Tell-tale documents and photos from Auschwitz

Jean-Claude Pressac’s book, Auschwitz: Technique and Operation of the Gas Chambers, is the first serious and detailed response to the revisionist critique of the generally accepted Auschwitz extermination story. This 564-page work is itself evidence that Holocaust Revisionism can no longer be dismissed as a temporary or frivolous phenomenon, but is a formidable challenge that must be taken seriously.

As Robert Faurisson and Mark Weber have pointed out in their reviews of his book, Pressac fails to prove his case. But in his ultimately unsuccessful effort to shore up the crumbling “exterminationist” view, Pressac is obliged to make many highly significant concessions to the revisionist position. Both explicitly and implicitly, he discredits countless Holocaust claims, “testimonies” and interpretations.

His book features hundreds of valuable illustrations, including many good-quality reproductions of previously unpublished original diagrams and documents that simply cannot be reconciled with the generally accepted Holocaust extermination story. Reproduced on the following pages are a few of these illustrations, which were selected from Pressac’s book by Mark Weber, who also provided the captions. (See also Weber’s review of Pressac’s book in the summer 1990 Journal of Historical Review.)

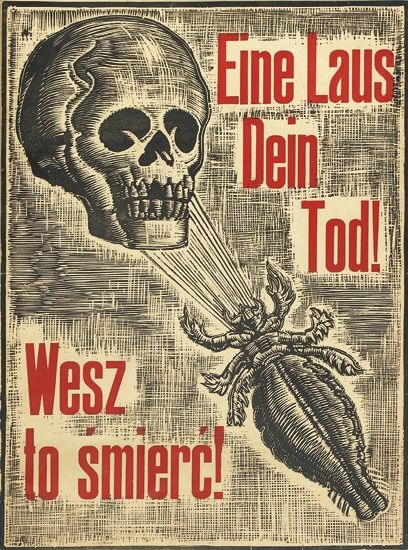

“One Louse, Your Death!” This bilingual (German-Polish) poster graphically warned Auschwitz inmates of the danger of typhus bearing lice. (p. 54) Other measures taken by camp authorities to combat typhus included camp quarantines, routine delousings of barracks and clothes with “Zyklon” gas, quarantine of newly arriving prisoners, disinfection baths for inmates, and inspections of barracks. The dread disease claimed the lives of many tens of thousands of inmates. German camp personnel also fell victim, including SS garrison physician Dr. Siegfried Schwela and other high-level SS officers.

““Zyklon”” (hydrocyanic acid gas), a widely available commercial insecticide and rodent killer, was used extensively at Auschwitz to kill typhus-bearing lice. It was used, for example, to fumigate clothes in delousing gas chambers, and to kill vermin in barracks and other buildings.

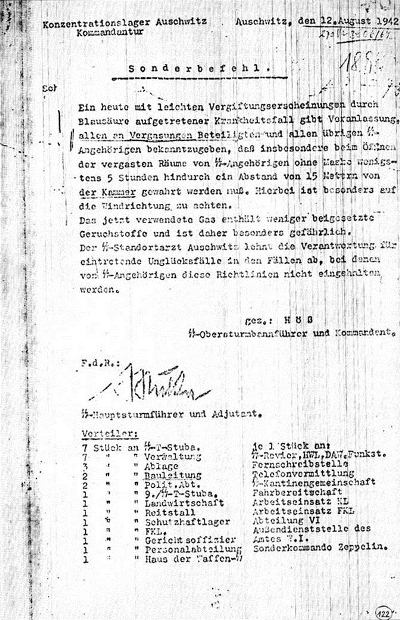

Commandant Rudolf Höss emphasized its deadliness when not used properly in this “special order” of August 12, 1942. (p. 201) Forty copies were distributed to officials throughout the camp. Höss warned:

Today there was a case of illness due to slight symptoms of poisoning with Prussic acid [Zyklon]. This makes it necessary to warn all those involved with gassings, as well as all other SS personnel, that especially when opening gassed rooms, SS personnel not wearing gas masks must wait at least five hours and keep a distance of 15 meters from the chamber. In this regard, particular attention should be paid to the wind direction.

The gas now being used contains less [protective] odor additive, and is therefore especially dangerous.

The SS garrison physician refuses to accept responsibility for accidents that may occur in cases where SS personnel do not obey these guidelines.

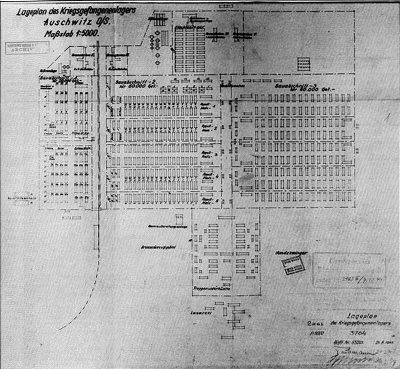

Shown on this March 1944 Auschwitz construction department diagram of the Birkenau camp are crematory buildings II and III (at upper left), and IV and V (at upper center). Between them is the “Disinfection and disinfestation facility” (“Desinfektions u. Entwesungsanlage”), which was also known as the “Central Sauna” (“Zentralsauna”). (p. 514.)

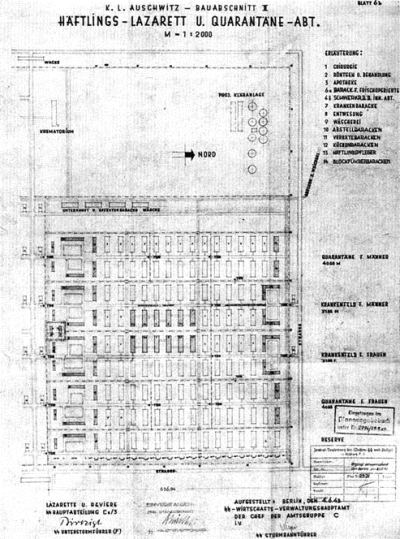

This August 1942 architectural diagram of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp, supposedly the Third Reich’s main “extermination” center, shows that German authorities planned to enlarge the camp so that it would eventually hold 200,000 inmates. (p. 203) The “Mexiko” section at the top, which would hold 60,000 people, was only partially completed, and the comparable section at the bottom was never begun. This document cannot be reconciled with the camp’s alleged function as a top secret extermination center.

At no time were any of Auschwitz-Birkenau’s four crematory buildings ever hidden, concealed or “camouflaged.” They were in plain view, and even newly arriving Jews could easily see them. Crematory buildings II and III were particularly visible. In this photograph, taken in May or June 1944, crematory building (Krema) III can be plainly seen in the background. (p. 251) In the foreground are Jews who have just arrived at Birkenau from Hungary.

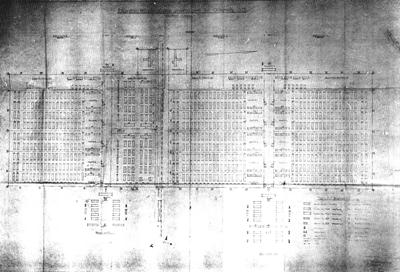

Auschwitz-Birkenau was greatly enlarged in 1943 and 1944 to accommodate the arrival of more and more Jews. Accordingly, plans were made for more extensive hospital and quarantine facilities.

This plan for a new “Prisoner hospital and quarantine section” (“Häftlings-Lazarett u. Quarantäne-Abt.”) in the Birkenau camp’s “Mexiko” section was prepared in June 1943 by the WVHA agency in Berlin that administered the concentration camp system. It was quickly approved by the Auschwitz camp construction department. This “hospital and quarantine” section for 16,596 inmates included surgery, x-ray, delousing, and laundry facilities, as well as barracks for severely ill inmates.

Pressac acknowledges (p. 512) the difficulty of reconciling these plans with the camp’s alleged function as an extermination facility:

There is incompatibility in the creation of a health camp a few hundred yards from four Krematorien [crematory facilities] where, according to official history, people were exterminated on a large scale … It is obvious that KGL [concentration camp] Birkenau cannot have had at one and the same time two opposing functions: health care and extermination. The plan for building a very large hospital section in BA III [“Mexiko” section of Birkenau] thus shows that the Krematorien [facilities] were built purely for incineration, without any homicidal gassings, because the SS wanted to “maintain” its concentration camp labor force.

The “Mexiko” section was only partially completed and “became a transit camp in May–June 1944 for the Hungarian transports,” Pressac reports.

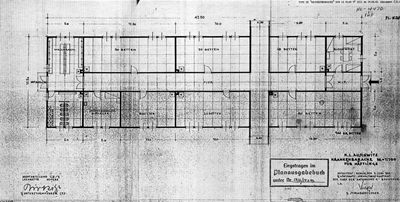

Architectural diagram of an Auschwitz “barracks for sick inmates.” (p. 513) The barracks has 144 beds, large wash and toilet rooms, and a room for medical staff. (This June 1943 diagram is also Nuremberg document NO-4470.) Photos of hospital facilities for inmates are also reproduced in Pressac’s book. (pp. 510–511)

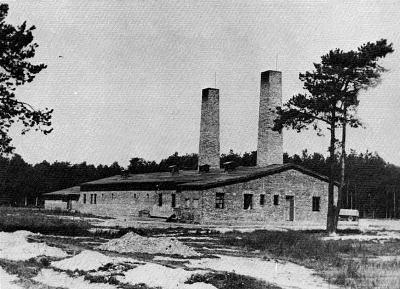

Auschwitz-Birkenau crematory building (Krema) IV shortly after its completion in late March 1943. (p. 418) This building, supposedly one of the principal extermination gassing centers, was actually built very hastily in response to the terrible typhus epidemic that raged during the summer of 1942. (pp. 392, 398) This facility was so quickly and so poorly constructed that it could be used only intermittently for a short time, and was shut down for good in May 1943. (pp. 413, 420)

Were thousands of Jews murdered here? This is the inside of the alleged extermination gas chamber in the Auschwitz I main camp. (p. 155) German camp authorities never bothered to obliterate the incriminating “evidence” by destroying this structure. As Pressac acknowledges in his book (pp. 123, 133), there is no hard evidence that this room was ever an extermination facility.

Not long after the Allied liberation of Auschwitz in January 1945, Soviet and Polish officials organized a dance on the roof of the supposed extermination gas chamber in the main camp. Apparently they did not regard it as a mass extermination facility. In his book about Auschwitz (p. 149), Pressac expresses astonishment and regret over this incident:

Above the stage, dominated by a red star with the hammer and sickle, fly the flags of Poland (left) and the Soviet Union (right), with lamps mounted above them. This photograph proves that a dance was organized in 1945 on the roof of Krematorium I, and that people actually danced above the homicidal gas chamber. This episode appears almost unbelievable and sadly regrettable today, and the motives for it are not known. This photo also proves that the present covering of roofing felt and zinc surround [sic] of the roof are not original.

Eating hall for inmates at the Auschwitz III (Monowitz) camp. (p. 506) Inmates from Birkenau and the rest of the camp complex were routinely transferred to and from Monowitz, which hardly makes sense if Auschwitz had been an extermination center.

Ukrainian women’s choir at the Auschwitz III (Monowitz) camp. (p. 506) A surprisingly wide range of free-time activities, including entertainment, was available to forced-labor inmates.

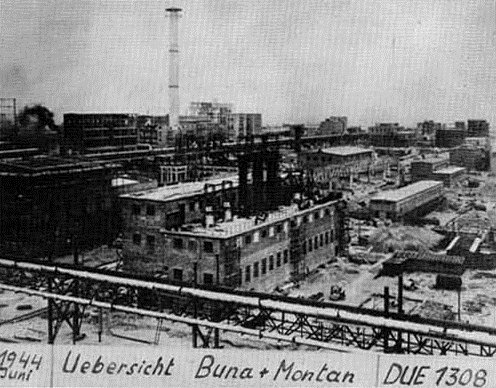

Partial overview of the extensive “Buna” industrial works at Auschwitz III (Monowitz) camp, where gasoline was produced from coal. (p. 506). This photo, as well as the two previous ones, are from the Duerrfeld document file in the National Archives (Washington, DC).

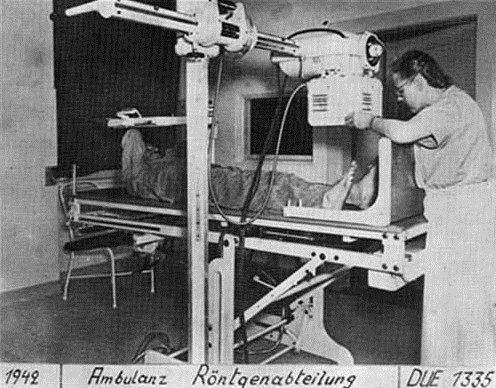

[This image is taken from the same page of Pressac's book as the three previous ones, showing the X-ray room at the Auschwitz inmate hospital; ed.]

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 11, no. 1 (spring 1991), pp. 67-80

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a