reform on the grounds that it would lessen what they claim are needed protections for vulnerable persons against racial vilification and racial hatred. In August 2012, in an address to the Institute of Public Affairs, the then leader of the federal Opposition, Tony Abbott, inaugurated debate by promising that, if the Liberal-National coalition which he led were to be elected to office at the next elections, it would legislate a partial repeal of the Act. Twenty-four months later, now the Prime Minister, Abbott suddenly announced that no reform would take place after all. A battle for free speech has been lost. This is the story of that battle, which has lessons for freedom-lovers the world over.

II

The Racial Discrimination Act in its first form was a statute passed by the Australian Parliament during the Prime Ministership of Gough Whitlam, leader of the Australian Labor Party. Whitlam, whose party won the national elections in 1972 and 1974, introduced massive changes to the Australian political order which can broadly be summed up as internationalist rather than nationalist, left-wing rather than right-wing and socialist rather than liberal-conservative. As a result mainly of gross mismanagement, the Whitlam Government’s mandate was terminated by the Governor-General, Sir John Kerr, in November 1975 in lawful but controversial circumstances.

The Act was enabled by a questionable interpretation of the “external affairs” power contained in Section 51(xxix) of the Australian Constitution, an interpretation later upheld by the Australian High Court. The Act was legislated to conform to the authority of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, an article of the United Nations Organization.

Racial discrimination would occur under the Act when someone was treated less well than someone else in a similar situation because of his or her race, color, descent or national or ethnic origin. Racial discrimination could also be caught under the Act when a policy or rule appeared to treat everyone in the same way but actually had a deleterious effect on more people of a particular race, color, descent or national or ethnic origin than others.

It was henceforth against the law to racially discriminate against a person or persons in areas including employment, land, housing and accommodation, the provision of goods and services, and access to public places and facilities. The Act since then has been administered by the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, later renamed the Australian Human Rights Commission.

III

In 1994 the ALP Government led by Paul Keating announced that it intended to introduce a new bill styled the Racial Hatred Act to extend the coverage of the Act so that people could complain to the Commission about racially offensive or abusive behavior. Supporters of the change presented it as an attempt to “strike a balance” between the right to communicate freely and the right to live free from vilification. This proposal led to an intense national debate.

The proposed bill had been preceded by a draft bill in 1992, which itself depended upon three earlier government-initiated or -supported inquiries. In introducing the 1994 bill in the House of Representatives, the Attorney-General (Mr. Lavarch, the member for Dickson) referred to these: “Three major inquiries have found gaps in the protection provided by the Racial Discrimination Act. The National Inquiry into Racist Violence, the Australian Law Reform Commission Report into Multiculturalism and the Law, and the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody all argued in favor of an extension of Australia’s human rights regime to explicitly protect the victims of extreme racism.”[2]

The Opposition’s shadow attorney-general (Mr. Williams, member for Tangney) responded to this: “While these reports may have prompted a racial hatred bill, it is difficult to see how their recommendations are reflected in this bill. All three reports recommended against the creation of a criminal offense of incitement to racial hatred or hostility. This bill creates such an offense. [In the long run this did not become law.] The reports favored the creation of a civil offense of incitement to racial hatred where a high degree of serious conduct is involved. This bill establishes a civil offense with the significantly lower threshold of behavior which “offends, insults, humiliates or intimidates.” These words clearly include the hurt feelings which the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission rejected as the basis for a civil offense, concerned that such a low standard could lead to a large number of trivial complaints.”[3]

A more serious objection to the inquiries was mentioned by the man whose speech was, in my judgment, the best of all in the debate, that of Graham Campbell, ALP member for Kalgoorlie. Campbell, already a rebel within the parliamentary party’s ranks, would soon afterwards be forced out of the ALP. For some time after that he continued to hold his seat of Kalgoorlie as an Independent, while endeavoring unsuccessfully to launch a new political party named Australia First. Campbell said: “It is clear in the texts that there was networking between the authors of these reports. […] Only the report of Irene Moss [The National Inquiry into Racist Violence] supported criminal sanctions which were contained in the 1992 draft bill and are also contained in the 1994 bill. I would urge interested academics who still care about free speech to analyse this Moss report closely, because this document, which I believe to be intellectually corrupt, is the main justification for federal racial vilification legislation.”[4]

He may have been correct on at least two scores in his charge of intellectual corruption. That inquiry, which had been set up by an earlier ALP government, was placed in the hands of two representatives of minority ethnic groups who were thus interested parties and should never have been invested with such a task, nor should they have presumed to undertake it. Such an inquiry should have been in the hands of clearly impartial as well as qualified persons, and there should have been a majority of persons drawn from the majority British ethnic group, so that justice could be seen to be done as well as be done.

Secondly, it is plain from the text of the report that submissions made by individuals and groups holding views contrary to those of Ms Irene Moss (the Chinese wife of a Jew) and her assistant, Mr. Ron Castan QC (a Jew) were not fairly taken into account. This can be seen in the report’s refusal to adequately define the key terms “race” and “racism” and also in its scandalous mistreatment of the Australian League of Rights.

Mr. Campbell had further pertinent remarks to make:[5]

“In any consideration of the new Racial Hatred bill, the public consultations and the written public submissions on the 1992 draft bill should have been taken into account and the results, at the least, made public. I placed a question on notice about the bill and, among other things, asked about the results of the 1993 public consultations and submissions. The attorney-general took three months to answer and made it clear that he would not be making the results public. This was a typical display of arrogance.

A public submissions process was conducted, yet the public was not to be informed of the result. I strongly suspected that the reason for this was that the results were not what the attorney-general wanted to hear. And so it proved. Freedom-of-information documents revealed what I had expected. Written submissions ran almost seven to one against the bill and the attempt to stack the public consultations process had clearly failed. The attempt of the attorney-general to cover up the results is merely a measure of the misrepresentation, intellectual corruption and deceit which has marked the entire sorry history of the push for such legislation. […]

[…] the bulk of the media is quite happy to countenance a partisan like Irene Moss acting at one and the same time as advocate for supposed victims of racial intolerance and inquirer into such supposed intolerance. Not only that, but she was also to have administered the civil section of the legislation she called for, as her successor will do if the law before us is passed.

There is absolutely no understanding or appreciation of just how improper it is for the same person to be advocate, judge and jury in one. Those who rightly uphold the general principle of division of powers in our wider political context should be deeply concerned about the blurring of such responsibilities in quasi-judicial bodies like the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. […] This is the sort of new class law we are evolving – a de facto judicial system in which an accusation is taken as proof and the publicists are also the prosecutors and the judges. Not only that, but determinations of the commission can be registered in the Federal Court and become legally binding – a star chamber usurping the authority of a proper court.”

Campbell made other very serious criticisms of the Government’s handling of the 1992 draft bill:[6]

“[This bill] was supposed to lie on the table while people made submissions. A member of my staff asked the attorney-general’s office how people could obtain the bill and was told it could be obtained from government bookshops. He asked two people in two separate states to ring government bookshops and ask for the bill and no-one in either bookshop knew of the bill’s existence. He then wrote letters, published in The Age on 24 December and The Australian Financial Review on 31 December 1992, bringing attention to what was happening.

It was only at the very end of 1992 that the Attorney-General’s public affairs section was brought in to co-ordinate the selling of the bill to the media and to organize a public consultation process. There was no proper submission process in place until then. It was clearly an afterthought. Advertisements appeared in early January 1993 letting people know that a submission process on the bill would be conducted and offering to send people copies of the bill, the second reading speech and a fact sheet. The written submission process, however, was held over the holiday break when most people would be thinking about anything else but politics, or perhaps so it was hoped.

The Attorney-General’s Department also tried to fix the result of the travelling consultation process by holding meetings in venues of groups most likely to support the bill, such as ethnic affairs commissions and so on. It also sent out letters asking those organizations to mobilize their members – that is, likely supporters of the bill – to be at the meetings. The attempt to stack the meetings, however, seems to have been largely unsuccessful.“

Twenty-six members spoke after Campbell and effectively ignored his thesis, which leads to the strong presumption that it was correct.

Others, however, rebuked the Government for its handling of the preparations for and mode of presentation of the bill. Mrs. Sullivan (the member for Moncrieff) commented on “the unseemly haste with which this bill is being pushed through this chamber.”[7] Ms. Worth (the member for Adelaide) added:[8]

“The fact that the Coalition and the community have been given less than a week to discuss the [bill] is indicative of a government which has little regard left for the opinions of the wider community and the due process of the Parliament.”

Mr. Cobb (the member for Parkes) stated:[9]

“The previous speaker says that we have had plenty of time to look at it because we knew it was coming. Sure we knew it was coming, but we did not know which form it would take. […] The Australian people have also not been largely consulted on it.”

Several speakers from the Coalition argued strongly that there was no adequate evidence that the Australian people as a whole wanted any such bill. Mr. Nehl (the member for Cowper) reported:[10]

“It is interesting, too, that when the government first brought in its bill, in 1992, it had community consultations right around Australia. There were 646 submissions on the bill received from the public, and 563 were opposed to the legislation. There were only 83 in favor of it.”

Opposition speakers also claimed that the bill did not really have the support of ethnic minorities in the nation, it being seen as unnecessary and potentially divisive; Government speakers claimed otherwise.[11]

Overall, the unsatisfactory nature of the Government’s introduction of such legislation suggested that by subterfuge a piece of devious social engineering was being attempted. As Mr. Cadman (the member for Mitchell) said, it seemed that the ALP was “setting an agenda and a system of attitudes or values for Australia not sought out from the Australian people themselves.”[12]

IV

In the 1994 House of Representatives debate only five of the thirty-nine speakers tried specifically to define the key term “racism.” There were, however, implicit definitions in other speeches, as well as attempts to define associated terms such as “racial hatred” and “racial vilification.” Many speakers on both sides sought to distance themselves from racism. Two speakers warned about the misuse of such terms for ulterior and questionable purposes. Campbell said:[13]

“A racist today is anyone who wins an argument with a multiculturalist. […] On key issues such as immigration, multiculturalism and Asianization we have a tyranny of the minorities and a disenfranchisement of the majority. This bill is the starkest indicator of that process so far. The elites who have been pushing these policies realize that, even though they dominate the bureaucracies and academia, they are losing the intellectual argument. Their crude cries of ‘racist’ and ‘racism’ are proving less and less effective. Now they want a piece of legislation to complement the declining power of the social sanctions against speaking out.”

Mr. Cameron (the member for Stirling) said:[15]

“Under political correctness law, however, there is no accepted definition of what constitutes racial hatred. […] Some sections of the community, however, regard any statement against the perceived interests of a minority group as racist. For example, Tracker Tilmouth of the Central Land Council[14] reportedly claimed that the Greens and the Coalition were racist for daring to propose amendments to the land fund legislation. Those with extreme views are well represented in the race-guilt enforcement industry charged with responsibility for the civil side of the law.”

Source: By Branch of the National Union of Journalists (BNUJ). (http://www.netcharles.com/orwell/) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

“In State v Klapprott, the Supreme Court of New Jersey held that a statute that made it an offense to utter any statement inciting hatred, abuse, violence or hostility against a group by reason of race, color, religion or manner of worship, was void for uncertainty, because the terms ‘hatred’, ‘abuse’ and ‘hostility’ are abstract and indefinite.”

Mr. Filing (the member for Moore) noted:[17]

“The international instruments which form the constitutional support for this bill avoided reference to ‘incitement to racial hatred’, on the basis that ‘hatred’ is too subjective a term for a court to assess. In the USA and Canada, concern has also been expressed that the term is too uncertain a standard to include in penal legislation. […] Chief Justice Brogan concluded that it is not possible to say when ill will becomes hatred. He noted that there is no norm to say when such an emotion comes into being, and that it cannot be made a legitimate standard for a penal statute.”

Concern was also expressed by Opposition speakers about the vagueness used by the bill in its proposed amendment to provide for a civil prohibition (which in due course became the law). Mr. Ruddock (the member for Berowra) commented:[18]

“The Commonwealth standard of ‘insult’ and ‘offend’ is both broad and vague in our view in that an extraordinary range of statements are likely to be included under this definition.”

Mr. Nugent (the member for Aston) added:[19]

“The problem with using terms such as ‘offend’, ‘insult’ and ‘humiliate’ is that they are largely subjective in nature. The courts in the UK have had trouble interpreting the word ‘insult’ in relation to public order legislation, and there have been similar problems in the USA.”

Mr. Connolly (the member for Bradfield) complained:[20]

“No other jurisdiction in Australia has civil standards comparable to those in this bill […] where we find words such as ‘offend’, ‘insult’, ‘humiliate’ and ‘intimidate’ […] all words closely associated with value judgments.”

Oddly, the topic of race itself was almost totally ignored. It may be that the House collectively showed an ostrich-like attitude to the issue and indirectly encouraged a Lysenkoist attitude to the science of races. Traditional anthropology, before the changes and innovations most of all associated with Franz Boas (a Jew), did not accept the currently fashionable doctrine of racial equality. Some students of race still do not. William Gayley Simpson provided a profound consideration of the topic in his book Which Way Western Man?[21] He wrote, inter alia:

“A race is a major division of the human species. Its members, though differing from one another in many minor respects, are nevertheless, as a whole, distinguished by a particular combination of features, principally non-adaptive, which they have inherited from ancestors as alike as they are themselves. These distinguishing features are most apparent in body, where they are both structural and measurable, but manifest themselves also in ‘innate capacity for intellectual and emotional development’, temperament and character. With this we may compare Professor Bertil Lundman’s definition: ‘Race […] is a term that can be applied only to a reasonably homogeneous human group that has preserved its hereditary characteristics almost unchanged through a long succession of generations.’

What then is a ‘racist’? For all of forty years there has been acute need of honest and fearless inquiry about what race is, and an atmosphere of free discussion out of which might have come something like a scientific consensus as to whether or not racial differences are real and, if so, how much attention they require. But ‘racist’ is a term of opprobrium that was invented by the equalitarians to prevent such investigation and discussion.”

Simpson devoted four pages to listing thirty-three distinguished scientists who rejected the doctrine of racial equality. He provided details of each of them and of their careers.

An important short political study of the race question is Race and Reason by Carleton Putnam.[22] In the introduction by R. Ruggles Gates, Henry E. Garrett, R. Gayre of Gayre and Wesley C. George (four of the scientists listed by Simpson) these authorities made an important comment on the corruption of science by political ideology:[23]

“We can also confirm Putnam’s estimate of the extent to which non-scientific, ideological pressures have harassed scientists in the last thirty years, often resulting in the suppression or distortion of truth. […] we have no hesitation in placing on record our disapproval of what has been all too commonly a trend since 1930. We do not believe that there is anything to be drawn from the sciences in which we work which supports the view that all races of men, all types of men, or all ethnic groups are equal and alike, or likely to become equal or alike in anything approaching the foreseeable future. We believe on the contrary that there are vast areas of difference within mankind not only in physical appearance, but in such matters as adaptability to varying environments, and in deep psychological and emotional qualities, as well as in mental ability and capacity for development. We are of the opinion that in ignoring these depths of difference modern man and his political representatives are likely to find themselves in serious difficulties sooner or later.”

Putnam argued that wide-scale dishonesty characterized American discussion of racial controversies. Commenting on the Supreme Court desegregation decision of 17 May 1954, he had this to say about “the patent partiality of the authorities cited in favor of integration”:[24]

“The majority of these appear either to belong to Negro or other minority groups or to have prepared their studies under the auspices of such groups. To expect these groups to present impartial reports on the subject of racial discrimination is like expecting a saloon-keeper to prepare an impartial study of prohibition. […] Their point of view is important and deserves consideration. Many of them are brilliant and consecrated men. But to permit them to provide the overwhelming preponderance of the evidence is manifestly not justice.”

Putnam denied that there was virtual unanimity among scientists on the biological equality of the Negro with the other two major races:[25]

“There is a strong northern clique of equalitarian social anthropologists under the hypnosis of the Boas school which… has captured important chairs in many leading northern and western universities. This clique, aided by equalitarians in government, the press, entertainment, and other fields, has dominated public opinion in these areas and has made it almost impossible for those who disagree with it to hold jobs. […] The non-equalitarian scientists have been forced largely into the universities of the South where they are biding their time.

It is folly to talk of freedom, either of the press or of any other kind, when such a situation exists. […There is] a trilogy of conspiracy, fraud and intimidation: conspiracy to gain control of important citadels of learning and news dissemination, fraud in the teaching of false racial doctrines, and intimidation in suppressing those who would preach truth.”

Particularly germane to the present Australian situation is Putnam’s analysis of political opportunism as a corrupting factor in party politics involving discussion of racial issues. Leaders of both major political parties in the USA, he said, close their eyes to the truths of race:[26]

“Partly [it is] through ignorance of its scientific validity. But this ignorance they are inclined to cherish, and to avoid correcting, because of the balance of power held by Negro voters in certain key states. […] The tragedy is that the great majority of Americans are dividing their votes on other issues in such a way as to give this issue into the hands of the minority. […] Could the race question be isolated so that it could first be thoroughly debated and then voted on by itself alone, the minority would be swamped.”

In a subsequent book, Race and Reality,[27] Putnam pointed out that racial discrimination is sometimes both scientifically and ethically justifiable (in answer to the question: “Isn’t it unfair to discriminate legally against the exceptional Negro on the basis of a racial average?”):[28]

“We discriminate legally against exceptional minors by not allowing them to vote, though certain of them may be more intelligent than many adults. Discriminations of this sort are necessary to the practical administration of human affairs. […] the Christian religion offers salvation to all true believers, but this has nothing to do with status. Status has to be earned, in religion as elsewhere, by merit. […] Christ was a man of infinite compassion, but he was not a man of maudlin or undiscriminating sentimentality. Christ’s life, among other things, might well be called a study in firm discrimination.”

Putnam supported the age-old love of kith and kin, “the natural impulse of men to group themselves around their own kind.”[29] He also stressed the importance of racial discrimination in those contexts where races must be considered as wholes, as opposed to contexts involving individuals of races:[30]

“But there is nothing unchristian in facing the fact that, as individuals differ in merit, so averages differ among races in those attributes involving specific cultures. […] when we are confronted with a situation where a race must be considered as a race, there is no alternative to building the system around the average. The minor handicap to the exceptional individual, if such there be, is negligible compared to the damage that would otherwise result to society as a whole.”

Putnam defended the importance of the traditional meaning of the word “discrimination”:[31]

“Is that man unjustified who marks a difference between right and wrong, between better and worse? It has become the vogue to condemn discrimination without asking what the reasons for the discrimination may be.”

One of the greatest intellects of last century, the metaphysician and writer on sacred traditions, Frithjof Schuon, stressed the importance of true discourse on race:[32]

“Race is a form. […] It is not possible, however, to hold that race is something devoid of meaning apart from physical characteristics, for, if it be true that formal constraints have nothing absolute about them, forms must none the less have their own sufficient reason; […] races […] must […] correspond to human differences of another order. […]

In order to understand the meaning of races one must first of all realize that they are derived from fundamental aspects of humanity and not from something fortuitous in nature. If racialism is something to be rejected, so is an anti-racialism which errs in the opposite direction by attributing racial difference to merely accidental causes and seeks to whittle away these differences by talking about inter-racial blood-groups, or in other words by mixing up things situated on different levels. […] Racial mixtures may be good or detrimental according to the case.”

An important recent study of the impact of ideology upon anthropological science can be found in Kevin MacDonald’s The Culture of Critique.[33] In a chapter on “The Boasian School of Anthropology and the Decline of Darwinism in the Social Sciences,” MacDonald concluded:[34]

“A common thread of this chapter has been that scientific skepticism and what one might term ‘scientific obscurantism’ have been useful tools in combating scientific theories one dislikes for deeper reasons.”

Ideological interference with the Australian political order in matters of race most of all was manifest some three decades earlier. Mr. Filing (the member for Moore) referred to the influx of Asians into the nation:[35]

“It was Harold Holt’s Coalition government in March 1966 that abolished once and for all the White Australia policy – a decision which enabled the welcome inflow of so many people from such a wide range of ethnic and racial backgrounds, and since then including people from Asian nations particularly, especially China and Vietnam.”

Former Prime Minister Bob Hawke (ALP) eventually admitted publicly that the termination of this policy had been brought about by a semi-secret agreement between the Coalition and the ALP, with the Australian people themselves not being asked in advance for a mandate for such momentous change through a referendum, since it was considered likely that they would vote No. This is one of the most significant historical developments in Australian affairs to call in question the nation’s habitual self-description as a “representative democracy.”

In this context, the enthusiasm of several speakers for “education against racism”[36] sounded most suspect. It seemed that members from both political sides were equally eager to see in place a program that would constitute indoctrination into the ideology of racial equality rather than an academic inquiry into the nature of racial and ethnic differences and different ways of addressing these within nations.

V

The argument over whether or not the proposed bill was a justifiable limitation of free speech was, in my view, clearly won by its opponents. In introducing it the attorney-general, Mr. Lavarch, asserted that in it “free speech has been balanced against the rights of Australians to live free of fear and racial harassment.”[37] This smooth argument had for some years been advanced, notably, by Jewish spokespeople in the press and seems to have been devised to try to get over the otherwise embarrassing obstacle of the fervor with which British nations have traditionally defended free speech. The argument assumes that such a balance is necessary (false) and that the two goods being balanced are of equal worth (false). Implicit is the assumption that we cannot have a national climate reasonably free for all citizens from fear and from racial harassment and also have freedom of speech (false). In short, the argument is worthless casuistry.

Government speakers often pointed out that, as Mr. Tanner (the member for Melbourne) said, “freedom of speech is not an absolute”. Many examples were given of laws that already qualified what could be legally expressed. These related to a wide range of subject matter, including (1) defamation and libel; (2) copyright; (3) obscenity, child pornography and censorship; (4) official secrecy, national security, the state and federal Crimes Acts; (5) contempt of court; (6) contempt of Parliament, rules for Parliamentary speakers that forbid attacks on the Royal Family or the financial probity of fellow members, the Parliamentary Privileges Act, the Public Order (Protection of Persons and Property Act of 1971) which enables protesters in the gallery to be dealt with, and penalties applying to people who display posters in the gallery; (7) consumer protection, the Trade Practices Act which imposes restrictions in order to ensure that business activity is conducted fairly and honestly, false advertising law, and fraud laws; (8) broadcasting regulations; and (9) criminal laws about the counselling of others to commit a crime. None of these constituted the same degree of erosion of free speech that the bill did, for it broke new ground in striking at the freedom of each citizen to publicly make basic political comment and criticisms concerning major issues of national policy and direction.

Many important concerns were raised by the Coalition speakers. Mr. Ruddock (the member for Berowra) said:[38]

“Our consultations have revealed that some people do have grave reservations about the fact that people can be jailed for what they say as distinct from what they do. […] We do not think that a government should ever introduce or endorse legislation which will send people to jail for offenses that are not clearly defined in practical terms.”

Mr. Filing (the member for Moore) enlarged on the Opposition’s objections to the proposed Section 60 (an amendment to the Crimes Act of 1914):

“There is a fundamental difference […] between expressing an opinion, however odious, and threatening violence to personal property. […] We on this side of the chamber will not support a criminal sanction for expressing a view and encouraging others to adopt it when you are not inciting people to damage property or persons.”[39]

Mr. Forrest (the member for Mallee) commented:[40]

“I have got some concerns about how this bill basically neuters what I consider to be the reasonable expectation which all Australians have come to treasure – the right to free speech. That right preserves the capacity for people to speak out on a whole range of issues which they consider to be in the public interest. Sometimes these views may require comment in regard to ethnic origins, whether in respect of immigration, foreign policy or any other matter. I see legislation such as this, in the hands of fringe minority groups, being used to constrain such freedom. […] Although the deliberate giving of offense may not be the purpose of such speech, it is sometimes amazing what people can be offended by.”

Mr. Cameron (the member for Stirling) pointed to another serious implication of the bill:[41]

“All laws restricting speech contain a penumbra, a twilight zone in which a person cannot be sure if his statements infringe the law, and therefore cause the prudent and the timid to refrain from making a much wider range of statements than the law intended to prohibit. Sanctions imposed by the courts will probably not be the major practical impediments to free speech.

Those who control access to the forums for disseminating ideas – the publishing houses, the media and academia – will be forced to walk on egg shells when dealing with any issue touching on race. They will, most perhaps from a genuine desire to act lawfully – but some from a cynical desire to suppress debate – cite the law as a reason not to publish anything at variance with contemporary wisdom on multiculturalism.”

Mr. Slipper (the member for Fisher) noted: “By attempting to silence our opponents, we question our own commitment to the cause and acknowledge the strength of our opponent’s position. […] We should all be concerned with a state which seeks to regulate opinions and which declares the truth and then seeks to suppress any deviation. […] The thought police are to be let loose. This government will be setting up a type of offense which will see political prisoners created in Australia.”[42]

Government speakers clearly failed to rebut the free speech argument. Mr. Latham (the member for Werriwa) tried to set up an alternative ideal of “fair speech, consistent with tolerance and understanding.”[43] This ignores the fact that people have varying degrees of understanding, different ideas of what should be tolerated and different ideas about what is or is not fair speech. Ms. Henzell (the member for Capricornia) did not want the law “to permit disadvantaged or vulnerable groups to be seriously harmed by more powerful groups.”[44] However, the bill’s supporters as a group failed completely to produce evidence of such “serious harm” to ethnic minorities within Australia on a sizeable scale. Mr. Theophanous (the member for Calwell) stated that “there are limits to utterances when they promote racial hatred and undermine multicultural society.”[45] This ignored the fact that many Australians might want to argue in favor of a homogeneous, if not monocultural society, and that such a position in no way automatically indicates that they are racial haters. Later this speaker made a most significant interjection:[46]

“It is to stop Nazis and others in Australia of their type that this bill has been organized!”

He may inadvertently have pointed to a secret agenda behind the bill designed in the interests of one particular ethnic minority –Jews. Mrs. Easson (the member for Lowe) said:[47]

“This bill […] attacks the public tolerance of racist speech. If we declare our intolerance of racist speech, the social ethos will evolve over time away from racism.”

This smacks more of social engineering than assistance of vulnerable persons. And Mr. Hollis (the member for Throsby) saw the bill as rejecting “the right of racists to go out and practice their craft”.[48] For him, perhaps, “racists” were any people who disagreed with himself on issues involving race. To sum up, the Government speakers were bent on censorship, proud of their moral virtue and unwilling or unable to countenance the existence of, and the expression of, a plurality of views on matters involving race – or the possibility that their own views might be to some extent erroneous.

VI

A feature of the 1994 debate was the apparently complete obsequiousness of the Australian Parliament to the United Nations Organization. A number of speakers cited the UNO as having provided the constitutional basis for national legislation on racial issues.[49] Ms. Worth (the member for Adelaide) quoted the preamble to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination as stating: “…any doctrine of superiority based on racial differentiation is scientifically false, morally condemnable, socially unjust and dangerous and. […] there is no justification for racial discrimination.”[50] There is a dangerous odor of institutional infallibility about that article. It is also regrettable that it repudiates ‘racial discrimination’ tout court when, properly, it should only repudiate ‘unjust racial discrimination’. Such carelessness with terminology (or is it intended manipulation?) does not encourage confidence in the UNO. Putnam exposed the unscientific nature of a UNESCO Statement on Race published in 1950.[51] UNESCO was forced to first publish a modification and later a booklet rebutting both the initial statement and the modification by fourteen scientists of world standing. Putnam went on to show how the scientists’ correction was later ignored by the big battalions of media, politicians, the entertainment industry, scientific hierarchy and educational establishment.

Not one speaker in the debate was prepared to address the unreliability, if not outright mendacity, of the UNO, or to discuss whether it really was in Australia’s interest to be bound by any of its declarations – or to what extent Australia should co-operate with it. The UNO has been the subject of unfavorable scrutiny in a number of important books.[52] One of the great questions of our time is whether or not the UNO was deliberately established as the prototype of a future world government, the “New World Order,” which in fact would be a global tyranny of certain elite groups. Ms. Worth also referred to “the standards that the global community has agreed upon”; but it is doubtful that any such community can truly be said to exist, let alone that it was properly consulted, with every adult person in every member state being well informed about the standards beforehand.

VII

One explanation for the appearance of the 1994 Racial Hatred bill is that it formed part of a program to transform Australia from its original status as an essentially British nation into… something else. The key word used to describe that something else is one with a sliding range of possible meanings that easily enables deception and causes confusion. That word is multiculturalism. It is possible to make the idea of a ‘multicultural Australia’ sound rich and exciting, an example of the truth that variety is the spice of life. On the other hand, perhaps such an Australia might be easily made into a satrapy of the New World Order, in which a demoralized citizenry of quasi-slaves have no peoplehood left, no folk or kin group to protect them from the tyrants. Understandably, proponents of multiculturalism tend to be in favor of plenty of immigration and from as many different ethnic groups around the world as possible. This raises the question of whether the bill was seen partly as a means of inhibiting public expression of opposition to high levels of immigration and to multiculturalism.

Mr. Robert Brown (the member for Charlton) had this to say:[53]

“I believe that in Australia we have developed and refined an important concept when we talk about a multicultural society. In the process of doing that, we have, in effect, adopted a positive and practical policy of national purpose and identity. […]

We have a society which consists, quite deliberately, of people from varied and diverse ethnic, racial and cultural backgrounds. […] we have developed a country which has a great number of stimulating, exciting, diverse and interesting qualities. […]

I think it is one of the greatest social and inter-racial initiatives ever undertaken anywhere in the world. I believe that it represents a deliberate attempt to bring together people of diverse cultural and racial backgrounds on the basis of their simply being people. […]

There can be little doubt that the vibrant culture that exists in Australia today is a welcome replacement of the narrow xenophobic Australia of the past. […] we are a more successful, energetic, thoughtful, forward-looking and outward-looking society than we ever were in the past.”

What identity? What qualities? What does “simply being people” mean? The speech is vague; the language turgid; it looks like politicians’ cant. Notably, it involves slander of the past (the times of the pioneers, the explorers and the soldiers in two great wars) in order to flatter the present.

Mr. Latham (the member for Werriwa) remarked:[54]

“This is indeed landmark legislation. It represents an important landmark in Australia’s transformation from an inward-looking, monocultural society to an outward-looking, tolerant, confident, multicultural society.”

Was the British Australia of the recent past, which saw itself as part of a noble and magnificent empire of many peoples, “inward-looking”? It does not seem to have occurred to the speaker that unity of culture, based upon unity of race, may also mean strength and profundity of culture, while multiculturalism, like syncretism in religion, may mean disintegration and decadence. And how tolerant is this new society to be of those who criticize it? Not very, the bill suggested.

Putnam issued in 1961 a warning of the dangers of undiscriminating immigration policy:[55]

“The immigration of many millions of people into the USA, particularly during the past eighty years, has brought together here the greatest assortment of ethnic stocks in the world and probably in history. If the lessons of European experience have any meaning, such a conglomeration of racial and ethnic elements renders a serious cultural decline inevitable. Symptoms of the decline are already apparent in the deteriorating state of some aspects of our culture, in the irresoluteness and confusion of our national leaders and in the virulence of frank anti-social behavior among our people far in excess of that encountered in West European countries, Canada and Australia. […] Today, in excessive homicide, treason, juvenile delinquency and other crimes with their tremendous cost in suffering and treasure, we are paying the price for our reckless generosity to peoples of other lands.”

Mr. Campbell (the member for Kalgoorlie) hit one nail right on the head:[56]

“This bill […] is clearly designed to stifle open debate on matters such as immigration and multiculturalism at a time when both are increasingly coming into public disrepute.”

And two Coalition speakers pointed to anomalies in the bill. Mr. Cameron (the member for Stirling) supported the concept of “racially blind” legislation:[57]

“This bill is analogous to the government prohibiting theft from migrants only. One wonders why the Government is extending a protection which all Australians should enjoy only to members of minority racial groups. The obvious, if cynical, answer is that the Government will not earn kudos from the multicultural lobby by passing a law with a general operation. The rest of us are entitled to feel discriminated against.”

Mr. Atkinson (the member for Isaacs) added:[58]

“To me, of fundamental importance to this country is one set of laws for a group of people who choose to live in this country and call Australia home. […] If we are going to bring people together in this country and develop an interest as Australians for Australians, we should not introduce legislation that enables racial qualifications to be placed in front of them.”

VIII

The most important political pressure group in Australia to consistently challenge the doctrine of racial equality has been the Australian League of Rights. This organization, founded in 1960, grew out of the Social Credit movement of the 1930s. It has always supported the Christian and British ethos of the nation, it has tended to be wary of programs for Aboriginal “advancement” and “land rights” (seeing these as potentially divisive of the political order), it has tended to oppose non-European immigration and favor the maximum possible ties with Britain and the former British dominions of Canada and New Zealand, it has favored patriotic nationalism and been very wary of the UNO, and it has often been critical of Jewish influence within national and international politics (which it has seen as often hostile to its own ideals and policies). It has been easy for its political opponents to stigmatize it as “racist” and “anti-Semitic.”

An important feature of the 1994 debate was what may be called the slanderfest of the “extreme right”, with the League as main target. For example, National Party Leader Tim Fischer (the member for Farrer) proudly stated:[59]

“Members of this house will know that over the years I have been involved in many battles against what we call the Far Right, the League of Rights and other organizations from the extreme Right, some members of whom hold the sort of odious racist views that this bill is intended to address. From that experience, I have come to know that these people do not think rationally about such issues. They interpret the actions of others, governments in particular, in terms of the twisted international conspiracies they imagine.”

Some might well see this sort of vague language as reckless vilification. Fischer went on to add:[60]

“In this respect, as in my constant and unflinching opposition to the Far Right, my record stands me in good stead and provides a self-evident defense against those who would seek to place the racist tag on my back or on the back of any member of the parliamentary National Party.”

Government spokesman Mr. Latham (the member for Werriwa) had this to say:[61]

“Yet a small minority of racists and racist organizations do express and seek to incite racial intolerance and hatred. […] We do have the League of Rights and we do have in election campaigns organizations such as Australians Against Further Immigration, which run their campaigns on a racist platform.”

An impartial analysis of both the named groups might also find evidence of unjust vilification here too.

Mr. Snow (the member for Eden-Monaro) said:[62]

“There is plenty of intolerance and bigotry about. For instance, the League of Rights has been mentioned in this debate. The League of Rights has a phobia about Zionism. […] Zionism poses some ethereal threat, which I have never been able to perceive in spite of all the writings of those who are on the right, such as those in the League of Rights.”

That was not an intellectually substantial rebuttal of the League’s commentaries on Zionist and Jewish influence in politics. It was vilification offered in defense of an anti-vilification bill!

At least seven other speakers participated in the slanderfest.[63] Not a single speaker in the whole debate sought to stem this avalanche of misinformation and defamation. A significant body of Australians was being demonized, leading to the strong presumption that the discussion was not the completely free exchange of views it might seem to be. What power within the political order could be so powerful that it was able to frighten both major political parties into such a dishonorable group attack?

IX

It seems that Jewish influence played a large part in the formulation of the Racial Hatred bill of 1994. That is, if Graham Campbell is correct in claims made in his speech. Campbell said:[64]

“Mr. Keating finally announced that the bill would definitely be introduced before the end of 1994 at the 36th biennial conference of the Zionist Federation of Australia. The outgoing president of the ZFA, Mark Leibler, was one of those who had most strongly pushed for this bill, with criminal sanctions. The choice of venue for the announcement underlined from where the major lobbying pressure for the introduction of such a bill had come. Of course, other ethnic groups and academics have been involved and Aboriginals have been used as a stalking horse, but the main driving force has clearly been the Zionist lobby.”

Mr. Campbell gave other examples of Jewish influence in Australia’s national politics: (1) At the same conference Mr. Keating announced the formation of a multicultural advisory council to advise the Government on cultural diversity dimensions of the centenary of Federation and the Olympic Games – and nominated as first (and at that stage only) member a lobbyist from the ZFA; (2) The imposition on Australia in 1988 of a “costly and counter-productive war-crimes trials process” [purely set up to catch alleged Nazis]; (3) The sacking of the secretary and deputy-secretary to the Immigration Department in 1990 because they resisted opening up a separate immigration category for Soviet Jews; and (4) The achievement of changes to the immigration rules which “were used to block controversial historian David Irving from entering Australia.”

In dealing with the attempt by Jewish spokesman Jeremy Jones to deny the truth of the third of these charges (which had been exposed in the Canberra Times by journalist Verona Burgess), Campbell said:[65]

“Neither the Zionist lobby nor anyone else has the right to use state authority to deny inconvenient facts of history and remain unchallenged. Nor should we attempt to suppress people who make such denials. […] This is how we should approach those who deny the Holocaust. They should be met with the facts and arguments in open debate and not suppressed. […] This bill is also designed to entrench one view of history as holy writ. All aspects of history, no matter how horrible and distressing to some people, should be open for critical examination and discussion. We cannot rule a line on the study of the past. I really believe that if we do not make a stand on this bill, then the authoritarian excesses will get worse.”

Campbell raised these matters with an admirable mixture of directness and tact:[66]

“I want to make it clear that in talking of the Zionist lobby, I am not talking about the great majority of Jews, many of whom, I know, are totally opposed to this bill. I am talking about a relatively small group in the Jewish community, disproportionately composed of authoritarian zealots who have crushed or silenced internal opposition. Due to a combination of money, position, relentless lobbying and the manipulation of their victim status, they have a very powerful influence, both in Australia and abroad.”

Although many other speakers referred to Jewish matters, most being sympathetic to Jewish interests,[67] none of the twenty-six who followed Campbell made any significant reference to his comments about the role of the Zionist lobby in promoting the bill and otherwise strongly influencing Australian political affairs. The natural presumption is that they knew they could not refute his thesis but did not wish to be associated with it.

X

After being passed in the House of Representatives (the lower house of the Australian Parliament) on party lines 71-59 the bill was sent for consideration to the Australian Senate (the upper house), which arranged for its joint (all-party) Legal and Constitutional Committee to investigate it. As a result some public hearings were heard and I attended the one in Melbourne on 24th February 1995, having arranged in advance to be allowed to make a submission. What occurred there, I believe, casts considerable light on the nature of both the bill and its eventual acceptance by the Senate (after which in amended form it became law as part of the Racial Discrimination Act). After being invited to address the hearing by its chairman, ALP Senator Barney Cooney, I began by explaining that I appeared as a private citizen and representative of a long line of British and European writers who had defended free speech. I continued as follows:[69]

“Within the last 24 hours, I have nearly completed a first reading of the transcript of the hearing held by this committee in Canberra a week ago on 17th February. This convinces me that there is still widespread confusion and error in many people about the nature of this bill and its implications. I remain convinced that the bill should be completely rejected at this stage, and that a new inquiry should be set up into relevant matters of society and race in this nation, an inquiry which is indisputably and manifestly impartial.

On page 276 of that transcript, we read that Senator Abetz said a week ago: ‘Let us say I was an outrageous revisionist of the academic view and said, ‘The Holocaust did not exist, did not happen.’ There are some people with that strange view of history.’ He indicated that he believed that such a view and the promotion thereof ‘would offend all Jewish people’ and would be done ‘because of the race.’ He added that ‘these revisionists say these things’ because they believe that ‘the Jews have perpetrated a fraud on society and got them to accept a version of history that was not true.’ Dr Sernack commented: ‘You may very well hold those beliefs in good faith but, nevertheless, it may not be reasonable in the circumstances to promulgate them.’ On page 280, Senator Abetz talked about a neo-Nazi and asked: ‘If there were a neo-Nazi meeting to which only neo-Nazis were invited to hear some revisionist history, would that be a public place?’

Later he referred to ‘this outrageous revisionist version of history’. Later still he referred to the revisionist view of the Holocaust as ‘just diatribe.’ These and many other references throughout the transcript show that an inadequate background of knowledge is being brought to the public deliberations on this bill and that a crudeness and lack of subtlety of terminology are being employed, which means clearly that the nation is not yet ready to have legislation on such controversial matters of race and society framed, debated, legislated and enacted. A Miss Chung said, on page 302, ‘We can never wait for the perfect time.’ However, the present time, the present context, is grossly imperfect, so the voice of wisdom says, ‘Not yet, not yet.’

I end with a series of challenging assertions which I am prepared to defend to the best of my ability. The bill is too vaguely worded and offers insufficient safeguards for intellectual freedom. The terms ‘racist’ and ‘racism’ are too vague for adequate debate. They are unscientific in the sense used by Professor Eric Voegelin of the term ‘fascism’ in his seminal work, The New Science of Politics, published by the University of Chicago Press in 1952 in America.[68] ‘Denial of the Holocaust’ and allied terms are prejudicial and seriously misleading. Revisionist historians, David Irving and the Australian League of Rights, as well as many other individuals and groups in the so-called far right spectrum, are honourable and decent people who deserve a fair hearing. Their exclusion from public debate on this bill by the major media is a national intellectual scandal. The member for Kalgoorlie in the House of Representatives, Mr Graeme Campbell, was correct to state that the major impetus for this bill has come from Jewish Zionist pressure groups and individuals, as he said in the House debate of 15th and 16th November. Jewish Zionist influence on our national politics has become excessive and needs to be curbed.”

The chairman in response suggested that there was no problem “under this bill in saying that the Holocaust did not occur” and likened such a claim to stating that Dresden was not bombed in World War Two, that the Kokoda Trail did not exist, that there was no Burma Railway built by the Japanese with prisoner of war labor, or that William III was a homosexual [that is, a series of obvious absurdities]. In response I said:[71]

“I think that is arguable. In any case, this bill needs to be seen in a context that goes far beyond that of Australia; a context that includes a number of other countries that have been mentioned in debate on this matter, such as Britain, France, Germany, Austria, Canada, America, where it is quite plain that there is what appears to be a worldwide campaign to inhibit as much as possible the expression of certain controversial views on various topics associated with race, of which the Holocaust and the degree of Jewish influence in national and international politics is one.”

The chairman asked why I picked out the Holocaust. I replied:

“Mr. Chairman, I am a writer. I believe it is necessary, as [Joseph] Brodsky, one of the Nobel Prize winners for literature, said, to speak the whole truth fearlessly. It is necessary to go to the heart of the matter. This I believe is where the heart of the matter is. Moreover, when I look at the transcript of last week’s hearing, I see that there is quite a significant number of references to Jewish matters, to Nazism, neo-Nazism, the Holocaust and so on. This is a very important aspect of this bill.”

The chairman repeated his question, and I replied:

“Because I think this takes us straight to the heart of the socio-political context in which this bill has been presented to the parliament. I have referred to the writings of Ian Dallas. I have one of his books here – a magnificent piece of writing called The Ten Symphonies of Gorka Konig.[70] He is a Muslim sheikh. He is a man of an extraordinary range of knowledge and intellect, and he would argue that I am doing just that, that I am going to the heart of the matter. The other matters you refer to may be important but they are not as important as the one I am referring to.”

There now occurred an extraordinary intervention. It so happened that in this small room, containing some fifteen or so persons, one of them was none other than Mark Leibler, the very powerful and prominent Jewish activist and leader to whom Graeme Campbell had referred in his House of Representatives speech. Leibler now passionately intervened:[72]

“Mr. Chairman, this is a new experience for me. I have never been before a Senate committee and listened to something which is really straight out of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Now that we are here, perhaps Mr. Jackson ought to be asked to explain. What he is obviously telling us is that all the ills of the world are attributable back to the Jews, that this is a worldwide conspiracy and the Jewish people are responsible for everything. I think it would be of interest to the committee if perhaps you asked Mr. Jackson to explain how all this happens, for example, how the Jews control the government here, how the Jews control the international community. Maybe you should invite him to explain.”

Rather taken aback by this onslaught and its intellectual crudity, I had the feeling that Leibler was acting a role, a familiar role for him, in which a person or a group or a view was not to be so much discussed as rubbished and hissed off the stage.

He and the chairman for a few moments discussed implications of Holocaust denial and its relationship to the bill. Leibler likened such “denial” to saying “that the moon does not exist or the sun or the earth is square.”[73] He then renewed his attack on me:

“But Mr. Chairman, we have been treated here to something which I have never heard but I have seen on TV. This is The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. This gentleman is talking about a worldwide Jewish conspiracy controlling all governments, controlling the world. I would like to know how this is done. He should be asked to explain.”

Fortunately, I was able to respond to these diatribes and the whole conversation is on the public record. I replied:[74]

“It should be quite plain, Mr. Chairman, that Mr. Leibler has grossly misrepresented what I said and given a superb example of what I was talking about when I talked about inadequate terminology and an inadequate background knowledge. I said nothing whatever about the Jews being responsible for ‘all the ills of the world.’ I have not talked about a conspiracy engineered by the Jews. To suggest that reality of the sun and the moon is comparable to the reality of a controversial historical event is nonsense. I resent very strongly the imputations that this gentleman has made about me.”

Leibler was plainly on the back foot now, as he had clearly ascribed to me views I had neither directly nor indirectly expressed, exaggerated statements I had made, and come up with a ludicrously stupid comparison. Leibler meanwhile continued in a very sarcastic voice:[75]

“I got it wrong, Mr. Chairman. It was not the Jews; it was the Zionists. Correct?”

It evidently did not occur to him that an apology was in order.

There now occurred another memorable exchange. The Chairman turned to a Mr. Pearce, a representative of the prestigious Victorian Council for Civil Liberties, and asked him:

“Mr. Pearce, what do you say about that? Do you agree with what Mr. Jackson said?”

Pearce replied:[76]

It amazed and disappointed me that this man said nothing in support of my free speech position and nothing about the way in which Leibler had clearly misrepresented me. I had the conviction that foremost in his mind was the desire not to be associated in any way at all with what he regarded as “anti-Semitism.” And, if I am correct, that shows the degree to which a taboo has infected Australian society: an eleventh commandment – “Say no ill of the Jews.” Pearce went on to argue, effectively I thought, that Holocaust denial would become illegal if the bill was passed. Along the way he remarked:[77]

“We are here to talk about this bill and not the international Zionist controversy.”

I managed to get another important point made:[78]

“No distinction has been made yet between the phrase ‘denial of the Holocaust’ and between revisionist historians of responsible and intellectual caliber who are not ‘denying the Holocaust’ but who are arguing that it has been exaggerated – something which any historian should be perfectly free to say about any particular historical event. Using the phrase ‘denial of the Holocaust’ constantly evades facing up to this question that it is not a matter of denial. It is a matter of questioning the extent of.”

Soon the chairman was again comparing Holocaust denial to saying that no Australian troops were killed on the Burma Railway, and I was able to make an important point about that:[79]

“I am not aware of any significant body of historians of academic and intellectual quality who are making any denials about the Australian activities in the Burma railroad et cetera and, therefore I am afraid that comparison is quite irrelevant. But there is such a body making these sorts of comments about the Holocaust. Some of them are in jail in certain countries and I feel that this legislation is at least a step in the direction of putting Australian intellectuals who are dissidents in gaol.”

Mr. Leibler soon remarked:[80]

“I could not really take this seriously. It is best that I say no more. I would hope that no-one else takes it any more seriously than I do.”

I thought his tone petulant; and it occurred to me that he was used to saying publicly the sort of defamatory things he had been saying about me without being effectively challenged. The major media often published Jewish attacks on their opponents but rarely if ever opinion articles by writers of “the extreme right”. But now, all of a sudden, he had a capable debating opponent from that stable who was being given opportunity to reply to him – and it was all going onto the public record. It seemed that he had grasped that he had better not take the debate with me any further.

A representative from the Australian Civil Liberties Union[81], Mr. Geoff Muirden, now uttered a word of support for me:[82]

“I feel that matters raised by the revisionists should be a matter of open debate. If the Jews take exception to it, as they apparently do, they should be able to meet the revisionists in open debate. There should not be this attempt to suppress David Irving from entering Australia.”

The conversation moved to the topic of combating racism by means of educational programs and, after several speakers had given their views, I was able to speak:

“We tend to assume in public discussions in this country and in other Western countries that education is a great good. It is surprising, however, how much written material by top quality minds now exists to suggest that modern mass education has in many respects been a very harmful influence. I can quote simply one top writer, Frithjof Schuon, one of the Perennialists School. He is a Muslim writer but he has argued this in quite a number of essays.[83] I have been listening with interest to what has been said in the later part of this discussion and it convinces me that the education first needs to begin among the people in this room and others who speak the kind of language that they speak. For I say again that if you use words like ‘racist’ and ‘racism’ you are using unscientific terminology, as Professor Voegelin said.”

In response to this, Leibler sneered: “Mein Kampf.”[84] He had been reduced to the schoolboy tactic of mindless derision. What on earth had my speech to do with Hitler?! I responded:

“Despite Mr. Leibler’s recent sneering comment, this is a serious matter, as I say. The word ‘racism’ needs to be very carefully examined; it will be found that it is used in many contexts with many ranges of meanings.”

The chairman tried to sweep aside my insistence on careful defining.[85] I replied:[86]

“Still coming back to your question relating to racial hatred, incitement to it and so forth, can we afford as a nation to frame and pass in the parliament legislation that flies too much in the face of truth? I think that is a question that has not been adequately answered at all today. I agree with what Mr. Wakim has said in his colloquial language – if I may put it that way – that a hell of a lot of work has to be done in order to reverse stereotypes. I have been observing that just today, because although I have made a number of points which have certainly not been answered by anyone here, people have gone merrily along their way using the old stereotypes that I have queried.”

The chairman tried to get Mr. Pearce to agree that legislation against racism is necessary in a multicultural society; but Pearce would not be drawn:[87]

“We do not see that the conduct which this bill will proscribe threatens social or public order. […] That is because there is no evidence that we have seen that the conduct which this legislation seeks to proscribe does threaten public and social order.”

He was supported by Liberal Party Senator O’Chee:[88]

“I think that what Mr. Pearce is saying is that in a tolerant society you have room for free speech, and he is saying that if you curtail that principle you strike at the very principle of tolerance itself and ultimately you undermine a multicultural society.”

Pearce went on to explain that there were only “two very discrete and small categories of conduct” which the bill proscribed that were not already proscribed by other laws: “hate speech” and “giving offense or insulting someone”. He insisted:[89]

“There is simply no evidence that I have seen which demonstrates that conduct of that kind in Australia in 1995 threatens social order.”

I had asked for definitions; Pearce had asked for evidence; neither of us had been satisfied in this hearing. I was allowed the final say by the chairman who kindly thanked me for ‘a very good contribution this afternoon’. I said:[90]

“Could I say something about the matter of conciliation which was raised? […] It was suggested that the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission conciliators are neutral. I think that that is a questionable statement. I think that, in the social-political context in which that body was set up, and in which it operates, an individual Australian citizen may well be entitled not to have confidence that such neutrality exists. I would ask every senator who is present here… [“And who is a white Aryan Australian –”, Leibler sneeringly interrupted…] I would like to ask every senator here to see what I have had to say about that in my short 9-page letter of late January because I made a very serious comment for the senators about just this matter of conciliation.”

Why did one of Australia’s most prominent and powerful Jewish leaders feel a need twice to try to undermine my remarks by associating me, without any justification from my words, with Nazism and Hitler? I left the hearing strengthened in my conviction that Jewish will was a prime motivation behind the bill and that it was not at all benign towards those who would oppose it, no matter how decent they were as people, no matter how eloquent and logical they were in argument. I also felt that I had witnessed an all-too-typical timidity in others when confronted by manifestations of that will.

XI

Three cases brought under the Racial Discrimination Act in its new form which became applicable in October 1995 (without including criminal sanctions for persons found guilty of inciting racial hatred, since the Australian Parliament had rejected that) aroused concern among supporters of free speech. In each case the defendant was found to have transgressed the Act and was accordingly punished. Two were bankrupted by lengthy legal processes which they had to some extent themselves initiated; these were Olga Scully, a Tasmanian woman of Russian ethnicity, and Dr. Fredrick Töben, a Victorian of German origins. The third defendant was a gun journalist from Melbourne’s mass circulation newspaper, the Herald Sun, Andrew Bolt, of Dutch ethnicity; and his case became a cause célèbre. Indeed it is widely understood that the verdict in Bolt’s case was what prompted Tony Abbott to promise reform of the Act in 2012 and to attempt this, unsuccessfully as it has turned out, after he became prime minister.

It appears that Scully had been making a practice of dropping unsolicited political pamphlets and videos in letter-boxes, as well as selling these and various books in a public marketplace. The record of proceedings states that some of these materials claimed that Germany did not engage in organized brutality during World War Two, and that Germans had been wrongly depicted as fiends. It was argued that the bodies of concentration camp victims were not burnt in gas ovens, but had ordinary cremation. The camp at Auschwitz had a swimming pool, school and theatre.[91]

It was also reported that Scully had distributed pamphlets alleging that the Holocaust was a lie, the Talmud encouraged pedophilia, Jews orchestrated the Port Arthur massacre[92], communism was a Jewish plot and the world banks, media and pornography are under Jewish control.

Some of the material she placed in Launceston letter-boxes included The Inadvertent Confession of a Jew, The Jewish Khazar Kingdom, Russian Jews Control Pornography, The Most Debated Question of our Time – Was There Really a Holocaust?, and an untitled excerpt on which was written in longhand:

“The white Christian nations are the true seed of Israel. ‘The synagogue of Satan’ – who say they are Judean – but are lying frauds, are trying to force the white race to mongrelize.”

There was also a document entitled “MFP – What Are Japan’s Motives?”, in which Scully had underlined the names of three individuals mentioned in the article, including that of Mr. David Rockefeller of Chase Manhattan Bank, and written in the margin next to their names “3 Jews”. On a photograph of Rockefeller she had written “Jew” across his forehead.[93]

Mr. Anthony Cavanough QC, the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity commissioner, gave his decision on 21st September 2000. He found that Scully had breached Section 18C of the Act. Factors that contributed to his finding included the “stridently anti-Semitic” tone of her material and “the inflammatory tone of the publications.” He rejected a claim by Scully that she made a clear distinction between “Talmudic/Zionist/Communist Jews” and “good” Jews, pointing out that her leaflets for the most part made no such distinction, but attacked Jews generally.

Justice Cavanough explained why he did not believe that the exemptions allowed in Section 18D (which Scully had, in any case, failed to invoke) would have exonerated her. He felt that the leaflets did not bear “on their face the appearance of reasonableness, good faith and genuineness of purpose.” Rather, they appeared to be “intended to defame and injure Jews”, whether or not they had other purposes. He believed that “the extreme nature of the imputations made, the intemperate and inflammatory tone of the leaflets and the great variety of subject matter which have been made vehicles for the imputations against Jews” combined “to suggest a lack of the reasonableness and good faith required by Section 18D… and a lack of the requisite ‘genuineness’ of purpose.”

The judge further explained that he did not think the exemption of “in good faith” could have been successfully invoked by Scully just because she “honestly or sincerely” held her negative views about Jews.

As for the criterion of “reasonableness,” he felt she would not have succeeded with this either, as her material was “unverified and lacking in persuasiveness.” He evidently did not feel that Scully had taken care prior to publication to establish the truth of the assertions in the pamphlets, or checked them for accuracy, or that she possessed any “special knowledge” which would justify publication. Moreover, he did not believe that her activities were carried out for any “genuine academic, artistic or scientific purpose” (another criterion for exemption). Rather, he saw them as the spreading of “hate propaganda”. He did not regard the leaflets as “reports” or as touching on “a subject of public interest”, since their topics as a whole were too broad to fit the statutory concept. A “subject of public interest could not be some general abstraction unrelated to the conduct of particular individuals.” Finally, the judge did not regard the publications as “comment”, let alone “fair comment.”[94]

It is worth noting at this point some of the definitions contained in the “Guide to the Racial Hatred Act” published by the Australian Human Rights Commission on its website. The phrase “in good faith” is stated to mean that “the act [of publication] must have been done without spite, ill-will or any other improper motive”. If there has been “a culpably reckless and callous indifference” to injury that a targeted person or group would be likely to experience, this also would establish a lack of good faith. Moreover, if publication was found to be “unpersuasive” and having “a main purpose to humiliate and denigrate” a person or group, the exemption would also not excuse it.

The AHRC claims that the test for “done reasonably” is objective:

“Whether or not the publisher […] thought the act was reasonable, it is the ordinary person whose assessment is relevant. The context of the act or publication, community standards of morality and ethics and the impact on the community, on the targeted person or group and on race relations are all relevant.”

What is one to make of the significance of the Scully case? Was justice done? In my judgment Scully, despite her obviously genuine desire to witness to the truth and defend those she felt had been unfairly traduced, was considerably at fault. It seems to me that she had become fanatically obsessed with her political views, so that she relied on writings of unworthy quality, lost to some extent her sense of the humanity of those she was criticizing, lost the crucial awareness that there might be another side to the matter, lost the awareness that she herself might be in error to some extent, and failed to realize that dropping unsolicited material into letter-boxes is an invasion of privacy that is to be avoided if possible.

Her Jewish adversaries had grounds for complaint. Whether they were wise and compassionate in proceeding is a different issue. It is hard to believe that Scully’s activities constituted any seriously dangerous threat to the Jewish community. Perhaps it would have been nobler to ignore this case of a loner with “a bee in her bonnet.” Certainly her punishment of bankruptcy is excessive, but she partly brought this on herself by stubbornness and mismanagement of her case.

What is perhaps most important is the inevitable subjectivity that entered the judging of her case. The language of the Act itself is inevitably vague, ambiguous and capable of different interpretations by different observers. Some of Justice Cavanough’s opinions appear contestable. While there was error and crudity in some of Scully’s publications, there appears also to have been some truth in them, possibly dissident truth that deserves dissemination; and there is a danger that successful litigation in such a case has the effect of “throwing out the baby with the bath water.”

XII

A more important, more sensational and better known case brought under the Racial Discrimination Act was that initiated against Dr. Fredrick Töben by Jeremy Jones and the committee members of the Executive Council of Australian Jewry in 1996, a matter that was to drag out until 2009. Töben had established a revisionist website under the name of the Adelaide Institute. The complaint was that Töben through his website had engaged in malicious anti-Jewish propaganda. He had denied the Nazi genocide of the Jews and blamed Jews for the crimes committed under Stalin. He had stated:[95]